Interfaith dialogue refers to cooperative, constructive, and positive interaction between people of different religious traditions (i.e. "faiths") and/or spiritual or humanistic beliefs, at both the individual and institutional levels. It is distinct from syncretism or alternative religion, in that dialogue often involves promoting understanding between different religions or beliefs to increase acceptance of others, rather than to synthesize new beliefs.

The Archdiocese of Chicago's Office for Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs defines "the difference between ecumenical, interfaith, and interreligious relations", as follows:

- "ecumenical" as "relations and prayer with other Christians",

- "interfaith" as "relations with members of the 'Abrahamic faiths' (Jewish, Muslim and Christian traditions)," and

- "interreligious" as "relations with other religions, such as Hinduism and Buddhism".

Some interfaith dialogues have more recently adopted the name interbelief dialogue, while other proponents have proposed the term interpath dialogue, to avoid implicitly excluding atheists, agnostics, humanists, and others with no religious faith but with ethical or philosophical beliefs, as well as to be more accurate concerning many world religions that do not place the same emphasis on "faith" as do some Western religions. Similarly, pluralistic rationalist groups have hosted public reasoning dialogues to transcend all worldviews (whether religious, cultural or political), termed transbelief dialogue. To some, the term interreligious dialogue has the same meaning as interfaith dialogue. Neither are the same as nondenominational Christianity. The World Council of Churches states: “Following the lead of the Roman Catholic Church, other churches and Christian religious organizations, such as the World Council of Churches, have increasingly opted to use the word interreligious rather than interfaith to describe their own bilateral and multilateral dialogue and engagement with other religions. [...] the term interreligious is preferred because we are referring explicitly to dialogue with those professing religions – who identify themselves explicitly with a religious tradition and whose work has a specific religious affiliation and is based on religious foundations."

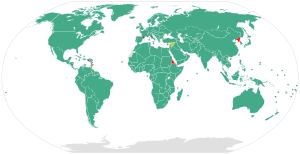

Throughout the world there are local, regional, national and international interfaith initiatives; many are formally or informally linked and constitute larger networks or federations. The often quoted "There will be no peace among the nations without peace among the religions. There will be no peace among the religions without dialogue among the religions" was formulated by Hans Küng, a Professor of Ecumenical Theology and President of the Global Ethic Foundation. Interfaith dialogue forms a major role in the study of religion and peacebuilding.

History

Christians, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, Jews, Baháʼís, Eckists, Sikhs, Jains, Wiccans, Unitarian Universalists, Shintoists, Taoists, Thelemites, Tenrikyoists, Zoroastrians

History records examples of interfaith initiatives throughout the ages, with varying levels of success in establishing one of three types of "dialogue" to engender, as recently described, either understanding, teamwork, or tolerance:

- "In the dialogue of the head, we mentally reach out to the other to learn from those who think differently from us."

- "In the dialogue of the hands, we all work together to make the world a better place in which we must all live together."

- "In the dialogue of the heart, we share the experience of the emotions of those different from us."

The historical effectiveness of interfaith dialogue is an issue of debate. Friar James L. Heft, in a lecture on "The Necessity of Inter-Faith Diplomacy," spoke about the conflicts among practitioners of the three Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity and Islam). Noting that except for the Convivencia in the 14th and 15th centuries, believers in these religions have either kept their distance or have been in conflict, Heft maintains, "there has been very little genuine dialogue" between them. "The sad reality has been that most of the time Jews, Muslims and Christians have remained ignorant about each other, or worse, especially in the case of Christians and Muslims, attacked each other."

In contrast, The Pluralism Project at Harvard University says, "Every religious tradition has grown through the ages in dialogue and historical interaction with others. Christians, Jews, and Muslims have been part of one another's histories, have shared not only villages and cities, but ideas of God and divine revelation."

The importance of Abrahamic interfaith dialogue in the present has been bluntly presented: "We human beings today face a stark choice: dialogue or death!"

More broadly, interfaith dialogue and action have occurred over many centuries:

- In the 16th century, the Emperor Akbar encouraged tolerance in Mughal India, a diverse nation with people of various faith backgrounds, including Islam, Hinduism, Sikhism, and Christianity.

- Religious pluralism can also be observed in other historical contexts, including Muslim Spain. Zarmanochegas (Zarmarus) (Ζαρμανοχηγὰς) was a monk of the Sramana tradition (possibly, but not necessarily a Buddhist) from India who journeyed to Antioch and Athens while Augustus (died 14 CE) was ruling the Roman Emprire.

- "Disputation of Barcelona – religious disputation between Jews and Christians in 1263. The apostate Paulus [Pablo] Christiani proposed to King James I of Aragon that a formal public religious disputation on the fundamentals of faith should be held between him and R. Moses b. Nahman (Nachmanides) whom he had already encountered in Gerona. The disputation took place with the support of the ecclesiastical authorities and the generals of the Dominican and Franciscan orders, while the king presided over a number of sessions and took an active part in the disputation. The Dominicans Raymond de Peñaforte, Raymond Martini, and Arnold de Segarra, and the general of the Franciscan order in the kingdom, Peter de Janua, were among the Christian disputants. The single representative for the Jewish side was Naḥmanides. The four sessions of the disputation took place on July 20, 27, 30, and 31, 1263 (according to another calculation, July 20, 23, 26, and 27). Naḥmanides was guaranteed complete freedom of speech in the debate; he took full advantage of the opportunity thus afforded and spoke with remarkable frankness. Two accounts of the disputation, one in Hebrew written by Naḥmanides and a shorter one in Latin, are the main sources for the history of this important episode in Judeo-Christian polemics. According to both sources the initiative for the disputation and its agenda were imposed by the Christian side, although the Hebrew account tries to suggest a greater involvement of Naḥmanides in finalizing the items to be discussed. When the ecclesiastics who saw the "not right" turn the disputation was taking, due to Nahmanides persuasive argumentation, they urged that it should be ended as speedily as possible. It was, therefore, never formally concluded, but interrupted. According to the Latin record of the proceedings, the disputation ended because Nahmanides fled prematurely from the city. In fact, however, he stayed on in Barcelona for over a week after the disputation had been suspended in order to be present in the synagogue on the following Sabbath when a conversionist sermon was to be delivered. The king himself attended the synagogue and gave an address, an event without medieval precedent. Nahmanides was permitted to reply on this occasion. The following day, after receipt of a gift of 300 sólidos from the king, he returned home."

- "While the Disputation may have been a great achievement for Paulus Christiani in his innovative use of rabbinic sources in Christian missionary efforts, for Naḥmanides it represented an additional example of the wise and courageous leadership which he offered his people."

19th-century initiatives

- The 1893 Parliament of World Religions at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois is "often regarded as the birth of the interfaith movement". The congress was the first organized, international gathering of religious leaders. Since its first meeting in 1893, there have been eight meetings including one in 2015.

20th-century initiatives

- In 1900, the International Association for Religious Freedom (IARF) was founded under a name different from its current one. In 1987, its statement of purpose was revised to include advancing "understanding, dialogue and readiness to learn and promotes sympathy and harmony among the different religious traditions". In 1990, its membership was enlarged "to include all the world's major religious groups". In 1996, IARF's World Congress included representatives of Palestinian and Israeli IARF groups and Muslim participants made presentations.

- In December 1914, just after World War I began, a group of Christians gathered in Cambridge, England to found the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) "in hopes of bringing people of faith together to promote peace, and it went on to become a leading interfaith voice for non-violence and non-discrimination". It has branches and affiliated groups in over 50 countries on every continent. The membership includes "Jews, Christians, Buddhists, Muslims, Indigenous religious practitioners, Baháʼí, and people of other faith traditions, as well as those with no formal religious affiliation".

- In 1936, the World Congress of Faiths (WCF) formed in London. It is "one of the oldest interfaith bodies in the world". One of its purposes is to bring "people of faith together to enrich their understandings of their own and others' traditions". It does this by offering opportunities "to meet, explore, challenge and understand different faith traditions through events from small workshops to large conferences, partnership working, online conversation, and publications".

- In 1949, following the devastation of World War II, the Fellowship In Prayer was founded in 1949 by Carl Allison Evans and Kathryn Brown. Evans believed that unified prayer would "bridge theological or structural religious differences," would "open the mind and heart of the prayer to a new understanding of and appreciation for the beliefs and values of those following different spiritual paths," and would "advance interfaith understanding and mutual respect among religious traditions,"

- In 1952, the International Humanist and Ethical Union (IHEU) was founded in Amsterdam. It serves as "the sole world umbrella organisation embracing Humanist, atheist, rationalist, secularist, skeptic, laique, ethical cultural, freethought and similar organisations world-wide". IHEU's "vision is a Humanist world; a world in which human rights are respected and everyone is able to live a life of dignity". It implements its vision by seeking "to influence international policy through representation and information, to build the humanist network, and let the world know about the worldview of Humanism".

- In 1958, the Center for the Study of World Religions (CSWR) at Harvard Divinity School (HDS) began. Since then, it "has been at the forefront of promoting the sympathetic study and understanding of world religions. It has supported academic inquiry and international understanding in this field through its residential community," and "its research efforts and funding, and its public programs and publications".

- In 1960, Juliet Hollister (1916–2000) created the Temple of Understanding (TOU) to provide "interfaith education" with the purpose of "breaking down prejudicial boundaries". The Temple of Understanding "over several years hosted meetings that paved the way for the North American Interfaith Network (NAIN)".

- In the late 1960s, interfaith groups such as the Clergy And Laity Concerned (CALC) joined around Civil Rights issues for African-Americans and later were often vocal in their opposition to the Vietnam War.

- In 1965, "about 100 Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish clergy" formed Clergy Concerned about Vietnam (CCAV). Its purpose was "to challenge U.S. policy on Vietnam". When the group admitted laity, it renamed itself National Emergency Committee of Clergy and Laymen Concerned about Vietnam (CALCAV) In 1967, Martin Luther King Jr. used its platform for his "Beyond Vietnam" speech. Later, CALCAV addressed other issues of social justice issues and changed its name to become simply Clergy and Laymen Concerned (CALC).

- In 1965, during Vatican II, it was decided that relations with all religions should be developed. To do this, Pope Paul VI established a special secretariat (later a pontifical council) for relationships with non-Christians. The papal encyclical Ecclesiam Suam emphasized the importance of positive encounter between Christians and people of other faith traditions. The Declaration on the Relationship of the Church to Non-Christian Religions (Nostra Aetate) of 1965, spelled out the pastoral dimensions of this relationship.

- In 1967, the World Council of Churches conference "proved to be a landmark both as the beginning of serious interest in interfaith dialogue as such in the WCC, and as the first involvement in the ecumenical discussion of the Vatican Secretariat for Non-Christians".

- In 1970, the first World Conference of Religions for Peace was held in Kyoto, Japan. Religions for Peace is "the world's largest and most representative multi-religious coalition advancing common action for peace". Its work includes "dialogue" that "bears fruit in common concrete action". Through the organization, diverse religious communities discern "deeply held and widely shared" moral concerns, such as, "transforming violent conflict, promoting just and harmonious societies, advancing human development and protecting the earth".

- In 1978, the Interfaith Conference of Metropolitan Washington (IFC) was formed. "The IFC brings together eleven historic faith communities to promote dialogue, understanding and a sense of community and to work cooperatively for justice throughout the District of Columbia region." Members include the Baháʼí Faith, Buddhist, Hindu, Islamic, Jain, Jewish, Latter-day Saints, Protestant, Roman Catholic, Sikh and Zoroastrian faith communities.

- In 1981, Minhaj-ul-Quran was founded. It is "a Pakistan-based international organization working to promote peace, tolerance, interfaith harmony and education, tackle extremism and terrorism, engage with young Muslims for religious moderation, promote women's rights, development and empowerment, and provide social welfare and promotion of human rights". Minhaj-ul-Quran offers free download of books.

- On October 27, 1986 Pope John Paul II had a day of prayer at Assisi and invited "about fifty Christians and fifty leaders of other faiths". In his book One Christ–Many Religions, S. J. Samartha says that the importance of that day of prayer for "interreligious relationships cannot be overestimated" and gives "several reasons" for its importance:

- "It conferred legitimacy to Christian initiatives in interreligious dialogues."

- "It was seen as an event of theological significance."

- "Assisi was recognized as an act of dialogue in the highest degree."

- "It emphasized the religious nature of peace."

- However, Samartha added, two points caused "disquiet" to people of faiths other than Christian:

- The Pope's insistence on Christ as the only source of peace.

- For the prayers Christians were taken to one place and people of other faiths to another place.

- Besides, the disquiet caused by the Pope's day of prayer, there is an ongoing "suspicion" by "neighbors of other faiths" that "dialogues may be used for purposes of Christian mission".

- In 1991, Harvard University's Diana L. Eck launched the Pluralism Project by teaching a course on "World Religions in New England," in which students explored the "diverse religious communities in the Boston area". This project was expanded to charting "the development of interfaith efforts throughout the United States" and then the world. The Pluralism Project posts the information on the Pluralism Project website.

- In 1993, on the centennial of its first conference, the Council for a Parliament of the World's Religions hosted a conference in Chicago with 8,000 participants from faith backgrounds around the world. "The Parliament is the oldest, the largest, and the most inclusive gathering of people of all faith and traditions." The organization hosts meetings around the world every few years. Its 2015 conference decided to hold meetings every two years.

- In 1994, the Interfaith Alliance was created "to celebrate religious freedom and to challenge the bigotry and hatred arising from religious and political extremism infiltrating American politics". As of 2016, the Interfaith Alliance has 185,000 members across the country made up of 75 faith traditions as well as those of no faith tradition. The Interfaith Alliance works to (1) "respect the inherent rights of all individuals–as well as their differences", (2) "promote policies that protect vital boundaries between religion and government", and (3) "unite diverse voices to challenge extremism and build common ground".

- In 1995, the Interfaith Center at the Presidio was founded with "a multi-faith Board". The Center is a San Francisco Bay Area "interfaith friendship-building" that welcomes "people of all faiths". The Center is committed to "healing and peacemaking within, between, and among religious and spiritual traditions".

- In 1996, the Center for Interfaith Relations in Louisville, Kentucky established the Festival of Faiths, a multi-day event that promotes interfaith understanding, cooperation and action.

- In 1996, Kim Bobo founded the Interfaith Worker Justice (IWJ) organization. Today IWJ includes a national network of more than 70 local interfaith groups, worker centers and student groups, making it the leading national organization working to strengthen the religious community's involvement in issues of workplace justice.

- In 1997, the Interfaith Center of New York (ICNY) was founded by the Very Rev. James Parks Morton, former Dean of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. ICNY's historic partners have included the New York State Unified Court System, Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of New York, UJA-Federation of New York, the Center for Court Innovation, the Harlem Community Justice Center, CONNECT and the city's nine Social Work Schools. ICNY works with hundreds of grassroots and immigrant religious leaders from fifteen different faith and ethnic traditions. Its "long-term goal is to help New York City become a nationally and internationally-recognized model for mutual understanding and cooperation among faith traditions".

- In 1998, the Muslim Christian Dialogue Forum was formed "to promote religious tolerance between Muslims and Christians so that they could work for the promotion of peace, human rights, and democracy". On December 8, 2015, the Forum sponsored a seminar on the subject of "Peace on Earth" at the Forman Christian College. The purpose was to bring the Muslim and Christian communities together to defeat "terrorism and extremism".

- In 1998, Interfaith Power & Light (IPL) began as a project of the Episcopal Church's Grace Cathedral, San Francisco, California. Building on its initial success, the IPL model has "been adopted by 40 state affiliates", and IPL is "working to establish Interfaith Power & Light programs in every state". Ecological sustainability is central to IPL's "faith-based activism". The organization's work is reported in its Fact Sheet and 1915 Annual Report.

- In 1999, The Rumi Forum (RF) was founded by the Turkish Hizmet [Service to Humanity] Movement. RF's mission is "to foster intercultural dialogue, stimulate thinking and exchange of opinions on supporting and fostering democracy and peace and to provide a common platform for education and information exchange". In particular, the Forum is interested in "pluralism, peace building and conflict resolution, intercultural and interfaith dialogue, social harmony and justice, civil rights and community cohesion".

21st-century initiatives

- In 2000, the United Religions Initiative (URI) was founded "to promote enduring, daily interfaith cooperation, to end religiously motivated violence and to create cultures of peace, justice and healing for the Earth and all living beings". It now claims "more than 790 member groups and organizations, called Cooperation Circles, to engage in community action such as conflict resolution and reconciliation, environmental sustainability, education, women's and youth programs, and advocacy for human rights".

- In 2001, after the September 11 attacks, "interfaith relations proliferated". "Conversations about the urgency of interfaith dialogue and the need to be knowledgeable about the faith of others gained traction in new ways."

- In 2001, the Children of Abraham Institute ("CHAI") was founded "to articulate the 'hermeneutics of peace' ... that might be applied to bringing Jewish, Muslim, and Christian religious, social, and political leaders into shared study not only of the texts of Scripture but also of the paths and actions of peace that those texts demand".

- In 2001, the Interfaith Encounter Association (IEA) was established in Israel. Its impetus dates from the late 1950s in Israel when a group of visionaries (which included Martin Buber) recognised the need for interfaith dialogue. IEA is dedicated to promoting "coexistence in the Middle East through cross-cultural study and inter-religious dialogue". It forms and maintains "on-going interfaith encounter groups, or centers, that bring together neighboring communities across the country. Each center is led by an interfaith coordinating team with one person for each community in the area."

- In 2002 the Messiah Foundation International was formed as "an interfaith, non-religious, spiritual organisation". The organisation comprises "people belonging to various religions and faiths" who "strive to bring about widespread divine love and global peace".

- In 2002, the World Council of Religious Leaders (WCRL) was launched in Bangkok. It is "an independent body" that brings religious resources to support the work of the United Nations and its agencies around the world, nation states and other international organizations, in the "quest for peace". It offers "the collective wisdom and resources of the faith traditions toward the resolution of critical global problems". The WCRL is not a part of the United Nations.

- In 2002, Eboo Patel, a Muslim, started the Interfaith Youth Core (IFYC) with a Jewish friend and an evangelical Christian staff worker. The IYYC was started to bring students of different religions "together not just to talk, but to work together to feed the hungry, tutor children or build housing". The IFYC builds religious pluralism by "respect for people's diverse religious and non-religious identities" and "common action for the common good".

- In 2003, the Jordanian Interfaith Coexistence Research Center (JICRC) was founded by The Very Reverend Father Nabil Haddad. It "focuses on grassroots interfaith dialogue and coexistence". JICRC provides "advice to government and non-government organizations and individual decision makers regarding questions of inter-religious understanding" and "participates in interfaith efforts on the local, regional, and international levels".

- In 2006, the Coexist Foundation was established. Its mission is "to advance social cohesion through education and innovation" and "to strengthen the bond that holds a society together through a sustainable model of people working and learning together" in order to reduce "prejudice, hate and violence".

- In 2007, the Greater Kansas City Festival of Faiths put on its first festival. The festival's goals include: increased participation in interfaith experience and fostering dialogue. Festivals include dramatic events and speakers to "expand interaction and appreciation for different worldviews and religious traditions" One-third of the attendees are 'first-timers' to any interfaith activity.

- On October 13, 2007 Muslims expanded their message. In A Common Word Between Us and You, 138 Muslim scholars, clerics and intellectuals unanimously came together for the first time since the days of the Prophet[s] to declare the common ground between Christianity and Islam.

- In 2007, the biennial interfaith Insight Film Festival began. It encourages "filmmakers throughout the world to make films about 'faith'". The Festival invites "participants from all faith backgrounds" as a way contributing "to understanding, respect and community cohesion".

- In 2008, Rabbi Shlomo Riskin established the Center for Jewish-Christian Understanding and Cooperation (CJCUC). The center was founded to "begin a theological dialogue" between Jews and Christians with the belief that in dialogue the two faiths will "find far more which unites" them than divides them. The center, currently located at the Bible Lands Museum in Jerusalem, engages in Hebraic Bible Study for Christians, from both the local community and from abroad, has organized numerous interfaith praise initiatives, such as Day to Praise, and has established many fund-raising initiatives such as Blessing Bethlehem which aim to aid the persecuted Christian community of Bethlehem, in part, and the larger persecuted Christian community of the Middle East region and throughout the world.

- In 2008, through the collaboration of the Hebrew Union College, Omar Ibn Al-Khattab Foundation, and the University of Southern California, the Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement was created. The Center was "inspired by USC President Steven B. Sample's vision of increasing collaboration between neighboring institutions in order to benefit both the university and the surrounding community". Its mission is "to promote dialogue, understanding and grassroots, congregational and academic partnerships among the oldest and the newest of the Abrahamic faiths while generating a contemporary understanding in this understudied area and creating new tools for interfaith communities locally, nationally and beyond."

- July 2008 – A historic interfaith dialogue conference was initiated by King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia to solve world problems through concord instead of conflict. The conference was attended by religious leaders of different faiths such as Christianity, Judaism, Buddhism, Hinduism, and Taoism and was hosted by King Juan Carlos of Spain in Madrid.

- January 2009, at Gujarat's Mahuva, the Dalai Lama inaugurated an interfaith "World Religions-Dialogue and Symphony" conference convened by Hindu preacher Morari Bapu from January 6 to 11, 2009. This conference explored ways and means to deal with the discord among major religions, according to Morari Bapu. Participants included Prof. Samdhong Rinpoche on Buddhism, Diwan Saiyad Zainul Abedin Ali Sahib (Ajmer Sharif) on Islam, Dr. Prabalkant Dutt on non-Catholic Christianity, Swami Jayendra Saraswathi on Hinduism and Dastur Dr. Peshtan Hormazadiar Mirza on Zoroastrianism.

- In 2009, the Vancouver School of Theology opened the Iona Pacific Inter-religious Centre. The Centre "models dialogical, constructive, and innovative research, learning and social engagement". The Centre operates under the leadership of Principal and Dean, Dr. Wendy Fletcher, and Director, Rabbi Dr. Robert Daum.

- In 2009, the Charter for Compassion was unveiled to the world. The Charter was inspired by Karen Armstrong when she received the 2008 TED Prize. She made a wish that the TED community would "help create, launch, and propagate a Charter for Compassion". After the contribution of thousands of people the Charter was compiled and presented. Charter for Compassion International serves as "an umbrella for people to engage in collaborative partnerships worldwide" by "concrete, practical actions".

- In 2009, Council of Interfaith Communities (CIC) was incorporated in Washington, District of Columbia. It mission was "to be the administrative and ecclesiastical home for independent interfaith/multifaith churches, congregations and seminaries in the USA" and to honor "Interfaith as a spiritual expression". The CIC is one component of the World Council of Interfaith Communities.

- In 2010, Interfaith Partners of South Carolina was formed. It was the first South Carolina statewide diversity interfaith organization.

- In 2010, Project Interfaith began its work. 35 volunteers began recording interviews with people in Omaha, Nebraska. Working in pairs, the volunteers were paired up and given a Flip Video camera to record the interviews. The interviewees were asked three questions: (1) "How do you identify yourself spiritually and why?," (2) "What is a stereotype that impacts you based on your religious and spiritual identity?," and (3) "How welcoming do you find our community for your religious or spiritual path?" The recorded interviews were posted on social media sites, like Facebook, Twitter, Flickr, and YouTube. Project Interfaith terminated in 2015.

- In 2010, the Interfaith Center for Sustainable Development (ICSD) was established. ICSD is the largest interfaith environmental organization in the Middle East. Its work is bringing together "faith groups, religious leaders, and teachers to promote peace and sustainability".

- In 2011, President Obama issued the Interfaith and Community Service Campus Challenge by sending a letter to all presidents of institutions of higher education in the United States. The goals of the Challenge included maximizing "the education contributions of community-based organizations, including faith and interfaith organizations". By 2015, more than 400 institutions of higher education had responded to the Challenge. In the 2015 Annual President's Interfaith and Community Service Campus Challenge Gathering, international participants were hosted for the first time.

- In 2012, the King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz International Centre for Interreligious and Intercultural Dialogue (KAICIID) opened in Vienna, Austria. The board of directors included Jews, Christians, and Muslims. A rabbi on the board said that "the prime purpose is to empower the active work of those in the field, whether in the field of dialogue, of social activism or of conflict resolution". A Muslim member of the board said that "the aim is to promote acceptance of other cultures, moderation and tolerance". According to KAICIID officials, "the center is independent and would not be promoting any one religion".

- In February 2016, the International Partnership on Religion and Sustainable Development (PaRD) was launched at the ‘Partners for Change’ conference in Berlin. The network connects government bodies, faith-based organisations and civil-society agencies from around the world to encourage communication on religion and sustainable development.

- In 2016, the National Catholic Muslim Dialogue (NCMD) was established in the United States. This is a joint venture between the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB), the Islamic Society of North America, the Islamic Circle of North America, Islamic Shura Council of Southern California, and the Islamic Educational Center of Orange County. The NCMD was an outgrowth of longstanding regional dialogues in the United States co-sponsored by the USCCB and their regional partners.

- In February 2017, Sister Lucy Kurien, founder of Maher NGO, founded the Interfaith Association for Service to Humanity and Nature in Pune, India. She defines interfaith spirituality as, "We respect and love all religions. We never put down anyone’s religion, or uphold one religion to the exclusion of others. What we want is to believe and respect interfaith religion, inclusive of all faith traditions. In our community spiritual practices, we invoke our prayers to the Divine, rather than invoking any particular name or form of God to the exclusion of others." As of October 2017, this new community has 198 members from 8 countries.

The United States Institute of Peace published works on interfaith dialogue and peacebuilding including a Special Report on Evaluating Interfaith Dialogue

Religious intolerance persists

The above section recounts a "long history of interfaith dialogue". However, a 2014 article in The Huffington Post

said that "religious intolerance is still a concern that threatens to

undermine the hard work of devoted activists over the decades".

Nevertheless, the article expressed hope that continuing "interfaith

dialogue can change this".

Policies of religions

A PhD thesis Dialogue Between Christians, Jews and Muslims argues that "the paramount need is for barriers against non-defensive dialogue conversations between Christians, Jews, and Muslims to be dismantled to facilitate development of common understandings on matters that are deeply divisive". As of 2012, the thesis says that this has not been done.

Baháʼí Faith

Interfaith and multi-faith interactivity is integral to the teachings of the Baháʼí Faith. Its founder Bahá'u'lláh enjoined his followers to "consort with the followers of all religions in a spirit of friendliness and fellowship". Baháʼís are often at the forefront of local inter-faith activities and efforts. Through the Baháʼí International Community agency, the Baháʼís also participate at a global level in inter-religious dialogue both through and outside of the United Nations processes.

In 2002 the Universal House of Justice, the global governing body of the Baháʼís, issued a letter to the religious leadership of all faiths in which it identified religious prejudice as one of the last remaining "isms" to be overcome, enjoining such leaders to unite in an effort to root out extreme and divisive religious intolerance.

Buddhism

Buddhism has historically been open to other religions. Ven. Dr. K. Sri Dhammananda stated:

"Buddhism is a religion which teaches people to 'live and let live'. In the history of the world, there is no evidence to show that Buddhists have interfered or done any damage to any other religion in any part of the world for the purpose of introducing their religion. Buddhists do not regard the existence of other religions as a hindrance to worldly progress and peace."

The fourteenth century Zen master Gasan Joseki indicated that the Gospels were written by an enlightened being:

- "And why take ye thought for raiment? Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow. They toil not, neither do they spin, and yet I say unto you that even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these... Take therefore no thought for the morrow, for the morrow shall take thought for the things of itself."

- Gasan said: "Whoever uttered those words I consider an enlightened man."

The 14th Dalai Lama has done a great deal of interfaith work throughout his life. He believes that the "common aim of all religions, an aim that everyone must try to find, is to foster tolerance, altruism and love". He met with Pope Paul VI at the Vatican in 1973. He met with Pope John Paul II in 1980 and also later in 1982, 1986, 1988, 1990, and 2003. During 1990, he met in Dharamsala with a delegation of Jewish teachers for an extensive interfaith dialogue. He has since visited Israel three times and met during 2006 with the Chief Rabbi of Israel. In 2006, he met privately with Pope Benedict XVI. He has also met the late Archbishop of Canterbury Dr. Robert Runcie, and other leaders of the Anglican Church in London, Gordon B. Hinckley, late President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons), as well as senior Eastern Orthodox Church, Muslim, Hindu, Jewish, and Sikh officials.

In 2010, the Dalai Lama was joined by Rev. Katharine Jefferts Schori, presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church, Chief Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth, and Islamic scholar Professor Seyyed Hossein Nasr of George Washington University when Emory University's Center for the Study of Law and Religion hosted a "Summit on Happiness".

Christianity

Traditional Christian doctrine is Christocentric, meaning that Christ is held to be the sole full and true revelation of the will of God for humanity. In a Christocentric view, the elements of truth in other religions are understood in relation to the fullness of truth found in Christ. God is nevertheless understood to be free of human constructions. Therefore, God the Holy Spirit is understood as the power who guides non-Christians in their search for truth, which is held to be a search for the mind of Christ, even if "anonymously," in the phrase of Catholic theologian Karl Rahner. For those who support this view, anonymous Christians belong to Christ now and forever and lead a life fit for Jesus' commandment to love, even though they never explicitly understand the meaning of their life in Christian terms.

While the conciliar document Nostra aetate has fostered widespread dialogue, the declaration Dominus Iesus nevertheless reaffirms the centrality of the person of Jesus Christ in the spiritual and cultural identity of Christians, rejecting various forms of syncretism.

Pope John Paul II was a major advocate of interfaith dialogue, promoting meetings in Assisi in the 1980s. Pope Benedict XVI took a more moderate and cautious approach, stressing the need for intercultural dialogue, but reasserting Christian theological identity in the revelation of Jesus of Nazareth in a book published with Marcello Pera in 2004. In 2013, Pope Francis became the first Catholic leader to call for "sincere and rigorous" interbelief dialogue with atheists, both to counter the assertion that Christianity is necessarily an "expression of darkness of superstition that is opposed to the light of reason," and to assert that "dialogue is not a secondary accessory of the existence of the believer" but instead is a "profound and indispensable expression ... [of] faith [that] is not intransigent, but grows in coexistence that respects the other."

In traditional Christian doctrine, the value of inter-religious dialogue had been confined to acts of love and understanding toward others either as anonymous Christians or as potential converts.

In mainline Protestant traditions, however, as well as in the emerging church, these doctrinal constraints have largely been cast off. Many theologians, pastors, and lay people from these traditions do not hold to uniquely Christocentric understandings of how God was in Christ. They engage deeply in interfaith dialogue as learners, not converters, and desire to celebrate as fully as possible the many paths to God.

Much focus in Christian interfaith dialogue has been put on Christian–Jewish reconciliation. One of the oldest successful dialogues between Jews and Christians has been taking place in Mobile, Alabama. It began in the wake of the call of the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965) of the Roman Catholic Church for increased understanding between Christians and Jews. The organization has recently moved its center of activity to Spring Hill College, a Catholic Jesuit institution of higher learning located in Mobile. Reconciliation has been successful on many levels, but has been somewhat complicated by the Arab-Israeli conflict in the Middle East, where a significant minority of Arabs are Christian.

Judaism

The Modern Orthodox movement allows narrow exchanges on social issues, while warning to be cautious in discussion of doctrine. Reform Judaism, Reconstructionist Judaism and Conservative Judaism encourage interfaith dialogue.

Building positive relations between Jews and members of other religious communities has been an integral component of Reform Judaism's "DNA" since the movement was founded in Germany during the early 19th century, according to Rabbi A. James Rudin. It began with Israel Jacobson, a layman and pioneer in the development of what emerged as Reform Judaism, who established an innovative religious school in Sessen, Germany in 1801 that initially had 40 Jewish and 20 Christian students. "Jacobson's innovation of a 'mixed' student body reflected his hopes for a radiant future between Jews and Christians."

Moravian born Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, who founded the Reform movement in the United States, sought close relations with Christian church leaders. To that end, he published a series of lectures in 1883 entitled "Judaism and Christianity: Their Agreements and Disagreements". Wise emphasized what he believed linked the two religions in an inextricable theological and human bond: the biblical "Sinaitic revelation" as "... the acknowledged law of God". Rabbi Leo Baeck, the leader of the German Jewish community who survived his incarceration in the Terezin concentration camp, offered these words in his 1949 presidential address to the World Union for Progressive Judaism in London: "...as in a great period of the Middle Ages, [Jews and Muslims] are ...almost compelled to face each other... not only in the sphere of policy [the State of Israel in the Middle East], but also in the sphere of religion; there is the great hope... they will ...meet each other on joint roads, in joint tasks, in joint confidences in the future. There is the great hope that Judaism can thus become the builder of a bridge, the 'pontifex' between East and West."

In the 1950s and 60s, as interfaith civic partnerships between Jews and Christians in the United States became more numerous, especially in the suburbs, the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (now the Union for Reform Judaism, URJ) created a department mainly to promote positive Christian-Jewish relations and civic partnerships. Interfaith relations have since been expanded to include Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, and members of other faith communities.

In 2013, Rabbi Marc Schneier and Imam Shamsi Ali coauthored a book Sons of Abraham: A Candid Conversation about the Issues That Divide and Unite Jews and Muslims. Schneier and Ali write about the importance of civil interfaith discussions. Based on their experience, Schneier and Ali believe that other "Jews and Muslims can realize that they are actually more united than divided in their core beliefs".

Interests in interfaith relations require an awareness of the range of Jewish views on such subjects as mission and the holy land.

Islam

Islam has long encouraged dialogue to reach truth. Dialogue is particularly encouraged amongst the People of the Book (Jews, Christians and Muslims) as the Quran states, "Say, "O People of the Scripture, come to a word that is equitable between us and you – that we will not worship except Allah and not associate anything with Him and not take one another as lords instead of Allah." But if they turn away, then say, "Bear witness that we are Muslims [submitting to Him]" [3:64].

Many traditional and religious texts and customs of the faith have encouraged this, including specific verses in the Quran, such as: "O people! Behold, we have created you from a male and a female and have made you into nations and tribes so that you might come to know one another. Verily, the noblest of you in the sight of God is the one who is most deeply conscious of Him. Behold, God is all-knowing, all-aware" [Qur'an 49:13].

In recent times, Muslim theologians have advocated inter-faith dialogue on a large scale, something which is new in a political sense. The declaration A Common Word of 2007 was a public first in Christian-Islam relations, trying to work out a moral common ground on many social issues. This common ground was stated as "part of the very foundational principles of both faiths: love of the One God, and love of the neighbour". The declaration asserted that "these principles are found over and over again in the sacred texts of Islam and Christianity".

- Interfaith dialogue integral to Islam

A 2003 book called Progressive Muslims: On Justice, Gender, and Pluralism contains a chapter by Amir Hussain on "Muslims, Pluralism, and Interfaith Dialogue" in which he shows how interfaith dialogue has been an integral part of Islam from its beginning. Hussain writes that "Islam would not have developed if it had not been for interfaith dialogue". From his "first revelation" for the rest of his life, Muhammad was "engaged in interfaith dialogue" and "pluralism and interfaith dialogue" have always been important to Islam. For example, when some of Muhammad's followers suffered "physical persecution" in Mecca, he sent them to Abyssinia, a Christian nation, where they were "welcomed and accepted" by the Christian king. Another example is Córdoba, Andalusia in Muslim Spain, in the ninth and tenth centuries. Córdoba was "one of the most important cities in the history of the world". In it, "Christians and Jews were involved in the Royal Court and the intellectual life of the city". Thus, there is "a history of Muslims, Jews, Christians, and other religious traditions living together in a pluralistic society". Turning to the present, Hussain writes that in spite of Islam's history of "pluralism and interfaith dialogue", Muslims now face the challenge of conflicting passages in the Qur'an some of which support interfaith "bridge-building", but others can be used "justify mutual exclusion".

In October 2010, as a representative of Shia Islam, Ayatollah Mostafa Mohaghegh Damad, professor at the Shahid Beheshti University of Tehran, addressed the Special Assembly for the Middle East of the Synod of Catholic Bishops. In the address he spoke about "the rapport between Islam and Christianity" that has existed throughout the history of Islam as one of "friendship, respect and mutual understanding".

- Book about Jewish–Muslim dialogue

In 2013, Rabbi Marc Schneier (Jewish) and Imam Shamsi Ali (Muslim) coauthored a book Sons of Abraham with the subtitle A Candid Conversation about the Issues That Divide and Unite Jews and Muslims. As Rabbi Marc Schneier and Imam Shamsi Ali show, "by reaching a fuller understanding of one another's faith traditions, Jews and Muslims can realize that they are actually more united than divided in their core beliefs". By their fuller understanding, they became "defenders of each other's religion, denouncing the twin threats of anti-Semitism and Islamophobia and promoting interfaith cooperation". In the book, regarding the state of Jewish-Muslim dialogue, although Rabbi Schneier acknowledges a "tremendous growth", he does not think that "we are where we want to be".

Ahmadiyya

The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community was founded in 1889. Its members "exceeding tens of millions" live in 206 countries. It rejects "terrorism in any form". It broadcasts its "message of peace and tolerance" over a satellite television channel MTA International Live Streaming, on its internet website, and by its Islam International Publications. A 2010 story in the BBC News said that the Ahmadi "is regarded by orthodox Muslims as heretical", The story also reported persecution and violent attacks against the Ahmadi.

According to the Ahmadiyya understanding, interfaith dialogues are an integral part of developing inter-religious peace and the establishment of peace. The Ahmadiyya Community has been organising interfaith events locally and nationally in various parts of the world in order to develop a better atmosphere of love and understanding between faiths. Various speakers are invited to deliver a talk on how peace can be established from their own or religious perspectives.

Preconditions

In her 2008 book The Im-Possibility of Interreligious Dialogue, Catherine Cornille outlines her preconditions for "constructive and enriching dialogue between religions". In summary, they include "doctrinal humility, commitment to a particular religion, interconnection, empathy, and hospitality". In full, they include the following:

- humility (causes a respect of a person's view of other religions)

- commitment (causes a commitment to faith that simultaneously accept tolerance to other faiths)

- interconnection (causes the recognition of shared common challenges such as the reconciliation of families)

- empathy (causes someone to view another religion from the perspective of its believers)

- hospitability (like the tent of Abraham, that was open on all four sides as a sign of hospitality to any newcomer).

Breaking down the walls that divides faiths while respecting the uniqueness of each tradition requires the courageous embrace of all these preconditions.

In 2016, President Obama made two speeches that outlined preconditions for meaningful interfaith dialogue: On February 3, 2016, he spoke at the Islamic Society of Baltimore and on February 4, 2016, at the National Prayer Breakfast. The eight principles of interfaith relations as outlined by Obama were as follows:

- Relationship building requires visiting each other.

- Relationship requires learning about the others' history.

- Relationship requires an appreciation of the other.

- Relationship requires telling the truth.

- Relationships depend on living up to our core theological principles and values.

- Relationships offer a clear-headed understanding of our enemies.

- Relationships help us overcome fear.

- Relationship requires solidarity.

United Nations support

The United Nations Alliance of Civilizations is an initiative to prevent violence and support social cohesion by promoting intercultural and interfaith dialogue. The UNAOC was proposed by the President of the Spanish Government, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero at the 59th General Assembly of the United Nations in 2005. It was co-sponsored by the Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

In 2008, Anwarul Karim Chowdhury said: "Interfaith dialogue is absolutely essential, relevant, and necessary. ... If 2009 is to truly be the Year of Interfaith Cooperation, the U.N. urgently needs to appoint an interfaith representative at a senior level in the Secretariat."

The Republic of the Philippines will host a Special Non-Aligned Movement Ministerial Meeting on Interfaith Dialogue and Cooperation for Peace and Development from March 16 to 18 in Manila. During the meeting, to be attended by ministers of foreign affairs of the NAM member countries, a declaration in support of interfaith dialogue initiatives will be adopted. An accompanying event will involve civil society activities.

In 2010, HM King Abdullah II addressed the 65th UN General Assembly and proposed the idea for a 'World Interfaith Harmony Week' to further broaden his goals of faith-driven world harmony by extending his call beyond the Muslim and Christian community to include people of all beliefs, those with no set religious beliefs as well. A few weeks later, HRH Prince Ghazi bin Muhammad presented the proposal to the UN General Assembly, where it was adopted unanimously as a UN Observance Event. The first week of February, every year, has been declared a UN World Interfaith Harmony Week. The Royal Islamic Strategic Studies Centre released a document which summarises the key events leading up to the UN resolution as well as documenting some Letters of Support and Events held in honour of the week.

Criticism

The Islamist group Hizb ut-Tahrir rejects the concept of interfaith dialogue, stating that it is a western tool to enforce non-Islamic policies in the Islamic world.

Many Traditionalist Catholics, not merely Sedevacantists or the Society of St. Pius X, are critical of interfaith dialogue as a harmful novelty arising after the Second Vatican Council, which is said to have altered the previous notion of the Catholic Church's supremacy over other religious groups or bodies, as well as demoted traditional practices associated with traditional Roman Catholicism. In addition, these Catholics contend that, for the sake of collegial peace, tolerance and mutual understanding, interreligious dialogue devalues the divinity of Jesus Christ and the revelation of the Triune God by placing Christianity on the same footing as other religions that worship other deities. Evangelical Christians also critical for dialogues with Catholics.

Religious sociologist Peter L. Berger argued that one can reject interfaith dialogue on moral grounds in certain cases. The example he gave was that of a dialogue with imams who legitimate ISIS, saying such discussions ought to be avoided so as not to legitimate a morally repugnant theology.

In the case of Hinduism, it has been argued that the so-called interfaith "dialogue ... has [in fact] become the harbinger of violence. This is not because 'outsiders' have studied Hinduism or because the Hindu participants are religious 'fundamentalists' but because of the logical requirements of such a dialogue". With a detailed analysis of "two examples from Hinduism studies", S.N. Balagangadhara and Sarah Claerhout argue that, "in certain dialogical situations, the requirements of reason conflict with the requirements of morality".

The theological foundations of interreligious dialogue have also been critiqued on the grounds that any interpretation of another faith tradition will be predicated on a particular cultural, historical and anthropological perspective

Some critics of interfaith dialogue may not object to dialogue itself, but instead are critical of specific events claiming to carry on the dialogue. For example, the French Algerian prelate Pierre Claverie was at times critical of formal inter-religious conferences between Christians and Muslims which he felt remained too basic and surface-level. He shunned those meetings since he believed them to be generators of slogans and for the glossing over of theological differences. However, he had such an excellent knowledge of Islam that the people of Oran called him "the Bishop of the Muslims" which was a title that must have pleased him since he had dreamed of establishing true dialogue among all believers irrespective of faith or creed. Claverie also believed that the Islamic faith was authentic in practice focusing on people rather than on theories. He said that: "dialogue is a work to which we must return without pause: it alone lets us disarm the fanaticism; both our own and that of the other". He also said that "Islam knows how to be tolerant". In 1974 he joined a branch of Cimade which was a French NGO dedicated to aiding the oppressed and minorities.

![{\displaystyle R_{p}=k_{p}[\mathrm {M} ][\mathrm {P} ^{\bullet }]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fa19feaf22640e65f732c69f56b85947a1402a52)

![{\displaystyle [\mathrm {M} ]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6995ed94bf3af4ae97e2bf0413f15dd8e895d3a2)

![{\textstyle [\mathrm {P} ^{\bullet }]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8a1e52291ba4eecafea6a92823c0ea1e5a5b59a4)

![{\displaystyle [\mathrm {P} ^{\bullet }]={\frac {N_{\mathrm {micelles} }}{2N_{\mathrm {A} }}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/654f5253c3090b21f48798ac181d2ee8580bd474)

![{\displaystyle R_{p}=k_{p}[\mathrm {M} ]{\frac {N_{\mathrm {micelles} }}{2N_{\mathrm {A} }}}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9cd8ee08d11a5e51f3d40e011e1bc720404ac6cd)