Contemporary Native American issues in the United States are issues arising in the late 20th century and early 21st century which affect Native Americans in the United States. Many issues stem from the subjugation of Native Americans in society, including societal discrimination, racism, cultural appropriation through sports mascots, and depictions in art. Native Americans have also been subject to substantial historical and intergenerational trauma that have resulted in significant public health issues like alcohol use disorder and risk of suicide.

Demographics

A little over one third of the 2,786,652 Native Americans in the United States live in three states: California at 413,382, Arizona at 294,137 and Oklahoma at 279,559. 70% of Native Americans lived in urban areas in 2012, up from 45% in 1970 and 8% in 1940. Many Urban Indians live in cities due to forced relocation by the United States government with legislative pieces such as the Indian Relocation Act of 1956 or due to the need for healthcare services not provided on or near reservations and tribe locations.

In the early 21st century, Native American communities have exhibited continual growth and revival, playing a larger role in the American economy and in the lives of Native Americans. Communities have consistently formed governments that administer services such as firefighting, natural resource management, social programs, health care, housing and law enforcement. Numerous tribes have founded tribal colleges.

Most Native American communities have established court systems to adjudicate matters related to local ordinances. Most also look to various forms of moral and social authority, such as forms of restorative justice, vested in the traditional culture of the tribal nation. Native American professionals have founded associations in journalism, law, medicine and other fields to encourage students in these fields, provide professional training and networking opportunities, and entry into mainstream institutions.

To address the housing needs of Native Americans, Congress passed the Native American Housing and Self Determination Act (NAHASDA) in 1996. This legislation replaced public housing built by the BIA and other 1937 Housing Act programs directed towards Indian Housing Authorities, with a block-grant program. It provides funds to be administered by the Tribes to develop their own housing.

Terminology differences

Native Americans are also commonly known as Indians or American Indians. A 1995 U.S. Census Bureau survey found that more Native Americans in the United States preferred American Indian to Native American. Most American Indians are comfortable with Indian, American Indian, and Native American, and the terms are often used interchangeably.

They have also been known as Aboriginal Americans, Amerindians, Amerinds, Colored, First Americans, Native Indians, Indigenous, Original Americans, Red Indians, Redskins or Red Men. The term Native American was introduced in the United States by academics in preference to the older term Indian to distinguish the indigenous peoples of the Americas from the people of India. Some academics believe that the term Indian should be considered outdated or offensive while many indigenous Americans, however, prefer the term American Indian.

Criticism of the neologism Native American comes from diverse sources. Some American Indians question the term Native American because, they argue, it serves to ease the conscience of "white America" with regard to past injustices done to American Indians by effectively eliminating "Indians" from the present. Others (both Indians and non-Indians) argue that Native American is problematic because "native of" literally means "born in," so any person born in the Americas could be considered "native". Others point out that anyone born in the United States is technically native to America, so "native" is sometimes substituted for "indigenous." The compound "Native American" is generally capitalized to differentiate the reference to the indigenous peoples. Russell Means, an American Indian activist, opposes the term Native American because he believes it was imposed by the government without the consent of American Indians. He has also argued that the use of the word Indian derives not from a confusion with India but from a Spanish expression En Dio, meaning "in God".

Societal discrimination and racism

Universities have conducted relatively little public opinion research on attitudes toward Native Americans. In 2007 the non-partisan Public Agenda organization conducted a focus group study. Most non-Native Americans admitted they rarely encountered Native Americans in their daily lives. While sympathetic toward Native Americans and expressing regret over the past, most people had only a vague understanding of the problems facing Native Americans today. For their part, Native Americans told researchers that they believed they continued to face prejudice and mistreatment in the broader society.

Affirmative action issues

Federal contractors and subcontractors such as businesses and educational institutions are legally required to adopt equal opportunity employment and affirmative action measures intended to prevent discrimination against employees or applicants for employment on the basis of "color, religion, sex, or national origin". For this purpose, an American Indian or Alaska Native is defined as "A person having origins in any of the original peoples of North and South America (including Central America), and who maintains a tribal affiliation or community attachment." However, self-reporting is permitted, "Educational Institutions and Other Recipients Should Allow Students and Staff To Self-Identify Their Race and Ethnicity Unless Self-Identification Is Not Practicable or Feasible."

Self-reporting opens the door to "box checking" by people, who, despite not having a substantial relationship to Native American culture, either innocently or fraudulently "check the box" for Native American. On August 15, 2011, the American Bar Association passed a resolution recommending that law schools require supporting information such as evidence of tribal enrollment or connection with Native American culture.

Racial achievement gap regarding language

To evade a shift to English, some Native American tribes have initiated language immersion schools for children, where a native Indian language is the medium of instruction. For example, the Cherokee Nation instigated a 10-year language preservation plan that involved growing new fluent speakers of the Cherokee language from childhood on up through school immersion programs as well as a collaborative community effort to continue to use the language at home. This plan was part of an ambitious goal that in 50 years, 80% or more of the Cherokee people will be fluent in the language. The Cherokee Preservation Foundation has invested $3 million into opening schools, training teachers, and developing curricula for language education, as well as initiating community gatherings where the language can be actively used. Formed in 2006, the Kituwah Preservation & Education Program (KPEP) on the Qualla Boundary focuses on language immersion programs for children from birth to fifth grade, developing cultural resources for the general public and community language programs to foster the Cherokee language among adults.

There is also a Cherokee language immersion school in Tahlequah, Oklahoma that educates students from pre-school through eighth grade. Because Oklahoma's official language is English, Cherokee immersion students are hindered when taking state-mandated tests because they have little competence in English. The Department of Education of Oklahoma said that in 2012 state tests: 11% of the school's sixth-graders showed proficiency in math, and 25% showed proficiency in reading; 31% of the seventh-graders showed proficiency in math, and 87% showed proficiency in reading; 50% of the eighth-graders showed proficiency in math, and 78% showed proficiency in reading. The Oklahoma Department of Education listed the charter school as a Targeted Intervention school, meaning the school was identified as a low-performing school but has not so that it was a Priority School. Ultimately, the school made a C, or a 2.33 grade point average on the state's A-F report card system. The report card shows the school getting an F in mathematics achievement and mathematics growth, a C in social studies achievement, a D in reading achievement, and an A in reading growth and student attendance. “The C we made is tremendous,” said school principal Holly Davis, “[t]here is no English instruction in our school's younger grades, and we gave them this test in English." She said she had anticipated the low grade because it was the school's first year as a state-funded charter school, and many students had difficulty with English. Eighth graders who graduate from the Tahlequah immersion school are fluent speakers of the language, and they usually go on to attend Sequoyah High School where classes are taught in both English and Cherokee.

Native American mascots in sports

American Indian activists in the United States and Canada have criticized the use of Native American mascots in sports as perpetuating stereotypes. European Americans have had a history of "playing Indian" that dates back to at least the 18th century. While supporters of the mascots say they embody the heroism of Native American warriors, AIM particularly has criticized the use of mascots as offensive and demeaning. In fact, many Native Americans compare this discrimination to examples for other demographics like black face for African Americans.

Could you imagine people mocking African Americans in black face at a game?" he said. "Yet go to a game where there is a team with an Indian name and you will see fans with war paint on their faces. Is this not the equivalent to black face?

— "Native American Mascots Big Issue in College Sports", Teaching Tolerance, May 9, 2001

While many universities and professional sports teams (for example, the Cleveland Indians, who had a Chief Wahoo) no longer use such images without consultation and approval by the respective nation, some lower-level schools continue to do so. However, others like Tomales Bay High and Sequoia High in the Bay Area of California, have retired their Indian mascots.

In August 2005, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) banned the use of "hostile and abusive" Native American mascots in postseason tournaments. An exception was made to allow the use of tribal names if approved by that tribe (such as the Seminole Tribe of Florida's approving use of their name for the team of Florida State University.)

Environmental justice

Environmental justice academic case studies examine the erasure of indigenous culture and ways of life, resource exploitation, destruction of sacred land, environmental and indigenous health, and climate justice. From the arrival of white settlers, explorers and colonizers, Native Americans have suffered from genocide, introduced diseases, warfare, and the legacy of environmental racism persists in modern day. The environmental justice movement has largely left out the Native American experience, but findings have shown that Native land is being, and has been, used for landfills, dump sites, and locations to test nuclear weapons. However, while these uses cause harm to the peoples health, they are not always unwanted. The Mescalero Apache welcomed the proposal to have a monitored retrievable nuclear waste storage facility built on their land because over one-third of the tribal citizens were unemployed, and they lacked enough housing and any sort of school system. Jamie Vickery and Lori M. Hunter have stated that the natives are being coerced into accepting the nuclear waste storage facility by their own economic hardships, which in turn has been caused by the US government direct exploitation and marginalization.

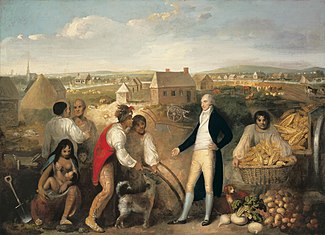

Historical depictions in art

A number of 19th and 20th-century United States and Canadian painters, often motivated by a desire to document and preserve Native culture, specialized in Native American subjects. Among the most prominent of these were Elbridge Ayer Burbank, George Catlin, Seth Eastman, Paul Kane, W. Langdon Kihn, Charles Bird King, Joseph Henry Sharp and John Mix Stanley. While many 19th-century images of Native Americans conveyed negative and unrepresentative messages, artists such as Charles Bird King portrayed Native American delegates with accuracy. His paintings are often used as records for Native American formal dress and customs. During the 16th century, the artist John White made watercolors and engravings of the people native to the southeastern states. John White's images were, for the most part, faithful likenesses of the people he observed. However, some like artist Theodore de Bry used White's original watercolors to alter the poses and features of White's figures to make them appear more European.

There are also many depictions of Native Americans on federal buildings, statues, and memorials. During the construction of the Capitol building in the early 19th century, the U.S. government commissioned a series of four relief panels to crown the doorway of the Rotunda. The reliefs encapsulate a vision of European—Native American relations that had assumed mythic historical proportions by the 19th century. The four panels depict: The Preservation of Captain Smith by Pocahontas (1825) by Antonio Capellano, The Landing of the Pilgrims (1825) and The Conflict of Daniel Boone and the Indians (1826–27) by Enrico Causici and William Penn’s Treaty with the Indians (1827) by Nicholas Gevelot. The reliefs by European sculptors present versions of the Europeans and the Native Americans, in which the Europeans appear refined and the natives appear ferocious.

In the 20th century, early portrayals of Native Americans in movies and television roles were first performed by European Americans dressed in mock traditional attire. Examples included The Last of the Mohicans (1920), Hawkeye and the Last of the Mohicans (1957), and F Troop (1965–67). In later decades, Native American actors such as Jay Silverheels in The Lone Ranger television series (1949–57) came to prominence. Roles of Native Americans were limited and not reflective of Native American culture. For years, Native people on U.S. television were relegated to secondary, subordinate roles relative to the white protagonists as shown in notable works like Cheyenne (1957–1963) and Law of the Plainsman (1959–1963).

By the 1970s some Native American film roles began to show more complexity, such as those in Little Big Man (1970), Billy Jack (1971), and The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976) which depicted Native Americans in important lead and supporting roles. Regardless, the European narrative perspective was prioritized in popular media. The "sympathetic" yet contradictory film Dances With Wolves (1990) intentionally, according to Ella Shohat and Robert Stam, related the Lakota story through a Euro-American voice for wider impact among a general audience. Like the 1992 remake of The Last of the Mohicans and Geronimo: An American Legend (1993), Dances with Wolves employed a number of Native American actors, and made an effort to portray Indigenous languages. Many film scholars and Native Americans still criticize films like Dances with Wolves for its 'white savior' narrative that asserts European-Americans are the necessary saviors of people of color like Native Americans. In 1996, Plains Cree actor Michael Greyeyes would play renowned Native American warrior Crazy Horse in the 1996 television film Crazy Horse. Greyeyes would also later play renowned Sioux chief Sitting Bull in the 2017 movie Woman Walks Ahead.

The 1998 film Smoke Signals, which was set on the Coeur D'Alene Reservation and discussed hardships of present-day American Indian families living on reservations, featured numerous Native American actors as well. The film was also the first feature film to be produced and directed by Native Americans, and also the first feature to include an exclusive Native American cast. At the annual Sundance Film Festival, Smoke Signals would win the Audience Award and it's producer Chris Eyre, an enrolled member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma, would win the Filmmaker's Trophy.

Many documentaries have been created partly in response to unbalanced coverage of Native American perspectives in history and partly to educate the public about the shared history of conflict between Native Americans and European colonists. In 2004 producer Guy Perrotta presented the film Mystic Voices: The Story of the Pequot War (2004), a television documentary on the Pequot War, which was the first major conflict between European colonists and indigenous peoples in North America. The documentary portrayed the conflict as a struggle between different value systems, which included not only the Pequot, but a number of other Native American tribes in Massachusetts, most of which allied with the colonists. Perrotta and Charles Clemmons, another producer, intended to increase public understanding of the significance of this early event. In 2009 We Shall Remain (2009), a television documentary by Ric Burns and part of the American Experience series, presented a five-episode series "from a Native American perspective". It represented "an unprecedented collaboration between Native and non-Native filmmakers and involves Native advisors and scholars at all levels of the project." The five episodes explore the impact of King Philip's War on the northeastern tribes, the "Native American confederacy" of Tecumseh's War, the US-forced relocation of Southeastern tribes known as the Trail of Tears, the pursuit and capture of Geronimo and the Apache Wars, and concludes with the Wounded Knee incident, participation by the American Indian Movement, and the increasing resurgence of modern Native cultures since.

Education

The majority of Native American youth attend public schools that are not tribally controlled. For those Native Americans who view education as a means of preserving their ancient knowledge, culture and language, this raises questions about tribal self-determination.

History

The first educational institutions for Native Americans were founded by missionaries. The primary objectives of missionary education were to civilize, individualize and Christianize Native American youth. Early colonial colleges, Harvard, William and Mary, Dartmouth and Hamilton, were established in part to educate Native Americans. Dartmouth College was the first college founded primarily for the education of Native Americans. Lack of support from the public and infighting amongst the missionaries led to the closure of most missionary schools in the 19th century.

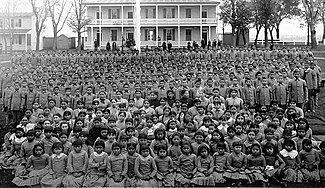

During the 19th century, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) began to fund Native American education. The BIA founded boarding schools for Native American youth that were modeled after the off-reservation Carlisle Indian Industrial School. These government-run boarding schools were located at former military posts and used an assimilationist education model. Native American students were enrolled in the "outing system," a system where they were placed in white homes to work during the summers. Between 1870 and 1920, the federal government increased its role in providing Native American elementary and secondary school education, and boarding schools became the predominant form of Native American education.

In the 1960s, the Native American self-determination movement pushed for more tribal involvement in education. The Higher Education Act of 1965 provided for the development of postsecondary institutions for minority students. The passage of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 gave tribes the power to control their funds for welfare and education.

Today, approximately 92 percent of Native American youth attend public schools, and approximately eight percent attend schools operated or funded by the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE). Tribally controlled education has become a key part of the Native American self-determination movement.

Tribally controlled schools

In the early 1800s, the first tribally controlled schools were established by five Southeastern tribes: the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Cree and Seminole. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 and other federal forced relocation policies shut down these tribally controlled schools. The next 100 years of Native American education were dominated by missionary and federal run off-reservation boarding schools.

The 1960s saw the emergence of the Native American self-determination movement and a renewed support for tribally controlled education. The Bilingual Education Act (BEA) was passed in 1968 and recognized the need for community-controlled bilingual programs.

In 1965, the Navajo Education Department in cooperation with the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), the U.S. Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO), and a nonprofit (DINE) established the first school with an all-Indian governing board—Rough Rock Community School. In 1968, Diné College (Navajo Community College originally) was established as the first tribally controlled college. Other tribes followed suit and in 1971 formed the Coalition of Indian-Controlled Schools. This coalition drove the creation and enactment of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975.

In the years following the passage of the 1972 Indian Education Act and the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975, more than 75 tribally controlled primary and secondary schools, and 24 community colleges were established.

In 1973, the first six tribally controlled colleges joined together to found the American Indian Higher Education Consortium (AIHEC). Today, 37 tribally controlled colleges are part of the AIHEC.

The passage of the Native American Languages Act of 1990 guaranteed Native Americans the right to maintain and promote their languages and cultural systems through educational programs.

Currently, the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) oversees 183 elementary and secondary schools, 126 of these schools are tribally controlled.

Contemporary challenges

Native American communities face significant educational challenges, such as inadequate school funding, lack of qualified teachers, student achievement gap, underrepresentation in higher education and high dropout rates.

Tribally controlled schools receive funding directly from the BIE. The implementation of the No Child Left Behind Act in 2001 at a state level made it so that tribally controlled schools had to assume responsibility for state-level tasks without support. The Act linked funding to test scores, which resulted in decreased funding for many tribally controlled schools.

Native American students have the lowest high school graduation rates of any minority in the United States. Dropout rates amongst Native American youth are also the highest in the nation. There is a 15 percent drop-out rate amongst Native American 16- to 24-year-olds, compared to the national average of 9.9 percent.

Native American students are underrepresented in higher education at the bachelor's, master's and doctoral levels. The recruitment and retention of Native American students at a university level is a major issue. Native American professors are also underrepresented; they make up less than one percent of higher education faculty.

There is a need for adequately trained teachers and appropriate curriculum in Native American education. Western education models are not hospitable to indigenous epistemologies. The No Child Left Behind Act and English-only ballot initiatives make it difficult to adopt culturally relevant curriculum.

STEM education

Tribes are attempting to incorporate Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, STEM, curriculum into their education systems, but there is as yet no consensus on how to do so.

Native Americans are underrepresented by a factor of at least four in STEM disciplines. In 2012, Native American students accounted for only 0.6 percent of bachelor's degrees, 0.4 percent of master's degrees and 0.2 percent of doctoral degrees in science and engineering.

Benefits

Some tribes have used technology to preserve their culture and languages through digital storytelling, computer language platforms, audio recordings, webpages and other forms of media.

Technology also contributes to economic and educational development. STEM knowledge helps Native youth enter into Western jobs. Increased representation in STEM fields could aid the Native American self-determination movement. Native Americans in STEM could assume the role of controlling their own land and resources.

Concerns

Native and non-native scholars have developed curricula to integrate Western knowledge with indigenous knowledge, but there is no agreement on a best approach.

The federal government has funded projects in collaboration with Native American schools that focus on the use of technology to support culturally responsive curriculum. The implementation of these technologies and curricula remains almost non-existent at an institutional level.

Elders in tribal communities often fear that exposure to technology will result in assimilation. Underrepresentation in digital content contributes to this fear.

Digital equity is a concern as tribes have to appropriate resources for technological infrastructure maintenance, develop standards to protect sacred tribal information and determine how to promote tribal goals.

STEM curriculum is often dismissive of Native worldviews. Western STEM models contradict Native science because they emphasize individuality and humans as separate from the natural world. Science curriculum does not respect cultural taboos. Native American students view human and animal dissections as the most problematic STEM activities. Research suggests that a majority of Native American students would be more likely to take STEM classes if the curriculum was more respectful of taboos.

Potential solutions

Practices proven to increase Native student's interest in STEM are: caring mentors, hands-on learning, observational learning, collaboration, real-world applications and community involvement. Some tribal STEM programs are employing community-based science curriculum. The characteristics of community-based science curriculum are that it is local, place-based, hands-on, involves the community, incorporates system-thinking and a holistic view a science and explores multiple epistemologies.

The Science, Technology, Society (STS) model asks students to explore a problem that is relevant to them and their community. It incorporates human experiential context with science. Other models emphasize the value of incorporating Traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and "indigenous realism," the recognition of the interconnectedness of everything in nature.

The Maker culture, or maker movement, is another model that has the potential to support minority youth in learning STEM. The Hackerspace can provide a positive, non-school based STEM learning experience for youth who are marginalized in school.

Crime on reservations

Prosecution of serious crime, historically endemic on reservations, was required by the 1885 Major Crimes Act, 18 U.S.C. §§1153, 3242, and court decisions to be investigated by the federal government, usually the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and prosecuted by United States Attorneys of the United States federal judicial district in which the reservation lies. An investigation by The Denver Post in 2007 found that crimes in Indian Country have been a low priority both with the FBI and most federal prosecutors. As of November 2012 federal resources were being reduced while high rates of crime continued to rise in Indian Country.

Often serious crimes have been either poorly investigated or prosecution has been declined. Tribal courts were limited to sentences of one year or less, until on July 29, 2010, the Tribal Law and Order Act was enacted which in some measure reforms the system permitting tribal courts to impose sentences of up to three years provided proceedings are recorded and additional rights are extended to defendants. The Justice Department on January 11, 2010, initiated the Indian Country Law Enforcement Initiative which recognizes problems with law enforcement on reservations and assigns top priority to solving existing problems.

The Department of Justice recognizes the unique legal relationship that the United States has with federally recognized tribes. As one aspect of this relationship, in much of Indian Country, the Justice Department alone has the authority to seek a conviction that carries an appropriate potential sentence when a serious crime has been committed. Our role as the primary prosecutor of serious crimes makes our responsibility to citizens in Indian Country unique and mandatory. Accordingly, public safety in tribal communities is a top priority for the Department of Justice.

Emphasis was placed on improving prosecution of crimes involving domestic violence and sexual assault.

Passed in 1953, Public Law 280 (PL 280) gave jurisdiction over criminal offenses involving Indians in Indian Country to certain States and allowed other States to assume jurisdiction. Subsequent legislation allowed States to retrocede jurisdiction, which has occurred in some areas. Some PL 280 reservations have experienced jurisdictional confusion, tribal discontent, and litigation, compounded by the lack of data on crime rates and law enforcement response.

As of 2012, a high incidence of rape continued to impact Native American women and Alaskan native women. According to the Justice Department 1 in 3 women have suffered rape or attempted rape, more than twice the national rate. 80% of Native American sexual assault victims report that their attacker was "non-Indian". As of 2013 inclusion of offenses by non-native men against native women in the Violence Against Women Act continued to present difficulties over the question of whether defendants who are not tribal members would be treated fairly by tribal courts or afforded constitutional guarantees. On June 6, 2012, the Justice Department announced a pilot plan to establish joint federal-tribal response teams on 6 Montana reservations to combat rape and sexual assault.

Gambling industry

Gambling has become a leading industry. Casinos operated by many Native American governments in the United States are creating a stream of gambling revenue that some communities are beginning to use as leverage to build diversified economies. Native American communities have waged and prevailed in legal battles to assure recognition of rights to self-determination and to use of natural resources. Some of those rights, known as treaty rights, are enumerated in early treaties signed with the young United States government. These casinos have brought an influx of money to the tribes; according to tribal accounting firm Joseph Eve, CPAs, the average net profit of Indian casinos is 38.85%.

Tribal sovereignty has become a cornerstone of American jurisprudence, and at least on the surface, in national legislative policies. Although many Native American tribes have casinos, the impact of Native American gaming is widely debated. Some tribes, such as the Winnemem Wintu of Redding, California, feel that casinos and their proceeds destroy culture from the inside out. These tribes refuse to participate in the gambling industry.

Public health

As of 2004, according to the United States Commission on Civil Rights: "Native Americans die of diabetes, alcohol use disorder, tuberculosis, suicide, and other health conditions at shocking rates. Beyond disturbingly high mortality rates, Native Americans also suffer a significantly lower health status and disproportionate rates of disease compared with all other Americans."

In addition to increasing numbers of American Indians entering the fields of community health and medicine, agencies working with Native American communities have sought partnerships, representatives of policy and program boards, and other ways to learn and respect their traditions and to integrate the benefits of Western medicine within their own cultural practices.

A comprehensive review of 32 articles about Indigenous Historical Trauma and its relation to health outcomes in Indigenous populations affirmed that historical hardships experienced by previous Indigenous generations can have a transmitted impact on the health and wellbeing of current Indigenous generations. The articles examined Indigenous populations in both the United States and Canada. The systematic review resulted in three categories of research.

- 19 articles focused on health outcomes for Indigenous people who experienced historical loss either personally or transgenerationally. Historical loss was measured in accordance with the Historical Loss Scale created by Whitbeck, Adams, et al.(2004). Twelve types of loss were identified, including "loss of our land" “loss of our language", and "loss of our traditional spiritual ways".

- 11 articles focused on the theme of residential school ancestry studies which took a closer look at Indigenous people mainstreamed into Indian boarding school systems and the correlated health impacts of those individuals or the relatives of those individuals.

- three articles were categorized as "other". Two of the articles focused on the outcomes of a psychoeducation intervention and the remaining article examined the health outcomes of families who had a grandparent subjected to a relocation program.

Alcohol use disorder

The community suffers a vulnerability to and a disproportionately high rate of alcohol use disorder. Excess alcohol consumption is widespread in Native American communities. Native Americans use and misuse alcohol and other illicit substances at younger ages, and at higher rates, than that of all other ethnic groups. Consequently, their age-adjusted alcohol-related mortality rate is 5.3 times greater than the general population. The Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's National Household Survey on Drug Abuse reported the following for 1997: 19.8 percent of Native Americans ages 12 and older reported using illegal drugs that year, compared with 11.9 percent for the total U.S. population. Native Americans had the highest prevalence rates of marijuana and cocaine use, in addition to the need for drug abuse treatment.

Tribal governments have long prohibited the sale of alcohol on reservations, but generally, it is readily for sale in nearby border towns, and off-reservation businesses and states gain income from the business. As an example, in 2010, beer sales at off-reservation outlets in Whiteclay, Nebraska generated $413,932 that year in federal and sales taxes. Their customers are overwhelmingly Lakota from the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

Acknowledging that prohibition has not worked, in a major change in strategy since the late 20th century, as of 2007, 63 percent of the federally recognized tribes in the lower 48 states had legalized alcohol sales on their reservations. Among these, all the other tribes in South Dakota have legalized sales, as have many in Nebraska. The tribes decided to retain the revenues that previously would go to the states through retail sales taxes on this commodity. Legalizing the sales enables the tribes to keep more money within their reservation economies and support new businesses and services, as well as to directly regulate, police and control alcohol sales. The retained revenues enable them to provide health care and build facilities to better treat individuals and families suffering from alcohol use disorder. In some cases, legalization of alcohol sales also supported the development of resorts and casinos, to generate revenues for other economic enterprises.

Consequences of alcohol use disorder

Native Americans and Whites have the highest rates of Driving Under the Influence (DUI). A 2007 study conducted by the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) reports that 13.3% of Native Americans report past-year DUI.

Of 1660 people from seven Native American tribes, the lifetime prevalence of alcohol dependence ranged from 21%–56% for men and 17%–30% for women among all tribes. Physical and sexual abuse significantly increased the chances of alcohol dependence for men. Sexual abuse and boarding school attendance increased the odds of alcohol dependence among women. Native Americans, especially women, are at high risk for alcohol-related trauma, such as rape and assault.

Unintentional injuries due to alcohol use disorder

Unintentional injuries account for the third leading cause of death for Native Americans and the leading cause of death for Native Americans under 44 years old. Unintentional injuries include motor vehicle crashes, pedestrian-related motor vehicle crashes, drowning, and fire-related injuries. From 1985 to 1996, 1,484 Native American children died in motor vehicle crashes, which is twice the rate for white children.

National estimates of alcohol-related motor vehicle deaths show that Native Americans have a 250% higher death rate compared to the US population.

Cancer

Studies have indicated that there are fewer cases of cancer in Native Americans than other ethnic groups. However, cancer is prevalent in Native Alaskan women and Native American women as the leading and second leading cause of death, respectively. Death rates are 70% of that for whites, indicating that the ratio of death by cancer to new cancer cases is the highest for Native Americans compared to other ethnic groups. Women have been diagnosed with later-stage breast and cervical cancer. Native Indian and Alaska Native people are disproportionately prone to colon and lung cancer. In some communities, this is consistent with a high prevalence of risk factors such as smoking.

One research about the Pacific Northwest Native Americans found that there were many misidentified rates of cancer between 1996 and 1997. This misclassification was due to a low Native American blood quantum, resulting in an over-reported amount of Native Americans diagnosed with cancer. Because the research took data from the Oregon State Cancer Registry, the Washington State Cancer Registry, and the Cancer Data Registry of Idaho to research tribes in the respected states, their findings show that cancer rates among tribes in the US are heterogeneous.

However, data collected from cancer cases are limited. Regardless, experts have suggested that Native Americans experience cancer differently than other ethnic groups. This can be due to genetic risk factors, late detection of cancer, poor compliance with recommended treatment, the presence of concomitant disease, and lack of timely access to diagnostic and/or treatment methods. According to researchers, addressing underlying risk factors and low screening rates by implementing aggressive screening programs can prevent cancer from forming in Native Indian and Alaska Native communities.

Diabetes

Native Americans have some of the highest rates of diabetes in the world, specifically Type 2 diabetes. Although mostly diagnosed in adults, children are increasingly being diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes as well. Type 2 diabetes may be manageable through healthy eating, exercising, oral medication, or insulin injections.

A study published in Environmental Health Perspectives found that the prevalence of diabetes found in Native Americans of the Mohawk Nation was 20.2% due to traces of pesticides in food sources, where elevated serum PCBs, DDE, and HBC were associated. Mirex did not have a connection.

There is some recent epidemiological evidence that diabetes in the Native American population may be exacerbated by a high prevalence of suboptimal sleep duration.

Major cardiovascular disease

Heart disease accounts for the number one cause of death among Native Americans, causing them to have twice the rate of cardiovascular disease than the US population. High rates of diabetes, high blood pressure, and risk factors (unhealthy eating and sedentary lifestyle) contribute to the increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

Mental health

Native Americans are at high risk for mental disorders. The most prevalent concerns due to mental health include substance abuse, suicide, depression, anxiety, and violence. High rates of homelessness, incarceration, alcohol and substance use disorders, and stress and trauma in Native American communities might attribute to the risk. According to The Surgeon General's report, the U.S. mental health system is not equipped to meet the needs of Native Americans. Moreover, the budget constraints of the Indian Health Service allows only basic psychiatric emergency care.

Suicide

Suicide is a major public health problem for American Indians in the United States.

Prevalence of suicide among Native Americans

The Suicide rate for American Indians and Alaskan Natives is approximately 190% of the rate for the general population. Among American Indians/Alaska Natives aged 10 to 34 years suicide is the second leading cause of death with suicide ranked as the eighth leading cause of death for American Indians/Alaska Natives of all ages

Youth who have experienced life stressors are disproportionately affected by risky behaviors and at greater risk for suicide ideation. Suicide rates among American Indians and Alaska Natives youth are higher than those for other populations. The rate of suicide for American Indian/Alaskan Natives is 70% higher than for that of the general population and youth between age 10 and 24 are the most at risk.

College students are also among those most at risk for suicide; select data from the National College Health Association National College Health Assessment (ACHA-NCHA) found that approximately 15% of American Indian students reported seriously contemplating suicide over the past 12 months, compared with 9.1% of non-American Indian students; 5.7% of American Indian students reported attempting suicide, compared with 1.2% of non-American Indian students.

Suicide prevention

Prevention aims at halting or stopping the development of individual or social problem which is already evident. Prevention is different from intervention and treatment in that it is aimed at general population groups or individuals with various levels of risk. Prevention's goal is to reduce risk factors and enhance protective factors. Suicide prevention is a collective effort of organizations, communities, and mental health practitioners to reduce the incidence of suicide. Social workers have an important role to play in suicide prevention. Social workers are the largest occupational group of mental health professionals in the US, thus they play a significant role in the national approach to preventing suicide. The social work approach to suicide prevention among Native Americans identifies and addresses the individual's immediate clinical needs, community/environmental influences, and societal risk factors.

Possible programs to improve native health disparities

Indian Health Service

The Indian Health Service (IHS) was established within the Public Health Service in 1955 to meet federal treaty obligations to provide health services to members of federally recognized American Indian and Alaska Native tribes. The IHS consists of three branches of service: the federally operated direct care system, independent tribally operated health care services, and urban Indian health care services.

Affordable Care Act

In addition to the Indian Health Services, researchers have data suggesting that the Affordable Care Act supplements Native American healthcare. With the two services, tribes have greater flexibility in health care availability. Tribes have direct access to IHS funds, which can be administered via contracts and other arrangements made with providers. However, it alters trust relationships. The Affordable Care Act provides an opportunity for uninsured adults to gain Medicaid coverage. Although half of the uninsured adults are white, increases in coverage expand to all races to substantially reduce racial gaps in health insurance coverage. With new outreach and enrollment efforts, streamlined enrollment systems, penalties for not having health insurance coverage, the availability of newly created health insurance exchanges, and the expectation under the ACA that everyone will have insurance coverage, enrollment in Medicaid will increase in low-income communities.

The Indian Health Care Improvement Act, which is part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, does not guarantee a health care arrangement of the kind Americans have generally come to expect—namely, comprehensive inpatient and outpatient services available on the basis of need— a critical point when considering the IHS, which is often mistaken for a Native American health insurance program. According to the governor of the Pueblo of Tesuque Mark Mitchell, IHS does not cover everything that insurance does. It is not an entitlement program, unlike Medicare or Medicaid. The IHS is a series of direct health care services provided at IHS facilities. A key distinction between IHS health services and insurance concerns the policy framework and logic of budgeting that underpins them.

This produces a fundamentally different dynamic than that which drives programs such as Medicare or Medicaid, or especially private managed care plans. The IHS does what it can with the resources it is provided by Congress but is not obligated to provide the services required to meet the broader health needs of Native Americans in the pursuit of measurable outcomes.

The Oregon Experiment

In 2008, Oregon initiated Medicaid to 10,000 of a randomized 90,000 low-income, uninsured adults to participate in what is now known as the Oregon Medicaid health experiment. Within 4 study groups of one study, researchers observed that use of primary care services will increase, as more individuals will begin and continue to use medical care. The study was limited to the Portland metropolitan area. Researchers concluded that investment in primary care could help attend and mitigate the health care needs of individuals.

Food Insecurity

While research into Native American food security has gone unnoticed and under researched until recent years, studies are being conducted which reveal that Native Americans often times experience higher rates of food insecurity than any other racial group in the United States. The studies do not focus on the overall picture of Native American households and tend to focus on smaller sample sizes in the available research. In a study that evaluated the level of food insecurity among White, Asian, Black, Hispanic and Indigenous Americans: it was reported that over a 10-year span of 2000-2010, Indigenous people were reported to be one of the highest at-risk groups of from a lack of access to adequate food, reporting anywhere from 20%-30% of households suffering from this type of insecurity. There are many reasons that contribute to the issue with the biggest being high food costs on or near reservations, lack of access to well-paying jobs, and predisposition to health issues relating to obesity and/or mental health.

Trauma

Trauma among Native Americans can be seen through historical and intergenerational trauma and can be directly related to the substance use disorder and high rates of suicide among American Indian populations.

Historical trauma

Historical trauma is described as collective emotional and psychological damage caused by traumatic events in a person's lifetime and across multiple generations according to Dr. Laurelle Myhra, an expert on Native American mental health. Native Americans experience historical trauma through the effects of colonization such as wars and battles with the U.S. military, assimilation, forced removal, and genocide. Outside of war and purposeful genocide, a senior lecturer on Native American literature and culture Dr. Carrie Sheffield maintains other causes are equally traumatic. She asserts that Native Americans experienced historical trauma through fatal epidemics, forced relocation to reservations, and the education of Native children at boarding schools. Even though many American Indians did not experience first hand traumatic events like the Wounded Knee Massacre, multiple generations are still affected by them. On December 29, 1890, over 200 Lakota were killed at Wounded Knee creek, South Dakota by U.S. soldiers. More than half were unarmed women and children. Unanswered pain from the Wounded Knee Massacre is still felt and has been related to present day substance abuse and violence. Experts of Native American trauma and mental health Theresa O'Nell and Tom Ball from the University of Oregon disprove the common misconception that historical trauma only occurs generations prior. They assert, contrastingly, that many current generations experienced trauma due to current violations of treaty obligations, land rights, racism, forcible relocation, and forced assimilation through federally-legislated boarding schools. In their interviews with Klamath and Umatilla tribal members, they observed intense emotional responses to recounted ancestral trauma. For them, one old woman weeped recounting the massacre of her grandmother's tribe, who was just a child at the time.

The loss of lands are also instrumental to the effect of historical trauma on Native Americans. Four-fifths of American Indian land was lost due to the Dawes Allotment Act of 1887. The U.S. government gave American Indian men sections of land and opened the “surplus" to white settlers and government interests. The psychological effects of the Dawes Allotment Act can be better appreciated when looking at American Indians relationship to the land, which is similar for all Indian tribes. Experts in Native American trauma and culture Braveheart-Jordan and DeBruyn propose the land is the origin of the people, who came out of the earth, and is the interdependent and spiritual link to all things. For the Klamath tribe in the Pacific Northwest, the land provided the resources and lessons necessary for the tribe's growth, so they hold a responsibility to respect and protect the land.

To understand the mechanism and impacts of historical trauma, a different understanding of time is often used. O'Nell and Bell interviewed members of the Klamath tribes and the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (CTUIR) and documented their experiences and stories to craft tribal genograms, a pictorial display of the tribe's psychology and history. At the end of their research, they were instructed by these tribes to draw the genogram in a circle as opposed to the traditional linear form. Additionally, they were instructed to start with creation and progress in the counterclockwise direction all to maintain the tribe's "spiritual truth." This was in order to not only connect the tribe's experiences and their psychological effects, but to interconnect the tribe's other networks like families, cultures, and spiritual beings.

Intergenerational trauma

American Indian youth are confronted with the burden of intergenerational trauma, trauma that is passed between generations by historical or cultural trauma. A study looking at two generations of American Indians and their relationship to psychological trauma found that participants who experienced traumatic events early in their lives usually abused substances to cope. Use of illicit substances and excessive consumption of alcohol are unhealthy coping mechanisms that many Native Americans learn to use at a young age by observing parental practices. Often youth begin to take on these traumas and can misuse alcohol and drugs to the point of death in some cases. This can contribute to American Indian adolescents exceeding the national average for alcohol and drug related deaths; being 1.4 and 13.3 times higher. Peter Menzies, the clinical head of Aboriginal Services at the Center for Addictions and Mental Health in Toronto, also proposes that government-sanctioned boarding schools are a key proponent of intergenerational trauma for Native Americans. He claims that former students adopted parenting methods like corporal punishment and loud berating tactics which then traumatize the children in a similar way. Additionally, Dr. Sheffield suggests that Native Americans experience a degree of intergenerational cultural trauma. According to Sheffield, the United States is a collection of "settler colonies" where the colonizers have not left. Therefore, the European-influenced culture grew to dominate the existing Native American culture with offensive representations like a "savage" and a "dying breed." These influences, according to Sheffield, collectively lead to the loss of cultural cohesion in the Native American community.

Boarding school

Many American Indians were forcibly assimilated into American culture after being abducted from reservations through boarding schools that were designed to 'civilize' them. "Kill the Indian and save the man" was the motto and belief. Some documented practices to assimilate children at these boarding schools included shaving of children's hair, corporal punishments for speaking in native languages, manual labor to sustain the campus facilities, and intense daily regimentation. A less documented practice includes the use of DDT and kerosene in children's hair upon arrival to the boarding schools. Boarding schools were often packed with children to gain more grant money, and became centers for diseases such as trachoma and tuberculosis. Due to general inefficiency in handling outbreaks of diseases, many native children died at the boarding schools, often without having their parents notified or having been able to contact any family.

Experts on Native American trauma support that boarding schools were a key proponent of intergenerational trauma. Former students who survived the schools turned towards alcohol and illicit drugs to cope with the trauma. These coping methods were then passed on to their children since they seemed like acceptable means of handling trauma. These former students also use similar parenting practices they received at boarding school on their own children. As explained by Menzies, the trauma suffered by these former students is continued into their children's generation through parental methods and modeled substance abuse. Menzies furthers that because the former students abused substances to cope with their trauma of boarding school, the children of these students cope with this trauma the same way.

In response to the psychological and intergenerational trauma caused, the National Boarding School Healing Project (NBSHP) was launched as a partnership to document these experiences and their effects on Native Americans. When some participants were asked about potential healing methods to their trauma, they suggested that communities in general should return to traditional Native American spiritual practices while former students of boarding schools specifically should attempt forgiveness to release internal turmoil and hatred.

Solutions

Many researchers, psychologists, counselors, and social workers are calling for culturally competent practitioners as well as using culturally appropriate practices when working with American Indian clients. The Wellbriety Movement creates a space for American Indians to learn how to reconnect with their culture by using culturally specific principles to become and remain sober. Some examples are burning sage, cedar, and sweetgrass as a means to cleanse physical and spiritual spaces, verbally saying prayers and singing in one's own tribal language, and participating in tribal drum groups and ceremonies as part of meetings and gatherings. Dr. Michael T. Garrett, an assistant professor of counsel education at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, proposes that psychologists must adopt mental-health practices that cultivate Native American values rather than conflicting contemporary mainstream American ideals. Some of these views include interconnectedness of the mind, body, and soul, the connection between humanity and nature, internal self-discipline, and appreciation of the present while the future is received in its own time. These are partly in response to the varied degrees of acculturation Native American individuals present. Garrett describes some possible degrees of acculturation: "marginal" where Native Americans may speak English with their native language and do not identify totally with neither mainstream American ideals or tribal customs or "assimilated" where Native American individuals have embraced mainstream American ideals and renounced their tribal familial connections.

Additional solutions, as proposed by the Klamath tribe, are government restoration of land rights and the following of past treaty obligations. They propose that the restoration of tribal recognition by the federal government has partly healed their historical trauma. They maintain, however, that intergenerational trauma will not be healed until their traditional relationship to the land is restored in order to ground the tribe's "immortal connections" back to their place in the world. For the Klamath tribes, another solution is to constantly remember their history through their counter narrative rather than through the dominant narrative of non-Native oppressors in order to preserve the tribe's formerly oppressed spirit.