The Living Constitution, or judicial pragmatism, is the viewpoint that the United States Constitution holds a dynamic meaning that evolves and adapts to new circumstances even if the document is not formally amended. The Constitution is said to develop alongside society's needs and provide a more malleable tool for governments. The idea is associated with views that contemporary society should be considered in the constitutional interpretation of phrases. The Constitution is referred to as the living law of the land as it is transformed according to necessities of the time and the situation. Some supporters of the living method of interpretation, such as professors Michael Kammen and Bruce Ackerman, refer to themselves as organists.

The arguments for the Living Constitution vary but can generally be broken into two categories. First, the pragmatist view contends that interpreting the Constitution in accordance with its original meaning or intent is sometimes unacceptable as a policy matter and so an evolving interpretation is necessary. The second, relating to intent, contends that the constitutional framers specifically wrote the Constitution in broad and flexible terms to create such a dynamic, "living" document.

Opponents often argue that the Constitution should be changed by an amendment process because allowing judges to change the Constitution's meaning undermines democracy. Another argument against the Living Constitution is that legislative action, rather than judicial decisions, better represent the will of the people in the United States in a constitutional republic, since periodic elections allow individuals to vote on who will represent them in the United States Congress, and members of Congress should (in theory) be responsive to the views of their constituents. The primary alternative to a living constitution theory is "originalism." Opponents of the Living Constitution often regard it as a form of judicial activism.

History

During the Progressive Era, many initiatives were promoted and fought for but prevented from full fruition by legislative bodies or judicial proceedings. One case in particular, Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co., enraged early progressive activists hoping to achieve an income tax. That led progressives to the belief that the Constitution was unamendable and ultimately for them to find a new way to achieve the desired level of progress. Other proposals were considered, such as making the amending formula easier.

Origins

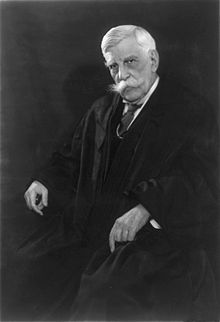

The phrase originally derives from the title of a 1927 book of that name by Professor Howard Lee McBain, and early efforts at developing the concept in its modern form have been credited to figures like Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., Louis D. Brandeis, and Woodrow Wilson. The earliest mentions of the Constitution as "living," particularly in the context of a new way of interpreting it, comes from Woodrow Wilson's book Constitutional Government in the United States in which he wrote:

Living political constitutions must be Darwinian in structure and in practice.

Wilson strengthened that view, at least publicly, while he campaigned for president in 1912:

Society is a living organism and must obey the laws of life, not of mechanics; it must develop. All that progressives ask or desire is permission - in an era when "development," "evolution," is the scientific word - to interpret the Constitution according to the Darwinian principle; all they ask is recognition of the fact that a nation is a living thing and not a machine.

Judicial pragmatism

Although the "Living Constitution" is itself a characterization, rather than a specific method of interpretation, the phrase is associated with various non-originalist theories of interpretation, most commonly judicial pragmatism. In the course of his judgment in Missouri v. Holland 252 U.S. 416 (1920), Holmes remarked on the Constitution's nature:

With regard to that we may add that when we are dealing with words that also are a constituent act, like the Constitution of the United States, we must realize that they have called into life a being the development of which could not have been foreseen completely by the most gifted of its begetters. It was enough for them to realize or to hope that they had created an organism; it has taken a century and has cost their successors much sweat and blood to prove that they created a nation. The case before us must be considered in the light of our whole experience and not merely in that of what was said a hundred years ago. The treaty in question does not contravene any prohibitory words to be found in the Constitution. The only question is whether [252 U.S. 416, 434] it is forbidden by some invisible radiation from the general terms of the Tenth Amendment. We must consider what this country has become in deciding what that amendment has reserved.

According to the pragmatist view, the Constitution should be seen as evolving over time as a matter of social necessity. Looking solely to original meaning, which would largely permit many practices that are now universally condemned, thus causes the rejection of pure originalism out of hand.

That general view has been expressed by Judge Richard Posner:

A constitution that did not invalidate so offensive, oppressive, probably undemocratic, and sectarian law [as the Connecticut law banning contraceptives] would stand revealed as containing major gaps. Maybe that is the nature of our, or perhaps any, written Constitution; but yet, perhaps the courts are authorized to plug at least the most glaring gaps. Does anyone really believe, in his heart of hearts, that the Constitution should be interpreted so literally as to authorize every conceivable law that would not violate a specific constitutional clause? This would mean that a state could require everyone to marry, or to have intercourse at least once a month, or it could take away every couple's second child and place it in a foster home.... We find it reassuring to think that the courts stand between us and legislative tyranny even if a particular form of tyranny was not foreseen and expressly forbidden by framers of the Constitution.

The pragmatist objection is central to the idea that the Constitution should be seen as a living document. Under that view, for example, constitutional requirements of "equal rights" should be read with regard to current standards of equality, not those of decades or centuries ago, an alternative that would be unacceptable.

Original intent

In addition to pragmatist arguments, most proponents of the living Constitution argue that the Constitution was deliberately written to be broad and flexible to accommodate social or technological change over time. Edmund Randolph, in his Draft Sketch of Constitution, wrote:

In the draught of a fundamental constitution, two things deserve attention:

- 1. To insert essential principles only; lest the operations of government should be clogged by rendering those provisions permanent and unalterable, which ought to be accommodated to times and events: and

- 2. To use simple and precise language, and general propositions, according to the example of the constitutions of the several states.

The doctrine's proponents assert that Randolph's injunction to use "simple and precise language, and general propositions," such that the Constitution could "be accommodated to times and events," is evidence of the "genius" of its framers.

James Madison, the principal author of the Constitution and often called the "Father of the Constitution," said this in argument for original intent and against changing the Constitution by evolving language:

I entirely concur in the propriety of resorting to the sense in which the Constitution was accepted and ratified by the nation. In that sense alone it is the legitimate Constitution. And if that is not the guide in expounding it, there may be no security for a consistent and stable, more than for a faithful exercise of its powers. If the meaning of the text be sought in the changeable meaning of the words composing it, it is evident that the shape and attributes of the Government must partake of the changes to which the words and phrases of all living languages are constantly subject. What a metamorphosis would be produced in the code of law if all its ancient phraseology were to be taken in its modern sense.

Some Living Constitutionists seek to reconcile themselves with the originalist view, which interprets the Constitution based on its original meaning.

Application

One application of the Living Constitution's framework is seen in the Supreme Court's reference to "evolving standards of decency" under the Eighth Amendment, as was seen in the 1958 Supreme Court case of Trop v. Dulles:

[T]he words of the [Eighth] Amendment are not precise, and that their scope is not static. The Amendment must draw its meaning from the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society.

The Court referred in Trop only to the Eighth Amendment's prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment, but its underlying conception was that the Constitution is written in broad terms and that the Court's interpretation of those terms should reflect current societal conditions, which is the heart of the Living Constitution.

Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses

From its inception, one of the most controversial aspects of the living constitutional framework has been its association with broad interpretations of the Equal Protection Clause and the Due Process Clause of the Fifth and the Fourteenth Amendments.

Proponents of the Living Constitution suggest that a dynamic view of civil liberties is vital to the continuing effectiveness of the constitutional scheme. It is now seen as unacceptable to suggest that married women or descendants of slaves are not entitled to liberty or equal protection with regard to coverture laws, slavery laws, and their legacy, as they were not expressly seen as free from such by those who ratified the Constitution. Advocates of the Living Constitution believe that the framers never intended their 18th-century practices to be regarded as the permanent standard for those ideals.

Living Constitutionalists suggest that broad ideals such as "liberty" and "equal protection" were included in the Constitution precisely because they are timeless and for their inherently dynamic nature. Liberty in 1791 is argued to have never been thought to be the same as liberty in 1591 or in 1991, but it was rather seen as a principle transcending the recognized rights of the day and age. Giving them a fixed and static meaning in the name of "originalism" is thus said to violate the very theory that it purports to uphold.

Points of contention

As the subject of significant controversy, the idea of a Living Constitution is plagued by numerous conflicting contentions.

Disregard of constitutional language

The idea of a Living Constitution was often characterized by Justice Scalia and others as inherently disregarding constitutional language and as suggesting that one should not simply read and apply the constitutional text.

Jack Balkin argues that was not the intended meaning of the term, however, and suggests that the Constitution be read contemporaneously, rather than historically. Such an inquiry often consults the original meaning or intent, along with other interpretive devices. A proper application then involves some reconciliation between the various devices, not a simple disregard for one or another.

Judicial activism

Another common view of the Living Constitution is as synonymous with "judicial activism," a phrase that is generally used to accuse judges of resolving cases based on their own political convictions or preferences.

Comparisons

It may be noted that the Living Constitution does not itself represent a detailed philosophy and that distinguishing it from other theories can be difficult. Indeed, supporters often suggest that it is the true originalist philosophy, but originalists generally agree that phrases such as "just compensation" should be applied differently than 200 years ago. It has been suggested that the true difference between the judicial philosophies regards not meaning at all but rather the correct application of constitutional principles. A supporter of the Living Constitution would not necessarily state, for instance, that the meaning of "liberty" has changed since 1791, but it may be what it has always been, a general principle that recognizes individual freedom. The important change might be in what is recognized as liberty today but was not fully recognized two centuries ago. That view was enunciated for the Supreme Court by Justice George Sutherland in 1926:

[W]hile the meaning of constitutional guaranties never varies, the scope of their application must expand or contract to meet the new and different conditions which are constantly coming within the field of their operation. In a changing world it is impossible that it should be otherwise. But although a degree of elasticity is thus imparted, not to the meaning, but to the application of constitutional principles, statutes and ordinances, which, after giving due weight to the new conditions, are found clearly not to conform to the Constitution, of course, must fall.

To complete the example, the question of how to apply a term like "liberty" may not be a question of what it "means" but rather a question of which liberties are now entitled to constitutional protection. Supporters of a Living Constitution tend to advocate a broad application in accordance with current views, and originalists tend to seek an application consistent with views at the time of ratification. Critics of the Living Constitution assert that it is more open to judicial manipulation, but proponents argue that theoretical flexibility in either view provides adherents extensive leeway in what decision to reach in a particular case.

Debate

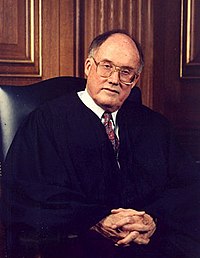

By its nature, the "Living Constitution" is not held to be a specific theory of construction but a vision of a Constitution whose boundaries are dynamic and congruent with the needs of society as it changes. That vision has its critics; in the description of Chief Justice William Rehnquist, it "has about it a teasing imprecision that makes it a coat of many colors."

It is important to note that the term "Living Constitution" is sometimes used by critics as a pejorative, but some advocates of the general philosophy avoid the term. Opponents of the doctrine tend to use the term as an epithet synonymous with "judicial activism" (itself a hotly-debated phrase). However, just as some conservative theorists have embraced the term Constitution in Exile, which similarly gained popularity through use by liberal critics, textualism was a term that had pejorative connotations before its widespread acceptance as a badge of honor. Some liberal theorists have embraced the image of a living document as appealing.

Support

One argument in support of the concept of a "Living Constitution" is the concept that the Constitution itself is silent on the matter of constitutional interpretation. Proponents assert that the Constitution's framers, most of whom were trained lawyers and legal theorists, were certainly aware of the debates and would have known the confusion that not providing a clear interpretive method would cause. If the framers had meant for future generations to interpret the Constitution in a specific manner, they could have indicated such within the Constitution itself. The lack of guidance within the text of the Constitution suggests that there was no such consensus, or the framers never intended any fixed method of constitutional interpretation.

Relating to the pragmatic argument, it is further argued that if judges were denied the opportunity to reflect on changes to modern society in interpreting the scope of constitutional rights, the resulting Constitution either would not reflect the current mores and values or would require a constant amendment process to reflect the changing society.

Another defense of the Living Constitution is based in viewing the Constitution not merely as law but also as a source of foundational concepts for the governing of society. Of course, laws must be fixed and clear so that people can understand and abide by them on a daily basis. However, if the Constitution is more than a set of laws but also provides guiding concepts, which will in turn provide the foundations for laws, the costs and benefits of such an entirely-fixed meaning are very different. The reason is simple: if a society locks itself into a previous generation's interpretive ideas, it will wind up either constantly attempting to change the Constitution to reflect changes or simply scrapping the Constitution altogether. While the rights and powers provided in the Constitution remain, the scope that those rights and powers should account for society's present experiences. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., wrote in 1914: "Provisions of the Constitution of the United States are not mathematical formulas having their essence in their form, but are organic living institutions transplanted from English soil. Their significance is not to be gathered simply from the words and a dictionary, but by considering their origin and the line of their growth."

A prominent endorsement of the Living Constitution concept was heard during the 2000 presidential campaign by the Democratic candidate, Al Gore.

Opposition

A common argument against the doctrine of a "Living Constitution" comes not from its moderate use but the concept being seen as promoting activism. The term presumes the premise of that what is written is insufficient in the light of what has happened since. The more moderate concept is generally not the target of those who are against the Living Constitution. The concept considered perverse by constructionalists is making the law say what is desired, rather than submitting to what it actually says.

Economist Thomas Sowell argues in his book Knowledge and Decisions that since the Constitution's original designers provided for the means of amending it, they never intended for their original words to change meaning. Sowell also points out cases in which arguments are made that the original framers never considered certain issues, although a clear record of them doing so exists.

Another argument against is similar to the argument for it: the fact that the Constitution itself is silent on the matter of constitutional interpretation. The Living Constitution is a doctrine that relies on the concept that the original framers could not come to a consensus about how to interpret or never intended any fixed method of interpretation. That would then allow future generations the freedom to reexamine for themselves how to interpret it. This view does not take into account why the original constitution does not allow for judicial interpretation in any form. The Supreme Court's power for constitutional review, and by extension its interpretation, was not formalized until Marbury v. Madison in 1803. Thus, the argument therefore relies on an argument that had no validity when the constitution was actually written.

The views of the constitutional law scholar Laurence Tribe are often described by conservative critics such as Robert Bork as being characteristic of the Living Constitution paradigm. Bork labeled Tribe's approach as "protean", since it was whatever Tribe needed it to be to reach a desired policy outcome. Tribe rejected both the term and the description. Such a construction appears to define the doctrine as being an ends dictate the means anti-law philosophy. Some liberal constitutional scholars have since implied a similar charge of intellectual dishonesty regarding originalists by noting that they virtually never reach outcomes with which they disagree. (Many academic political scientists believe that justices and appeals judges are willing to alter their outcomes to attain philosophical majorities on certain questions.)

In 1987, Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall delivered a lecture, "The Constitution: A Living Document," in which he argued that the Constitution must be interpreted in light of the moral, political, and cultural climate of the age of interpretation. If Bork's formulation of "the living Constitution" is guiding, any constitutional interpretation other than originalism of one form or another implies the Living Constitution. If, however, Marshall's formulation is guiding, it is unclear whether methods derived from law and economics or the Moral Constitution might be implicated.

References to the Living Constitution are relatively rare among legal academics and judges, who generally prefer to use language that is specific and less rhetorical. It is also worth noting that there is disagreement among the opponents of the doctrine on whether the idea is the same as, implied by, or assumed by judicial activism, which has a similar ambiguity of meaning and is also used primarily as a derogatory epithet.

Justice Clarence Thomas has routinely castigated "living Constitution" doctrine. In one particularly strongly-worded attack, he noted:

Let me put it this way; there are really only two ways to interpret the Constitution – try to discern as best we can what the framers intended or make it up. No matter how ingenious, imaginative or artfully put, unless interpretive methodologies are tied to the original intent of the framers, they have no more basis in the Constitution than the latest football scores. To be sure, even the most conscientious effort to adhere to the original intent of the framers of our Constitution is flawed, as all methodologies and human institutions are; but at least originalism has the advantage of being legitimate and, I might add, impartial.

Justice Antonin Scalia expressed similar sentiments and commented:

[There's] the argument of flexibility and it goes something like this: The Constitution is over 200 years old and societies change. It has to change with society, like a living organism, or it will become brittle and break. But you would have to be an idiot to believe that; the Constitution is not a living organism; it is a legal document. It says something and doesn't say other things.... [Proponents of the living constitution want matters to be decided] not by the people, but by the justices of the Supreme Court .... They are not looking for legal flexibility, they are looking for rigidity, whether it's the right to abortion or the right to homosexual activity, they want that right to be embedded from coast to coast and to be unchangeable.

He also said:

If you think aficionados of a living Constitution want to bring you flexibility, think again.... You think the death penalty is a good idea? Under the formalist understanding of the Constitution, but not under the Living Constitution understanding, you can persuade your fellow citizens to adopt it. You want a right to abortion? Persuade your fellow citizens and enact it. That's flexibility.

Professor Michael Ramsey has criticized living constitutionalism on the grounds that there are very few limits on what it could achieve. Ramsey uses Kenneth Jost's argument in favor of the unconstitutionality of the electoral college to argue that a living constitutionalist could believe, "Even something expressly set forth in the Constitution can be unconstitutional if annoying, inconvenient or ill-advised." Likewise, Professors Nelson Lund and John McGinnis have argued that it would be difficult for a living constitutionalist such as Robert Post to object if the US Supreme Court had used its reverse incorporation principle together with the principles of Reynolds v. Sims to make the US cte apportioned exclusively based on population and still retained the trust of the American people after doing so.

Judicial activism

One accusation made against the living Constitution method states that judges that adhere to it are judicial activists and seek to legislate from the bench. That generally means that a judge winds up substituting his judgment on the validity, meaning, or scope of a law for that of the democratically-elected legislature.

Adherents of the Living Constitution are often accused of "reading rights" into the Constitution and of claiming that the Constitution implies rights that are not found in its text. For example, in Roe v. Wade, the US Supreme Court held that the Constitution has an implicit "right to privacy," which extends to a woman's right to decide to have an abortion. As such, the Court held that the government can regulate that right with a compelling interest and only if the regulation is as minimally intrusive as possible. Conservative critics have accused the Supreme Court of activism in inventing a constitutional right to abortion. That accusation is accurate in that abortion rights indeed had not been recognized but, the accusation has been applied selectively. For example, few conservatives levy the same claim against the Supreme Court for its decisions concerning sovereign immunity, a term that was also found to be implicit in the Eleventh Amendment by the Supreme Court.

Outside the United States

Canada

In Canada, the living constitution is described under the living tree doctrine.

Unlike in the United States, the fact that the Canadian Constitution was intended from the outset to encompass unwritten conventions and legal principles is beyond question. For example, the text of the original constitution does not mention the office of Prime Minister and still fails to state that the Governor General always grants royal assent to bills. Principles such as democracy, the implied Bill of Rights, the rule of law, and judicial independence are held to derive in part from the preamble of the constitution, which declared the Canadian Constitution to be "similar in principle" to the British Constitution.

The concept of an evolving constitution has notably been applied to determine the division of powers between provinces and the federal government in areas of jurisdiction that were not contemplated at the time of enactment of the British North America Act. For example, authority over broadcasting has been held to fall within the federal "peace, order and good government" power.

The Supreme Court of Canada, in Re: Same-Sex Marriage (2004), held that the Canadian Parliament, as opposed to provincial legislatures, had the power to define marriage as including same-sex unions. It rejected claims that the constitutionally-enumerated federal authority in matters of "Marriage and Divorce" could not include same-sex marriage because the notion had not been conceived in 1867:

The "frozen concepts" reasoning runs contrary to one of the most fundamental principles of Canadian constitutional interpretation: that our Constitution is a living tree which, by way of progressive interpretation, accommodates and addresses the realities of modern life.

United Kingdom

It has been argued that a primary determinative factor in whether a legal system will develop a "living constitutional" framework is the ease with which constitutional amendments can be passed. With that view in mind, the British constitution could be considered a "living constitution" and requires only a simple majority vote to amend. It is also important to note that the British constitution not derive from a single written document. Therefore, its dependence on the important role of statute law and the influence of its own version of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom also make it a living constitution. For instance, after the World War II, human-rights based philosophy also became profoundly influential in creating a new international legal order, which the United Kingdom conformed with. It is also important to note the different levels to which the United Kingdom and the United States hold a living constitution, with the United States still referring to an original document that quite contrasts the United Kingdom's unwritten document.

India

The Constitution of India is considered to be a living and breathing document.