American electoral politics have been dominated by two major political parties since shortly after the founding of the republic of the United States of America. Since the 1850s, the two have been the Democratic Party and the Republican Party—one of which has won every United States presidential election since 1852 and controlled the United States Congress since at least 1856. Despite keeping the same names, the two parties have both evolved in terms of ideologies, positions, and support bases over their long lifespans, in response to social, cultural, and economic developments—the Democratic Party being the left-of-center party since the time of the New Deal, and the Republican Party now being the right-of-center party.

Political parties are not mentioned in the U.S. Constitution (which predates the party system). The two-party system is based on laws, party rules and custom. Several third parties also operate in the U.S., and from time to time elect someone to local office. Some of the larger ones include the Constitution, Green, Alliance, and Libertarian parties, with the latter being the largest third party since the 1980s. A small number of members of the US Congress, a larger number of political candidates, and a good many voters (35-45%) have no party affiliation. However, most self-described independents consistently support one of the two major parties when it comes time to vote, and members of Congress with no political party affiliation caucus (meet to pursue common legislative objectives) with either the Democrats or Republicans.

The need to win popular support in a republic led to the American invention of voter-based political parties in the 1790s. Americans were especially innovative in devising new campaign techniques that linked public opinion with public policy through the party. Political scientists and historians have divided the development of America's two-party system into six or so eras or "party systems", starting with the Federalist Party, which supported the ratification of the Constitution, and the Democratic-Republican Party or the Anti-Administration party (Anti-Federalists), which opposed a powerful central government.

History and political eras

- Founding fathers

The United States Constitution is silent on the subject of political parties. The Founding Fathers did not originally intend for American politics to be partisan. In Federalist Papers No. 9 and No. 10, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, respectively, wrote specifically about the dangers of domestic political factions. In addition, the first President of the United States, George Washington, was not a member of any political party at the time of his election or throughout his tenure as president. Furthermore, he hoped that political parties would not be formed, fearing conflict and stagnation, as outlined in his Farewell Address. The Founders “did not believe in parties as such, scorned those that they were conscious of as historical models, had a keen terror of party spirit and its evil consequences," but Richard Hofstadter wrote, "almost as soon as their national government was in operation, found it necessary to establish parties.”

In the past 150-plus years the two dominant parties have changed their ideologies and bases of support considerably, while maintaining their names. The Democratic party, that in the aftermath of the Civil War was an agrarian pro-states-rights, anti-civil rights, pro-easy money, anti-tariff, anti-bank, coalition of Jim Crow "Solid South", Western small farmers, along with budding labor unions and Catholic immigrants; has evolved into what is as of 2020, a strongly pro-civil rights party, disproportionately composed of women, LGBT, union members, and urban, educated, younger, non-white voters. Over the same period, the Republican Party has gone from being the dominant American "Grand Old Party" of business large and small, skilled craftsmen, clerks, professionals and freed African Americans, based especially in the industrial northeast; to a right-wing, disproportionately composed of family businesses, less educated, older, rural, southern, religious, and white working class voters. Along with this realignment, political and ideological polarization has increased, norms have deteriorated, leading to greater tension and "deadlock" in attempts to pass ideologically controversial bills.

Some historians have divided the history of American political parties into about a half dozen "party systems."

First Party System: 1792–1824

The beginnings of the American two-party system emerged from George Washington's immediate circle of advisers, which included Alexander Hamilton and James Madison. Hamilton and Madison wrote the aforementioned Federalist Papers against political factions, but by the 1790s, different views of the new country's proper course had already developed, and those who held these opposing views tried to win support for their cause by banding together.

- The network of followers of Alexander Hamilton, the Hamiltonian faction, took up the name "Federalist"; they favored a strong central government that would support the interests of commerce and industry and close ties to Britain.

- The followers of Madison and Thomas Jefferson, the Jeffersonians and then the "Anti-Federalists," took up the name "Democratic-Republicans"; they preferred a decentralized agrarian republic in which the federal government had limited power.

The Jeffersonians came to power in 1800 and the Federalists were too elitist to compete effectively. The Federalists survived in the Northeast, but their refusal to support the War of 1812 verged on secession and was a devastating blow when the war ended well. The Era of Good Feelings under President James Monroe (1816–1824) marked the end of the First Party System and a brief period in which partisanship was minimal.

Second Party System: 1828–1854

By 1828, the Federalists had disappeared as an organization. Jackson's presidency split the Democratic-Republican Party — "Jacksonians" became the Democratic Party; those following the leadership of John Quincy Adams became the "National Republicans", (no connection to the later Republican Party that exists today). After the 1832 election, opponents of Jackson coalesced into the Whig Party. National Republicans, Anti-Masons and others joined the new party led by Henry Clay. The two party political system continued but with two different parties.

The early Democratic Party stood for individual rights and state rights, supported the primacy of the Presidency over the other branches of government, opposed banks (namely the Bank of the United States), high tariffs, as well as modernizing programs that they felt would build up industry at the expense of the farmers. It styled itself as the party of the "common man". Presidents Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren and James K. Polk, were all Democrats who defeated Whig candidates, but by narrow margins.

The Whigs, on the other hand, advocated the supremacy of Congress over the executive branch as well as policies of modernization and economic protectionism. Central political battles of this era were the Bank War and the Spoils system of federal patronage.

Jackson introduced the practice of "hosting barbecues and cultivating a national network of affiliates" and with his campaigns began the tradition of not just voting for a Democrat but identifying as a Democrat. "Parties were becoming a fixture not just in America’s politics but also in its social life."

In the 1850s, the issue of slavery took center stage, with disagreement in particular over the question of whether slavery should be permitted in the country's new territories in the West. The Whig Party attempted to straddle the issue with the Kansas–Nebraska Act, where the status of slavery would be decided based on "popular sovereignty", (i.e. the citizens of each territory, rather than Congress, would determine whether slavery would be allowed). Whigs sank to their death after the overwhelming electoral defeat by Franklin Pierce in the 1852 presidential election. Ex-Whigs joined the Know Nothings or the newly formed anti-slavery Republican Party. While the Know Nothing party was short-lived, Republicans would survive the intense politics leading up to the Civil War. The primary Republican policy was that slavery be excluded from all the territories. Just six years later, this new party captured the presidency when Abraham Lincoln won the election of 1860, the election that established the Democratic and Republican parties as the major parties of America.

Third Party System: 1854–1890s

The anti-slavery Republican Party emerged in 1854. It adopted many of the economic policies of the Whigs, such as national banks, railroads, high tariffs, homesteads and aid to land grant colleges.

After the defeat of the Confederacy, it became the dominant party in America for decades, associated with the successful military defense of the Union and often known as "the Grand Old Party". The Republican coalition consisted of businessmen, shop owners, skilled craftsmen, clerks, and professionals who were attracted to the party's modernization policies, and newly enfranchised African Americans (Freedmen).

The Democratic Party was usually in opposition during this period, although it often controlled the Senate or the House of Representatives, or both. The Democrats were known as "basically conservative and agrarian-oriented", and like the Republicans, it was a broad-based voting coalition. Their support came from "Redeemers" of the Jim Crow "Solid South" (i.e. solidly Democratic) where "repressive legislation and physical intimidation" prevented the "newly enfranchised African Americans from voting"; small farmers in the West (before the Sun belt boom, both regions being much less populated and politically powerful); there were also conservative pro-business Bourbon Democrats, traditional Democrats in the North (many of them former Copperheads), and Catholic immigrants, among others.

As the party of states' rights, post-Civil War Democrats opposed civil rights legislation. As the (sometimes) populist party of small farmers, it opposed the interests of big business, such as protective tariffs that raised prices on imported goods needed by rural people. The party favored cheap-money policies - low interest rates and inflation favoring those with substantial debts, such as small farmers.

Civil war and Reconstruction issues polarized the parties until the Compromise of 1877, which saw the withdrawal of the last federal troops from the Southern United States. (By 1905 most black people were effectively disenfranchised in every Southern state.)

During the post-civil war era of the nineteenth century, parties were well established as the country's dominant political organizations, and party allegiance had become an important part of most people's consciousness. Party loyalty was passed from fathers to sons, and in an era before motion pictures and radio, party activities, including spectacular campaign events, complete with uniformed marching groups and torchlight parades, were a part of the social life of many communities.

Fourth Party System: 1896–1932

1896 saw the beginning of the Progressive Era. The Republican Party still dominated and the interest groups and voting blocs were unchanged, but the central domestic issues changed to government regulation of railroads and large corporations ("trusts"), the protective tariff, the role of labor unions, child labor, the need for a new banking system, corruption in party politics, primary elections, direct election of senators, racial segregation, efficiency in government, women's suffrage, and control of immigration.

Some realignment took place, giving Republicans dominance in the industrial Northeast and new strength in the border states.

The era began after the Republicans blamed the Democrats for the Panic of 1893, which later resulted in William McKinley's victory over William Jennings Bryan in the 1896 presidential election.

Fifth Party System: 1932–1976

The disruption and suffering of the Great Depression (1929-1939) and the New Deal programs (1933–39) of Democrat president Franklin D. Roosevelt designed to deal with it, created a dramatic political shift. The Democrats were now the party of "big government"; the dominant party (retaining the presidency until 1952 and controlling both houses of Congress for most of the period from the 1930s to the mid-1990s); and positioned towards liberalism (while conservatives increasingly dominated the GOP).

The New Deal raised the minimum wage, established the Social Security and other federal services; Roosevelt "forged a broad coalition—including small farmers, Northern city dwellers with "urban political machines", organized labor, European immigrants, Catholics, Jews, African Americans, liberals, intellectuals, and reformers", but also the traditionally Democratic segregationist white Southerners.

Opposition Republicans were split between a conservative wing, led by Ohio Senator Robert A. Taft, and a more successful moderate wing exemplified by the politics of Northeastern leaders such as Nelson Rockefeller, Jacob Javits, and Henry Cabot Lodge. The latter steadily lost influence inside the GOP after 1964.

Sixth Party System, 1980s–2016

Around 1968 a breakup of the old Democratic Party New Deal coalition began and American politics became more polarized along ideology. Over the coming decades the blurred ideological character of American political party coalitions—where Democrats had a number of important elected office holders (mostly in the South) who were considerably more conservative than many important Republican senators and governors (for example Nelson Rockefeller)—dissipated. In time, not only did conservative Democrats and liberal Republicans retire, switch parties, or lose elections, so did centrists (Rudy Giuliani, George Pataki, Richard Riordan and Arnold Schwarzenegger).

Civil Rights legislation—the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965—driven by Democratic president Lyndon B. Johnson, along with Barry Goldwater's 1964 presidential campaign and president Richard M. Nixon's "Southern strategy"—began the breaking away of white segregationist Solid South from Democrats and over time created a solidly Republican south. Southern white voters started voting for Republican presidential candidates in the 1950s, and Republican state and local candidates in the 1990s.

Anti-Vietnam War protests alienated conservative Democrats from the protesters. The "religious right" emerged as a wing of the Republican Party—made up of Catholics and Evangelical Protestants (previously having nothing to do with each other but now) united in opposition to abortion and same-sex marriage. Also increasing political polarization was the trend towards replacing county caucuses and state conventions with political primaries, where the party core/base could "primary", (defeat in primary elections) moderate candidates who general election voters liked but the base did not.

Eventually a large majority of rural and working class whites nationwide became the base of the Republican Party; while the Democratic Party was increasingly made up of a coalition of African Americans, Latinos, and white urban progressives.

Whereas for decades the college-educated voters skewed heavily towards the Republican party, eventually high educational attainment was a marker of Democratic support.

This formed the political system in the Reagan Era of the 1980s and beyond.

In 1980 conservative Republican Ronald Reagan defeated an incumbent democratic president (Jimmy Carter) on a theme of smaller government, sunny optimism that free trade and tax cuts would stimulate economic growth which would then "trickle down" to the middle and lower classes (who might not benefit initially from these policies). The Republican party was now said to rest on "three legs" of Christian right/Social conservatism (particularly the anti-abortion movement), fiscal conservatism/small government (particularly supporters of tax cuts), and strong anti-communist military policy (with increased willingness to intervene abroad).

- Newt Gingrich, Karl Rove

In 1995, after 40 years of uninterrupted dominance by the Democratic Party, Republican gained 54 seats to take control of the House of Representatives, (it also took control of the Senate). This was in part because the South turned Republican, and in part because of the leadership of Newt Gingrich and his "Republican Revolution". Gingrich introduced a change in norms that continued with Donald Trump of eliminating the idea that Democrats were opponents in elections but later colleagues to negotiate and compromise with in the interest of good legislation. Instead they were the enemy to be attacked and defeated, to be denounced as "traitors ..liars, ... cheaters".

Karl Rove, the political strategist of George W. Bush (president 2001 to 2009), also eliminated norms of behavior between the parties (such as not questioning the patriotism of the other side, seeking bipartisan cooperation), which were often very effective though they increased polarization. Rove emphasized elections are won by energizing the party base of support, not reaching out to the persuadable or swing voter in the middle; attacking opponents strong points (for example implying decorated veterans were treasonous, accusing Max Cleland who had lost three limbs in combat of being sympathetic to terrorism, Silver and Bronze Star wearing John Kerry of being a traitor to his country). Conspiracy theories also began to become mainstream during this time (accusing Hillary Clinton of ordering the military to not protect Americans at the U.S. compound in Benghazi, that the Clintons ordered the murder of Bill's childhood friend Vince Foster), which remained energizing for the base no matter how many times they were investigated and debunked.

Seventh Party System (2016?–present)

While not everyone agrees that a seventh party system has begun, many have noted unique features of a political era starting with the campaign of Donald Trump for president.

- Donald Trump

In the Republican Party, "Reagan Revolution" rhetoric and policy, began to be replaced by new themes. Not only had conservative (white) blue collar workers migrated to the Republican Party, but a business class that had been part of the Republican Party since the post-Civil War Gilded Age began moving left. "Today’s G.O.P. is most clearly now the party of local capitalism—the small-business gentry, the family firms", while "much of corporate America has swung culturally into liberalism’s camp. ... the party’s base regards corporate institutions—especially in Silicon Valley, but extending to more traditional capitalist powers—as cultural enemies", according to Ross Douthat. There was more emphasis on cultural/attitudinal conservatism (opposition not just to abortion but to gay marriage, transgender rights); support for free trade and liberal immigration was replaced by opposition to economic globalization and immigration from non-European countries. Unprecedented distrust of institutions (refused to accept the results of 2020 presidential election), unprecedented loyalty for Donald Trump even after he had lost his second run for election in 2020. President Trump was impeached by the U.S. House of Representatives twice. Both times when the charges were brought to the U.S. Senate, the U.S. Senate acquitted President Trump.

Minor parties and independents

Although American politics have been dominated by the two-party system, "third" political parties have appeared from time to time in American history but seldom lasted more than a decade. They have sometimes been the vehicle of an individual (Theodore Roosevelt's "Bull Moose" party, Ross Perot's Reform Party); had considerable strength in particular regions (Socialist Party, the Farmer-Labor Party (of Minnesota), Wisconsin Progressive Party, Conservative Party of New York State, and the Populist Party); or continued to run candidates for office to publicize ideas despite seldom winning even local elections (Libertarian Party, Natural Law Party, Peace and Freedom Party).

The oldest third party was the Anti-Masonic Party, which was formed in upstate New York in 1828. The party's creators feared the Freemasons, believing they were a powerful secret society that was attempting to rule the country in defiance of republican principles.

Some other significant but unsuccessful parties that ran a candidate for president include: The Know Nothing or American Party (1844-1860), People's Party (Populist) candidate James B. Weaver (1892), Theodore Roosevelt's Progressive or "Bull Moose party" (1912), Robert M. La Follette's Progressive Party (1924) Strom Thurmond's Dixiecrat States Rights Party (1948), Henry A. Wallace's Progressive Party (1948), George Wallace's American Independent Party (1968), Ross Perot's (running as an independent) (1992).

Organization of American political parties

American political parties are more loosely organized than those in other countries, and the Democratic and Republican party have no formal organization at the national level that controls membership. Thus, for example, in many states the process to determine who will be the party's candidate for office is a public election (a political primary) open to all who have signed up as affiliated with that party when they register to vote; and are not limited to those who donate money and are active in the party.

Party identification becomes somewhat formalized when a person runs for partisan office. In most states, this means declaring oneself a candidate for the nomination of a particular party and intent to enter that party's primary election for an office. A party committee may choose to endorse one or another of those who is seeking the nomination, but in the end the choice is up to those who choose to vote in the primary, and it is often difficult to tell who is going to do the voting.

The result is that American political parties have weak central organizations and little central ideology, except by consensus. Unlike in many countries, the party leadership cannot prevent a person who disagrees with basic principles and positions of the party, or actively works against the party's aims, from claiming party membership, so long as the voters who choose to vote in the primary elections elect that person. Once in office, elected officials who fail to "toe the party line" because of constituent opposition to it, and "cross the aisle" to vote with the opposition, have (relatively) little to fear from their party. An elected official may change parties simply by declaring such intent.

At the federal level, each of the two major parties has a national committee (See, Democratic National Committee, Republican National Committee) that acts as the hub for much fund-raising and campaign activities, particularly in presidential campaigns. The exact composition of these committees is different for each party, but they are made up primarily of representatives from state parties and affiliated organizations, and others important to the party. However, the national committees do not have the power to direct the activities of members of the party.

Both parties also have separate campaign committees which work to elect candidates at a specific level. The most significant of these are the "Hill committees", which work to elect candidates to each house of Congress.

State parties exist in all fifty states, though their structures differ according to state law, as well as party rules at both the national and the state level.

Despite these weak organizations, elections are still usually portrayed as national races between the political parties. In what is known as "presidential coattails", candidates in presidential elections become the de facto leader of their respective party, and thus usually bring out supporters who in turn then vote for his party's candidates for other offices. On the other hand, federal midterm elections (where only Congress and not the president is up for election) are usually regarded as a referendum on the sitting president's performance, with voters either voting in or out the president's party's candidates, which in turn helps the next session of Congress to either pass or block the president's agenda, respectively.

The two-party system in the U.S.

As noted above, the modern political party system in the United States is a two-party system, with the parties being the Democratic Party and the Republican Party. Explanations for why America has a two party system include:

- The traditional American electoral format of single-member districts where the candidate with the most votes wins ("first-past-the-post" system), which according to Duverger's law favors the two-party system. This is in contrast to multi-seat electoral districts and proportional representation found in some other democracies.

- the 19th century innovation of printing "party tickets" to pass out to prospective voters to cast in ballot boxes (originally, voters went to the polls and publicly stated which candidate they supported), "consolidated the power of the major parties".

- Printed party "tickets" (ballots) were eventually replaced by uniform ballots provided by the state, when states began to adopt the Australian Secret Ballot Method. This gave state legislatures—dominated by Democrats and Republicans—the opportunity to handicap new rising parties with ballot access laws requiring a large number of petition signatures from citizens and giving the petitioners a short length of time to gather the signatures.

Some (Nelson W. Polsby writing before 1997) have argued that the lack of central control of the parties in America means they have become as much "labels" to mobilize voters as political organizations, and that "variations (sometimes subtle, sometimes blatant) in the 50 political cultures of the states yield considerable differences", suggesting that "the American two-party system" actually masks "something more like a hundred-party system."

Others (Lee Drutman, Daniel J. Hopkins writing before 2018) argue that in the 21st century, along with becoming overly partisan, America politics has become overly focused on national issues and "nationalized".

Major parties

| American voter registration statistics as of October 2020 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Registered voters | Percentage | |

|

|

Democratic | 48,517,845 | 39.58 |

|

|

Republican | 36,132,743 | 29.48 |

|

|

No party preference | 34,798,906 | 28.39 |

|

|

Other | 3,127,800 | 2.55 |

| Totals | 122,577,294 | 100.00 | |

Democratic Party

The Democratic Party is one of two major political parties in the U.S. Founded as the Democratic Party in 1828 by Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren, it is the oldest extant voter-based political party in the world.

Until the mid-20th century, the Democratic Party was the dominant party among white southerners, and as such, was then the party most associated with the defense of slavery. However, following the Great Society under Lyndon B. Johnson, the Democratic Party became the more progressive party on issues of civil rights, they would slowly lose dominance in southern states until 1996.

The Democratic Party since 1912 has positioned itself as the liberal party on domestic issues. The economic philosophy of Franklin D. Roosevelt, which has strongly influenced modern American liberalism, has shaped much of the party's agenda since 1932. Roosevelt's New Deal coalition controlled the White House until 1968, with the exception of the two terms of President Eisenhower from 1953 to 1961. Since the mid-20th century, Democrats have generally been in the center-left and currently support social justice, social liberalism, a mixed economy, and the welfare state, although Bill Clinton and other New Democrats have pushed for free trade and neoliberalism, which is seen to have shifted the party rightwards. Democrats are currently strongest in the Northeast and West Coast and in major American urban centers. African-Americans and Latinos tend to be disproportionately Democratic, as do trade unions.

In 2004, it was the largest political party, with 72 million registered voters (42.6% of 169 million registered) claiming affiliation. Although his party lost the election for president in 2004, Barack Obama would later go on to become president in 2009 and continue to be the president until January 2017. Obama was the 15th Democrat to hold the office, and from the 2006 midterm elections until the 2014 midterm elections, the Democratic Party was also the majority party in the United States Senate.

A 2011 USA Today review of state voter rolls indicates that the number of registered Democrats declined in 25 of 28 states (some states do not register voters by party). During this time, Republican registration also declined, as independent or no preference voting was on the rise. However, in 2011 Democrats numbers shrank 800,000, and from 2008 they were down by 1.7 million, or 3.9%. In 2018, the Democratic party was the largest in the United States with roughly 60 million registered members.

Republican Party

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States of America. Since the 1880s it has been nicknamed (by the media) the "Grand Old Party" or GOP, although it is younger than the Democratic Party. Founded in 1854 by Northern anti-slavery activists and modernizers, the Republican Party rose to prominence in 1860 with the election of Abraham Lincoln, who used the party machinery to support victory in the American Civil War.

The GOP dominated national politics during the Third Party System, from 1854 to 1896, and the Fourth Party System from 1896 to 1932. Since its founding, the Republican Party has been the more market-oriented of the two American political parties, often favoring policies that aid American business interests. As a party whose power was once based on the voting power of Union Army veterans, this party has traditionally supported more robust national defense measures and improved veterans' benefits. Today, the Republican Party supports an American conservative platform, with further foundations in economic liberalism, fiscal conservatism, and social conservatism. The Republican Party tends to be strongest in the Southern United States, outside large metropolitan areas, or in less-centralized, lower-density parts of them.

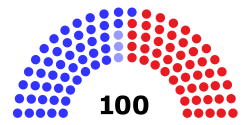

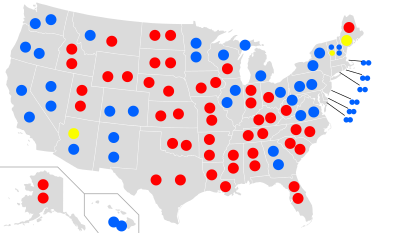

Since the 2010 midterm elections, the Republicans held a majority in the United States House of Representatives until the 2018 midterms where they lost it to the Democratic Party. Additionally, from the 2014 elections to the 2020 elections, the Republican Party controlled the Senate. In 2018, the Republican party had roughly 55 million registered members, making it the second largest party in the United States. In the aftermath of the 2020 United States elections, the GOP lost their senate majority, and Chuck Schumer was appointed Senate Majority Leader in a power-sharing agreement with the Republican Party.

Minor parties

The United States also has an array of minor parties, the largest of which (on the basis of voter registrations as of October 2020), are the Libertarian, Green, and Constitution parties. (There are many other political parties that receive only minimal support and only appear on the ballot in one or a few states.)

Libertarian Party

The Libertarian Party was founded on December 11, 1972. As of March 2021, it is the largest third party in the United States, claiming nearly 700,000 registered voters across 28 states and the District of Columbia. As of August 2022, it has 309 local elected officials, and one state representative: Marshall Burt of Wyoming. Former Representative Justin Amash, a former Republican and later independent from Michigan, switched to the Libertarian Party in May 2020, to become the first Libertarian Party member of Congress. Amash declined to run for reelection in 2020 and left office on January 3, 2021.

The 2012 Libertarian Party nominee for United States President was former New Mexico governor, Gary Johnson. He achieved ballot access in every state except for Michigan (only as a write-in candidate) and Oklahoma. He received over one million votes in the election. In 2016, Johnson ran again, receiving over four million votes, or 3.3% of the popular vote.

The Libertarian Party's core mission is to reduce the size, influence, and expenditures in all levels of government. To this effect, the party supports minimally regulated markets, a less powerful federal government, strong civil liberties, drug liberalization, open immigration, non-interventionism and neutrality in diplomatic relations, free trade and free movement to all foreign countries, and a more representative republic. As of October 2020 , it is the third largest political party in the United States based on voter registration.

Green Party

The Green Party has been active as a third party since the 1980s. The party first gained widespread public attention during Ralph Nader's second presidential run in 2000. Currently, the primary national Green Party organization in the U.S. is the Green Party of the United States, which has eclipsed the earlier Greens/Green Party USA.

The Green Party in the United States has won elected office mostly at the local level; most winners of public office in the United States who are considered Greens have won nonpartisan-ballot elections (that is, elections in which the candidates' party affiliations were not printed on the ballot). In 2005, the Party had 305,000 registered members in the District of Columbia and 20 states that allow party registration. During the 2006 elections the party had ballot access in 31 states. In 2017, Ralph Chapman, a Representative in the Maine House of Representative switched his association from Unaffiliated to the Green Independent Party.

The United States Green Party generally holds a left-wing ideology on most important issues. Greens emphasize environmentalism, non-hierarchical participatory democracy, social justice, respect for diversity, peace, and nonviolence. As of October 2020, it is the fourth largest political party in the United States based on voter registration.

Constitution Party

The Constitution Party is a national conservative political party in the United States. It was founded as the U.S. Taxpayers Party in 1992 by Howard Phillips. The party's official name was changed to the "Constitution Party" in 1999; however, some state affiliate parties are known under different names. As of October 2020, it is the fifth largest political party in the United States based on voter registration.

Alliance Party

The Alliance Party is a centrist American political party that was formed in 2018 and registered in 2019. The Alliance Party gained affiliation status with multiple other parties, including the American Party of South Carolina, the Independence Party of Minnesota, and the Independent Party of Connecticut. During the 2020 Presidential Elections Alliance Party Presidential Candidate Roque De La Fuente placed fifth in terms of the popular vote. Following the presidential election, the American Delta Party and the Independence Party of New York joined the Alliance Party. The Independence Party of New York disaffiliated in 2021.

Alternative interpretations

Multiple individuals from various stances have proposed an end to the two-party system, arguing mostly that the Democratic and Republican parties don't accurately represent much of the national electorate, or that multiple political parties already exist within the Democratic and Republican parties which encompass a variety of views.

Four Party interpretations

NBC News' Dante Chinni and Washington Post columnist Perry Bacon, Jr. have both suggested that the United States' political system is that of four parties grouped into a two-party system. Due mostly to competing influence from larger personalities within such parties, Chinni and Bacon have grouped the American populace into four primary political parties:

- Trump Republicans, which includes Trump's followers, Ron DeSantis, the Christian right, and Fox News. In light of President Biden's 2020 win, this group has been seen as the least willing to compromise with Biden and the most likely to believe the 2020 election was stolen.

- Party Republicans, or "the Old Guard", consisting of Trump-skeptical and anti-Trump Republicans such as Mitch McConnell, Mitt Romney, and Larry Hogan. This group's intention is much more so to preserve the traditional Republican agenda of lifting regulations and tax cuts.

- Center-left Democrats, composed of some Never-Trumpers, Biden, Pelosi, Eric Adams, and the Third Way movement. This group wishes to pass Biden's agenda the strongest of any group and prefers to pass a moderate Democratic agenda.

- Left-left Democrats, the most likely to embrace progressive politics and more willing to hinder Biden's agenda in favor of more leftward policies. This faction's leaders include Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Bernie Sanders, Michelle Wu, and the Progressive Caucus.

Six Party interpretations

The idea the United States primarily falls into six political parties is pushed by former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich, American political theorists Lee Drutman, and political theorist Carl Davidson. Drutman argues that government without two parties would enable and support "the shifting alliances and bargaining that are essential in democracy" which have largely been lost in a two party system due to political gridlock. Reich further predicts that these parties likely emerge as the two parties "explode".

All three theorists have consensus that these four parties will exist within a six-party system:

- One party would be founded on hard-line supporters of Donald Trump, his namesake grouping of ideas, economic nationalism, and right-wing populism. Their primary funders would be Trump-affiliated Arabian oil firms and Russian oligarchs.

- Establishment Republicans would be composed of socially moderate but pro-business (Rockefeller-style) Republicans, corporations and existing GOP megadonors, who aspire to cut their taxes. Both Reich and Davidson attribute this to be the party of big business, and cite ExxonMobil and other Big Oil companies in particular as an example for this party.

- Christian nationalists and Christian conservatives would form their own voting bloc. Davidson notes that the Koch family and Betsy DeVos are major backers of this segment of the populace.

- American progressives would form a bloc which would push an agenda advocating for social justice, full LGBTQ rights, ending crony capitalism, and fighting climate change. Those who identify as socialist within the American political system would be core members, and its funding base is primarily unions and grassroots donations.

The three interpretations, however, differ on the inclusion of these parties:

- Reich views libertarians, and the Tea Party and Freedom Caucus movements, as anti-establishment Republicans who aspire to shrink government and also end crony capitalism. Drutman views these groups as split between the party of Trumpism and Christian conservatives, and Davidson views the Tea Party and Freedom Caucus as the foundations for his Christian nationalists party,

- Drutman outlines another party which aims to represent working-class democrats who are not as socially liberal as American progressives though is just as economically liberal.

- Davidson splits moderate Democrats into two parties; the first is named for the Blue Dog Coalition and aligns more so with United Steelworkers as well as the pharmaceutical industry, while the other represents mainstream Democrats and is symbolized by Barack Obama, Nancy Pelosi, Hollywood personalities, and large banks like JPMorgan Chase. Drutman and Reich, however, categorize both as "Establishment Democrats" which prefer tax cuts but also back equal rights.