| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

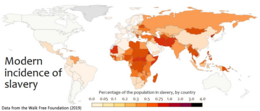

Contemporary slavery, also sometimes known as modern slavery or neo-slavery, refers to institutional slavery that continues to occur in present-day society. Estimates of the number of enslaved people today range from around 38 million to 46 million, depending on the method used to form the estimate and the definition of slavery being used. The estimated number of enslaved people is debated, as there is no universally agreed definition of modern slavery; those in slavery are often difficult to identify, and adequate statistics are often not available. The International Labour Organization estimates that, by their definitions, over 40 million people are in some form of slavery today. 24.9 million people are in forced labor, of whom 16 million people are exploited in the private sector such as domestic work, construction or agriculture; 4.8 million persons in forced sexual exploitation, and 4 million persons in forced labour imposed by state authorities. An additional 15.4 million people are in forced marriages.

Definition

The Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, an agency of the United States Department of State, says that "'modern slavery', 'trafficking in persons', and 'human trafficking' have been used as umbrella terms for the act of recruiting, harbouring, transporting, providing or obtaining a person for compelled labour or commercial sex acts through the use of force, fraud, or coercion". Besides these, a number of different terms are used in the US federal Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000 and the United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children, including "involuntary servitude", "slavery" or "practices similar to slavery", "debt bondage", and "forced labor".

According to American professor Kevin Bales, co-founder and former president of the non-governmental organization and advocacy group Free the Slaves, modern slavery occurs "when a person is under the control of another person who applies violence and force to maintain that control, and the goal of that control is exploitation". The impact of slavery is expanded when targeted at vulnerable groups such as children. According to this definition, research from the Walk Free Foundation based on its Global Slavery Index 2018 estimated that there were about 40.3 million slaves around the world. In another estimate that suggests the number is around 45.8 million, it is estimated that around 10 million of these contemporary slaves are children. Bales warned that, because slavery is officially abolished everywhere, the practice is illegal, and thus more hidden from the public and authorities. This makes it impossible to obtain exact figures from primary sources. The best that can be done is to estimate based on secondary sources, such as UN investigations, newspaper articles, government reports, and figures from NGOs. Modern slavery persists for many of the same reasons older variations did: it is an economically beneficial practice despite the ethical concerns. The problem has been able to escalate in recent years due to the disposability of slaves and the fact that the cost of slaves has dropped significantly.

Causes

Since slavery has been officially abolished, enslavement no longer revolves around legal ownership, but around illegal control. Two fundamental changes are the move away from the forward purchase of slave labour, and the existence of slaves as an employment category. While the statistics suggest that the 'market' for exploitative labour is booming, the notion that humans are purposefully sold and bought from an existing pool is outdated. While such basic transactions do still occur, in contemporary cases people become trapped in slavery-like conditions in various ways.

Modern slavery is often seen as a by-product of poverty. In countries that lack education and the rule of law, poor societal structure can create an environment that fosters the acceptance and propagation of slavery. Slavery is most prevalent in impoverished countries and those with vulnerable minority communities, though it also exists in developed countries. Tens of thousands toil in slave-like conditions in industries such as mining, farming, and factories, producing goods for domestic consumption or export to more prosperous nations.

In the older form of slavery, slave-owners spent more on getting slaves. It was more difficult for them to be disposed of. The cost of keeping them healthy was considered a better investment than getting another slave to replace them. In modern slavery people are easier to get at a lower price so replacing them when exploiters run into problems becomes easier. Slaves are then used in areas where they could easily be hidden while also creating a profit for the exploiter. Slaves are more attractive for unpleasant work, and less for pleasant work.

Modern slavery can be quite profitable, and corrupt governments tacitly allow it, despite its being outlawed by international treaties such as Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery and local laws. Total annual revenues of traffickers were estimated in 2014 to over $150 billion, though profits are substantially lower. American slaves in 1809 were sold for around the equivalent of US$40,000 in today's money. Today, a slave can be bought for $90–$100.

Bales explains, “This is an economic crime ... People do not enslave people to be mean to them; they do it to make a profit.”

Types

Slavery by descent and chattel slavery

Slavery by descent, also called chattel slavery, is the form most often associated with the word "slavery". In chattel slavery, the enslaved person is considered the personal property (chattel) of someone else, and can usually be bought and sold. It stems historically either from conquest, where a conquered person is enslaved, as in the Roman Empire or Ottoman Empire, or from slave trading, as in the Atlantic slave trade.

Since the 2014 Civil War in Libya, and the subsequent breakdown of law and order, there have been reports of enslaved migrants being sold in public, including open slave markets in the country.

Mauritania has a long history with slavery. Chattel slavery was formally made illegal in the country but the laws against it have gone largely unenforced. It is estimated that around 90,000 people (over 2% of Mauritania's population) are slaves.

Debt bondage can also be passed down to descendants, like chattel slavery.

Those trapped in the system of sexual slavery in the modern world are often effectively chattel, especially when they are forced into prostitution.

Government-forced labor

Government-forced labor, also known as state-sponsored labor, is defined by the International Labour Organization as events "which persons are coerced to work through the use of violence or intimidation, or by more subtle means such as accumulated debt, retention of identity papers or threats of denunciation to immigration authorities." When the threats come from the government the threats can be much different. Many governments that participate in forced labor shut down their connections with the surrounding countries to prevent citizens from leaving.

In North Korea, the government forces many people to work for the state, both inside and outside North Korea itself, sometimes for many years. The 2018 Global Slavery Index estimated that 2.8 million people were slaves in the country. The value of all the labor done by North Koreans for the government is estimated at US$975 million, with dulgyeokdae (youth workers) forced to do dangerous construction work, and inminban (women and girl workers) forced to make clothing in sweatshops. The workers are often unpaid. Additionally, North Korea's army of 1.2 million conscripted soldiers is often made to work on construction projects unrelated to defense, including building private villas for the elite. The government has had as many as 100,000 workers abroad.

In Eritrea, an estimated 300,000 to 400,000 people are in an indefinite military service program which amounts to mass slavery, according to UN investigators. Their report also found sexual slavery and other forced labor.

Government-forced labor comes in different forms, as governments have also been known to participate in forced-labor practices that do not include military service. In Uzbekistan, for example, the government coerces students and state workers to harvest cotton, of which the country is a main exporter, every year, forcing them to abandon their other responsibilities in the process. In this example the use of students, including those in primary, secondary, and higher education, means that child labor is also prominent. Uzbekistan's government has worked to reduce the forced labor in recent years, and in March 2022 a major boycott of Uzbek cotton was lifted, upon reports that coerced labor had been almost eliminated.

Prison labor

In 1865, the United States ratified the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution, which banned slavery and involuntary servitude "except as punishment for a crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted", providing a legal basis for slavery, now referred to as penal labor, to continue in the country. Historically, this led to the system of convict leasing which still primarily affects African-Americans. The Prison Policy Initiative, an American criminal justice think tank, cites the 2020 US prison population at being 2.3 million individuals, and nearly all able-bodied inmates work in some fashion. In Texas, Georgia, Alabama and Arkansas, prisoners are not paid at all for their work. In other states, prisoners are paid between $0.12 and $1.15 per hour. Federal Prison Industries paid inmates an average of $0.90 per hour in 2017. Inmates that refuse to work may be indefinitely remanded into solitary confinement, or have family visitation revoked. From 2010 to 2015 and again in 2016 and in 2018, some prisoners in the US refused to work, protesting for better pay, better conditions, and for the end of forced labor. Strike leaders were punished with indefinite solitary confinement. Forced prison labor occurs in both public/government-run prisons and private prisons. CoreCivic and GEO Group constitute half of the market share of private prisons, and they made a combined revenue of $3.5 billion in 2015. The value of all the labor done by inmates in the United States is estimated to be in the billions. In California, 2,500 incarcerated workers are fighting wildfires for only $1 per hour through the CDCR's Conservation Camp Program, which saves the state as much as $100 million a year.

In China's system of labor prisons (formerly called laogai), millions of prisoners have been subject to forced, unpaid labor. The laogai system is estimated to currently house between 500,000 and 2 million prisoners, and to have caused tens of millions of deaths. In parallel with laogai, China operated the smaller re-education through labor system of prisons up until 2013. In addition to both of these, China is also operating forced labor camps in Xinjiang, imprisoning hundreds of thousands (possibly as many as a million) of Muslims, Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities and political dissidents.

In North Korea, tens of thousands of prisoners may be held in forced labor camps. Prisoners suffer harsh conditions and have been forced to dig their own graves and to throw rocks at the dead body of another prisoner. At Yodok Concentration Camp, children and political prisoners were subject to forced labor. Yodok closed in 2014 and its prisoners were transferred to other prisons.

In the UK there are three key types of prison labour. Firstly, prisoners can be made to maintain the jail—for example cleaning, maintenance, or working in the kitchens. Second, prisoners have the option to do mundane/repetitive work for external companies; this includes tasks such as bagging nails and packing boxes. Finally, prisoners can work in specialist workshops run by third parties, in which the prisoners can do tasks such as building window-frames, graphic design and other tasks requiring some form of machinery. Reports suggest prisoners in the UK can earn as little as £10 for a 40-hour week's worth of work.

In Australia, prison labour occurs in at least New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland and the Northern Territory. Some prisoners work for private companies. In NSW some are paid as little as $0.82 per hour, while in the NT some are paid as much as $16 per hour (compared to $35 per hour for a regular union employee in the same job).

Bonded labor

Bonded labor, also known as debt bondage and peonage, occurs when people give themselves into slavery as a security against a loan or when they inherit a debt from a relative. The cycle begins when people take extreme loans under the condition that they work off the debt. The "loan" is designed so that it can never be paid off, and is often passed down for generations. People become trapped in this system working ostensibly towards repayment though they are often forced to work far past the original amount they owe. They work under the force of threats and abuse. Sometimes the debts last a few years, and sometimes the debts are even passed onto future generations.

Bonded labor is used across a variety of industries in order to produce products for consumption around the world. It is most common in India, Pakistan and Nepal.

In India, the majority of bonded laborers are Dalits (Untouchables) and Adivasis (indigenous tribespeople). Puspal, a former brick kiln worker in Punjab, India, stated in an interview to antislavery.org; "We do not stop even if we are ill – what if our debt is increasing? So we don't dare to stop." In India, when compared to the price of land, paid labor or oxen, the price of slaves is currently 95% less than it was in the past.

Forced migrant labor

People may be enticed to migrate with the promise of work, only to have their documents seized and be forced to work under the threat of violence to them or their families. Undocumented immigrants may also be taken advantage of, as without legal residency they often have no legal recourse. Along with sex slavery, this is the form of slavery most often encountered in wealthy countries such as the United States, in Western Europe, and in the Middle East.

In the United Arab Emirates, some foreign workers are exploited and more or less enslaved. The majority of the UAE resident population are foreign migrant workers rather than local Emirati citizens, with there being over 1.7 million migrant workers, making up 90% of the constructive workforce. The country has a kafala system which is associated with outdated laws and procedures, which ties migrant workers to local Emirati sponsors with very little government oversight. This has often led to forced labor and human trafficking. In 2017, the UAE is pushing towards a better labor system as it has recently passed laws to protect the rights of domestic workers.

Allegations of forced migrant labor have been highlighted within the preparations of stadiums for the Qatar FIFA 2022 World Cup. There have been over 6,500 recorded migrant deaths during the construction of the stadiums. Amnesty International researched into the construction of the stadiums and found 3,200 migrant workers work on the stadiums everyday, in which at least 224 of them have reported abusive and exploitative behaviour. Workers reported issues of expensive recruitment fees, poor living conditions, false salaries, delayed payments of salary, being unable to leave the stadium or camp, being unable to leave the country or change jobs, being threatened, and most importantly forced labour.

In October 2019 Qatar abolished Kafala system and introduced basic minimum wage and wage protection system for migrant workers. Under these reforms workers can change jobs without employer's permission and are now paid basic minimum wage regardless of their nationality. The basic minimum wage is set to 1,000 QAR and allowances for food and accommodation must be provided by employers which is 300 QAR and 500 QAR respectively. Moreover, Qatar introduced a wage protection system to ensure the employers are complying with the reforms. The wage protection system monitors the workers in the private sector. This new system has reduced wage abuses and disputes among migrant labours.

Additionally in the UK two individuals in Kent were found guilty of trafficking six Lithuanian men. They were forced to work back to back 8 hour shifts working as chicken catchers. Further investigations into this highlighted the farms these individuals were working at were supplying eggs to large supermarket chains such as Tesco's, Asda and M&S. Vietnamese teenagers are trafficked to the United Kingdom and forced to work in illegal cannabis farms. When police raid the cannabis farms, trafficked victims are typically sent to prison.

In the United States, various industries have been known to take advantage of forced migrant labor. During the 2010 New York State Fair, 19 migrants who were in the country legally from Mexico to work in a food truck were essentially enslaved by their employer. The men were paid around ten percent of what they were promised, worked far longer days than they were contracted to, and would be deported if they had quit their job as this would be a violation of their visas. A 2021 multi-agency federal investigation dubbed "Operation Blooming Onion" revealed that a years long human trafficking ring forced migrant workers from Mexico and Central America into "modern day slavery" on various agricultural sites in southern Georgia. The indictment alleges that in the fields the migrant workers were forced at gunpoint to dig for onions with their bare hands for 20 cents per bucket. They were held in work camps surrounded by electrified fences and subjected to squalid and crammed living conditions, with no access to safe food or water.

Reports of migrant abuse and neglect surfaced in Kenya in early September 2022, when pictures of a frail looking young Kenyan worker from Saudi, Diana Chepkemoi went viral. Following growing pressure from public, the government repatriated Chepkemoi along with a few other domestic workers facing a similar fate in the Kingdom. Among those rescued was Joy Simiyu, who went to Saudi to work as a domestic help, but within months returned to Kenya with a harrowing, but known tale of abuse by her employer. According to reports, migrant housekeepers complained of being subjected to physical, mental as well as sexual abuse while working in the Gulf state.

Sex slavery

Along with migrant slavery, forced prostitution is the form of slavery most often encountered in wealthy regions such as the United States, in Western Europe, and in the Middle East. It is the primary form of slavery in Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia, particularly in Moldova and Laos. Many child sex slaves are trafficked from these areas to the West and the Middle East. An estimated 20% of slaves to date are active in the sex industry. Sexual exploitation can also become a form of debt bondage when enslavers insist that victims work in the sex industry to pay for basic needs and transportation.

In 2005, the Gulf Times reported that boys from Nepal had been lured to India and enslaved for sex. Many of these boys had also been subject to male genital mutilation (castration).

Many of those who become victims of sex slavery initially do so willingly under the guise that they will be performing traditional sex work, only to become trapped for extended periods of time, such as those involved in Nigeria's human trafficking circuit.

Forced marriage and child marriage

Mainly driven by the culture in certain regions, early or forced marriage is a form of slavery that affects millions of women and girls all over the world. When families cannot support their children, the daughters are often married off to the males of wealthier, more powerful families. These men are often significantly older than the girls. The females are forced into lives whose main purpose is to serve their husbands. This often fosters an environment for physical, verbal and sexual abuse.

Forced marriages also happen in developed nations. In the United Kingdom there were 3,546 reports to the police of forced marriage over three years from 2014 to 2016.

In the United States over 200,000 minors were legally married from 2002 to 2017, with the youngest being only 10 years old. Most were married to adults. Currently 48 US states, as well as D.C. and Puerto Rico, allow marriage of minors as long as there is judicial consent, parental consent or if the minor is pregnant. In 2017–2018, several states began passing laws to either restrict child marriage or ban it altogether.

Bride-buying is the act of purchasing a bride as property, in a similar manner to chattel slavery. It can also be related to human trafficking.

Child labor

Children comprise about 26% of the slaves today. Although children can legally engage in certain forms of work, children can also be found in slavery or slavery-like situations; although child labor isn't considered slavery, it inevitably hinders their education. Forced begging is a common way that children are forced to participate in labor without their consent. Most are domestic workers or work in cocoa, cotton or fishing industries. Many are trafficked and sexually exploited. Forced child labor is the dominant form of slavery in Haiti.

In war-torn countries, children have been kidnapped and sold to political parties to use as child soldiers. Child soldiers are children who may be trafficked from their homes and forced or coerced by armed forces. The armed forces could be government armed forces, paramilitary organizations, or rebel groups. While in these groups the children may be forced to work as cooks, guards, servants or spies. It is common for both boys and girls to be sexually abused while in these groups.

Fishing industry

According to Human Rights Watch, Thailand's billion-dollar fish export industry remains plagued with human rights maltreatment in spite of government vows to stamp out servitude in its angling industry. Human Rights Watch conducted interviews with 248 fishermen, it documented the forced labor of trafficked workers in the Thai fishing industry. Trafficking victims are often tricked by brokers' false promises of "good" factory jobs, then forced onto fishing boats where they are trapped, bought and sold like livestock, and held against their will for months or years at a time, forced to work grueling 22-hour days in dangerous conditions. Those who resist or try to run away are beaten, tortured, and often killed. This is commonplace because of the disposability of unfree laborers.

Despite some improvements, the situation has not changed much since a large-scale survey of almost 500 fishers in 2012, that found almost one in five "reported working against their will with the penalty that would prevent them from leaving".

Forced begging

Victims of human trafficking can be made to beg on the streets with the earnings being given back to the traffickers. It has been suggested many children across Europe, Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Middle East are forced to beg on the streets.

Occupations

In addition to sex slavery, modern slaves are often forced to work in certain occupations. Common occupations include:

- Small-scale building work, such as laying driveways, and other labor.

- Car washing by hand

- Domestic servitude, sometimes with sexual exploitation.

- Nail salons (cosmetic). Many people are trafficked from Vietnam to the UK for this work.

- Fishing, mainly associated with Thailand's sea food industry.

- Manufacturing – Many prisoners in the US are forced to manufacture products as diverse as mattresses, spectacles, underwear, road signs and body armour.

- Agriculture and forestry – Prisoners in the United States and China are often forced to do farming and forestry work. See prison farm.

- In North Korea, dulgyeokdae (youth workers) are often forced to work in construction and inminban (women workers) are forced to work in clothing sweatshops.

Signs that someone may have been forced into slavery include a lack of identity documents, lack of personal possessions, clothing that is unsuitable or has seen much wear, poor living conditions, a reluctance to make eye contact, unwillingness to talk, and unwillingness to seek help. In the UK, people are encouraged to report suspicions to a modern-slavery telephone helpline.

The European Parliament condemned, 386 — 236 with 59 abstentions, the humanitarian practice of sending Cuban doctors to fight the COVID-19 pandemic around the world as human trafficking and modern slavery.

Trafficking

The United Nations have defined human trafficking as follows:

The recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labor or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs.

According to United States Department of State data, as of 2013, an "estimated 600,000 to 820,000 men, women, and children [are] trafficked across international borders each year, approximately 70 percent are women and girls and up to 50 percent are minors. The data also illustrates that the majority of transnational victims are trafficked into commercial sexual exploitation." However, "the alarming enslavement of people for purposes of labor exploitation, often in their own countries, is a form of human trafficking that can be hard to track from afar". It is estimated that 50,000 people are trafficked every year in the United States.

In recent years, the internet and popular social networking sites have become tools that traffickers use to find vulnerable people who they can then exploit. A 2017 Reuters report discusses how a woman is suing Facebook for negligence as she speculated that executives were aware of a situation that occurred back in 2012 where she was sexually abused and trafficked by someone posing as her "friend". Social media and smartphone apps are also used to sell the slaves.

In 2016, a Washington Post article exposed that the Obama administration placed migrant children with human traffickers. They failed to do proper background checks of adults who claimed the children, allowed sponsors to take custody of multiple unrelated children, and regularly placed children in homes without visiting the locations. Several Guatemalan teens were found being held captive by traffickers and forced to work at a local egg farm in Ohio.

Organizational efforts against slavery

Government actions

In the last two decades, as slavery has become more widely recognized as a formidable global epidemic, multiple governmental organizations have begun taking action to address the problem. The US State Department's annual Trafficking In Persons Report assigns grades to every nation in a tier-system based "not on the size of the country’s problem but on the extent of governments’ efforts to meet the TVPA's minimum standards for the elimination of human trafficking".

The governments credited with the strongest response to modern slavery are the Netherlands, the United States, the United Kingdom, Sweden, Australia, Portugal, Croatia, Spain, Belgium, Germany and Norway.

In the United Kingdom, the British government passed the Modern Slavery Act 2015, supported by major reforms in the legal system instituted through the Criminal Finances Act 2017, effective from September 30, 2017. Under the latter act, there is transparency in regards to interbank information sharing with law enforcement agencies to help to crack down on money laundering agencies related to contemporary slavery. The Act also aims at reducing the incidence of tax evasion attributed to the modern slave trade conducted under the domain of the law. Despite this, the government has been refusing asylum and deporting children trafficked to the UK as slaves. Several British charities have claimed this puts the deportees at risk of being subject to control by slavery gangs a second time, and deters child victims from coming forward with information.

The British government has taken specific steps to ensure that modern slavery risks are identified and managed in government supply chains. The government also initiated a nationwide campaign against modern slavery: the "Modern slavery is closer than you think" campaign.

In contrast, the governments accused of taking the least action against it are North Korea, Eritrea, Equatorial Guinea, Hong Kong, Central African Republic, Papua New Guinea, Guinea, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and South Sudan.

The highest court in UK stripped off diplomats with a history of domestic worker abuse from claiming diplomatic immunity, saving them from compensatory claims. The July 2022 ruling concerned the case of a London-based Saudi diplomat, Khalid Basfar, who allegedly treated a Filipino staff member hired by him, to slavery; forcing her to wear a bell throughout the day to be available at for his “family’s beck and call”. The employee, Josephine Wong, was first hired by the Basfar household in November 2015 in Saudi Arabia and brought to the UK to work for him in August 2016. According to court's hearing, Wong was confined to the house except to take the rubbish out. She was allegedly subjected to incessant shouting, offensive names and given leftover food only. The court was requested to judge the issue and determine whether Basfar's treatment of Wong was protected by diplomatic immunity or not, if the case did amount to modern slavery. The concluded that Ms Wong's was a case of modern slavery.

Private initiatives

In September 2013, the three anti-slavery donors, the Legatum Foundation, Humanity United and the Walk Free Foundation founded the Freedom Fund. As of December 2019, the Freedom Fund is reported to have impacted 686,468 lives, liberated 27,397 people from modern slavery and helped 56,181 previously out-of-school children to receive either formal or non-formal education, in Nepal, Ethiopia, India and Thailand. Meanwhile, in October 2014, the Freedom Fund, Polaris and the Walk Free Foundation launched the Global Modern Slavery Directory, which was the first publicly searchable database of over 770 organisations working to end forced labor and human trafficking. BT also teamed up with anti-modern slavery campaigners free the unseen.

Statistics

Modern slavery is a multibillion-dollar industry with just the forced labor aspect generating US$150 billion each year. The Global Slavery Index (2018) estimated that roughly 40.3 million individuals are currently caught in modern slavery, with 71% of those being female, and 1 in 4 being children. As of 2018, the countries with the most slaves were: India (8 million), China (3.86 million), Pakistan (3.19 million), North Korea (2.64 million), Nigeria (1.39 million), Indonesia (1.22 million), Democratic Republic of the Congo (1 million), Russia (794,000) and the Philippines (784,000).

Various jurisdictions now require large commercial organizations to publish a slavery and human trafficking statement in regard to their supply chains each financial year (e.g. California, UK, Australia). The Walk Free Foundation reported in 2018 that 40.3 million people worldwide live in conditions that can be described as slavery. According to the foundation, more than 400,000 of those are in the United States. Andrew Forrest, founder of the organisation, was quoted as saying that "the United States is one of the most advanced countries in the world yet has more than 400,000 modern slaves working under forced labor conditions". In March 2020, released British police records showed that the number of modern slavery offences recorded has increased by more than 50%, from 3,412 cases in 2018 to 5,144 cases in 2019. This coincided with a 68% increase in calls and submissions to the modern slavery helpline over the same time period.

There is an estimate of 10,000 potential victims of modern slavery in the UK.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on modern slavery

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been an impact on the global supply chains including factories in Malaysia providing PPE to the NHS in the UK, and an influx of online clothing shopping which has led factories in third world countries to rapidly expand to deal with the influx of demand. A result of this rapid increase in demand for clothes and PPE has led to some companies using the pandemic as an excuse to exploit vulnerable workers, even forcing them to work through the pandemic putting them at risk of contracting the disease. The pandemic has led to multiple impacts across the globe.

Creation of new risks and abuses for victims

Self-isolation and social isolation is a major aspect of the pandemic, and it may increase the chances for young people to be vulnerable to grooming and abuse due to a lack of contact with friends and family. Ordinarily some Quranic schools in West Africa practice forced begging. Since many of the pupils are now residing within the school premises due to the pandemic, they are subject to further abuse/punishment as a result of them not bringing in as much income.

Wealthy families in Mauritania have exploited the pandemic as well, by firing Haratine domestic workers, or allowing them to work on the condition they are confined within the workplace to avoid travel. This entraps the Haratine people, since if they don't take the work they starve, but if they continue to work they leave their families without resources.

Increased susceptibility to slavery

The use of lockdowns has been implemented to attempt to stop the spread of the virus. This has led to mass firings as a result of global brands cancelling orders resulting in factories shutting down. By March over 1 million workers in Bangladesh have been fired or suspended. Workers in Cambodia, India, Myanmar and Vietnam have experienced similar problems. A lack of government support for citizens has led to an increase of human trafficking as a result of people turning to bonded labour for survival.

Increase in risk for migrant workers

Victims of modern-day slavery are often hesitant to go to the authorities for help due to a fear of being criminalised, detained or deported rather than being treated as victims of a crime. Victims of modern-day slavery often live in cramped conditions in which the Covid virus can spread quickly. This, along with the combination of being fearful to get help from the authorities such as the NHS, leads to victims catching diseases and potentially dying as a result.

Disruption to anti-slavery campaigns

Since most countries have adopted lockdowns, this has led to limited operations of anti-slavery organisations since people were not allowed to meet up during the lockdown. Anti-slavery support services and educational centres have also shut down as a result of the lockdown.

Impact of the pandemic on modern slavery in the UK

The Home Office has stated the number of suspected modern slavery victims in the UK has fallen for the first time in 4 years, as a result of the pandemic. Officials say this is due to the restrictions implemented in the UK and an increase of self-isolation and businesses shutting.

The national referral mechanism has recorded 2,871 referrals of potential modern day slavery victims in the 1st quarter of 2020, which is a 14% fall from the previous 3 months. There has been an increase of child victims "partially driven" by an increase of county lines.

Media

- The documentary film 13th explores the "intersection of race, justice, and mass incarceration in the United States;" It is titled after the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, adopted in 1865, which abolished slavery throughout the United States and ended involuntary servitude, but slavery has been silently perpetuated since that time until the present, through criminalizing behavior and enabling police to arrest poor freedmen and force them to work for the states and the prevalence of massive "carceral states" managed by for profit prison corporations that have created the current carceral capitalism in the United States.

- The documentary film A Woman Captured follows the life of a 52-year-old woman in Hungary who is kept as a modern-day slave.

- There have been a number of documentaries which highlight worker abuse and other human rights issues in the Arab Gulf countries for example Qatar. There are also calls to boycott the 2022 FIFA World cup in Qatar.