| Part of a series on |

| Scandinavia |

|---|

|

The Nordic model comprises the economic and social policies as well as typical cultural practices common to the Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden). This includes a comprehensive welfare state and multi-level collective bargaining based on the economic foundations of social corporatism, and a commitment to private ownership within a market-based mixed economy — with Norway being a partial exception due to a large number of state-owned enterprises and state ownership in publicly listed firms.

Although there are significant differences among the Nordic countries, they all have some common traits. The three Scandinavian countries are constitutional monarchies, while Finland and Iceland have been republics since the 20th century. All the Nordic countries are however described as being highly democratic and all have a unicameral form of governance and use proportional representation in their electoral systems. They all support a universalist welfare state aimed specifically at enhancing individual autonomy and promoting social mobility, with a sizable percentage of the population employed by the public sector (roughly 30% of the work force in areas such as healthcare, education, and government), and a corporatist system with a high percentage of the workforce unionized and involving a tripartite arrangement, where representatives of labour and employers negotiate wages and labour market policy is mediated by the government. As of 2020, all of the Nordic countries rank highly on the inequality-adjusted HDI and the Global Peace Index as well as being ranked in the top 10 on the World Happiness Report.

Although it was developed in the 1930s under the leadership of social democrats, the Nordic model began to gain attention after World War II. It has transformed in some ways over the last few decades, including increased deregulation and expanding privatization of public services, but is still distinguished from other models by the strong emphasis on public services and social investment.

Overview and aspects

The Nordic model has been characterized as follows:

- An elaborate social safety net, in addition to public services such as free education and universal healthcare in a largely tax-funded system.

- Strong property rights, contract enforcement and overall ease of doing business.

- Public pension plans.

- High levels of democracy as seen in the Freedom in the World survey and Democracy Index.

- Free trade combined with collective risk sharing (welfare social programmes and labour market institutions) which has provided a form of protection against the risks associated with economic openness.

- Little product market regulation. Nordic countries rank very high in product market freedom according to OECD rankings.

- Low levels of corruption. In Transparency International's 2019 Corruption Perceptions Index, Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden were ranked among the top 10 least corrupt of the 179 countries evaluated.

- A partnership between employers, trade unions and the government, whereby these social partners negotiate the terms to regulating the workplace amongst themselves, rather than the terms being imposed by law. Sweden has decentralised wage co-ordination while Finland is ranked the least flexible. The changing economic conditions have given rise to fear among workers as well as resistance by trade unions in regards to reforms.

- High trade union density and collective bargaining coverage. In 2019, trade union density was 90.7% in Iceland, 67.0% in Denmark, 65.2% in Sweden, 58.8% in Finland, and 50.4% in Norway; in comparison, trade union density was 16.3% in Germany and 9.9% in the United States. Additionally, in 2018, collective bargaining coverage was 90% in Iceland, 88.8% in Finland (2017), 88% in Sweden, 82% in Denmark, and 69% in Norway; in comparison collective bargaining coverage was 54% in Germany and 11.7% in the United States. The lower union density in Norway is mainly explained by the absence of a Ghent system since 1938. In contrast, Denmark, Finland and Sweden all have union-run unemployment funds.

- The Nordic countries received the highest ranking for protecting workers rights on the International Trade Union Confederation 2014 Global Rights Index, with Denmark being the only nation to receive a perfect score.

- Sweden at 56.6% of GDP, Denmark at 51.7%, and Finland at 48.6% reflect very high public spending. Public expenditure for health and education is significantly higher in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden in comparison to the OECD average.

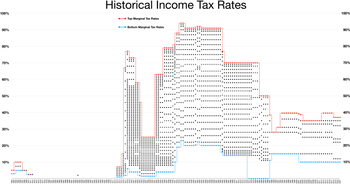

- Overall tax burdens as a percentage of GDP are high, with Denmark at 45.9% and both Finland and Sweden at 44.1%. The Nordic countries have relatively flat tax rates, meaning that even those with medium and low incomes are taxed at relatively high levels.

- The United Nations World Happiness Reports show that the happiest nations are concentrated in Northern Europe. The Nordics ranked highest on the metrics of real GDP per capita, healthy life expectancy, having someone to count on, perceived freedom to make life choices, generosity and freedom from corruption. The Nordic countries place in the top 10 of the World Happiness Report 2018, with Finland and Norway taking the top spots.

Economic system

The Nordic model is underpinned by a mixed-market capitalist economic system that features high degrees of private ownership, with the exception of Norway which includes a large number of state-owned enterprises and state ownership in publicly listed firms.

The Nordic model is described as a system of competitive capitalism combined with a large percentage of the population employed by the public sector, which amounts to roughly 30% of the work force, in areas such as healthcare and higher education. In Norway, Finland, and Sweden, many companies and/or industries are state-run or state-owned like utilities, mail, rail transport, airlines, electrical power industry, fossil fuels, chemical industry, steel mill, electronics industry, machine industry, aerospace manufacturer, shipbuilding, and the arms industry. In 2013, The Economist described its countries as "stout free-traders who resist the temptation to intervene even to protect iconic companies", while also looking for ways to temper capitalism's harsher effects and declared that the Nordic countries "are probably the best-governed in the world." Some economists have referred to the Nordic economic model as a form of "cuddly capitalism", with low levels of inequality, generous welfare states, and reduced concentration of top incomes, contrasting it with the more "cut-throat capitalism" of the United States, which has high levels of inequality and a larger concentration of top incomes, among others social inequalities.

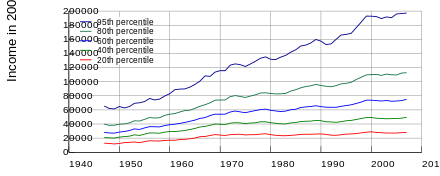

As a result of the Sweden financial crisis of 1990–1994, Sweden implemented economic reforms that were focused on deregulation, decentralization of wage bargaining, and the strengthening of competition laws. Despite being one of the most equal OECD nations, from 1985 to the 2010s Sweden saw the largest growth in income inequality among OECD economies. Other effects of the 1990s reforms was the substantial growth of mutual fund savings, which largely began with the government subsidizing mutual fund savings through the so-called Allemansfonder program in the 1980s; today 4 out of 5 people aged 18–74 have fund savings.

Norway's particularities

The state of Norway has ownership stakes in many of the country's largest publicly listed companies, owning 37% of the Oslo stock market and operating the country's largest non-listed companies, including Equinor and Statkraft. In January 2013, The Economist reported that "after the second world war the government nationalised all German business interests in Norway and ended up owning 44% of Norsk Hydro's shares. The formula of controlling business through shares rather than regulation seemed to work well, so the government used it wherever possible. 'We invented the Chinese way of doing things before the Chinese', says Torger Reve of the Norwegian Business School." The government also operates a sovereign wealth fund, the Government Pension Fund of Norway, whose partial objective is to prepare Norway for a post-oil future but "unusually among oil-producing nations, it is also a big advocate of human rights—and a powerful one, thanks to its control of the Nobel peace prize."

Norway is the only major economy in the West where younger generations are getting richer, with a 13% increase in disposable income for 2018, bucking the trend seen in other Western nations of Millennials becoming poorer than the generations which came before.

Lutheran influence

Some academics have theorized that Lutheranism, the dominant traditional religion of the Nordic countries, had an effect on the development of social democracy there. Schröder posits that Lutheranism promoted the idea of a nationwide community of believers and led to increased state involvement in economic and social life, allowing for nationwide welfare solidarity and economic co-ordination. Esa Mangeloja says that the revival movements helped to pave the way for the modern Finnish welfare state. During that process, the church lost some of its most important social responsibilities (health care, education, and social work) as these tasks were assumed by the secular Finnish state. Pauli Kettunen presents the Nordic model as the outcome of a sort of mythical "Lutheran peasant enlightenment", portraying the Nordic model as the result of a sort of "secularized Lutheranism"; however, mainstream academic discourse on the subject focuses on "historical specificity", with the centralized structure of the Lutheran church being but one aspect of the cultural values and state structures that led to the development of the welfare state in Scandinavia.

Labour market policy

The Nordic countries share active labour market policies as part of a social corporatist economic model intended to reduce conflict between labour and the interests of capital. This corporatist system is most extensive in Norway and Sweden, where employer federations and labour representatives bargain at the national level mediated by the government. Labour market interventions are aimed at providing job retraining and relocation.

The Nordic labour market is flexible, with laws making it easy for employers to hire and shed workers or introduce labour-saving technology. To mitigate the negative effect on workers, the government labour market policies are designed to provide generous social welfare, job retraining and relocation services to limit any conflicts between capital and labour that might arise from this process.

Nordic welfare model

The Nordic welfare model refers to the welfare policies of the Nordic countries, which also tie into their labour market policies. The Nordic model of welfare is distinguished from other types of welfare states by its emphasis on maximising labour force participation, promoting gender equality, egalitarian, and extensive benefit levels, the large magnitude of income redistribution and liberal use of expansionary fiscal policy.

While there are differences among the Nordic countries, they all share a broad commitment to social cohesion, a universal nature of welfare provision in order to safeguard individualism by providing protection for vulnerable individuals and groups in society, and maximising public participation in social decision-making. It is characterized by flexibility and openness to innovation in the provision of welfare. The Nordic welfare systems are mainly funded through taxation.

Despite the common values, the Nordic countries take different approaches to the practical administration of the welfare state. Denmark features a high degree of private sector provision of public services and welfare, alongside an assimilation immigration policy. Iceland's welfare model is based on a "welfare-to-work" (see workfare) model while part of Finland's welfare state includes the voluntary sector playing a significant role in providing care for the elderly. Norway relies most extensively on public provision of welfare.

Gender equality

When it comes to gender equality, the Nordic countries hold one of the smallest gaps in gender employment inequality of all OECD countries, with less than 8 points in all Nordic countries according to International Labour Organization standards. They have been at the front of the implementation of policies that promote gender equality; the Scandinavian governments were some of the first to make it unlawful for companies to dismiss women on grounds of marriage or motherhood. Mothers in Nordic countries are more likely to be working mothers than in any other region and families enjoy pioneering legislation on parental leave policies that compensate parents for moving from work to home to care for their child, including fathers. Although the specifics of gender equality policies in regards to the work place vary from country to country, there is a widespread focus in Nordic countries to highlight "continuous full-time employment" for both men and women as well as single parents as they fully recognize that some of the most salient gender gaps arise from parenthood. Aside from receiving incentives to take shareable parental leave, Nordic families benefit from subsidized early childhood education and care and activities for out-of-school hours for those children that have enrolled in full-time education.

The Nordic countries have been at the forefront of championing gender equality and this has been historically shown by substantial increases in women's employment. Between 1965 and 1990, Sweden's employment rate for women in working-age (15–64) went from 52.8% to 81.0%. In 2016, nearly three out of every four women in working-age in the Nordic countries were taking part in paid work. Nevertheless, women are still the main users of the shareable parental leave (fathers use less than 30% of their paid parental-leave-days), foreign women are being subjected to under-representation, and Finland still holds a notable gender pay-gap; the average woman's salary is 83% of that of a man, not accounting for confounding factors such as career choice.

Poverty reduction

The Nordic model has been successful at significantly reducing poverty. In 2011, poverty rates before taking into account the effects of taxes and transfers stood at 24.7% in Denmark, 31.9% in Finland, 21.6% in Iceland, 25.6% in Norway, and 26.5% in Sweden. After accounting for taxes and transfers, the poverty rates for the same year became 6%, 7.5%, 5.7%, 7.7% and 9.7% respectively, for an average reduction of 18.7 p.p. Compared to the United States, which has a poverty level pre-tax of 28.3% and post-tax of 17.4% for a reduction of 10.9 p.p., the effects of tax and transfers on poverty in all the Nordic countries are substantially bigger. In comparison to France (27 p.p. reduction) and Germany (24.2 p.p. reduction), the taxes and transfers in the Nordic countries are smaller on average.

Social democracy

Social democrats have played a pivotal role in shaping the Nordic model, with policies enacted by social democrats being pivotal in fostering the social cohesion in the Nordic countries. Among political scientists and sociologists, the term social democracy has become widespread to describe the Nordic model due to the influence of social democratic party governance in Sweden and Norway, in contrast to other classifications such as Christian democratic, liberal, Mediterranean, radical, and hybrid, based on consistency levels ("pure", "medium-high consistency" and "medium consistency"). According to sociologist Lane Kenworthy, the meaning of social democracy in this context refers to a variant of capitalism based on the predominance of private property and market allocation mechanisms alongside a set of policies for promoting economic security and opportunity within the framework of a capitalist economy as opposed to a political ideology that aims to replace capitalism.

While countries such as Austria, Belgium, Canada, France, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom have been categorized as social democratic at least once, the Nordic countries have been the only ones to be constantly categorized as such. In a review by Emanuele Ferragina and Martin Seeleib-Kaiser of works about the different models of welfare states, apart from Belgium and the Netherlands, categorized as "medium-high socialism", the Scandinavian countries analyzed (Denmark, Norway, and Sweden) were the only ones to be categorized by sociologist Gøsta Esping-Andersen as "high socialism", which is defined as socialist attributes and values (equality and universalism) and the social democratic model, which is characterized by "a high level of decommodification and a low degree of stratification. Social policies are perceived as 'politics against the market.'" They summarized the social democratic model as being based on "the principle of universalism, granting access to benefits and services based on citizenship. Such a welfare state is said to provide a relatively high degree of autonomy, limiting the reliance on family and market."

As of the 1990s, the Nordic identity has been explained with cultural, not political factors; by the 2010s, politics has been re-entering the conversation on the Nordic identity. According to Johan Strang, cultural explanation benefits neoliberalism, during whose rise the cultural phenomenon coincided. Strang states that "[t]he Social Democratic model, which was still very much alive during the Cold War, has now been abandoned, and other explanations for Nordic success have been sought to replace it."

History

The Nordic model traces its foundation to the "grand compromise" between workers and employers spearheaded by farmer and worker parties in the 1930s. Following a long period of economic crisis and class struggle, the "grand compromise" served as the foundation for the post-World War II Nordic model of welfare and labour market organization. The key characteristics of the Nordic model were the centralized coordination of wage negotiation between employers and labour organizations, termed a social partnership, as well as providing a peaceful means to address class conflict between capital and labour.

Magnus Bergli Rasmussen has challenged that farmers played an important role in ushering Nordic welfare states. A 2022 study by him found that farmers had strong incentives to resist welfare state expansion and farmer MPs consistently opposed generous welfare policies.

Although often linked to social democratic governance, the Nordic model's parentage also stems from a mixture of mainly social democratic, centrist, and right-wing political parties, especially in Finland and Iceland, along with the social trust that emerged from the "great compromise" between capital and labour. The influence of each of these factors on each Nordic country varied as social democratic parties played a larger role in the formation of the Nordic model in Sweden and Norway, whereas in Iceland and Finland right-wing political parties played a much more significant role in shaping their countries' social models.

Social security and collective wage bargaining policies were rolled back following economic imbalances in the 1980s and the financial crises of the 1990s which led to more restrictive budgetary policies that were most pronounced in Sweden and Iceland. Nonetheless, welfare expenditure remained high in these countries, compared to the European average.

Denmark

Social welfare reforms emerged from the Kanslergade Agreement of 1933 as part of a compromise package to save the Danish economy. Denmark was the first Nordic country to join the European Union in the 1970s, reflecting the different political approaches to it among the Nordic countries.

Finland

The early 1990s recession affected the Nordic countries and caused a deep crisis in Finland, and came amid the context of the dissolution of the Soviet Union and collapse of trade from the Eastern Bloc. Like in Sweden, Finland's universalistic welfare state based on the Nordic model was weakened and no longer based on the social-democratic middle ground, as several social welfare policies were often permanently dismantled; however, Finland was hit even harder than Sweden. During the crisis, Finland looked to the European Union, which they were more committed and open to joining than Sweden and especially Norway, while Denmark had already joined the EU by the 1970s.

Iceland

According to analyst Harpa Njálsdóttir, Iceland in the late 2010s moved away from the Nordic model towards the economic liberal model of workfare. She also noted that with the large changes having been made to the social security system, "70% of elderly people now live well below national subsistence criteria, while about 70% of those who live alone and in bad conditions are women."

Norway

Norway's "grand compromise" emerged as a response to the crisis of the early 1930s between the trade union confederation and Norwegian Employers' Association, agreeing on national standards in labour–capital relations and creating the foundation for social harmony throughout the period of compromises. For a period between the 1980s and the 1990s, Norway underwent more neoliberal reforms and marketization than Sweden during the same time frame, while still holding to the traditional foundations of the "social democratic compromise" that was specific to Western capitalism from 1945 to 1973.

Norway was the Nordic country least willing to join the European Union. While Finland and Sweden suffered greatly from the 1990s recession, Norway began to earn enough revenue from their oil. As of 2007, the Norwegian state maintained large ownership positions in key industrial sectors, among them petroleum, natural gas, minerals, lumber, seafood and fresh water. The petroleum industry accounts for around a quarter of the country's gross domestic product.

Sweden

In Sweden, the grand compromise was pushed forward by the Saltsjöbaden Agreement signed by employer and trade union associations at the seaside retreat of Saltsjöbaden in 1938. This agreement provided the foundation for Scandinavian industrial relations throughout Europe's Golden Age of Capitalism. The Swedish model of capitalism developed under the auspices of the Swedish Social Democratic Party which assumed power in 1932 and retained uninterrupted power until 1976. Initially differing very little from other industrialized capitalist countries, the state's role in providing comprehensive welfare and infrastructure expanded after the Second World War until reaching a broadly social democratic consensus in the 1950s which would become known as the social liberal paradigm, which was followed by the neoliberal paradigm by the 1980s and 1990s. According to Phillip O'Hara, "Sweden eventually became part of the Great Capitalist Restoration of the 1980s and 1990s. In all the industrial democracies and beyond, this recent era has seen the retrenchment of the welfare state by reduced social spending in real terms, tax cuts, deregulation and privatization, and a weakening of the influence of organized labor."

In the 1950s, Olof Palme and the prime minister Tage Erlander formulated the basis of Swedish social democracy and what would become known as the "Swedish model", drawing inspiration from the reformist socialism of party founder Hjalmar Branting, who stated that socialism "would not be created by brutalized...slaves [but by] the best positioned workers, those who have gradually obtained a normal workday, protective legislation, minimum wages." Arguing against those to their left, the party favored moderatism and wanted to help workers in the here and now, and followed the Fabian argument that the policies were steps on the road to socialism, which would not come about through violent revolution but through the social corporative model of welfare capitalism, to be seen as progressive in providing institutional legitimacy to the labour movement by recognizing the existence of the class conflict between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat as a class compromise within the context of existing class conflict. This Swedish model was characterized by a strong labour movement as well as inclusive publicly funded and often publicly administered welfare institutions.

By the early 1980s, the Swedish model began to suffer from international imbalances, declining competitiveness and capital flight. Two polar opposite solutions emerged to restructure the Swedish economy, the first being a transition to socialism by socializing the ownership of industry and the second providing favorable conditions for the formation of private capital by embracing neoliberalism. The Swedish model was first challenged in 1976 by the Meidner Plan promoted by the Swedish Trade Union Confederation and trade unions which aimed at the gradual socialization of Swedish companies through wage earner funds. The Meidner Plan aimed to collectivize capital formation in two generations by having the wage earner funds own predominant stakes in Swedish corporations on behalf of workers. This proposal was supported by Palme and the Social Democratic party leadership, but it did not garner enough support upon Palme's assassination and was defeated by the conservatives in the 1991 Swedish general election.

Upon returning to power in 1982, the Social Democratic party inherited a slowing economy resulting from the end of the post-war boom. The Social Democrats adopted monetarist and neoliberal policies, deregulating the banking industry, and liberalizing currency in the 1980s. The economic crisis of the 1990s saw greater austerity measures, deregulation, and the privatization of public services. Into the 21st century, it greatly affected Sweden and its universalistic welfare state, although not as hard as Finland. Sweden remained more Eurosceptic than Finland, and its struggles affected all the other Nordic countries, as it was seen as "the guiding star of the north", and with Sweden fading away, other Nordic countries also felt like they were losing their political identities. When the Nordic model was then gradually rediscovered, cultural explanations were sought for the special features of the Nordic countries.

Reception

The Nordic model has been positively received by some American politicians and political commentators. Jerry Mander has likened the Nordic model to a kind of "hybrid" system which features a blend of capitalist economics with socialist values, representing an alternative to American-style capitalism. Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders has pointed to Scandinavia and the Nordic model as something the United States can learn from, in particular with respect to the benefits and social protections the Nordic model affords workers and its provision of universal healthcare.

According to Luciano Pellicani, the social and political measures adopted in countries like Sweden and Denmark are the same that some other European left-wing politicians theorised to combine justice and freedom, referring to liberal socialism and movements like Giustizia e Libertà and Fabian Society. According to Naomi Klein, former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev sought to move the Soviet Union in a similar direction to the Nordic system, combining free markets with a social safety net, but still retaining public ownership of key sectors of the economy—ingredients that he believed would transform the Soviet Union into "a socialist beacon for all mankind."

The Nordic model has also been positively received by various social scientists and economists. American professor of sociology and political science Lane Kenworthy advocates for the United States to make a gradual transition toward a social democracy similar to those of the Nordic countries, defining social democracy as such: "The idea behind social democracy was to make capitalism better. There is disagreement about how exactly to do that, and others might think the proposals in my book aren't true social democracy. But I think of it as a commitment to use government to make life better for people in a capitalist economy. To a large extent, that consists of using public insurance programs—government transfers and services."

Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz says that there is higher social mobility in the Scandinavian countries than in the United States and posits that Scandinavia is now the land of opportunity that the United States once was. American author Ann Jones, who lived in Norway for four years, posits that "the Nordic countries give their populations freedom from the market by using capitalism as a tool to benefit everyone" whereas in the United States "neoliberal politics puts the foxes in charge of the henhouse, and capitalists have used the wealth generated by their enterprises (as well as financial and political manipulations) to capture the state and pluck the chickens."

Economist Jeffrey Sachs is a proponent of the Nordic model, having pointed out that the Nordic model is "the proof that modern capitalism can be combined with decency, fairness, trust, honesty, and environmental sustainability." The Nordic combination of extensive public provision of welfare and a culture of individualism has been described by Lars Trägårdh of Ersta Sköndal University College as "statist individualism." A 2016 survey by the think tank Israel Democracy Institute found that nearly 60 percent of Israeli Jews preferred a "Scandinavian model" economy, with high taxes and a robust welfare state.

Criticism

Socialist economists Pranab Bardhan and John Roemer criticize Nordic-style social democracy for its questionable effectiveness in promoting relative egalitarianism as well as its sustainability. They posit that Nordic social democracy requires a strong labour movement to sustain the heavy redistribution required, arguing that it is idealistic to think similar levels of redistribution can be accomplished in countries with weaker labour movements. They say that even in the Scandinavian countries social democracy has been in decline since the weakening of the labour movement in the early 1990s, arguing that the sustainability of social democracy is limited. Roemer and Bardham posit that establishing a market-based socialist economy by changing enterprise ownership would be more effective than social democratic redistribution at promoting egalitarian outcomes, particularly in countries with weak labour movements.

Historian Guðmundur Jónsson said that it would be historically inaccurate to include Iceland in one aspect of the Nordic model, that of consensus democracy. Addressing the time period from 1950 to 2000, Jónsson writes that "Icelandic democracy is better described as more adversarial than consensual in style and practice. The labour market was rife with conflict and strikes more frequent than in Europe, resulting in strained government–trade union relationship. Secondly, Iceland did not share the Nordic tradition of power-sharing or corporatism as regards labour market policies or macro-economic policy management, primarily because of the weakness of Social Democrats and the Left in general. Thirdly, the legislative process did not show a strong tendency towards consensus-building between government and opposition with regard to government seeking consultation or support for key legislation. Fourthly, the political style in legislative procedures and public debate in general tended to be adversarial rather than consensual in nature."

In a 2017 study, economists James Heckman and Rasmus Landersøn compared American and Danish social mobility, and found that social mobility is not as high as figures might suggest in the Nordic countries, although they did find that Denmark ranks higher in income mobility. When looking exclusively at wages (before taxes and transfers), Danish and American social mobility are very similar; it is only after taxes and transfers are taken into account that Danish social mobility improves, indicating that Danish economic redistribution policies are the key drivers of greater mobility. Additionally, Denmark's greater investment in public education did not improve educational mobility significantly, meaning children of non-college educated parents are still unlikely to receive college education, although this public investment did result in improved cognitive skills amongst poor Danish children compared to their American peers. There was evidence that generous welfare policies could discourage the pursuit of higher-level education due to decreasing the economic benefits that college education level jobs offer and increasing welfare for workers of a lower education level.

Some welfare and gender researchers based in the Nordic countries suggest that these states have often been over-privileged when different European societies are being assessed in terms of how far they have achieved gender equality. They posit that such assessments often utilise international comparisons adopting conventional economic, political, educational, and well-being measures. By contrast, they suggest that if one takes a broader perspective on well-being incorporating, such as social issues associated with bodily integrity or bodily citizenship, then some major forms of men's domination still stubbornly persist in the Nordic countries, e.g. business, violence to women, sexual violence to children, the military, academia, and religion.

While praising the Nordic model as a "clear and compelling contrast to the neoliberal ideology that has strafed the rest of the world with inequality, ill-health and needless poverty," economic anthropologist Jason Hickel sharply criticizes the "ecological disaster" that accompanies it, noting that data shows the Nordic countries "have some of the highest levels of resource use and CO2 emissions in the world, in consumption based terms, drastically overshooting safe planetary boundaries," and rank towards the bottom of the Sustainable Development Index. He argues that the model needs to be updated for the Anthropocene, and reduce overconsumption while retaining the positive elements of progressive social democracy including universal healthcare and education, paid vacations and reasonable working hours, which have resulted in much better health outcomes and poverty reduction compared to overtly neoliberal countries like the United States, in order to "stand as a beacon for the rest of the world in the 21st century."

Misconceptions

George Lakey, author of Viking Economics, says that Americans generally misunderstand the nature of the Nordic model, commenting: "Americans imagine that "welfare state" means the U.S. welfare system on steroids. Actually, the Nordics scrapped their American-style welfare system at least 60 years ago, and substituted universal services, which means everyone—rich and poor—gets free higher education, free medical services, free eldercare, etc."

In a speech at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government, Lars Løkke Rasmussen, the centre-right Danish prime minister from the conservative-liberal Venstre party, addressed the American misconception that the Nordic model is a form of socialism, which is conflated with any form of planned economy, stating: "I know that some people in the US associate the Nordic model with some sort of socialism. Therefore, I would like to make one thing clear. Denmark is far from a socialist planned economy. Denmark is a market economy."