Historicism is a method of interpretation in Christian eschatology which associates biblical prophecies with actual historical events and identifies symbolic beings with historical persons or societies; it has been applied to the Book of Revelation by many writers. The Historicist view follows a straight line of continuous fulfillment of prophecy which starts in Daniel's time and goes through John of Patmos' writing of the Book of Revelation all the way to the Second Coming of Jesus Christ.

One of the most influential aspects of the early Protestant historicist paradigm was the assertion that scriptural identifiers of the Antichrist were matched only by the institution of the Papacy. Particular significance and concern were the Papal claims of authority over the Church through Apostolic Succession, and the State through the Divine Right of Kings. When the Papacy aspires to exercise authority beyond its religious realm into civil affairs, on account of the Papal claim to be the Vicar of Christ, then the institution was fulfilling the more perilous biblical indicators of the Antichrist. Martin Luther wrote this view into the Smalcald Articles of 1537; this view was not novel and had been leveled at various popes throughout the centuries, even by Roman Catholic saints. It was then widely popularized in the 16th century, via sermons, drama, books, and broadside publication. The alternate methods of prophetic interpretation, Futurism and Preterism were derived from Jesuit writings, whose counter-reformation efforts were aimed at opposing this interpretation that the Antichrist was the Papacy or the power of the Roman Catholic Church.

Origins in Judaism and Early Church

The interpreters using the historicist approach for the Book of Revelation had their origins in the Jewish apocalyptic writings, such as those in the Book of Daniel, which predicted the future time between their writing and the end of the world. Throughout most of history since the predictions of the book of Daniel, historicism has been widely used. This approach can be found in the works of Josephus, who interpreted the fourth kingdom of Daniel 2 as the Roman empire with a future power as the stone "not cut by human hands", that would overthrow the Romans. It is also found in the early church in the works of Irenaeus and Tertullian, who interpreted the fourth kingdom of Daniel as the Roman empire and believed that in the future it was going to be broken up into smaller kingdoms, as the iron mixed with clay, and in the writings of Clement of Alexandria and Jerome, as well as other well-known church historians and scholars of the early church. But it has been associated particularly with Protestantism and the Reformation. It was the standard interpretation of the Lollard movement, which was regarded as the precursor to the Protestant Reformation, and it was known as the Protestant interpretation until modern times.

Antichrist

Church Fathers

The Church Fathers who interpreted the Biblical prophecy historistically were: Justin Martyr, who wrote about the Antichrist: "He whom Daniel foretells would have dominion for a time and times and an half, is even now at the door"; Irenaeus, who wrote in Against Heresies about the coming of the Antichrist: "This Antichrist shall ... devastate all things ... But then, the Lord will come from Heaven on the clouds ... for the righteous"; Tertullian, looking to the Antichrist, wrote: "He is to sit in the temple of God, and boast himself as being god. In our view, he is Antichrist as taught us in both the ancient and the new prophecies; and especially by the Apostle John, who says that 'already many false-prophets are gone out into the world' as the fore-runners of Antichrist"; Hippolytus of Rome, in his Treatise on Christ and Antichrist, wrote: "As Daniel also says (in the words) 'I considered the Beast, and look! There were ten horns behind it – among which shall rise another (horn), an offshoot, and shall pluck up by the roots the three (that were) before it.' And under this, was signified none other than Antichrist"; Athanasius of Alexandria clearly held to the historical view in his many writings, writing in The Deposition of Arius: "I addressed the letter to Arius and his fellows, exhorting them to renounce his impiety.... There have gone forth in this diocese at this time certain lawless men – enemies of Christ – teaching an apostasy which one may justly suspect and designate as a forerunner of Antichrist"; Jerome wrote: "Says the apostle [Paul in the Second Epistle to the Thessalonians], 'Unless the Roman Empire should first be desolated, and antichrist proceed, Christ will not come.'" Jerome claimed that the time of the break-up of Rome, as predicted in Daniel 2, had begun even in his time. He also identifies the Little horn of Daniel 7:8 and 7:24–25 which "shall speak words against the Most High, and shall wear out the saints of the Most High, and shall think to change the times and the law" as the Papacy.

Protestant view of the Papacy as the Antichrist

Protestant Reformers, including John Wycliffe, Martin Luther, John Calvin, Thomas Cranmer, John Thomas, John Knox, Roger Williams, Cotton Mather, Jonathan Edwards, and John Wesley, as well as most Protestants of the 16th–18th centuries, felt that the Early Church had been led into the Great Apostasy by the Papacy and identified the Pope with the Antichrist. The Centuriators of Magdeburg, a group of Lutheran scholars in Magdeburg headed by Matthias Flacius, wrote the 12-volume Magdeburg Centuries to discredit the Catholic Church and lead other Christians to recognize the Pope as the Antichrist. So, rather than expecting a single Antichrist to rule the earth during a future Tribulation period, Martin Luther, John Calvin, and other Protestant Reformers saw the Antichrist as a present feature in the world of their time, fulfilled in the Papacy. Like most Protestant theologians of his time, Isaac Newton believed that the Papal Office (and not any one particular Pope) was the fulfillment of the Biblical predictions about Antichrist, whose rule is prophesied to last for 1,260 years.

The Protestant Reformers tended to believe that the Antichrist power would be revealed so that everyone would comprehend and recognize that the Pope is the real, true Antichrist and not the vicar of Christ. Doctrinal works of literature published by the Lutherans, the Reformed Churches, the Presbyterians, the Baptists, the Anabaptists, and the Methodists contain references to the Pope as the Antichrist, including the Smalcald Articles, Article 4 (1537), the Treatise on the Power and Primacy of the Pope written by Philip Melanchthon (1537), the Westminster Confession, Article 25.6 (1646), and the 1689 Baptist Confession of Faith, Article 26.4. In 1754, John Wesley published his Explanatory Notes Upon the New Testament, which is currently an official Doctrinal Standard of the United Methodist Church. In his notes on the Book of Revelation (chapter 13), Wesley commented: "The whole succession of Popes from Gregory VII are undoubtedly Antichrists. Yet this hinders not, but that the last Pope in this succession will be more eminently the Antichrist, the Man of Sin, adding to that of his predecessors a peculiar degree of wickedness from the bottomless pit."

In calling the pope the "Antichrist", the early Lutherans stood in a tradition that reached back into the eleventh century. Not only dissidents and heretics but even saints had called the bishop of Rome the "Antichrist" when they wished to castigate his abuse of power. What Lutherans understood as a papal claim to unlimited authority over everything and everyone reminded them of the apocalyptic imagery of Daniel 11, a passage that even prior to the Reformation had been applied to the pope as the Antichrist of the last days.

The identification of the Pope with the Antichrist was so ingrained in the Reformation Era, that Luther himself stated it repeatedly:

"This teaching [of the supremacy of the pope] shows forcefully that the Pope is the very Antichrist, who has exalted himself above, and opposed himself against Christ, because he will not permit Christians to be saved without his power, which, nevertheless, is nothing, and is neither ordained nor commanded by God".

and,

"nothing else than the kingdom of Babylon and of the very Antichrist. For who is the man of sin and the son of perdition, but he who by his teaching and his ordinances increases the sin and perdition of souls in the church; while he yet sits in the church as if he were God? All these conditions have now for many ages been fulfilled by the papal tyranny."

John Calvin similarly wrote:

"Though it be admitted that Rome was once the mother of all Churches, yet from the time when it began to be the seat of Antichrist it has ceased to be what it was before. Some persons think us too severe and censorious when we call the Roman Pontiff Antichrist. But those who are of this opinion do not consider that they bring the same charge of presumption against Paul himself, after whom we speak and whose language we adopt .. I shall briefly show that (Paul's words in II Thess. 2) are not capable of any other interpretation than that which applies them to the Papacy."

John Knox wrote on the Pope:

"Yea, to speak it in plain words; lest that we submit ourselves to Satan, thinking that we submit ourselves to Jesus Christ, for, as for your Roman kirk, as it is now corrupted, and the authority thereof, whereon stands the hope of your victory, I no more doubt but that it is the synagogue of Satan, and the head thereof, called the pope, to be that man of sin, of whom the apostle speaks."

Thomas Cranmer on the Antichrist wrote:

"Whereof it followeth Rome to be the seat of Antichrist, and the pope to be very antichrist himself. I could prove the same by many other scriptures, old writers, and strong reasons."

John Wesley, speaking of the identity given in the Bible of the Antichrist, wrote:

"In many respects, the Pope has an indisputable claim to those titles. He is, in an emphatical sense, the man of sin, as he increases all manner of sin above measure. And he is, too, properly styled, the son of perdition, as he has caused the death of numberless multitudes, both of his opposers and followers, destroyed innumerable souls, and will himself perish everlastingly. He it is that opposeth himself to the emperor, once his rightful sovereign; and that exalteth himself above all that is called God, or that is worshipped – Commanding angels, and putting kings under his feet, both of whom are called gods in scripture; claiming the highest power, the highest honour; suffering himself, not once only, to be styled God or vice-God. Indeed no less is implied in his ordinary title, "Most Holy Lord," or, "Most Holy Father." So that he sitteth – Enthroned. In the temple of God – Mentioned Rev. xi, 1. Declaring himself that he is God – Claiming the prerogatives which belong to God alone."

Roger Williams wrote about the Pope:

"the pretended Vicar of Christ on earth, who sits as God over the Temple of God, exalting himself not only above all that is called God, but over the souls and consciences of all his vassals, yea over the Spirit of Christ, over the Holy Spirit, yea, and God himself ... speaking against the God of heaven, thinking to change times and laws; but he is the Son of Perdition."

The identification of the Roman Catholic Church as the apostate power written of in the Bible as the Antichrist became evident to many as the Reformation began, including John Wycliffe, who was well-known throughout Europe for his opposition to the doctrine and practices of the Catholic Church, which he believed had clearly deviated from the original teachings of the early Church and to be contrary to the Bible. Wycliffe himself tells (Sermones, III. 199) how he concluded that there was a great contrast between what the Church was and what it ought to be, and saw the necessity for reform. Along with John Hus, they had started the inclination toward ecclesiastical reforms of the Catholic Church.

When the Swiss Reformer Huldrych Zwingli became the pastor of the Grossmünster in Zurich in 1518, he began to preach ideas on reforming the Catholic Church. Zwingli, who was a Catholic priest before he became a Reformer, often referred to the Pope as the Antichrist. He wrote: "I know that in it works the might and power of the Devil, that is, of the Antichrist".

The English Reformer William Tyndale held that while the Roman Catholic realms of that age were the empire of Antichrist, any religious organization that distorted the doctrine of the Old and New Testaments also showed the work of Antichrist. In his treatise The Parable of the Wicked Mammon, he expressly rejected the established Church teaching that looked to the future for an Antichrist to rise up, and he taught that Antichrist is a present spiritual force that will be with us until the end of the age under different religious disguises from time to time. Tyndale's translation of 2 Thessalonians, chapter 2, concerning the "Man of Lawlessness" reflected his understanding, but was significantly amended by later revisers, including the King James Bible committee, which followed the Vulgate more closely.

In 1870, the newly formed Kingdom of Italy annexed the remaining Papal States, depriving the Pope of his temporal power. However, the Papal rule over Italy was later restored by the Italian Fascist regime (albeit on a greatly diminished scale) in 1929 as head of the Vatican City state; under Mussolini's dictatorship, Roman Catholicism became the State religion of Fascist Italy (see also Clerical fascism), and the Racial Laws were enforced to outlaw and persecute both Italian Jews and Protestant Christians, especially Evangelicals and Pentecostals. Thousands of Italian Jews and a small number of Protestants died in the Nazi concentration camps.

Today, many Protestant and Restorationist denominations still officially maintain that the Papacy is the Antichrist, such as the conservative Lutheran Churches and the Seventh-day Adventists. In 1988, Ian Paisley, Evangelical minister and founder of the Free Presbyterian Church of Ulster, made headlines with such a statement about Pope John Paul II. The Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod states about the Pope and the Catholic Church:

There are two principles that mark the papacy as the Antichrist. One is that the pope takes to himself the right to rule the church that belongs only to Christ. He can make laws forbidding the marriage of priests, eating or not eating meat on Friday, birth control, divorce and remarriage, even where there are not such laws in the Bible. The second is that he teaches that salvation is not by faith alone but by faith and works. The present pope upholds and practices these principles. This marks his rule as antichristian rule in the church. All popes hold the same office over the church and promote the same antichristian belief so they all are part of the reign of the Antichrist. The Bible does not present the Antichrist as one man for one short time, but as an office held by a man through successive generations. It is a title like King of England.

Other views

Some Franciscans had considered the Emperor Frederick II a positive Antichrist who would purify the Catholic Church from opulence, riches, and clergy.

Some of the debated features of the Reformation's Historicist interpretations reached beyond the Book of Revelation. They included the identification of:

- the Antichrist (1 and 2 John);

- the Beast of Revelation 13;

- the Man of Sin, or Man of Lawlessness, of 2 Thessalonians 2 (2:1–12);

- the "Little horn" of Daniel 7 and 8;

- The Abomination of desolation of Daniel 9, 11, and 12; and

- the Whore of Babylon of Revelation 17.

Seven churches

The non-separatist Puritan, Thomas Brightman, was the first to propose a historicist interpretation of the Seven Churches of Revelation 2–3. He outlined how the seven Churches represent the seven ages of the Church of Christ. A typical historicist view of the Church of Christ spans several periods of church history, each similar to the original church, as follows:

- The age of Ephesus is the apostolic age.

- The age of Smyrna is the persecution of the Church through AD 313.

- The age of Pergamus is the compromised Church lasting until AD 500.

- The age of Thyatira is the rise of the papacy to the Reformation.

- The age of Sardis is the age of the Reformation.

- The age of Philadelphia is the age of evangelism.

- The age of Laodicea is liberal churches in a "present day" context.

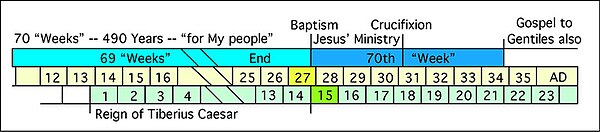

The age of Laodicea is typically identified as occurring in the same time period as the expositor. Brightman viewed the age of Laodicea as the England of his day. In the Millerite movement, each church represented a dateable period of ecclesiastical history. Thus, William Miller dated the age of Laodicea from 1798–1843, followed by the End of days in 1844.

The Roman Catholic priest Fr. E. Berry in his commentary writes: "The seven candlesticks represent the seven churches of Asia. As noted above, seven is the perfect number which denotes universality. Hence by extension the seven candlesticks represent all churches throughout the world for all time. Gold signifies the charity of Christ which pervades and vivifies the Church."

Seven seals

The traditional historicist view of the Seven Seals spanned the time period from John of Patmos to Early Christendom. Protestant scholars such as Campegius Vitringa, Alexander Keith, and Christopher Wordsworth did not limit the timeframe to the 4th century. Some have even viewed the opening of the Seals right into the early modern period.

Seventh-day Adventists view the first six seals as representing events that took place during the Christian era up until 1844. Contemporary-historicists view all of Revelation as it relates to John's own time, with the allowance of making some guesses about the future.

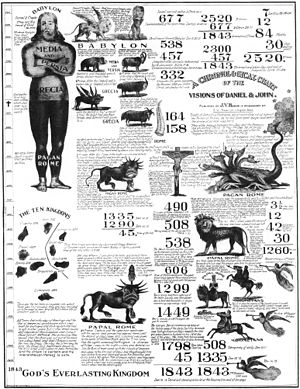

Seven trumpets

The classical historicist identifies the first four trumpets with the pagan invasions of Western Christendom in the 5th century AD (by the Visigoths, Vandals, Huns, and Heruli), while the fifth and sixth trumpets have been identified with the assault on Eastern Christendom by the Saracen armies and Turks during the Middle Ages. The symbolism of Revelation 6:12–13 is said by Adventists to have been fulfilled in the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, the dark day of 19 May 1780, and the Leonids meteor shower of 13 November 1833.

Vision of Chapter 10

The classical historicist view of the vision of the angel with the little book, in Revelation 10, represents the Protestant Reformation and the printing of Bibles in the common languages. The Adventists take a unique view applying it to the Millerite movement; the "bitterness" of the book (Rev 10:10) represents the Great Disappointment.

Two witnesses

The classical historicist view takes a number of different perspectives, including that the two witnesses are symbolic of two insular Christian movements, such as the Waldenses, or that the Reformers are meant, or the Old Testament and the New Testament. It is usually taught that Revelation 11 corresponds to the events of the French Revolution.

Beasts of Revelation

The historicist views of Revelation 12–13 concern prophecies about the forces of evil viewed to have occurred in the middle ages. The first beast of Revelation 13 (from the sea) is considered to be the pagan Rome and the Papacy, or more exclusively the latter.

In 1798, the French General Louis Alexandre Berthier exiled the Pope and took away all his authority, which was restored in 1813, destroyed again in 1870, and later restored in 1929. Adventists have taken this as fulfillment of the prophecy that the Beast of Revelation would receive a deadly wound but that the wound would be healed. They have attributed the wounding and resurgence in Revelation 13:3 to the papacy, referring to General Louis Berthier's capture of Pope Pius VI in 1798 and the pope's subsequent death in 1799.

Adventists believe that the second beast (from the earth) symbolizes the United States of America. The "image of the beast" represents Protestant churches who form an alliance with the Papacy, and the "mark of the beast" refers to a future universal Sunday law. Both Adventists and classical historicists view the Great whore of Babylon, in Revelation 17–18, as Roman Catholicism.

Number of the Beast

Adventists have interpreted the number of the beast, 666, as corresponding to the title Vicarius Filii Dei of the Pope. In 1866, Uriah Smith was the first to propose the interpretation to the Seventh-day Adventist Church. In The United States in the Light of Prophecy, he wrote:

The pope wears upon his pontifical crown in jeweled letters, this title: "Vicarius Filii Dei," "Viceregent of the Son of God;" [sic] the numerical value of which title is just six hundred and sixty-six. The most plausible supposition we have ever seen on this point is that here we find the number in question. It is the number of the beast, the papacy; it is the number of his name, for he adopts it as his distinctive title; it is the number of a man, for he who bears it is the "man of sin."

Prominent Adventist scholar J. N. Andrews also adopted this view. Uriah Smith maintained his interpretation in the various editions of Thoughts on Daniel and the Revelation, which was influential in the church.

Various documents from the Vatican contain wording such as "Adorandi Dei Filii Vicarius, et Procurator quibus numen aeternum summam Ecclesiae sanctae dedit", which translates to "As the worshipful Son of God's Vicar and Caretaker, to whom the eternal divine will has given the highest rank of the holy Church".

The New Testament was written in Koine Greek, and Adventists used Roman numerals to calculate the value of "Vicarius Filii Dei" whose word is in Latin language. "Vicarius Filii Dei" is Latin, and it does not exist in the New Testament, which was written in Koine Greek.

Samuele Bacchiocchi, an Adventist scholar, and the only Adventist to be awarded a gold medal by Pope Paul VI for the distinction of summa cum laude (Latin for "with highest praise"), has documented the pope using such a title:

We noted that contrary to some Catholic sources who deny the use of Vicarius Filii Dei as a papal title, we have found this title to have been used in official Catholic documents to support the ecclesiastical authority and temporal sovereignty of the pope. Thus the charge that Adventists fabricated the title to support their prophetic interpretation of 666, is unfair and untrue.

However, Bacchiocchi's general conclusion regarding the interpretation of Vicarius Filii Dei is that he, together with many current Adventist scholars, refrains from using only the calculation of papal names for the number 666:

The meaning of 666 is to be found not in the name or titles of influential people, but in its symbolic meaning of rebellion against God manifested in false worship. ... the true meaning of 666 is to be found not in external markings or on a pope's title, but in the allegiance to false worship promoted by satanic agencies represented by the dragon, the sea-beast, and the land beast.

Commentaries

Notable and influential commentaries by Protestant scholars having historicist views of the Book of Revelation were:

- Clavis Apocalyptica (1627), a commentary on The Apocalypse by Joseph Mede.

- Anacrisis Apocalypseos (1705), a commentary on The Apocalypse by Campegius Vitringa.

- Commentary on the Revelation of St. John (1720), a commentary on The Apocalypse by Charles Daubuz.

- The Signs of the Times (1832), a commentary on The Apocalypse by Rev. Dr. Alexander Keith.

- Horae Apocalypticae (1837), a commentary on The Apocalypse by Rev. Edward Bishop Elliott.

- Vindiciae Horariae (1848), twelve letters to the Rev. Dr. Keith, in reply to his strictures on the "Horae apocalypticae" by Rev. Edward Bishop Elliott.

- Lectures on the Apocalypse (1848), a commentary on The Apocalypse by Christopher Wordsworth.

- The Final Prophecy of Jesus (2007), An Historicist Introduction, Analysis, and Commentary on the Book of Revelation by Oral E. Collins, Ph.D.