| Typhoid fever | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Enteric fever, slow fever |

| |

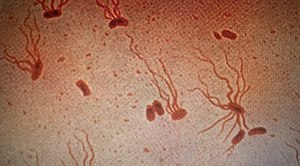

| Causative agent: Salmonella enterica serological variant Typhi (shown under a microscope with flagellar stain) | |

| Specialty | Infectious diseases |

| Symptoms | Fever that starts low and increases daily, possibly reaching as high as 104.9 °F (40.5 °C) Headache, weakness and fatigue, muscle aches, sweating, dry cough, loss of appetite, weight loss, stomach pain, diarrhea or constipation, rash, swollen stomach (enlarged liver or spleen) |

| Usual onset | 1–2 weeks after ingestion |

| Duration | Usually 7–10 days after antibiotic treatment begins. Longer if there are complications or drug resistance. |

| Causes | Gastrointestinal infection of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi |

| Risk factors | Living in or travel to areas where typhoid fever is established, Work as a clinical microbiologist handling Salmonella typhi bacteria, Have close contact with someone who is infected or has recently been infected with typhoid fever, Drink water polluted by sewage that contains Salmonella typhi |

| Prevention | Preventable by vaccine. Travelers to regions with higher typhoid prevalence are usually encouraged to get a vaccination before travel. |

| Treatment | Antibiotics, hydration, surgery in extreme cases. Quarantine to avoid exposing others (not commonly done in modern times). |

| Prognosis | Likely

to recover without complications if proper antibiotics administered and

diagnosed early. If infecting strain is multi-drug resistant or

extensively drug resistant then prognosis more difficult to determine.

Among untreated acute cases, 10% will shed bacteria for three months after initial onset of symptoms, and 2–5% will become chronic typhoid carriers. Some carriers are diagnosed by positive tissue specimen. Chronic carriers are by definition asymptomatic. |

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by Salmonella serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several days. This is commonly accompanied by weakness, abdominal pain, constipation, headaches, and mild vomiting. Some people develop a skin rash with rose colored spots. In severe cases, people may experience confusion. Without treatment, symptoms may last weeks or months. Diarrhea may be severe, but is uncommon. Other people may carry the bacterium without being affected, but they are still able to spread the disease. Typhoid fever is a type of enteric fever, along with paratyphoid fever. S. enterica Typhi is believed to infect and replicate only within humans.

Typhoid is caused by the bacterium Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhi growing in the intestines, peyers patches, mesenteric lymph nodes, spleen, liver, gallbladder, bone marrow and blood. Typhoid is spread by eating or drinking food or water contaminated with the feces of an infected person. Risk factors include limited access to clean drinking water and poor sanitation. Those who have not yet been exposed to the pathogen and ingest contaminated drinking water or food are most at risk for developing symptoms. Only humans can be infected; there are no known animal reservoirs.

Diagnosis is by culturing and identifying S. enterica Typhi from patient samples or detecting an immune response to the pathogen from blood samples. Recently, new advances in large-scale data collection and analysis have allowed researchers to develop better diagnostics, such as detecting changing abundances of small molecules in the blood that may specifically indicate typhoid fever. Diagnostic tools in regions where typhoid is most prevalent are quite limited in their accuracy and specificity, and the time required for a proper diagnosis, the increasing spread of antibiotic resistance, and the cost of testing are also hardships for under-resourced healthcare systems.

A typhoid vaccine can prevent about 40% to 90% of cases during the first two years. The vaccine may have some effect for up to seven years. For those at high risk or people traveling to areas where the disease is common, vaccination is recommended. Other efforts to prevent the disease include providing clean drinking water, good sanitation, and handwashing. Until an infection is confirmed as cleared, the infected person should not prepare food for others. Typhoid is treated with antibiotics such as azithromycin, fluoroquinolones, or third-generation cephalosporins. Resistance to these antibiotics has been developing, which has made treatment more difficult.

In 2015, 12.5 million new typhoid cases were reported. The disease is most common in India. Children are most commonly affected. Typhoid decreased in the developed world in the 1940s as a result of improved sanitation and the use of antibiotics. Every year about 400 cases are reported in the U.S. and an estimated 6,000 people have typhoid. In 2015, it resulted in about 149,000 deaths worldwide – down from 181,000 in 1990. Without treatment, the risk of death may be as high as 20%. With treatment, it is between 1% and 4%.

Typhus is a different disease. Owing to their similar symptoms, they were not recognized as distinct diseases until the 1800s. "Typhoid" means "resembling typhus".

Signs and symptoms

Classically, the progression of untreated typhoid fever has three distinct stages, each lasting about a week. Over the course of these stages, the patient becomes exhausted and emaciated.

- In the first week, the body temperature rises slowly, and fever fluctuations are seen with relative bradycardia (Faget sign), malaise, headache, and cough. A bloody nose (epistaxis) is seen in a quarter of cases, and abdominal pain is also possible. A decrease in the number of circulating white blood cells (leukopenia) occurs with eosinopenia and relative lymphocytosis; blood cultures are positive for S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhi. The Widal test is usually negative.

- In the second week, the person is often too tired to get up, with high fever in plateau around 40 °C (104 °F) and bradycardia (sphygmothermic dissociation or Faget sign), classically with a dicrotic pulse wave. Delirium can occur, where the patient is often calm, but sometimes becomes agitated. This delirium has given typhoid the nickname "nervous fever". Rose spots appear on the lower chest and abdomen in around a third of patients. Rhonchi (rattling breathing sounds) are heard in the base of the lungs. The abdomen is distended and painful in the right lower quadrant, where a rumbling sound can be heard. Diarrhea can occur in this stage, but constipation is also common. The spleen and liver are enlarged (hepatosplenomegaly) and tender, and liver transaminases are elevated. The Widal test is strongly positive, with antiO and antiH antibodies. Blood cultures are sometimes still positive.

- In the third week of typhoid fever, a number of complications can occur:

- The fever is still very high and oscillates very little over 24 hours. Dehydration ensues along with malnutrition, and the patient is delirious. A third of affected people develop a macular rash on the trunk.

- Intestinal haemorrhage due to bleeding in congested Peyer's patches occurs; this can be very serious, but is usually not fatal.

- Intestinal perforation in the distal ileum is a very serious complication and often fatal. It may occur without alarming symptoms until septicaemia or diffuse peritonitis sets in.

- Respiratory diseases such as pneumonia and acute bronchitis

- Encephalitis

- Neuropsychiatric symptoms (described as "muttering delirium" or "coma vigil"), with picking at bedclothes or imaginary objects.

- Metastatic abscesses, cholecystitis, endocarditis, and osteitis.

- Low platelet count (thrombocytopenia) is sometimes seen.

Causes

Bacteria

The Gram-negative bacterium that causes typhoid fever is Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhi. Based on MLST subtyping scheme, the two main sequence types of the S. Typhi are ST1 and ST2, which are widespread globally. Global phylogeographical analysis showed dominance of a haplotype 58 (H58), which probably originated in India during the late 1980s and is now spreading through the world with multi-drug resistance. A more detailed genotyping scheme was reported in 2016 and is now being used widely. This scheme reclassified the nomenclature of H58 to genotype 4.3.1.

Transmission

Unlike other strains of Salmonella, no animal carriers of typhoid are known. Humans are the only known carriers of the bacterium. S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhi is spread by the fecal-oral route from people who are infected and from asymptomatic carriers of the bacterium. An asymptomatic human carrier is someone who is still excreting typhoid bacteria in stool a year after the acute stage of the infection.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made by any blood, bone marrow, or stool cultures and with the Widal test (demonstration of antibodies against Salmonella antigens O-somatic and H-flagellar). In epidemics and less wealthy countries, after excluding malaria, dysentery, or pneumonia, a therapeutic trial time with chloramphenicol is generally undertaken while awaiting the results of the Widal test and blood and stool cultures.

Widal test

The Widal test is used to identify specific antibodies in the serum of people with typhoid by using antigen-antibody interactions.

In this test, the serum is mixed with a dead bacterial suspension of salmonella with specific antigens. If the patient's serum contains antibodies against those antigens, they get attached to them, forming clumps. If clumping does not occur, the test is negative. The Widal test is time-consuming and prone to significant false positives. It may also be falsely negative in recently infected people. But unlike the Typhidot test, the Widal test quantifies the specimen with titres.

Rapid diagnostic tests

Rapid diagnostic tests such as Tubex, Typhidot, and Test-It have shown moderate diagnostic accuracy.

Typhidot

Typhidot is based on the presence of specific IgM and IgG antibodies to a specific 50Kd OMP antigen. This test is carried out on a cellulose nitrate membrane where a specific S. typhi outer membrane protein is attached as fixed test lines. It separately identifies IgM and IgG antibodies. IgM shows recent infection; IgG signifies remote infection.

The sample pad of this kit contains colloidal gold-anti-human IgG or gold-anti-human IgM. If the sample contains IgG and IgM antibodies against those antigens, they will react and turn red. The typhidot test becomes positive within 2–3 days of infection.

Two colored bands indicate a positive test. A single control band indicates a negative test. A single first fixed line or no band at all indicates an invalid test. Typhidot's biggest limitation is that it is not quantitative, just positive or negative.

Tubex test

The Tubex test contains two types of particles: brown magnetic particles coated with antigen and blue indicator particles coated with O9 antibody. During the test, if antibodies are present in the serum, they will attach to the brown magnetic particles and settle at the base, while the blue indicator particles remain in the solution, producing a blue color, which means the test is positive.

If the serum does not have an antibody in it, the blue particles attach to the brown particles and settle at the bottom, producing a colorless solution, which means the test is negative.

Prevention

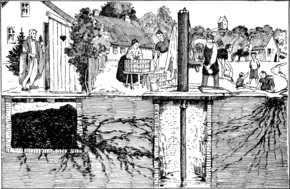

Sanitation and hygiene are important to prevent typhoid. It can spread only in environments where human feces can come into contact with food or drinking water. Careful food preparation and washing of hands are crucial to prevent typhoid. Industrialization contributed greatly to the elimination of typhoid fever, as it eliminated the public-health hazards associated with having horse manure in public streets, which led to a large number of flies, which are vectors of many pathogens, including Salmonella spp. According to statistics from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the chlorination of drinking water has led to dramatic decreases in the transmission of typhoid fever.

Vaccination

Two typhoid vaccines are licensed for use for the prevention of typhoid: the live, oral Ty21a vaccine (sold as Vivotif by Crucell Switzerland AG) and the injectable typhoid polysaccharide vaccine (sold as Typhim Vi by Sanofi Pasteur and Typherix by GlaxoSmithKline). Both are efficacious and recommended for travelers to areas where typhoid is endemic. Boosters are recommended every five years for the oral vaccine and every two years for the injectable form. An older, killed whole-cell vaccine is still used in countries where the newer preparations are not available, but this vaccine is no longer recommended for use because it has more side effects (mainly pain and inflammation at the site of the injection).

To help decrease rates of typhoid fever in developing nations, the World Health Organization (WHO) endorsed the use of a vaccination program starting in 1999. Vaccination has proven effective at controlling outbreaks in high-incidence areas and is also very cost-effective: prices are normally less than US$1 per dose. Because the price is low, poverty-stricken communities are more willing to take advantage of the vaccinations. Although vaccination programs for typhoid have proven effective, they alone cannot eliminate typhoid fever. Combining vaccines with public-health efforts is the only proven way to control this disease.

Since the 1990s, the WHO has recommended two typhoid fever vaccines. The ViPS vaccine is given by injection, and the Ty21a by capsules. Only people over age two are recommended to be vaccinated with the ViPS vaccine, and it requires a revaccination after 2–3 years, with a 55%–72% efficacy. The Ty21a vaccine is recommended for people five and older, lasting 5–7 years with 51%–67% efficacy. The two vaccines have proved safe and effective for epidemic disease control in multiple regions.

A version of the vaccine combined with a hepatitis A vaccine is also available.

Results of a phase 3 trial of typhoid conjugate vaccine (TCV) in December 2019 reported 81% fewer cases among children.

Treatment

Oral rehydration therapy

The rediscovery of oral rehydration therapy in the 1960s provided a simple way to prevent many of the deaths of diarrheal diseases in general.

Antibiotics

Where resistance is uncommon, the treatment of choice is a fluoroquinolone such as ciprofloxacin. Otherwise, a third-generation cephalosporin such as ceftriaxone or cefotaxime is the first choice. Cefixime is a suitable oral alternative.

Properly treated, typhoid fever is not fatal in most cases. Antibiotics such as ampicillin, chloramphenicol, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, amoxicillin, and ciprofloxacin have been commonly used to treat it. Treatment with antibiotics reduces the case-fatality rate to about 1%.

Without treatment, some patients develop sustained fever, bradycardia, hepatosplenomegaly, abdominal symptoms, and occasionally pneumonia. In white-skinned patients, pink spots, which fade on pressure, appear on the skin of the trunk in up to 20% of cases. In the third week, untreated cases may develop gastrointestinal and cerebral complications, which may prove fatal in 10%–20% of cases. The highest case fatality rates are reported in children under 4. Around 2%–5% of those who contract typhoid fever become chronic carriers, as bacteria persist in the biliary tract after symptoms have resolved.

Surgery

Surgery is usually indicated if intestinal perforation occurs. One study found a 30-day mortality rate of 9% (8/88), and surgical site infections at 67% (59/88), with the disease burden borne predominantly by low-resource countries.

For surgical treatment, most surgeons prefer simple closure of the perforation with drainage of the peritoneum. Small-bowel resection is indicated for patients with multiple perforations. If antibiotic treatment fails to eradicate the hepatobiliary carriage, the gallbladder should be resected. Cholecystectomy is sometimes successful, especially in patients with gallstones, but is not always successful in eradicating the carrier state because of persisting hepatic infection.

Resistance

As resistance to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and streptomycin is now common, these agents are no longer used as first–line treatment of typhoid fever. Typhoid resistant to these agents is known as multidrug-resistant typhoid.

Ciprofloxacin resistance is an increasing problem, especially in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. Many centres are shifting from ciprofloxacin to ceftriaxone as the first line for treating suspected typhoid originating in South America, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Thailand, or Vietnam. Also, it has been suggested that azithromycin is better at treating resistant typhoid than both fluoroquinolone drugs and ceftriaxone. Azithromycin can be taken by mouth and is less expensive than ceftriaxone, which is given by injection.

A separate problem exists with laboratory testing for reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin; current recommendations are that isolates should be tested simultaneously against ciprofloxacin (CIP) and against nalidixic acid (NAL), that isolates sensitive to both CIP and NAL should be reported as "sensitive to ciprofloxacin", and that isolates sensitive to CIP but not to NAL should be reported as "reduced sensitivity to ciprofloxacin". But an analysis of 271 isolates found that around 18% of isolates with a reduced susceptibility to fluoroquinolones, the class which CIP belongs (MIC 0.125–1.0 mg/L), would not be detected by this method.

Epidemiology

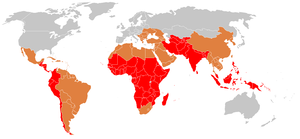

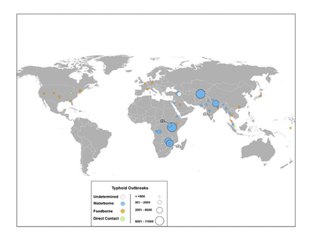

In 2000, typhoid fever caused an estimated 21.7 million illnesses and 217,000 deaths. It occurs most often in children and young adults between 5 and 19 years old. In 2013, it resulted in about 161,000 deaths – down from 181,000 in 1990. Infants, children, and adolescents in south-central and Southeast Asia have the highest rates of typhoid. Outbreaks are also often reported in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia. In 2000, more than 90% of morbidity and mortality due to typhoid fever occurred in Asia. In the U.S., about 400 cases occur each year, 75% of which are acquired while traveling internationally.

Before the antibiotic era, the case fatality rate of typhoid fever was 10%–20%. Today, with prompt treatment, it is less than 1%, but 3%–5% of people who are infected develop a chronic infection in the gall bladder. Since S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhi is human-restricted, these chronic carriers become the crucial reservoir, which can persist for decades for further spread of the disease, further complicating its identification and treatment. Lately, the study of S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhi associated with a large outbreak and a carrier at the genome level provides new insight into the pathogenesis of the pathogen.

In industrialized nations, water sanitation and food handling improvements have reduced the number of typhoid cases. Developing nations have the highest rates. These areas lack access to clean water, proper sanitation systems, and proper health-care facilities. In these areas, such access to basic public-health needs is not expected in the near future.

In 2004–2005 an outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo resulted in more than 42,000 cases and 214 deaths. Since November 2016, Pakistan has had an outbreak of extensively drug-resistant (XDR) typhoid fever.

In Europe, a report based on data for 2017 retrieved from The European Surveillance System (TESSy) on the distribution of confirmed typhoid and paratyphoid fever cases found that 22 EU/EEA countries reported a total of 1,098 cases, 90.9% of which were travel-related, mainly acquired during travel to South Asia.

Outbreaks

- Plague of Athens (suspected)

- "Burning Fever" outbreak among indigenous Americans. Between 1607 and 1624, 85% of the population at the James River died from a typhoid epidemic. The World Health Organization estimates the death toll was over 6,000 during this time.

- Maidstone, Kent outbreak in 1897–1898: 1,847 patients were recorded to have typhoid fever. This outbreak is notable because it was the first time a typhoid vaccine was deployed during a civilian outbreak. Almoth Edward Wright's vaccine was offered to 200 healthcare providers, and of the 84 individuals who received the vaccine none developed typhoid whereas 4 who had not been vaccinated became ill.

- American army in the Spanish-American war: government records estimate over 21,000 troops had typhoid, resulting in 2,200 deaths.

- In 1902, guests at mayoral banquets in Southampton and Winchester, England, became ill and four died, including the Dean of Winchester, after consuming oysters. The infection was due to oysters sourced from Emsworth, where the oyster beds had been contaminated with raw sewage.

- Jamaica Plain neighborhood, Boston in 1908 - linked to milk delivery. See history section, "carriers" for further details.

- Outbreak in upperclass New Yorkers who employed Mary Mallon - 51 cases and 3 deaths from 1907 to 1915.

- Aberdeen, Scotland, in summer 1964 - traced back to contaminated canned beef sourced from Argentina sold in markets. More than 500 patients were quarantined in the hospital for a minimum of four weeks, and the outbreak was contained without any deaths.

- Dushanbe, Tajikistan, in 1996–1997: 10,677 cases reported, 108 deaths

- Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, in 2004: 43,000 cases and over 200 deaths. A prospective study of specimens collected in the same region between 2007 and 2011 revealed about one third of samples obtained from patient samples were resistant to multiple antibiotics.

- Kampala, Uganda in 2015: 10,230 cases reported

History

Early descriptions

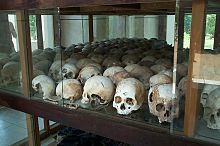

The plague of Athens, during the Peloponnesian War, was most likely an outbreak of typhoid fever. During the war, Athenians retreated into a walled-in city to escape attack from the Spartans. This massive influx of humans into a concentrated space overwhelmed the water supply and waste infrastructure, likely leading to unsanitary conditions as fresh water became harder to obtain and waste became more difficult to collect and remove beyond the city walls. In 2006, examining the remains for a mass burial site from Athens from around the time of the plague (~430 B.C.) revealed that fragments of DNA similar to modern day S. Typhi DNA were detected, whereas Yersinia pestis (plague), Rickettsia prowazekii (typhus), Mycobacterium tuberculosis, cowpox virus, and Bartonella henselae were not detected in any of the remains tested.

It is possible that the Roman emperor Augustus Caesar had either a liver abscess or typhoid fever, and survived by using ice baths and cold compresses as a means of treatment for his fever. There is a statue of the Greek physician, Antonius Musa, who treated his fever.

Definition and evidence of transmission

The French doctors Pierre-Fidele Bretonneau and Pierre-Charles-Alexandre Louis are credited with describing typhoid fever as a specific disease, unique from typhus. Both doctors performed autopsies on individuals who died in Paris due to fever – and indicated that many had lesions on the Peyer's patches which correlated with distinct symptoms before death. British medics were skeptical of the differentiation between typhoid and typhus because both were endemic to Britain at that time. However, in France only typhoid was present circulating in the population. Pierre-Charlles-Alexandre Louis also performed case studies and statistical analysis to demonstrate that typhoid was contagious - and that persons who already had the disease seemed to be protected. Afterward, several American doctors confirmed these findings, and then Sir William Jenner convinced any remaining skeptics that typhoid is a specific disease recognizable by lesions in the Peyer's patches by examining sixty-six autopsies from fever patients and concluding that the symptoms of headaches, diarrhea, rash spots, and abdominal pain were present only in patients who were found to have intestinal lesions after death; these observations solidified the association of the disease with the intestinal tract and gave the first clue to the route of transmission.

In 1847 William Budd learned of an epidemic of typhoid fever in Clifton, and identified that all 13 of 34 residents who had contracted the disease drew their drinking water from the same well. Notably, this observation was two years prior to John Snow discovering the route of contaminated water as the cause for a cholera outbreak. Budd later became health officer of Bristol and ensured a clean water supply, and documented further evidence of typhoid as a water-borne illness throughout his career.

Cause

Polish scientist Tadeusz Browicz described a short bacillus in the organs and feces of typhoid victims in 1874. Browicz was able to isolate and grow the bacilli but did not go as far as to insinuate or prove that they caused the disease.

In April 1880, three months prior to Eberth's publication, Edwin Klebs described short and filamentous bacilli in the Peyer's patches in typhoid victims. The bacterium's role in disease was speculated but not confirmed.

In 1880, Karl Joseph Eberth described a bacillus that he suspected was the cause of typhoid. Eberth is given credit for discovering the bacterium definitively by successfully isolating the same bacterium from 18 of 40 typhoid victims and failing to discover the bacterium present in any "control" victims of other diseases. In 1884, pathologist Georg Theodor August Gaffky (1850–1918) confirmed Eberth's findings. Gaffky isolated the same bacterium as Eberth from the spleen of a typhoid victim, and was able to grow the bacterium on solid media. The organism was given names such as Eberth's bacillus, Eberthella Typhi, and Gaffky-Eberth bacillus. Today, the bacillus that causes typhoid fever goes by the scientific name Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi.

Chlorination of water

Most developed countries had declining rates of typhoid fever throughout the first half of the 20th century due to vaccinations and advances in public sanitation and hygiene. In 1893 attempts were made to chlorinate the water supply in Hamburg, Germany and in 1897 Maidstone, England, was the first town to have its entire water supply chlorinated. In 1905, following an outbreak of typhoid fever, the City of Lincoln, England, instituted permanent water chlorination. The first permanent disinfection of drinking water in the US was made in 1908 to the Jersey City, New Jersey, water supply. Credit for the decision to build the chlorination system has been given to John L. Leal. The chlorination facility was designed by George W. Fuller.

Outbreaks in traveling military groups led to the creation of the Lyster bag in 1915; a bag with a faucet which can be hung from a tree or pole, filled with water, and comes with a chlorination tablet to drop into the water. The Lyster bag was essential for the survival of American soldiers in the Vietnam War.

Direct transmission and carriers

There were several occurrences of milk delivery men spreading typhoid fever throughout the communities they served. Although typhoid is not spread through milk itself, there were several examples of milk distributors in many locations watering their milk down with contaminated water, or cleaning the glass bottles the milk was placed in with contaminated water. Boston had two such cases around the turn of the 20th century. In 1899 there were 24 cases of typhoid traced to a single milkman, whose wife had died of typhoid fever a week before the outbreak. In 1908, J.J. Fallon, who was also a milkman, died of typhoid fever. Following his death and confirmation of the typhoid fever diagnosis, the city conducted an investigation of typhoid symptoms and cases along his route and found evidence of a significant outbreak. A month after the outbreak was first reported, the Boston Globe published a short statement declaring the outbreak over, stating "[a]t Jamaica Plain there is a slight increase, the total being 272 cases. Throughout the city there is a total of 348 cases." There was at least one death reported during this outbreak: Mrs. Sophia S. Engstrom, aged 46. Typhoid continued to ravage the Jamaica Plain neighborhood in particular throughout 1908, and several more people were reported dead due to typhoid fever, although these cases were not explicitly linked to the outbreak. The Jamaica Plain neighborhood at that time was home to many working-class and poor immigrants, mostly from Ireland.

The most notorious carrier of typhoid fever, but by no means the most destructive, was Mary Mallon, known as Typhoid Mary. Although other cases of human-to-human spread of typhoid were known at the time, the concept of an asymptomatic carrier, who was able to transmit disease, had only been hypothesized and not yet identified or proven. Mary Mallon became the first known example of an asymptomatic carrier of an infectious disease, making typhoid fever the first known disease being transmissible through asymptomatic hosts. The cases and deaths caused by Mallon were mainly upper-class families in New York City. At the time of Mallon's tenure as a personal cook for upper-class families, New York City reported 3,000 to 4,500 cases of typhoid fever annually. In the summer of 1906 two daughters of a wealthy family and maids working in their home became ill with typhoid fever. After investigating their home water sources and ruling out water contamination, the family hired civil engineer George Soper to conduct an investigation of the possible source of typhoid fever in the home. Soper described himself as an "epidemic fighter". His investigation ruled out many sources of food, and led him to question if the cook the family hired just prior to their household outbreak, Mallon, was the source. Since she had already left and begun employment elsewhere, he proceeded to track her down in order to obtain a stool sample. When he was able to finally meet Mallon in person he described her by saying "Mary had a good figure and might have been called athletic had she not been a little too heavy." In recounts of Soper's pursuit of Mallon, his only remorse appears to be that he was not given enough credit for his relentless pursuit and publication of her personal identifying information, stating that the media "rob[s] me of whatever credit belongs to the discovery of the first typhoid fever carrier to be found in America." Ultimately, 51 cases and 3 deaths were suspected to be caused by Mallon.

In 1924 the city of Portland, Oregon, experienced an outbreak of typhoid fever, consisting of 26 cases and 5 deaths, all deaths due to intestinal hemorrhage. All cases were concluded to be due to a single milk farm worker, who was shedding large amounts of the typhoid pathogen in his urine. Misidentification of the disease, due to inaccurate Widal test results, delayed identification of the carrier and proper treatment. Ultimately, it took four samplings of different secretions from all of the dairy workers in order to successfully identify the carrier. Upon discovery, the dairy worker was forcibly quarantined for seven weeks, and regular samples were taken, most of the time the stool samples yielding no typhoid and often the urine yielding the pathogen. The carrier was reported as being 72 years old and appearing in excellent health with no symptoms. Pharmaceutical treatment decreased the amount of bacteria secreted, however, the infection was never fully cleared from the urine, and the carrier was released "under orders never again to engage in the handling of foods for human consumption." At the time of release, the authors noted "for more than fifty years he has earned his living chiefly by milking cows and knows little of other forms of labor, it must be expected that the closest surveillance will be necessary to make certain that he does not again engage in this occupation."

Overall, in the early 20th century the medical profession began to identify carriers of the disease, and evidence of transmission independent of water contamination. In a 1933 American Medical Association publication, physicians' treatment of asymptomatic carriers is best summarized by the opening line "Carriers of typhoid bacilli are a menace". Within the same publication, the first official estimate of typhoid carriers is given: 2 to 5% of all typhoid patients, and distinguished between temporary carriers and chronic carriers. The authors further estimate that there are four to five chronic female carriers to every one male carrier, although offered no data to explain this assertion of a gender difference in the rate of typhoid carriers. As far as treatment, the authors suggest: "When recognized, carriers must be instructed as to the disposal of excreta as well as to the importance of personal cleanliness. They should be forbidden to handle food or drink intended for others, and their movements and whereabouts must be reported to the public health officers".

Today, typhoid carriers exist all over the world, but the highest incidence of asymptomatic infection is likely to occur in South/Southeast Asian and Sub-Saharan countries. The Los Angeles County department of public health tracks typhoid carriers and reports the number of carriers identified within the county yearly; between 2006 and 2016 0-4 new cases of typhoid carriers were identified per year. Cases of typhoid fever must be reported within one working day from identification. As of 2018, chronic typhoid carriers must sign a "Carrier Agreement" and are required to test for typhoid shedding twice yearly, ideally every 6 months. Carriers may be released from their agreements upon fulfilling "release" requirements, based on completion of a personalized treatment plan designed with medical professionals. Fecal or gallbladder carrier release requirements: 6 consecutive negative feces and urine specimens submitted at 1-month or greater intervals beginning at least 7 days after completion of therapy. Urinary or kidney carrier release requirements: 6 consecutive negative urine specimens submitted at 1-month or greater intervals beginning at least 7 days after completion of therapy. As of 2016 the male:female ratio of carriers in Los Angeles county was 3:1.

Due to the nature of asymptomatic cases, many questions remain about how individuals are able to tolerate infection for long periods of time, how to identify such cases, and efficient options for treatment. Researchers are currently working to understand asymptomatic infection with Salmonella species by studying infections in laboratory animals, which will ultimately lead to improved prevention and treatment options for typhoid carriers. In 2002, John Gunn described the ability of Salmonella sp. to form biofilms on gallstones in mice, providing a model for studying carriage in the gallbladder. Denise Monack and Stanley Falkow described a mouse model of asymptomatic intestinal and systemic infection in 2004, and Monack went on to demonstrate that a sub-population of superspreaders are responsible for the majority of transmission to new hosts, following the 80/20 rule of disease transmission, and that the intestinal microbiota likely plays a role in transmission. Monack's mouse model allows long-term carriage of salmonella in mesenteric lymph nodes, spleen and liver.

Vaccine development

British bacteriologist Almroth Edward Wright first developed an effective typhoid vaccine at the Army Medical School in Netley, Hampshire. It was introduced in 1896 and used successfully by the British during the Second Boer War in South Africa. At that time, typhoid often killed more soldiers at war than were lost due to enemy combat. Wright further developed his vaccine at a newly opened research department at St Mary's Hospital Medical School in London from 1902, where he established a method for measuring protective substances (opsonin) in human blood. Wright's version of the typhoid vaccine was produced by growing the bacterium at body temperature in broth, then heating the bacteria to 60 °C to "heat inactivate" the pathogen, killing it, while keeping the surface antigens intact. The heat-killed bacteria was then injected into a patient. To show evidence of the vaccine's efficacy, Wright then collected serum samples from patients several weeks post-vaccination, and tested their serum's ability to agglutinate live typhoid bacteria. A "positive" result was represented by clumping of bacteria, indicating that the body was producing anti-serum (now called antibodies) against the pathogen.

Citing the example of the Second Boer War, during which many soldiers died from easily preventable diseases, Wright convinced the British Army that 10 million vaccine doses should be produced for the troops being sent to the Western Front, thereby saving up to half a million lives during World War I. The British Army was the only combatant at the outbreak of the war to have its troops fully immunized against the bacterium. For the first time, their casualties due to combat exceeded those from disease.

In 1909, Frederick F. Russell, a U.S. Army physician, adopted Wright's typhoid vaccine for use with the Army, and two years later, his vaccination program became the first in which an entire army was immunized. It eliminated typhoid as a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the U.S. military. Typhoid vaccination for members of the American military became mandatory in 1911. Before the vaccine, the rate of typhoid fever in the military was 14,000 or greater per 100,000 soldiers. By World War I, the rate of typhoid in American soldiers was 37 per 100,000.

During the second world war, the United States army authorized the use of a trivalent vaccine – containing heat-inactivated Typhoid, Paratyphi A and Paratyphi B pathogens.

In 1934, discovery of the Vi capsular antigen by Arthur Felix and Miss S. R. Margaret Pitt enabled development of the safer Vi Antigen vaccine – which is widely in use today. Arthur Felix and Margaret Pitt also isolated the strain Ty2, which became the parent strain of Ty21a, the strain used as a live-attenuated vaccine for typhoid fever today.

Antibiotics and resistance

Chloramphenicol was isolated from Streptomyces by David Gotlieb during the 1940s. In 1948 American army doctors tested its efficacy in treating typhoid patients in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Individuals who received a full course of treatment cleared the infection, whereas patients given a lower dose had a relapse. Asymptomatic carriers continued to shed bacilli despite chloramphenicol treatment - only ill patients were improved with chloramphenicol. Resistance to chloramphenicol became frequent in Southeast Asia by the 1950s, and today chloramphenicol is only used as a last resort due to the high prevalence of resistance.

Terminology

The disease has been referred to by various names, often associated with symptoms, such as gastric fever, enteric fever, abdominal typhus, infantile remittant fever, slow fever, nervous fever, pythogenic fever, drain fever and low fever.