Circumnavigation is the complete navigation around an entire island, continent, or astronomical body (e.g. a planet or moon). This article focuses on the circumnavigation of Earth.

The first circumnavigation of the Earth was the Magellan Expedition, which sailed from Sanlucar de Barrameda, Spain in 1519 and returned in 1522, after crossing the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian oceans. Since the rise of commercial aviation in the late 20th century, circumnavigating Earth is straightforward, usually taking days instead of years. Today, the challenge of circumnavigating Earth has shifted towards human and technological endurance, speed, and less conventional methods.

Etymology

The word circumnavigation is a noun formed from the verb circumnavigate, from the past participle of the Latin verb circumnavigare, from circum "around" + navigare "to sail" (see further Navigation § Etymology).

Definition

A person walking completely around either pole will cross all meridians, but this is not generally considered a "circumnavigation". The path of a true (global) circumnavigation forms a continuous loop on the surface of Earth separating two regions of comparable area. A basic definition of a global circumnavigation would be a route which covers roughly a great circle, and in particular one which passes through at least one pair of points antipodal to each other. In practice, people use different definitions of world circumnavigation to accommodate practical constraints, depending on the method of travel. Since the planet is quasispheroidal, a trip from one Pole to the other, and back again on the other side, would technically be a circumnavigation. There are practical difficulties (namely, the Arctic ice pack and the Antarctic ice sheet) in such a voyage, although it was successfully undertaken in the early 1980s by Ranulph Fiennes.

History

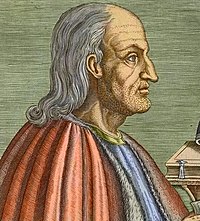

The first circumnavigation was that of the ship Victoria between 1519 and 1522, now known as the Magellan–Elcano expedition. It was a Castilian (Spanish) voyage of discovery. The voyage started in Seville, crossed the Atlantic Ocean, and—after several stops—rounded the southern tip of South America, where the expedition named the Strait of Magellan. It then continued across the Pacific, discovering a number of islands on its way (including Guam), before arriving in the Philippines. The voyage was initially led by the Portuguese Ferdinand Magellan but he was killed on Mactan in the Philippines in 1521. The remaining sailors decided to circumnavigate the world instead of making the return voyage—no passage east across the Pacific would be successful for four decades—and continued the voyage across the Indian Ocean, round the southern cape of Africa, north along Africa's Atlantic coasts, and back to Spain in 1522. Only 18 men were still with the expedition at the end, including its surviving captain, the Spaniard Juan Sebastián Elcano.

The next to circumnavigate the globe were the survivors of the Castilian/Spanish expedition of García Jofre de Loaísa between 1525 and 1536. None of the seven original ships of the Loaísa expedition nor its first four leaders—Loaísa, Elcano, Salazar, and Íñiguez—survived to complete the voyage. The last of the original ships, the Santa María de la Victoria, was sunk in 1526 in the East Indies (now Indonesia) by the Portuguese. Unable to press forward or retreat, Hernando de la Torre erected a fort on Tidore, received reinforcements under Alvaro de Saavedra that were similarly defeated, and finally surrendered to the Portuguese. In this way, a handful of survivors became the second group of circumnavigators when they were transported under guard to Lisbon in 1536. A third group came from the 117 survivors of the similarly failed Villalobos Expedition in the next decade; similarly ruined and starved, they were imprisoned by the Portuguese and transported back to Lisbon in 1546.

In 1577, Elizabeth I sent Francis Drake to start an expedition against the Spanish along the Pacific coast of the Americas. Drake set out from Plymouth, England in November 1577, aboard Pelican, which he renamed Golden Hind mid-voyage. In September 1578, the ship passed south of Tierra del Fuego, the southern tip of South America, through the area now known as the Drake Passage. In June 1579, Drake landed somewhere north of Spain's northernmost claim in Alta California, presumably Drakes Bay. Drake completed the second complete circumnavigation of the world in a single vessel on September 1580, becoming the first commander to survive the entire circumnavigation.

Thomas Cavendish completed his circumnavigation between 1586 and 1588 in record time—in two years and 49 days, nine months faster than Drake. It was also the first deliberately planned voyage of the globe.

For the wealthy, long voyages around the world, such as was done by Ulysses S. Grant, became possible in the 19th century, and the two World Wars moved vast numbers of troops around the planet. However, it was the rise of commercial aviation in the late 20th century that made circumnavigation, when compared to the Magellan–Elcano expedition, quicker and safer.

Nautical

The nautical global and fastest circumnavigation record is currently held by a wind-powered vessel, the trimaran IDEC 3. The record was established by six sailors: Francis Joyon, Alex Pella, Clément Surtel, Gwénolé Gahinet, Sébastien Audigane and Bernard Stamm; who wrote themselves into history books on 26 January 2017, by circumnavigating the globe in 40 days, 23 hours, 30 minutes and 30 seconds. The absolute speed sailing record around the world followed the North Atlantic Ocean, Equator, South Atlantic Ocean, Southern Ocean, South Atlantic Ocean, Equator, North Atlantic Ocean route in an easterly direction.

Wind powered

The map on the right shows, in red, a typical, non-competitive, route for a sailing circumnavigation of the world by the trade winds and the Suez and Panama canals; overlaid in yellow are the points antipodal to all points on the route. It can be seen that the route roughly approximates a great circle, and passes through two pairs of antipodal points. This is a route followed by many cruising sailors, going in the western direction; the use of the trade winds makes it a relatively easy sail, although it passes through a number of zones of calms or light winds.

In yacht racing, a round-the-world route approximating a great circle would be quite impractical, particularly in a non-stop race where use of the Panama and Suez Canals would be impossible. Yacht racing therefore defines a world circumnavigation to be a passage of at least 21,600 nautical miles (40,000 km) in length which crosses the equator, crosses every meridian and finishes in the same port as it starts. The second map on the right shows the route of the Vendée Globe round-the-world race in red; overlaid in yellow are the points antipodal to all points on the route. It can be seen that the route does not pass through any pairs of antipodal points. Since the winds in the higher southern latitudes predominantly blow west-to-east it can be seen that there are an easier route (west-to-east) and a harder route (east-to-west) when circumnavigating by sail; this difficulty is magnified for square-rig vessels due to the square rig's dramatic lack of upwind ability when compared to a more modern Bermuda rig.

For around the world sailing records, there is a rule saying that the length must be at least 21,600 nautical miles calculated along the shortest possible track from the starting port and back that does not cross land and does not go below 63°S. It is allowed to have one single waypoint to lengthen the calculated track. The equator must be crossed.

The solo wind powered circumnavigation record of 42 days, 16 hours, 40 minutes and 35 seconds was established by François Gabart on the maxi-multihull sailing yacht MACIF and completed on 7 December 2017. The voyage followed the North Atlantic Ocean, Equator, South Atlantic Ocean, Southern Ocean, South Atlantic Ocean, Equator, North Atlantic Ocean route in an easterly direction.

Mechanically powered

Since the advent of world cruises in 1922, by Cunard's Laconia, thousands of people have completed circumnavigations of the globe at a more leisurely pace. Typically, these voyages begin in New York City or Southampton, and proceed westward. Routes vary, either travelling through the Caribbean and then into the Pacific Ocean via the Panama Canal, or around Cape Horn. From there ships usually make their way to Hawaii, the islands of the South Pacific, Australia, New Zealand, then northward to Hong Kong, South East Asia, and India. At that point, again, routes may vary: one way is through the Suez Canal and into the Mediterranean; the other is around Cape of Good Hope and then up the west coast of Africa. These cruises end in the port where they began.

In 1960, the American nuclear-powered submarine USS Triton circumnavigated the globe in 60 days, 21 hours for Operation Sandblast.

The current circumnavigation record in a powered boat of 60 days 23 hours and 49 minutes was established by a voyage of the wave-piercing trimaran Earthrace which was completed on 27 June 2008. The voyage followed the North Atlantic Ocean, Panama Canal, Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean, Suez Canal, Mediterranean Sea route in a westerly direction.

Aviation

In 1922 Norman Macmillan (RAF officer), Major W T Blake and Geoffrey Malins made an unsuccessful attempt to fly a Daily News-sponsored round-the-world flight. The first aerial circumnavigation of the planet was flown in 1924 by aviators of the U.S. Army Air Service in a quartet of Douglas World Cruiser biplanes. The first non-stop aerial circumnavigation of the planet was flown in 1949 by Lucky Lady II, a United States Air Force Boeing B-50 Superfortress.

Since the development of commercial aviation, there are regular routes that circle the globe, such as Pan American Flight One (and later United Airlines Flight One). Today planning such a trip through commercial flight connections is simple.

The first lighter-than-air aircraft of any type to circumnavigate under its own power was the rigid airship LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin, which did so in 1929.

Aviation records take account of the wind circulation patterns of the world; in particular the jet streams, which circulate in the northern and southern hemispheres without crossing the equator. There is therefore no requirement to cross the equator, or to pass through two antipodal points, in the course of setting a round-the-world aviation record. Thus, for example, Steve Fossett's global circumnavigation by balloon was entirely contained within the southern hemisphere.

For powered aviation, the course of a round-the-world record must start and finish at the same point and cross all meridians; the course must be at least 36,770 kilometres (19,850 nmi) long (which is approximately the length of the Tropic of Cancer). The course must include set control points at latitudes outside the Arctic and Antarctic circles.

In ballooning, which is at the mercy of the winds, the requirements are even more relaxed. The course must cross all meridians, and must include a set of checkpoints which are all outside of two circles, chosen by the pilot, having radii of 3,335.85 kilometres (2,072.80 mi) and enclosing the poles (though not necessarily centred on them).

Astronautics

The first person to fly in space, Yuri Gagarin, also became the first person to complete an orbital spaceflight in the Vostok 1 spaceship within 2 hours in 1961.

Flight started at 63° E and ended 45° E longitude; thus Gagarin did not circumnavigate Earth completely.

Gherman Titov in the Vostok 2 was the first human to circumnavigate Earth in spaceflight and made 17.5 orbits.

Human-powered

According to adjudicating bodies Guinness World Records and Explorersweb, Jason Lewis completed the first human-powered circumnavigation of the globe on 6 October 2007. This was part of a thirteen-year journey entitled Expedition 360.

In 2012, Turkish-born American adventurer Erden Eruç completed the first entirely solo human-powered circumnavigation, travelling by rowboat, sea kayak, foot and bicycle from 10 July 2007 to 21 July 2012, crossing the equator twice, passing over 12 antipodal points, and logging 66,299 kilometres (41,196 mi) in 1,026 days of travel time, excluding breaks.

National Geographic lists Colin Angus as being the first to complete a global circumnavigation. However, his journey did not cross the equator or hit the minimum of two antipodal points as stipulated by the rules of Guinness World Records and AdventureStats by Explorersweb.

People have both bicycled and run around the world, but the oceans have had to be covered by air or sea travel, making the distance shorter than the Guinness guidelines. To go from North America to Asia on foot is theoretically possible but very difficult. It involves crossing the Bering Strait on the ice, and around 3,000 kilometres (1,900 mi) of roadless swamped or freezing cold areas in Alaska and eastern Russia. No one has so far travelled all of this route by foot. David Kunst was the first verified person to walk around the world between 20 June 1970 and 5 October 1974.

Maritime

- The Castilian ('Spanish') Magellan-Elcano expedition of August 1519 to 8 September 1522, started by Portuguese navigator Fernão de Magalhães (Ferdinand Magellan) and completed by Spanish Basque navigator Juan Sebastián Elcano after Magellan's death, was the first global circumnavigation (see Victoria).

- The survivors of García Jofre de Loaísa's Spanish expedition 1525–1536, including Andrés de Urdaneta and Hans von Aachen, who was also one of the 18 survivors of Magellan's expedition, making him the first to circumnavigate the world twice.

- Francis Drake carried out the second circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition (and on a single independent voyage), from 1577 to 1580.

- Jeanne Baret is the first woman to complete a voyage of circumnavigation, in 1766–1769.

- John Hunter commanded the first ship to circumnavigate the World starting from Australia, between 2 September 1788 and 8 May 1789, with one stop in Cape Town to load supplies for the colony of New South Wales.

- HMS Driver completed the first circumnavigation by a steam ship in 1845–1847.

- The Spanish frigate Numancia, commanded by Juan Bautista Antequera y Bobadilla, completed the first circumnavigation by an ironclad in 1865–1867.

- Joshua Slocum completed the first single-handed circumnavigation in 1895–1898.

- In 1960, the U.S. Navy nuclear-powered submarine USS Triton (SSRN-586) completed the submerged circumnavigation.

- In 1969, Robin Knox-Johnston became the first person to complete a single-handed non-stop circumnavigation.

- In 1999, Jesse Martin became the youngest recognized person to complete an unassisted, non-stop, circumnavigation, at the age of 18.

- In 2001, the U.S. Coast Guard USCGC Sherman (WHEC-720) became the first Coast Guard vessel to circumnavigate the globe.

- In 2012, PlanetSolar became the first ever solar electric vehicle to circumnavigate the globe.

- In 2012, Laura Dekker became the youngest person to circumnavigate the globe single-handed, with stops, at the age of 16.

- In 2017, trimaran IDEC 3 with sailors: Francis Joyon, Alex Pella, Clément Surtel, Gwénolé Gahinet, Sébastien Audigane and Bernard Stamm completes the fastest circumnavigation of the globe ever; in 40 days, 23 hours, 30 minutes and 30 seconds. The voyage followed the North Atlantic Ocean, Equator, South Atlantic Ocean, Southern Ocean, South Atlantic Ocean, Equator, North Atlantic Ocean route in an easterly direction.

- In 2022, the MV Astra, a former Swedish Sea Rescue Society ship became the first sub-24m motor-powered vessel to circumnavigate the globe via the southern capes.

Aviation

- United States Army Air Service, 1924, first aerial circumnavigation, 175 days, covering 44,360 kilometres (27,560 mi), with examples of the Douglas World Cruiser biplane.

- In 1949, the Lucky Lady II, a Boeing B-50 Superfortress of the U.S. Air Force, commanded by Captain James Gallagher, became the first aeroplane to circle the world non-stop (by refueling the plane in flight). Total time airborne was 94 hours and 1 minute.

- In 1957, three United States Air Force Boeing B-52 Stratofortresses made the first non-stop jet-aircraft circumnavigation in 45 hours and 19 minutes, with two in-air refuelings.

- In 1964, Geraldine "Jerrie" Mock was the first woman to fly solo around the world.

- In 1986, Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager made the first non-refueled circumnavigation in an airplane (Rutan Voyager), in 9 days, 3 minutes and 44 seconds.

- In 1999, Bertrand Piccard and Brian Jones, achieved the first non-stop balloon circumnavigation in Breitling Orbiter 3.

- In 2002, Steve Fossett, after flying on the Spirit of Freedom balloon gondola, became the first person to fly around the world alone, nonstop in any kind of aircraft. Fossett's sole source of aid was a control center in Brookings Hall of Washington University in St. Louis.

- In 2005, Steve Fossett, flying a Virgin Atlantic GlobalFlyer, set the current record for fastest aerial circumnavigation (first non-stop, non-refueled solo circumnavigation in an airplane) in 67 hours, covering 37,000 kilometers.

- In 2014, Matt Guthmiller became the youngest person to solo circumnavigate by air at age 19 years, 7 months, and 15 days.

- In 2016, Bertrand Piccard and André Borschberg completed the first solar-powered aircraft circumnavigation of the world in Solar Impulse 2.

- In 2020, One More Orbit completed the fastest circumnavigation via both geographic poles in a Gulfstream G650ER.

- In 2020, Robert DeLaurentis and his twin-engine aircraft "Citizen of the World" became the first pilot and plane to successfully use biofuels over the North and South poles.

Land

- In 1841–1842 Sir George Simpson made the first "land circumnavigation", crossing Canada and Siberia and returning to London.

- Ranulph Fiennes and Charlie Burton are credited with the first north–south circumnavigation of the Earth.

Human

- On 13 June 2003, Robert Garside completed the first recognized run around the world, taking 5+1⁄2 years; the run was authenticated in 2007 by Guinness World Records after five years of verification.

- On 6 October 2007, Jason Lewis completed the first human-powered circumnavigation of the globe (including human-powered sea crossings).

- On 21 July 2012, Erden Eruç completed the first entirely solo human-powered circumnavigation of the globe.