A mixed economy is variously defined as an economic system blending elements of a market economy with elements of a planned economy, markets with state interventionism, or private enterprise with public enterprise. Common to all mixed economies is a combination of free-market principles and principles of socialism. While there is no single definition of a mixed economy, one definition is about a mixture of markets with state interventionism, referring specifically to a capitalist market economy with strong regulatory oversight and extensive interventions into markets. Another is that of active collaboration of capitalist and socialist visions. Yet another definition is apolitical in nature, strictly referring to an economy containing a mixture of private enterprise with public enterprise. Alternatively, a mixed economy can refer to a reformist transitionary phase to a socialist economy that allows a substantial role for private enterprise and contracting within a dominant economic framework of public ownership. This can extend to a Soviet-type planned economy that has been reformed to incorporate a greater role for markets in the allocation of factors of production.

The idea behind a mixed economy, as advocated by John Maynard Keynes and several others, was not to abandon the capitalist mode of production but to retain a predominance of private ownership and control of the means of production, with profit-seeking enterprise and the accumulation of capital as its fundamental driving force. The difference from a laissez-faire capitalist system is that markets are subject to varying degrees of regulatory control and governments wield indirect macroeconomic influence through fiscal and monetary policies with a view to counteracting capitalism's history of boom and bust cycles, unemployment, and economic inequality. In this framework, varying degrees of public utilities and essential services are provided by the government, with state activity providing public goods and universal civic requirements, including education, healthcare, physical infrastructure, and management of public lands. This contrasts with laissez-faire capitalism, where state activity is limited to maintaining order and security, and providing public goods and services, as well as the legal framework for the protection of property rights and enforcement of contracts.

About Western European economic models as championed by conservatives (Christian democrats), liberals (social liberals), and socialists (social democrats - social democracy was created as a combination of socialism and liberal democracy) as part of the post-war consensus, a mixed economy is in practice a form of capitalism where most industries are privately owned but there is a number of utilities and essential services under public ownership, usually around 15 to 20 percent. In the post-war era, Western European social democracy became associated with this economic model. As an economic ideal, mixed economies are supported by people of various political persuasions, in particular social democrats. The contemporary capitalist welfare state has been described as a type of mixed economy in the sense of state interventionism, as opposed to a mixture of planning and markets, since economic planning was not a key feature or component of the welfare state.

Overview

While there is no single all-encompassing definition of a mixed economy, there are generally two major definitions, one being political and the other apolitical. The political definition of a mixed economy refers to the degree of state interventionism in a market economy, portraying the state as encroaching onto the market under the assumption that the market is the natural mechanism for allocating resources. The political definition is limited to capitalistic economies and precludes an extension to non-capitalist systems, and aims to measure the degree of state influence through public policies in the market.

The apolitical definition relates to patterns of ownership and management of economic enterprises in an economy, strictly referring to a mix of public and private ownership of enterprises in the economy and is unconcerned with political forms and public policy. Alternatively, it refers to a mixture of economic planning and markets for the allocation of resources.

History

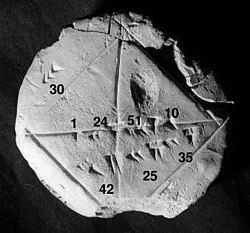

The term mixed economy arose in the context of political debate in the United Kingdom in the postwar period, although the set of policies later associated with the term had been advocated from at least the 1930s. The oldest documented mixed economies in the historical record are found as early as the 4th millennium BC in the Ancient Mesopotamian civilization in city-states such as Uruk and Ebla. The economies of the Ancient Greek city-states can also best be characterized as mixed economies. It is also possible that the Phoenician city-states depended on mixed economies to manage trade. Before being conquered by the Roman Republic, the Etruscan civilization engaged in a "strong mixed economy". In general, the cities of the Ancient Mediterranean in regions such as North Africa, Iberia, and Southern France, among others, all practiced some form of a mixed economy. According to the historians Michael Rostovtzeff and Pierre Lévêque, the economies of Ancient Egypt, pre-Columbian Mesoamerican, Ancient Peru, Ancient China, and the Roman Empire after Diocletian all had the basic characteristics of mixed economies. After the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire in its eastern part continued to have a mixed economy until its destruction by the Ottoman Empire.

Medieval Islamic societies drew their primary material basis from the classical Mediterranean mixed economies that preceded them, and the economies of Islamic empires such as the Abbasid Caliphate dealt with their emerging, prominent capitalistic sectors or market economies through regulation via state, social, or religious institutions. Due to having low, diffuse populations, and disconnected trade, the economies of Europe could not have supported centralized states or mixed economies and instead a primarily agrarian feudalism predominated for the centuries following the collapse of Rome. With the recovery of populations and the rise of medieval communes from the 11th century onward, economic and political power once again became centralized. According to Murray Bookchin, mixed economies, which had grown out of the medieval communes, were beginning to emerge in Europe by the 15th century as feudalism declined. In 17th-century France, Jean-Baptiste Colbert acting as finance minister for Louis XIV attempted to institute a mixed economy on a national scale.

The American System initially proposed by the first United States Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, and supported by later American leaders such as Henry Clay, John C Calhoun, and Daniel Webster, exhibited the traits of a mixed economy combining protectionism, laissez-faire, and infrastructure spending. After 1851, Napoleon III began the process of replacing the old agricultural economy of France with one that was mixed and focused on industrialization. By 1914 and the start of World War I, Germany had developed a mixed economy with government co-ownership of infrastructure and industry along with a comprehensive social welfare system. After the 1929 stock crash and subsequent Great Depression threw much of the global economy into a severe economic decline, British economists such as John Maynard Keynes began to advocate for economic theories that argued more government intervention in the economy. Harold Macmillan, a British politician in the Conservative Party, also began to advocate for a mixed economy in his books Reconstruction (1933) and The Middle Way (1938). Supporters of the mixed economy included R. H. Tawney, Anthony Crosland, and Andrew Shonfield, who were mostly associated with the Labour Party in the United Kingdom. During the post-war period and coinciding with the Golden Age of Capitalism, there was general worldwide rejection of laissez-faire economics as capitalist countries embraced mixed economies founded on economic planning, intervention, and welfare.

Political philosophy

In the apolitical sense, the term mixed economy is used to describe economic systems that combine various elements of market economies and planned economies. As most political-economic ideologies are defined in an idealized sense, what is described rarely—if ever—exists in practice. Most would not consider it unreasonable to label an economy that, while not being a perfect representation, very closely resembles an ideal by applying the rubric that denominates that ideal. When a system in question, diverges to a significant extent from an idealized economic model or ideology, the task of identifying it can become problematic, and the term mixed economy was coined. As it is unlikely that an economy will contain a perfectly even mix, mixed economies are usually noted as being skewed towards either private ownership or public ownership, toward capitalism or socialism, or a market economy or command economy in varying degrees.

Catholic social teaching

Jesuit author David Hollenbach has argued that Catholic social teaching calls for a "new form" of mixed economy. He refers back to Pope Pius XI's statement that government "should supply help to the members of the social body, but may never destroy or absorb them". Hollenbach writes that a socially just mixed economy involves labor, management, and the state working together through a pluralistic system that distributes economic power widely. Pope Francis has criticised neoliberalism throughout his papacy and encouraged state welfare programs for "the redistribution of wealth, looking out for the dignity of the poorest who risk always ending up crushed by the powerful". In Evangelii gaudium, he states: "Some people continue to defend trickle-down theories which assume that economic growth, encouraged by a free market, will inevitably succeed in bringing about greater justice and inclusiveness in the world. This opinion, which has never been confirmed by the facts, expresses a crude and naïve trust in the goodness of those wielding economic power and in the sacralized workings of the prevailing economic system. Meanwhile, the excluded are still waiting."

Catholic social teaching opposes both unregulated capitalism and state socialism. Subsequent scholars have noted that conceiving of subsidiarity as a "top-down, government-driven political exercise" requires a selective reading of 1960s encyclicals. A more comprehensive reading of Catholic social teaching suggests a conceptualization of subsidiarity as a "bottom-up concept" that is "rooted in recognition of a common humanity, not in the political equivalent of noblese oblige".

Fascism

Although fascism is primarily a political ideology that stresses the importance of cultural and social issues over economics, it is generally supportive of a broadly capitalistic mixed economy. It supports state interventionism into markets and private enterprise, alongside a fascist corporatist framework, referred to as a third position that ostensibly aims to be a middle-ground between socialism and capitalism by mediating labor and business disputes to promote national unity. 20th-century fascist regimes in Italy and Germany adopted large public works programs to stimulate their economies and state interventionism in largely private sector-dominated economies to promote re-armament and national interests. During World War II, Germany implemented a war economy that combined a free market with central planning. The Nazi government collaborated with leading German business interests, who supported the war effort in exchange for advantageous contracts, subsidies, the suppression of trade unions, and the allowance of cartels and monopolies. Scholars have drawn parallels between the American New Deal and public works programs promoted by fascism, arguing that fascism similarly arose in response to the threat of socialist revolution and aimed to "save capitalism" and private property.

Socialism

Mixed economies understood as a mixture of socially owned and private enterprises have been predicted and advocated by various socialists as a necessary transitional form between capitalism and socialism. Additionally, several proposals for socialist systems call for a mixture of different forms of enterprise ownership including a role for private enterprise. For example, Alexander Nove's conception of feasible socialism outlines an economic system based on a combination of state enterprises for large industries, worker and consumer cooperatives, private enterprises for small-scale operations, and individually-owned enterprises. The social democratic theorist Eduard Bernstein advocated a form of a mixed economy, believing that a mixed system of state-owned enterprises, cooperatives, and private enterprises would be necessary for a long period before capitalism would evolve of its own accord into socialism.

Following the Russian Civil War, Vladimir Lenin adopted the New Economic Policy in the Soviet Union; the introduction of a mixed economy serving as a temporary expedient for rebuilding the nation. The policy eased the restrictions of war communism and allowed a return of markets, where private individuals could administer small and medium-sized enterprises, while the state would control large industries, banks and foreign trade. The Socialist Republic of Vietnam describes its economy as a socialist-oriented market economy that consists of a mixture of public, private, and cooperative enterprise—a mixed economy that is oriented toward the long-term development of a socialist economy. The People's Republic of China adopted a socialist market economy, which represents an early stage of socialist development according to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The CCP takes the Marxist–Leninist position that an economic system containing diverse forms of ownership—but with the public sector playing a decisive role—is a necessary characteristic of an economy in the preliminary stage of developing socialism.

In the early post-war era in Western Europe, social democratic parties rejected the Stalinist political and economic model then current in the Soviet Union, committing themselves either to an alternative path to socialism or to a compromise between capitalism and socialism. In this period, social democrats embraced a mixed economy based on the predominance of private property and a minority of essential utilities and public services under public ownership. As a result, social democracy became associated with Keynesian economics, state interventionism, and the welfare state. Social democratic governments in practice largely maintain the capitalist mode of production (factor markets, private property, and wage labor) under a mixed economy, and pledge to reform capitalism and make society more egalitarian and democratic.

Typology

Mix of free markets and state intervention

This meaning of a mixed economy refers to a combination of market forces with state intervention in the form of regulations, macroeconomic policies and social welfare interventions aimed at improving market outcomes. As such, this type of mixed economy falls under the framework of a capitalistic market economy, with macroeconomic interventions aimed at promoting the stability of capitalism. Other examples of common government activity in this form of mixed economy include environmental protection, maintenance of employment standards, a standardized welfare system, and economic competition with antitrust laws. Most contemporary market-oriented economies fall under this category, including the economy of the United States. The term is also used to describe the economies of countries that feature extensive welfare states, such as the Nordic model practiced by the Nordic countries, which combine free markets with an extensive welfare state.

The American School is the economic philosophy that dominated United States national policies from the time of the American Civil War until the mid-20th century. It consisted of three core policy initiatives: protecting industry through high tariffs (1861–1932; changing to subsidies and reciprocity from 1932–the 1970s), government investment in infrastructure through internal improvements, and a national bank to promote the growth of productive enterprises. During this period, the United States grew into the largest economy in the world, surpassing the United Kingdom by 1880. The social market economy is the economic policy of modern Germany that steers a middle path between the goals of social democracy and capitalism within the framework of a private market economy and aims at maintaining a balance between a high rate of economic growth, low inflation, low levels of unemployment, good working conditions, and public welfare and public services by using state intervention. Under its influence, Germany emerged from desolation and defeat to become an industrial giant within the European Union.

Mix of private and public enterprise

This type of mixed economy specifically refers to a mixture of private and public ownership of industry and the means of production. As such, it is sometimes described as a "middle path" or transitional state between capitalism and socialism but can also refer to a mixture of state capitalism with private capitalism. Examples include the economies of China, Norway, Singapore, and Vietnam—all of which feature large state-owned enterprise sectors operating alongside large private sectors. The French economy featured a large state sector from 1945 until 1986, mixing a substantial amount of state-owned enterprises and nationalized firms with private enterprises.

Following the Chinese economic reforms initiated in 1978, the Chinese economy has reformed its state-owned enterprises and allowed greater scope for private enterprises to operate alongside the state and collective sectors. In the 1990s, the central government concentrated its ownership in strategic sectors of the economy, but local and provincial level state-owned enterprises continue to operate in almost every industry including information technology, automobiles, machinery, and hospitality. The latest round of state-owned enterprise reform initiated in 2013 stressed increased dividend payouts of state enterprises to the central government and mixed-ownership reform which includes partial private investment into state-owned firms. As a result, many nominally private-sector firms are partially state-owned by various levels of government and state institutional investors, and many state-owned enterprises are partially privately owned resulting in a mixed ownership economy.

Mix of markets and economic planning

This type of mixed economy refers to a combination of economic planning with market forces for the guiding of production in an economy and may coincide with a mixture of private and public enterprise. It can include capitalist economies with indicative macroeconomic planning policies and socialist planned economies that introduced market forces into their economies such as in Hungary's Goulash Communism, which inaugurated the New Economic Mechanism reforms in 1968 that introduced market processes into its planned economy. Under this system, firms were still publicly owned but not subject to physical production targets and output quotas specified by a national plan. Firms were attached to state ministries that had the power to merge, dissolve and reorganize them and which established the firm's operating sector. Enterprises had to acquire their inputs and sell their outputs in markets, eventually eroding away at the Soviet-style planned economy. Dirigisme was an economic policy initiated under Charles de Gaulle in France, designating an economy where the government exerts strong directive influence through indicative planning. In the period of dirigisme, the French state used indicative economic planning to supplement market forces for guiding its market economy. It involved state control of industries such as transportation, energy and telecommunication infrastructures as well as various incentives for private corporations to merge or engage in certain projects. Under its influence, France experienced what is called Thirty Glorious Years of profound economic growth.

Green New Deal (GND) proposals call for social and economic reforms to address climate change and economic inequality using economic planning with market forces for the guiding of production. The reforms involve phasing out fossil fuels through the implementation of a carbon price and emission regulations, while increasing state spending on renewable energy. Additionally, it calls for greater welfare spending, public housing, and job security. GND proposals seek to maintain capitalism but involve economic planning to reduce carbon emissions and inequality through increased taxation, social spending, and state ownership of essential utilities such as the electrical grid.

Within political discourse, mixed economies are supported by people of various political leanings, particularly the centre-left and centre-right. Debate reigns over the appropriate levels of private and public ownership, capitalism and socialism, and government planning within an economy. The centre-left usually supports markets but argues for a higher degree of regulation, public ownership, and planning within an economy. The centre-right generally accepts some level of public ownership and government intervention but argues for lower government regulation and greater privatisation. In 2010, Australian economist John Quiggin wrote: "The experience of the twentieth century suggests that a mixed economy will outperform both central planning and laissez-faire. The real question for policy debates is one of determining the appropriate mix and the way in which the public and private sectors should interact."

Criticism

Numerous economists have questioned the validity of the entire concept of a mixed economy when understood to be a mixture of capitalism and socialism. Critics who argue that capitalism and socialism cannot coexist believe either market logic or economic planning must be prevalent within an economy.

In Human Action, Ludwig von Mises argued that there can be no mixture of capitalism and socialism. Mises elaborated on this point by contending that even if a market economy contained numerous state-run or nationalized enterprises, this would not make the economy mixed because the existence of such organizations does not alter the fundamental characteristics of the market economy. These publicly owned enterprises would still be subject to market sovereignty as they would have to acquire capital goods through markets, strive to maximize profits, or at the least try to minimize costs, and utilize monetary accounting for economic calculation. Friedrich von Hayek and Mises argued that there can be no lasting middle ground between economic planning and a market economy, and any move in the direction of socialist planning is an unintentional move toward what Hilaire Belloc called "the servile state".

Classical and orthodox Marxist theorists also dispute the viability of a mixed economy as a middle ground between socialism and capitalism. Irrespective of enterprise ownership, either the capitalist law of value and accumulation of capital drive the economy or conscious planning and non-monetary forms of valuation, such as calculation in kind, ultimately drive the economy. From the Great Depression onward, extant mixed economies in the Western world are still functionally capitalist because the economic system remains based on competition and profit production.