From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

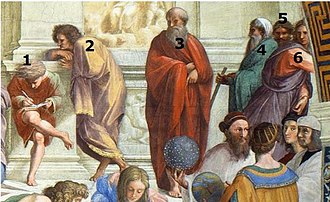

Eliminativists

argue that modern belief in the existence of mental phenomena is

analogous to the ancient belief in obsolete theories such as the

geocentric model of the universe.

Eliminative materialism (also called eliminativism) is a materialist position in the philosophy of mind. It is the idea that the majority of mental states in folk psychology do not exist. Some supporters of eliminativism argue that no coherent neural basis will be found for many everyday psychological concepts such as belief or desire, since they are poorly defined. The argument is that psychological concepts of behavior and experience should be judged by how well they reduce to the biological level. Other versions entail the nonexistence of conscious mental states such as pain and visual perceptions.

Eliminativism about a class of entities is the view that the class of entities does not exist. For example, materialism tends to be eliminativist about the soul; modern chemists are eliminativist about phlogiston; and modern physicists are eliminativist about luminiferous ether. Eliminative materialism

is the relatively new (1960s–70s) idea that certain classes of mental

entities that common sense takes for granted, such as beliefs, desires,

and the subjective sensation of pain, do not exist. The most common versions are eliminativism about propositional attitudes, as expressed by Paul and Patricia Churchland, and eliminativism about qualia (subjective interpretations about particular instances of subjective experience), as expressed by Daniel Dennett, Georges Rey, and Jacy Reese Anthis. These philosophers often appeal to an introspection illusion.

In the context of materialist understandings of psychology, eliminativism is the opposite of reductive materialism, arguing that mental states as conventionally understood do exist, and directly correspond to the physical state of the nervous system. An intermediate position, revisionary materialism, often argues the mental state in question will prove to be somewhat reducible to physical phenomena—with some changes needed to the commonsense concept.

Since eliminative materialism arguably claims that future

research will fail to find a neuronal basis for various mental

phenomena, it may need to wait for science to progress further. One

might question the position on these grounds, but philosophers like

Churchland argue that eliminativism is often necessary in order to open

the minds of thinkers to new evidence and better explanations. Views closely related to eliminativism include illusionism and quietism.

Overview

Various

arguments have been made for and against eliminative materialism over

the last 50 years. The view's history can be traced to David Hume, who rejected the idea of the "self" on the grounds that it was not based on any impression.

Most arguments for the view are based on the assumption that people's

commonsense view of the mind is actually an implicit theory. It is to be

compared and contrasted with other scientific theories in its

explanatory success, accuracy, and ability to predict the future.

Eliminativists argue that commonsense "folk" psychology has failed and

will eventually need to be replaced by explanations derived from

neuroscience. These philosophers therefore tend to emphasize the

importance of neuroscientific research as well as developments in artificial intelligence.

Philosophers who argue against eliminativism may take several approaches. Simulation theorists, like Robert Gordon and Alvin Goldman,

argue that folk psychology is not a theory, but depends on internal

simulation of others, and therefore is not subject to falsification in

the same way that theories are. Jerry Fodor, among others,

argues that folk psychology is, in fact, a successful (even

indispensable) theory. Another view is that eliminativism assumes the

existence of the beliefs and other entities it seeks to "eliminate" and

is thus self-refuting.

Schematic overview: Eliminativists suggest that some sciences can be

reduced (blue), but that theories that are in principle irreducible will eventually be eliminated (orange).

Eliminativism maintains that the commonsense understanding of the mind is mistaken, and that neuroscience

will one day reveal that mental states talked about in everyday

discourse, using words such as "intend", "believe", "desire", and

"love", do not refer to anything real. Because of the inadequacy of

natural languages, people mistakenly think that they have such beliefs

and desires. Some eliminativists, such as Frank Jackson, claim that consciousness does not exist except as an epiphenomenon of brain function; others, such as Georges Rey, claim that the concept will eventually be eliminated as neuroscience progresses.

Consciousness and folk psychology are separate issues, and it is

possible to take an eliminative stance on one but not the other. The roots of eliminativism go back to the writings of Wilfred Sellars, W.V.O. Quine, Paul Feyerabend, and Richard Rorty. The term "eliminative materialism" was first introduced by James Cornman in 1968 while describing a version of physicalism endorsed by Rorty. The later Ludwig Wittgenstein

was also an important inspiration for eliminativism, particularly with

his attack on "private objects" as "grammatical fictions".

Early eliminativists such as Rorty and Feyerabend often confused

two different notions of the sort of elimination that the term

"eliminative materialism" entailed. On the one hand, they claimed, the cognitive sciences

that will ultimately give people a correct account of the mind's

workings will not employ terms that refer to commonsense mental states

like beliefs and desires; these states will not be part of the ontology of a mature cognitive science. But critics immediately countered that this view was indistinguishable from the identity theory of mind. Quine himself wondered what exactly was so eliminative about eliminative materialism:

Is physicalism a repudiation of

mental objects after all, or a theory of them? Does it repudiate the

mental state of pain or anger in favor of its physical concomitant, or

does it identify the mental state with a state of the physical organism

(and so a state of the physical organism with the mental state)?

On the other hand, the same philosophers claimed that commonsense

mental states simply do not exist. But critics pointed out that

eliminativists could not have it both ways: either mental states exist

and will ultimately be explained in terms of lower-level

neurophysiological processes, or they do not. Modern eliminativists have much more clearly expressed the view that

mental phenomena simply do not exist and will eventually be eliminated

from people's thinking about the brain in the same way that demons have

been eliminated from people's thinking about mental illness and

psychopathology.

While it was a minority view in the 1960s, eliminative materialism gained prominence and acceptance during the 1980s. Proponents of this view, such as B.F. Skinner, often made parallels to previous superseded scientific theories (such as that of the four humours, the phlogiston theory of combustion, and the vital force

theory of life) that have all been successfully eliminated in

attempting to establish their thesis about the nature of the mental. In

these cases, science has not produced more detailed versions or

reductions of these theories, but rejected them altogether as obsolete. Radical behaviorists, such as Skinner, argued that folk psychology is already obsolete and should be replaced by descriptions of histories of reinforcement and punishment. Such views were eventually abandoned. Patricia and Paul Churchland argued that folk psychology will be gradually replaced as neuroscience matures.

Eliminativism is not only motivated by philosophical

considerations, but is also a prediction about what form future

scientific theories will take. Eliminativist philosophers therefore tend

to be concerned with data from the relevant brain and cognitive sciences.

In addition, because eliminativism is essentially predictive in nature,

different theorists can and often do predict which aspects of folk

psychology will be eliminated from folk psychological vocabulary. None

of these philosophers are eliminativists tout court.

Today, the eliminativist view is most closely associated with the Churchlands, who deny the existence of propositional attitudes (a subclass of intentional states), and with Daniel Dennett, who is generally considered an eliminativist about qualia

and phenomenal aspects of consciousness. One way to summarize the

difference between the Churchlands' view and Dennett's is that the

Churchlands are eliminativists about propositional attitudes, but reductionists about qualia, while Dennett is an anti-reductionist about propositional attitudes and an eliminativist about qualia.

More recently, Brian Tomasik and Jacy Reese Anthis have made various arguments for eliminativism.[ Elizabeth Irvine has argued that both science and folk psychology do not treat mental states

as having phenomenal properties so the hard problem "may not be a

genuine problem for non-philosophers (despite its overwhelming

obviousness to philosophers), and questions about consciousness may well

'shatter' into more specific questions about particular capacities." In 2022, Anthis published Consciousness Semanticism: A Precise Eliminativist Theory of Consciousness,

which asserts that "formal argumentation from precise semantics"

dissolves the hard problem because of the contradiction between

precision implied in philosophical theory and the vagueness in its

definition, which implies there is no fact of the matter for

phenomenological consciousness.

Arguments for eliminativism

Problems with folk theories

Eliminativists such as Paul and Patricia Churchland argue that folk psychology

is a fully developed but non-formalized theory of human behavior. It is

used to explain and make predictions about human mental states and

behavior. This view is often referred to as the theory of mind or just simply theory-theory, for it theorizes the existence of an unacknowledged theory. As a theory

in the scientific sense, eliminativists maintain, folk psychology must

be evaluated on the basis of its predictive power and explanatory

success as a research program for the investigation of the mind/brain.

Such eliminativists have developed different arguments to show

that folk psychology is a seriously mistaken theory and should be

abolished. They argue that folk psychology excludes from its purview or

has traditionally been mistaken about many important mental phenomena

that can and are being examined and explained by modern neuroscience.

Some examples are dreaming, consciousness, mental disorders, learning processes, and memory

abilities. Furthermore, they argue, folk psychology's development in

the last 2,500 years has not been significant and it is therefore

stagnant. The ancient Greeks

already had a folk psychology comparable to modern views. But in

contrast to this lack of development, neuroscience is rapidly

progressing and, in their view, can explain many cognitive processes that folk psychology cannot.

Folk psychology retains characteristics of now obsolete theories

or legends from the past. Ancient societies tried to explain the

physical mysteries of nature

by ascribing mental conditions to them in such statements as "the sea

is angry". Gradually, these everyday folk psychological explanations

were replaced by more efficient scientific descriptions. Today,

eliminativists argue, there is no reason not to accept an effective

scientific account of cognition. If such an explanation existed, then

there would be no need for folk-psychological explanations of behavior,

and the latter would be eliminated the same way as the mythological explanations the ancients used.

Another line of argument is the meta-induction based on what

eliminativists view as the disastrous historical record of folk theories

in general. Ancient pre-scientific "theories" of folk biology, folk

physics, and folk cosmology have all proven radically wrong.

Eliminativists argue the same in the case of folk psychology. There

seems no logical basis, to the eliminativist, to make an exception just

because folk psychology has lasted longer and is more intuitive or

instinctively plausible than other folk theories.

Indeed, the eliminativists warn, considerations of intuitive

plausibility may be precisely the result of the deeply entrenched nature

in society of folk psychology itself. It may be that people's beliefs

and other such states are as theory-laden as external perceptions and

hence that intuitions will tend to be biased in their favor.

Specific problems with folk psychology

Much of folk psychology involves the attribution of intentional states (or more specifically as a subclass, propositional attitudes).

Eliminativists point out that these states are generally ascribed

syntactic and semantic properties. An example of this is the language of thought

hypothesis, which attributes a discrete, combinatorial syntax and other

linguistic properties to these mental phenomena. Eliminativists argue

that such discrete, combinatorial characteristics have no place in

neuroscience, which speaks of action potentials, spiking frequencies,

and other continuous and distributed effects. Hence, the syntactic

structures assumed by folk psychology have no place in such a structure

as the brain.

To this there have been two responses. On the one hand, some

philosophers deny that mental states are linguistic and see this as a straw man argument. The other view is represented by those who subscribe to "a language of thought". They assert that mental states can be multiply realized and that functional characterizations are just higher-level characterizations of what happens at the physical level.

It has also been argued against folk psychology that the

intentionality of mental states like belief imply that they have

semantic qualities. Specifically, their meaning is determined by the

things they are about in the external world. This makes it difficult to

explain how they can play the causal roles they are supposed to in

cognitive processes.

In recent years, this latter argument has been fortified by the theory of connectionism.

Many connectionist models of the brain have been developed in which the

processes of language learning and other forms of representation are

highly distributed and parallel. This tends to indicate that such

discrete and semantically endowed entities as beliefs and desires are

unnecessary.

Physics eliminates intentionality

If

a thought is a kind of neural process, then when one thinks about

Paris, some network of neurons is somehow about Paris. Consider various

accounts of this possibility. The neurons cannot be about Paris in the

way a picture is, because unlike a picture, they do not resemble Paris.

But neither can they be about Paris in the way that a red octagonal stop

sign is about stopping even though it does not resemble that action.

For a red octagon, or the word "stop" for that matter, only mean what

they do as a matter of convention, only because we interpret the shapes

in question as representing the action of stopping. And when you think

about Paris, no one is assigning a conventional interpretation to

such-and-such neurons in your brain so as to make them represent Paris.

To suggest that some further brain process assigns such a meaning to the

purported "Paris neurons" is merely to commit a homunculus fallacy and

explains nothing. For if we say that one clump of neurons assigns

meaning to another, we are saying that the one represents the other as

having such-and-such a meaning. That means that we now have to explain

how the first possesses the meaning or representational content by

virtue of which it does that, which entails that we have not solved the

first problem but only added a second one. We have "explained" the

meaning of one clump of neurons by reference to meaning implicitly

present in another clump, and thus merely initiated a vicious

explanatory regress. The only way to break the regress is to postulate

some bit of matter that just has its meaning intrinsically, without

deriving it from anything else. But there can be no such bit of matter,

because physics has ruled out the existence of clumps of matter of that

sort.

Evolution eliminates intentionality

Any naturalistic, purely causal, non-semantic account of content must rely on Darwinian natural selection

to build neural states capable of storing unique propositions, as

required by folk psychology. Theories that attempt to account for intentionality

within materialism face the disjunction problem, which results in the

indeterminacy of propositional content. If such theories cannot solve

the disjunction problem, then neurons cannot store unique propositions.

The only process that can build neural circuits, evolution by natural

selection, cannot solve the disjunction problem. The whole point of

Darwin's theory is that in the creation of adaptations, nature is not

active but passive. What is really going on is environmental

filtration—a purely passive and not very discriminating process that

prevents most traits below some minimal local threshold from persisting.

Natural selection is selection against. Selection for

requires foresight, planning, and purpose. Darwin's achievement was to

show that the appearance of purpose belies the reality of purposeless,

unforesighted, unplanned, mindless causation. All adaptation requires is

selection against. That was Darwin's point. But the combination of

blind variation and selection against is not possible without

disjunctive outcomes.

It is important that selection against is not the contradictory

of selection for, i.e. that selection against trait T is not just

selection for trait not-T. This is because there are traits that are

neither selected against nor selected for: the neutral ones that

biologists, especially molecular evolutionary biologists, call silent,

switched off, junk, non-coding, etc. Selection for and selection against

are contraries, not contradictories.

Natural selection cannot discriminate between coextensive

properties. To see how Darwinian selection against works in a real case,

consider two distinct gene products, one of which is neutral or even

harmful to an organism and the other of which is beneficial, that are

coded for by adjacent genes on the chromosomes. This is the phenomenon

of genetic linkage. The traits that the genes coded for will be

coextensive in a population because the gene-types are coextensive in

that population. Mendelian assortment and segregation do not break up

these packages of genes with any efficiency. Only crossover, the

breaking up and faulty re-annealing of chromosomal strings or similar

processes, can do this. As Darwin realized, no process producing

variants in nature picks up on future usefulness, convenience, need, or

adaptational value. The only thing evolution (natural selection-against)

can do about the free-riding maladaptive or neutral trait, whose genes

are riding along close to the genes for an adaptive trait, is wait

around for the genetic material to be broken at just the right place,

between the genes. Once this happens, Darwinian processes can begin to

tell the difference between them. But only when environmental

vicissitudes break up the DNA on which the two adjacent genes sit can

selection against get started—if one of the two proteins is harmful.

Darwinian theory's disjunction problem is that the process Darwin

discovered cannot tell the difference between these two genes or their

traits until crossover breaks the linkage between one gene, which is

going to increase its frequency, and the other, which is going to

decrease its frequency. If they are never separated, it will remain

blind to their differences forever. What is worse, and more likely, one

gene sequence can code for a favorable trait—a protein required for

survival—while part of the same sequence can code for a maladaptive

trait—some gene product that reduces fitness. Natural selection will

have an even harder time discriminating between these two traits. Since

evolution cannot solve the disjunction problem, the right conclusion for

the materialist is to accept eliminativism by denying that neural

states have as their informational content specific, particular,

determinate statements that attribute non-disjunctive properties and

relations to non-disjunctive subjects.

Arguments against eliminativism

Intentionality and consciousness are identical

Some

eliminativists reject intentionality while accepting the existence of

qualia. Other eliminativists reject qualia while accepting

intentionality. Many philosophers argue that intentionality cannot exist

without consciousness and vice versa, and so any philosopher who

accepts one while rejecting the other is being inconsistent. They argue

that, to be consistent, one must accept both qualia and intentionality

or reject them both. Philosophers who argue for such a position include Philip Goff, Terence Horgan, Uriah Kriegal, and John Tienson. The philosopher Keith Frankish

accepts the existence of intentionality but holds to illusionism about

consciousness because he rejects qualia. Goff notes that beliefs are a

kind of propositional thought.

Intuitive reservations

The

thesis of eliminativism seems so obviously wrong to many critics, who

find it undeniable that people know immediately and indubitably that

they have minds, that argumentation seems unnecessary. This sort of

intuition-pumping is illustrated by asking what happens when one asks

oneself honestly if one has mental states.

Eliminativists object to such a rebuttal of their position by claiming

that intuitions often are mistaken. Analogies from the history of

science are frequently invoked to buttress this observation: it may

appear obvious that the sun travels around the earth, for example, but

this was nevertheless proved wrong. Similarly, it may appear obvious

that apart from neural events there are also mental conditions, but that

could be false.

But even if one accepts the susceptibility to error of people's

intuitions, the objection can be reformulated: if the existence of

mental conditions seems perfectly obvious and is central to our

conception of the world, then enormously strong arguments are needed to

deny their existence. Furthermore, these arguments, to be consistent,

must be formulated in a way that does not presuppose the existence of

entities like "mental states", "logical arguments", and "ideas", lest

they be self-contradictory.

Those who accept this objection say that the arguments for

eliminativism are far too weak to establish such a radical claim and

that there is thus no reason to accept eliminativism.

Self-refutation

Some philosophers, such as Paul Boghossian, have attempted to show that eliminativism is in some sense self-refuting, since the theory presupposes the existence of mental phenomena. If eliminativism is true, then eliminativists must accept an intentional property like truth,

supposing that in order to assert something one must believe it. Hence,

for eliminativism to be asserted as a thesis, the eliminativist must

believe that it is true; if so, there are beliefs, and eliminativism is

false.

Georges Rey and Michael Devitt reply to this objection by invoking deflationary semantic theories that avoid analyzing predicates

like "x is true" as expressing a real property. They are instead

construed as logical devices, so that asserting that a sentence is true

is just a quoted way of asserting the sentence itself. To say "'God

exists' is true" is just to say "God exists". This way, Rey and Devitt

argue, insofar as dispositional replacements of "claims" and

deflationary accounts of "true" are coherent, eliminativism is not

self-refuting.

Correspondence theory of truth

Several philosophers, such as the Churchlands and Alex Rosenberg,

have developed a theory of structural resemblance or physical

isomorphism that could explain how neural states can instantiate truth

within the correspondence theory of truth.

Neuroscientists use the word "representation" to identify the neural

circuits' encoding of inputs from the peripheral nervous system in, for

example, the visual cortex. But they use the word without according it

any commitment to intentional content. In fact, there is an explicit

commitment to describing neural representations in terms of structures

of neural axonal discharges that are physically isomorphic to the inputs

that cause them. Suppose that this way of understanding representation

in the brain is preserved in the long-term course of research providing

an understanding of how the brain processes and stores information. Then

there will be considerable evidence that the brain is a neural network

whose physical structure is identical to the aspects of its environment

it tracks and whose representations of these features consist in this

physical isomorphism.

Experiments in the 1980s with macaques

isolated the structural resemblance between input vibrations the finger

feels, measured in cycles per second, and representations of them in

neural circuits, measured in action-potential spikes per second. This

resemblance between two easily measured variables makes it unsurprising

that they would be among the first such structural resemblances to be

discovered. Macaques and humans have the same peripheral nervous system

sensitivities and can make the same tactile discriminations. Subsequent

research into neural processing has increasingly vindicated a structural

resemblance or physical isomorphism approach to how information enters

the brain and is stored and deployed.

This isomorphism between brain and world is not a matter of some

relationship between reality and a map of reality stored in the brain.

Maps require interpretation if they are to be about what they map, and

eliminativism and neuroscience share a commitment to explaining the

appearance of aboutness by purely physical relationships between

informational states in the brain and what they "represent". The

brain-to-world relationship must be a matter of physical

isomorphism—sameness of form, outline, structure—that does not require

interpretation.

This machinery can be applied to make "sense" of eliminativism in

terms of the sentences eliminativists say or write. When we say that

eliminativism is true, that the brain does not store information in the

form of unique sentences, statements, expressing propositions or

anything like them, there is a set of neural circuits that has no

trouble coherently carrying this information. There is a possible

translation manual that will guide us back from the vocalization or

inscription eliminativists express to these circuits. These neural

structures will differ from the neural circuits of those who explicitly

reject eliminativism in ways that our translation manual will presumably

shed some light on, giving us a neurological handle on disagreement and

on the structural differences in neural circuitry, if any, between

asserting p and asserting not-p when p expresses the eliminativist

thesis.

Criticism

The

physical isomorphism approach faces indeterminacy problems. Any given

structure in the brain will be causally related to, and isomorphic in

various respects to, many different structures in external reality. But

we cannot discriminate the one it is intended to represent or that it is

supposed to be true "of". These locutions are heavy with just the

intentionality that eliminativism denies. Here is a problem of

underdetermination or holism that eliminativism shares with

intentionality-dependent theories of mind. Here, we can only invoke

pragmatic criteria for discriminating successful structural

representations—the substitution of true ones for unsuccessful ones—the

ones we used to call false.

Dennett notes that it is possible that such indeterminacy

problems remain only hypothetical, not occurring in reality. He

constructs a 4x4 "Quinian crossword puzzle" with words that must satisfy

both the across and down definitions. Since there are multiple

constraints on this puzzle, there is one solution. Thus we can think of

the brain and its relation to the external world as a very large

crossword puzzle that must satisfy exceedingly many constraints to which

there is only one possible solution. Therefore, in reality we may end

up with only one physical isomorphism between the brain and the external

world.

Pragmatic theory of truth

When

indeterminacy problems arose because the brain is physically isomorphic

to multiple structures of the external world, it was urged that a

pragmatic approach be used to resolve the problem. Another approach

argues that we the pragmatic theory of truth should be used from the start to decide whether certain neural circuits store true information about the external world. Pragmatism was founded by Charles Sanders Peirce and William James, and later refined by our understanding of the philosophy of science. According to pragmatism, to say that general relativity is true is to say that it makes more accurate predictions than other theories (Newtonian mechanics, Aristotle's physics,

etc.). If computer circuits lack intentionality and do not store

information using propositions, then in what sense can computer A have

true information about the world while computer B lacks it? If the

computers were instantiated in autonomous cars,

we could test whether A or B successfully complete a cross-country road

trip. If A succeeds while B fails, the pragmatist can say that A holds

true information about the world, because A's information allows it to

make more accurate predictions (relative to B) about the world and to

move around its environment more successfully. Similarly, if brain A has

information that enables the biological organism to make more accurate

predictions about the world and helps the organism successfully move

around in the environment, then A has true information about the world.

Although not advocates of eliminativism, John Shook and Tibor Solymosi

argue that pragmatism is a promising program for understanding

advancements in neuroscience and integrating them into a philosophical

picture of the world.

Criticism

The

reason naturalism cannot be pragmatic in its epistemology starts with

its metaphysics. Science tells us that we are components of the natural

realm, indeed latecomers in the 13.8-billion-year-old universe. The

universe was not organized around our needs and abilities, and what

works for us is just a set of contingent facts that could have been

otherwise. Among the sciences' explananda of the set of things that work

for us. Once we have begun discovering things about the universe that

work for us, science sets out to explain why they do. It is clear that

one explanation for why things work for us that we must rule out as

unilluminating, indeed question-begging, is that they work for us

because they work for us. If something works for us, enables us to meet

our needs and wants, there must be an explanation reflecting facts about

us and the world that produce the needs and the means to satisfy them.

The explanation of why scientific methods work for us must be a

causal explanation. It must show what facts about reality make the

methods we employ to acquire knowledge suitable for doing so. The

explanation must show that our methods work —for example, have reliable

technological application— not by coincidence, still less miracle or

accident. That means there must be some facts, events, processes that

operate in reality and brought about our pragmatic success. The demand

that success be explained is a consequence of science's epistemology. If

the truth of such explanations consists in the fact that they work for

us (as pragmatism requires), then the explanation of why our scientific

methods work is that they work. That is not a satisfying explanation.

Qualia

Another problem for the eliminativist is the consideration that human beings undergo subjective experiences and hence their conscious mental states have qualia.

Since qualia are generally regarded as characteristics of mental

states, their existence does not seem compatible with eliminativism. Eliminativists such as Dennett and Rey respond by rejecting qualia.

Opponents of eliminativism see this response as problematic, since many

claim that existence of qualia is perfectly obvious. Many philosophers

consider the "elimination" of qualia implausible, if not

incomprehensible. They assert that, for instance, the existence of pain

is simply beyond denial.

Admitting that the existence of qualia seems obvious, Dennett

nevertheless holds that "qualia" is a theoretical term from an outdated

metaphysics stemming from Cartesian

intuitions. He argues that a precise analysis shows that the term is in

the long run empty and full of contradictions. Eliminativism's claim

about qualia is that there is no unbiased evidence for such experiences

when regarded as something more than propositional attitudes.

In other words, it does not deny that pain exists, but holds that it

exists independently of its effect on behavior. Influenced by

Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations, Dennett and Rey have defended eliminativism about qualia even when other aspects of the mental are accepted.

Quining qualia

Dennett offers philosophical thought experiments to argue that qualia do not exist. First he lists five properties of qualia:

- They are "directly" or "immediately" graspable during our conscious experiences.

- We are infallible about them.

- They are "private": no one can directly access anyone else's qualia.

- They are ineffable.

- They are "intrinsic" and "simple" or "unanalyzable."

Inverted qualia

The first thought experiment Dennett uses to demonstrate that qualia lack the listed necessary properties to exist involves inverted qualia:

consider two people who have different qualia but the same external

physical behavior. But now the qualia supporter can present an

"intrapersonal" variation. Suppose a neurosurgeon works on your brain

and you discover that grass now looks red. Would this not be a case

where we could confirm the reality of qualia—by noticing how the qualia

have changed while every other aspect of our conscious experience

remains the same? Not quite, Dennett replies via the next intuition

pump, "alternative neurosurgery". There are two different ways the

neurosurgeon might have accomplished the inversion. First, they might

have tinkered with something "early on", so that signals from the eye

when you look at grass contain the information "red" rather than

"green". This would result in genuine qualia inversion. But they might

instead have tinkered with your memory. Here your qualia would remain

the same, but your memory would be altered so that your current green

experience would contradict your earlier memories of grass. You would

still feel that the color of grass had changed, but here the qualia have

not changed, but your memories have. Would you be able to tell which of

these scenarios is correct? No: your perceptual experience tells you

that something has changed but not whether your qualia have changed.

Dennett concludes, since (by hypothesis) the two surgical procedures can

yield exactly the same introspective effects while only one inverts the

qualia, nothing in the subject's experience can favor one hypothesis

over the other. So unless he seeks outside help, the state of his own

qualia must be as unknowable to him as the state of anyone else's. It is

questionable, in short, that we have direct, infallible access to our

conscious experience.

The experienced beer drinker

Dennett's

second thought experiment involves beer. Many people think of beer as

an acquired taste: one's first sip is often unpleasant, but one

gradually comes to enjoy it. But wait, Dennett asks—what is the "it"

here? Compare the flavor of that first taste with the flavor now. Does

the beer taste exactly the same both then and now, only now you like

that taste whereas before you disliked it? Or is it that the way beer

tastes gradually shifts—so that the taste you did not like at the

beginning is not the same taste you now like? In fact most people simply

cannot tell which is the correct analysis. But that is to give up again

on the idea that we have special and infallible access to our qualia.

Further, when forced to choose, many people feel that the second

analysis is more plausible. But then if one's reactions to an experience

are in any way constitutive of it, the experience is not so "intrinsic"

after all—and another qualia property falls.

Inverted goggles

Dennett's

third thought experiment involves inverted goggles. Scientists have

devised special eyeglasses that invert up and down for the wearer. When

you put them on, everything looks upside down. When subjects first put

them on, they can barely walk around without stumbling. But after

subjects wear them for a while, something surprising occurs. They adapt

and become able to walk around as easily as before. When you ask them

whether they adapted by re-inverting their visual field or simply got

used to walking around in an upside-down world, they cannot say. So as

in our beer-drinking case, either we simply do not have the special,

infallible access to our qualia that would allow us to distinguish the

two cases or the way the world looks to us is actually a function of how

we respond to the world—in which case qualia are not "intrinsic"

properties of experience.

Criticism

Edward

Feser objects to Dennett's position as follows. That you need to appeal

to third-person neurological evidence to determine whether your memory

of your qualia has been tampered with does not seem to show that your

qualia themselves—past or present—can be known only by appealing to that

evidence. You might still be directly aware of your qualia from the

first-person, subjective point of view even if you do not know whether

they are the same as the qualia you had yesterday—just as you might

really be aware of the article in front of you even if you do not know

whether it is the same as the article you saw yesterday. Questions about

memory do not necessarily bear on the nature of your awareness of

objects present here and now (even if they bear on what you can

justifiably claim to know about such objects), whatever those objects

happen to be. Dennett's assertion that scientific objectivity requires

appealing exclusively to third-person evidence appears mistaken. What

scientific objectivity requires is not denial of the first-person

subjective point of view but rather a means of communicating

inter-subjectively about what one can grasp only from that point of

view. Given the relational structure first-person phenomena like qualia

appear to exhibit—a structure that Carnap

devoted great effort to elucidating—such a means seems available: we

can communicate what we know about qualia in terms of their structural

relations to one another. Dennett fails to see that qualia can be

essentially subjective and still relational or non-intrinsic, and thus

communicable. This communicability ensures that claims about qualia are

epistemologically objective; that is, they can in principle be grasped

and evaluated by all competent observers even though they are claims

about phenomena that are arguably not metaphysically objective, i.e.,

about entities that exist only as grasped by a subject of experience. It

is only the former sort of objectivity that science requires. It does

not require the latter, and cannot plausibly require it if the

first-person realm of qualia is what we know better than anything else.

Illusionism

Illusionism is an active program within eliminative materialism to explain phenomenal consciousness as an illusion. It is promoted by the philosophers Daniel Dennett, Keith Frankish, and Jay Garfield, and the neuroscientist Michael Graziano. Graziano has advanced the attention schema theory of consciousness and postulates that consciousness is an illusion. According to David Chalmers,

proponents argue that once we can explain consciousness as an illusion

without the need for a realist view of consciousness, we can construct a

debunking argument against realist views of consciousness. This line of argument draws from other debunking arguments like the evolutionary debunking argument in the field of metaethics. Such arguments note that morality is explained by evolution without positing moral realism, so there is a sufficient basis to debunk moral realism.

Criticism

Illusionists

generally hold that once it is explained why people believe and say

they are conscious, the hard problem of consciousness will dissolve.

Chalmers agrees that a mechanism for these beliefs and reports can and

should be identified using the standard methods of physical science, but

disagrees that this would support illusionism, saying that the datum

illusionism fails to account for is not reports of consciousness but

rather first-person consciousness itself.

He separates consciousness from beliefs and reports about

consciousness, but holds that a fully satisfactory theory of

consciousness should explain how the two are "inextricably intertwined"

so that their alignment does not require an inexplicable coincidence. Illusionism has also been criticized by the philosopher Jesse Prinz.

Efficacy of folk psychology

Some philosophers argue that folk psychology is quite successful.

Simulation theorists doubt that people's understanding of the mental

can be explained in terms of a theory at all. Rather they argue that

people's understanding of others is based on internal simulations of how

they would act and respond in similar situations. Jerry Fodor

believes in folk psychology's success as a theory, because it makes for

an effective way of communication in everyday life that can be

implemented with few words. Such effectiveness could not be achieved

with complex neuroscientific terminology.