Empirical evidence for a proposition is evidence, i.e. what supports or counters this proposition, that is constituted by or accessible to sense experience or experimental procedure. Empirical evidence is of central importance to the sciences and plays a role in various other fields, like epistemology and law.

There is no general agreement on how the terms evidence and empirical are to be defined. Often different fields work with quite different conceptions. In epistemology, evidence is what justifies beliefs or what determines whether holding a certain belief is rational. This is only possible if the evidence is possessed by the person, which has prompted various epistemologists to conceive evidence as private mental states like experiences or other beliefs. In philosophy of science, on the other hand, evidence is understood as that which confirms or disconfirms scientific hypotheses and arbitrates between competing theories. For this role, it is important that evidence is public and uncontroversial, like observable physical objects or events and unlike private mental states, so that evidence may foster scientific consensus. The term empirical comes from Greek ἐμπειρία empeiría, i.e. 'experience'. In this context, it is usually understood as what is observable, in contrast to unobservable or theoretical objects. It is generally accepted that unaided perception constitutes observation, but it is disputed to what extent objects accessible only to aided perception, like bacteria seen through a microscope or positrons detected in a cloud chamber, should be regarded as observable.

Empirical evidence is essential to a posteriori knowledge or empirical knowledge, knowledge whose justification or falsification depends on experience or experiment. A priori knowledge, on the other hand, is seen either as innate or as justified by rational intuition and therefore as not dependent on empirical evidence. Rationalism fully accepts that there is knowledge a priori, which is either outright rejected by empiricism or accepted only in a restricted way as knowledge of relations between our concepts but not as pertaining to the external world.

Scientific evidence is closely related to empirical evidence but not all forms of empirical evidence meet the standards dictated by scientific methods. Sources of empirical evidence are sometimes divided into observation and experimentation, the difference being that only experimentation involves manipulation or intervention: phenomena are actively created instead of being passively observed.

Background

The concept of evidence is of central importance in epistemology and in philosophy of science but plays different roles in these two fields. In epistemology, evidence is what justifies beliefs or what determines whether holding a certain doxastic attitude is rational. For example, the olfactory experience of smelling smoke justifies or makes it rational to hold the belief that something is burning. It is usually held that for justification to work, the evidence has to be possessed by the believer. The most straightforward way to account for this type of evidence possession is to hold that evidence consists of the private mental states possessed by the believer.

Some philosophers restrict evidence even further, for example, to only conscious, propositional or factive mental states. Restricting evidence to conscious mental states has the implausible consequence that many simple everyday beliefs would be unjustified. This is why it is more common to hold that all kinds of mental states, including stored but currently unconscious beliefs, can act as evidence. Various of the roles played by evidence in reasoning, for example, in explanatory, probabilistic and deductive reasoning, suggest that evidence has to be propositional in nature, i.e. that it is correctly expressed by propositional attitude verbs like "believe" together with a that-clause, like "that something is burning". But it runs counter to the common practice of treating non-propositional sense-experiences, like bodily pains, as evidence. Its defenders sometimes combine it with the view that evidence has to be factive, i.e. that only attitudes towards true propositions constitute evidence. In this view, there is no misleading evidence. The olfactory experience of smoke would count as evidence if it was produced by a fire but not if it was produced by a smoke generator. This position has problems in explaining why it is still rational for the subject to believe that there is a fire even though the olfactory experience cannot be considered evidence.

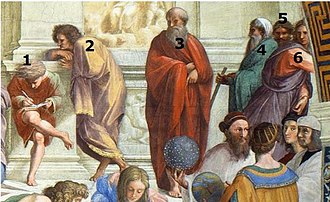

In philosophy of science, evidence is understood as that which confirms or disconfirms scientific hypotheses and arbitrates between competing theories. Measurements of Mercury's "anomalous" orbit, for example, constitute evidence that plays the role of neutral arbiter between Newton's and Einstein's theory of gravitation by confirming Einstein's theory. For scientific consensus, it is central that evidence is public and uncontroversial, like observable physical objects or events and unlike private mental states. This way it can act as a shared ground for proponents of competing theories. Two issues threatening this role are the problem of underdetermination and theory-ladenness. The problem of underdetermination concerns the fact that the available evidence often provides equal support to either theory and therefore cannot arbitrate between them. Theory-ladenness refers to the idea that evidence already includes theoretical assumptions. These assumptions can hinder it from acting as neutral arbiter. It can also lead to a lack of shared evidence if different scientists do not share these assumptions. Thomas Kuhn is an important advocate of the position that theory-ladenness in relation to scientific paradigms plays a central role in science.

Definition

A thing is evidence for a proposition if it epistemically supports this proposition or indicates that the supported proposition is true. Evidence is empirical if it is constituted by or accessible to sensory experience. There are various competing theories about the exact definition of the terms evidence and empirical. Different fields, like epistemology, the sciences or legal systems, often associate different concepts with these terms. An important distinction among theories of evidence is whether they identify evidence with private mental states or with public physical objects. Concerning the term empirical, there is a dispute about where to draw the line between observable or empirical objects in contrast to unobservable or merely theoretical objects.

The traditional view proposes that evidence is empirical if it is constituted by or accessible to sensory experience. This involves experiences arising from the stimulation of the sense organs, like visual or auditory experiences, but the term is often used in a wider sense including memories and introspection. It is usually seen as excluding purely intellectual experiences, like rational insights or intuitions used to justify basic logical or mathematical principles. The terms empirical and observable are closely related and sometimes used as synonyms.

There is an active debate in contemporary philosophy of science as to what should be regarded as observable or empirical in contrast to unobservable or merely theoretical objects. There is general consensus that everyday objects like books or houses are observable since they are accessible via unaided perception, but disagreement starts for objects that are only accessible through aided perception. This includes using telescopes to study distant galaxies, microscopes to study bacteria or using cloud chambers to study positrons. So the question is whether distant galaxies, bacteria or positrons should be regarded as observable or merely theoretical objects. Some even hold that any measurement process of an entity should be considered an observation of this entity. So in this sense, the interior of the sun is observable since neutrinos originating there can be detected. The difficulty with this debate is that there is a continuity of cases going from looking at something with the naked eye, through a window, through a pair of glasses, through a microscope, etc. Because of this continuity, drawing the line between any two adjacent cases seems to be arbitrary. One way to avoid these difficulties is to hold that it is a mistake to identify the empirical with what is observable or sensible. Instead, it has been suggested that empirical evidence can include unobservable entities as long as they are detectable through suitable measurements. A problem with this approach is that it is rather far from the original meaning of "empirical", which contains the reference to experience.

Related concepts

Knowledge a posteriori and a priori

Knowledge or the justification of a belief is said to be a posteriori if it is based on empirical evidence. A posteriori refers to what depends on experience (what comes after experience), in contrast to a priori, which stands for what is independent of experience (what comes before experience). For example, the proposition that "all bachelors are unmarried" is knowable a priori since its truth only depends on the meanings of the words used in the expression. The proposition "some bachelors are happy", on the other hand, is only knowable a posteriori since it depends on experience of the world as its justifier. Immanuel Kant held that the difference between a posteriori and a priori is tantamount to the distinction between empirical and non-empirical knowledge.

Two central questions for this distinction concern the relevant sense of "experience" and of "dependence". The paradigmatic justification of knowledge a posteriori consists in sensory experience, but other mental phenomena, like memory or introspection, are also usually included in it. But purely intellectual experiences, like rational insights or intuitions used to justify basic logical or mathematical principles, are normally excluded from it. There are different senses in which knowledge may be said to depend on experience. In order to know a proposition, the subject has to be able to entertain this proposition, i.e. possess the relevant concepts. For example, experience is necessary to entertain the proposition "if something is red all over then it is not green all over" because the terms "red" and "green" have to be acquired this way. But the sense of dependence most relevant to empirical evidence concerns the status of justification of a belief. So experience may be needed to acquire the relevant concepts in the example above, but once these concepts are possessed, no further experience providing empirical evidence is needed to know that the proposition is true, which is why it is considered to be justified a priori.

Empiricism and rationalism

In its strictest sense, empiricism is the view that all knowledge is based on experience or that all epistemic justification arises from empirical evidence. This stands in contrast to the rationalist view, which holds that some knowledge is independent of experience, either because it is innate or because it is justified by reason or rational reflection alone. Expressed through the distinction between knowledge a priori and a posteriori from the previous section, rationalism affirms that there is knowledge a priori, which is denied by empiricism in this strict form. One difficulty for empiricists is to account for the justification of knowledge pertaining to fields like mathematics and logic, for example, that 3 is a prime number or that modus ponens is a valid form of deduction. The difficulty is due to the fact that there seems to be no good candidate of empirical evidence that could justify these beliefs. Such cases have prompted empiricists to allow for certain forms of knowledge a priori, for example, concerning tautologies or relations between our concepts. These concessions preserve the spirit of empiricism insofar as the restriction to experience still applies to knowledge about the external world. In some fields, like metaphysics or ethics, the choice between empiricism and rationalism makes a difference not just for how a given claim is justified but for whether it is justified at all. This is best exemplified in metaphysics, where empiricists tend to take a skeptical position, thereby denying the existence of metaphysical knowledge, while rationalists seek justification for metaphysical claims in metaphysical intuitions.

Scientific evidence

Scientific evidence is closely related to empirical evidence. Some theorists, like Carlos Santana, have argued that there is a sense in which not all empirical evidence constitutes scientific evidence. One reason for this is that the standards or criteria that scientists apply to evidence exclude certain evidence that is legitimate in other contexts.[38] For example, anecdotal evidence from a friend about how to treat a certain disease constitutes empirical evidence that this treatment works but would not be considered scientific evidence.[38][39] Others have argued that the traditional empiricist definition of empirical evidence as perceptual evidence is too narrow for much of scientific practice, which uses evidence from various kinds of non-perceptual equipment.[40]

Central to scientific evidence is that it was arrived at by following scientific method in the context of some scientific theory.[41] But people rely on various forms of empirical evidence in their everyday lives that have not been obtained this way and therefore do not qualify as scientific evidence. One problem with non-scientific evidence is that it is less reliable, for example, due to cognitive biases like the anchoring effect,[42] in which information obtained earlier is given more weight, although science done poorly is also subject to such biases, as in the example of p-hacking.[38]

Observation, experimentation and scientific method

In the philosophy of science, it is sometimes held that there are two sources of empirical evidence: observation and experimentation.[43] The idea behind this distinction is that only experimentation involves manipulation or intervention: phenomena are actively created instead of being passively observed.[44][45][46] For example, inserting viral DNA into a bacterium is a form of experimentation while studying planetary orbits through a telescope belongs to mere observation.[47] In these cases, the mutated DNA was actively produced by the biologist while the planetary orbits are independent of the astronomer observing them. Applied to the history of science, it is sometimes held that ancient science is mainly observational while the emphasis on experimentation is only present in modern science and responsible for the scientific revolution.[44] This is sometimes phrased through the expression that modern science actively "puts questions to nature".[47] This distinction also underlies the categorization of sciences into experimental sciences, like physics, and observational sciences, like astronomy. While the distinction is relatively intuitive in paradigmatic cases, it has proven difficult to give a general definition of "intervention" applying to all cases, which is why it is sometimes outright rejected.[47][44]

Empirical evidence is required for a hypothesis to gain acceptance in the scientific community. Normally, this validation is achieved by the scientific method of forming a hypothesis, experimental design, peer review, reproduction of results, conference presentation, and journal publication. This requires rigorous communication of hypothesis (usually expressed in mathematics), experimental constraints and controls (expressed in terms of standard experimental apparatus), and a common understanding of measurement. In the scientific context, the term semi-empirical is used for qualifying theoretical methods that use, in part, basic axioms or postulated scientific laws and experimental results. Such methods are opposed to theoretical ab initio methods, which are purely deductive and based on first principles. Typical examples of both ab initio and semi-empirical methods can be found in computational chemistry.