| Dopamine agonist | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

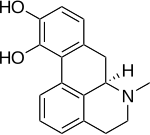

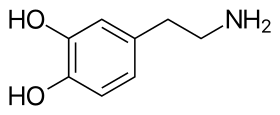

The skeletal structure of dopamine | |

| Class identifiers | |

| Use | Parkinson's disease, hyperprolactinemia, restless legs syndrome |

| ATC code | N04BC |

| Biological target | Dopamine receptors |

| External links | |

| MeSH | D010300 |

A dopamine agonist (DA) is a compound that activates dopamine receptors. There are two families of dopamine receptors, D2-like and D1-like, and they are all G protein-coupled receptors. D1- and D5-receptors belong to the D1-like family and the D2-like family includes D2, D3 and D4 receptors. Dopamine agonists are primarily used in the treatment of Parkinson's disease, and to a lesser extent, in hyperprolactinemia and restless legs syndrome. They are also used off-label in the treatment of clinical depression. The use of dopamine agonists is associated with impulse control disorders and dopamine agonist withdrawal syndrome (DAWS).

Medical uses

Parkinson's disease

Dopamine agonists are mainly used in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. The cause of Parkinson's is not fully known but genetic factors, for example specific genetic mutations, and environmental triggers have been linked to the disease. In Parkinson's disease dopaminergic neurons that produce the neurotransmitter dopamine in the brain slowly break down and can eventually die. With decreasing levels of dopamine the brain can't function properly and causes abnormal brain activity, which ultimately leads to the symptoms of Parkinson's disease.

There are two fundamental ways of treating Parkinson's disease, either by replacing dopamine or mimicking its effect.

Dopamine agonists act directly on the dopamine receptors and mimic dopamine's effect. Dopamine agonists have two subclasses: ergoline and non-ergoline agonists. Both subclasses target dopamine D2-type receptors. Types of ergoline agonists are cabergoline and bromocriptine and examples of non-ergoline agonists are pramipexole, ropinirole and rotigotine. Ergoline agonists are much less used nowadays because of the risk of cartilage formation in heart valves.

Treatment of depression in Parkinson's patients

Depressive symptoms and disorders are common in patients with Parkinson's disease and can affect their quality of life. Increased anxiety can accentuate the symptoms of Parkinson's and is therefore essential to treat. Instead of conventional antidepressant medication in treating depression, treatment with dopamine agonists has been suggested. It is mainly thought that dopamine agonists help with treating depressive symptoms and disorders by alleviating motor complications, which is one of the main symptoms of Parkinson's disease. Although preliminary evidence of clinical trials has shown interesting results, further research is crucial to establish the anti-depressive effects of dopamine agonists in treating depressive symptoms and disorders in those with Parkinson's.

Hyperprolactinemia

Dopamine is a prolactin-inhibiting factor (PIFs) since it lowers the prolactin-releasing factors (PRFs) synthesis and secretion through D2-like receptors. That is why dopamine agonists are the first-line treatment in hyperprolactinemia. Ergoline-derived agents, bromocriptine and cabergoline are mostly used in treatment. Research shows that these agents reduce the size of prolactinomas by suppressing the hypersecretion of prolactin resulting in normal gonadal function.

Restless leg syndrome

Numerous clinical trials have been performed to assess the use of dopamine agonists for the treatment of restless leg syndrome (RLS). RLS is identified by the strong urge to move and is a dopamine-dependent disorder. RLS symptoms decrease with the use of drugs that stimulate dopamine receptors and increase dopamine levels, such as dopamine agonists.

Adverse effects

Side effects

Dopamine agonists are mainly used to treat Parkinson’s disease but are also used to treat hyperprolactinemia and restless legs syndrome. The side effects are mainly recorded in treatment for Parkinson’s disease where dopamine agonists are commonly used, especially as first-line treatment with levodopa.

Dopamine agonists are divided into two subgroups or drug classes, first-generation and newer agents. Ergoline derived agonists are the first generation and are not used as much as the newer generation the non-ergoline derived agonists. Ergoline derived agonists are said to be "dirtier" drugs because of their interaction with other receptors than dopamine receptors, therefore they cause more side effects. Ergoline derived agonists are for example bromocriptine, cabergoline, pergolide and lisuride. Non-ergoline agonists are pramipexole, ropinirole, rotigotine, piribedil and apomorphine.

The most common adverse effects are constipation, nausea and headaches. Other serious side effects are hallucinations, peripheral edema, gastrointestinal ulcers, pulmonary fibrosis and psychosis.

Dopamine agonists have been linked to cardiac problems. Side effects such as hypotension, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, cardiac fibrosis, pericardial effusion and tachycardia. A high risk for valvular heart disease has been established in association with ergot-derived agonists especially in elderly patients with hypertension.

Somnolence and sleep attacks have been reported as an adverse effect that happen to almost 30% of patients using dopamine agonists. Daytime sleepiness, insomnia and other sleep disturbances have been reported as well.

Impulse control disorder that is described as gambling, hypersexuality, compulsive shopping and binge eating is one serious adverse effect of dopamine agonists.

After long-term use of dopamine agonist a withdrawal syndrome may occur when discontinuing or during dose reduction. The following side effects are possible: anxiety, panic attacks, dysphoria, depression, agitation, irritability, suicidal ideation, fatigue, orthostatic hypotension, nausea, vomiting, diaphoresis, generalised pain, and drug cravings. For some individuals, these withdrawal symptoms are short-lived and make a full recovery, for others a protracted withdrawal syndrome may occur with withdrawal symptoms persisting for months or years.

Interactions

Dopamine agonists interact with a number of drugs but there is little evidence that they interact with other Parkinson’s drugs. In most cases there is no reason not to co-administer Parkinson's drugs. Although there has been an indication that the use of dopamine agonists with L-DOPA can cause psychosis therefore it is recommended that either the use of dopamine agonists be discontinued or the dose of L-DOPA reduced. Since ergot-dopamine agonist have antihypertensive qualities it is wise to monitor blood pressure when using dopamine agonists with antihypertensive drugs to ensure that the patient does not get hypotension. That includes the drug sildenafil which is commonly used to treat erectile dysfunction but also used for pulmonary hypertension.

There is evidence that suggests that since ergot dopamine agonists are metabolized by CYP3A4 enzyme concentration rises with the use of CYP3A4 inhibitors. For example, in one study bromocriptine was given with a CYP3A4 inhibitor and the AUC (e. Area under the curve) increased 268%. Ropinirole is a non-ergot derived dopamine agonist and concomitant use with a CYP1A2 inhibitor can result in a higher concentration of ropinirole. When discontinuing the CYP1A2 inhibitor, if using both drugs, there is a change that a dose adjustment for ropinirole is needed. There is also evidence the dopamine agonists inhibit various CYP enzymes and therefore they may inhibit the metabolism of certain drugs.

Pharmacology

Ergoline class

Pharmacokinetics of Bromocriptine

The absorption of the oral dose is approximately 28% however, only 6% reaches the systemic circulation unchanged, due to a substantial first-pass effect. Bromocriptine reaches mean peak plasma levels in about 1–1.5 hours after a single oral dose. The drug has high protein binding, ranging from 90-96% bound to serum albumin. Bromocriptine is metabolized by CYP3A4 and excreted primarily in the feces via biliary secretion. Metabolites and parent drugs are mostly excreted via the liver, but also 6% via the kidney. It has a half-life of 2–8 hours.

Pharmacokinetics of Pergolide

Pergolide has a long half-life of about 27 hours and reaches a mean peak plasma level in about 2–3 hours after a single oral dose. The protein binding is 90% and the drug is mainly metabolized in the liver by CYP3A4 and CYP2D6. The major route of excretion is through the kidneys.

| Drug |

Maintenance |

Half-life |

Protein binding | Peak plasma | Metabolism | Excretion |

| Bromocriptine |

Oral, 2.5–40 mg/day

|

2–8 hours | 90-96% | 1-1,5 hours |

Hepatic, via CYP3A4, 93% first-pass metabolism

|

Bile, 94-98%

Renal, 2-6% |

| Pergolide |

Oral, 0.05 mg/day Usual response up to 0.1 mg per day

|

27 hours | 90% | 2–3 hours | Extensively hepatic | Renal, 50%

Fecal 50% |

Non-Ergoline class

Pharmacokinetics of Pramipexole

Pramipexole reaches maximum plasma concentration 1–3 hours post-dose. It is about 15% bound to plasma proteins and the metabolism is minimal. Pramipexole has a long half-life, around 27 hours. The drug is mostly excreted in the urine, around 90%, but also in feces.

Pharmacokinetics of Ropinirole

Ropinirole is rapidly absorbed after a single oral dose, reaching plasma concentration in approximately 1–2 hours. The half-life is around 5–6 hours. Ropinirole is heavily metabolized by the liver and in vitro studies show that the enzyme involved in the metabolism of ropinirole is CYP1A2.

Pharmacokinetics of Rotigotine

Since rotigotine is a transdermal patch it provides continuous drug delivery over 24 hours. It has a half-life of 3 hours and the protein binding is around 92% in vitro and 89.5% in vivo. Rotigotine is extensively and rapidly metabolized in the liver and by the CYP enzymes. The drug is mostly excreted in urine (71%), but also in feces (23%).

| Drug |

Maintenance |

Half-life |

Protein binding | Peak plasma | Metabolism | Excretion |

| Pramipexole |

Oral, 0.125 mg 3x/day (IR) Oral, 0.375 mg/day (ER)

|

8–12 hours | 15% | 1–3 hours | Minimal < 10% | Urine 90%

Fecal 2% |

| Ropinirole |

Oral, 0.25 mg 3x/day (IR) Oral, 2 mg/day (ER)

|

5–6 hours | 10-40% | 1–2 hours | Hepatic, via P450 CYP1A2 — can increase ↑ INR | Renal > 88% |

| Rotigotine |

Transdermal, 2 – 4 mg/day

|

3 hours |

92%

|

24 hours | Hepatic (CYP-mediated). | Urine 71%

Fecal 23% |

Mechanism of action

The dopamine receptors are 7-transmembrane domains and are members of the G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) superfamily. Dopamine receptors have five subtypes, D1 through D5, the subtypes can be divided into two subclasses due to their mechanism of action on adenylate cyclase enzyme, D1-like receptors (D1 and D5) and D2-like receptors (D2, D3 and D4). D1-like receptors are primarily coupled to Gαs/olf proteins and activates adenylate cyclase which increases intracellular levels of cAMP, they also activate the Gβγ complex and the N-type Ca2+ channel. D2-like receptors decrease intracellular levels of the second messenger cAMP by inhibiting adenylate cyclase.

Bromocriptine

Bromocriptine is an ergot derivative, semi-synthetic. Bromocriptine is a D2 receptor agonist and D1 receptor antagonist with a binding affinity to D2 receptors of anterior pituitary cells, exclusively on lactotrophs. Bromocriptine stimulates Na+, K+-ATPase activity and/or cytosolic Ca2+ elevation and therefore reduction of prolactin which leads to no production of cAMP.

Pramipexole

Pramipexole is a highly active non-ergot D2-like receptor agonist with a higher binding affinity to D3 receptors rather than D2 or D4 receptors. The mechanism of action of pramipexole is mostly unknown, it is thought to be involved in the activation of dopamine receptors in the area of the brain where the striatum and the substantia nigra is located. This stimulation of dopamine receptors in the striatum may lead to the better movement performance.

Structure–activity relationship

When dealing with agonists it can be extremely complex to confirm relationships between structure and biological activity. Agonists generate responses from living tissues. Therefore, their activity depends both on their efficacy to activate receptors and their affinity to bind to receptors.

Crossing the blood brain barrier

Many molecules are unable to cross the blood brain barrier (BBB). Molecules must be small, non-polar and lipophilic to cross over. If compounds do not possess these qualities they must have a specific transporter that can transport them over the BBB. Dopamine cannot diffuse across the BBB because of the catechol group, it is too polar and therefore unable to enter the brain. The catechol group is a dihydroxy benzene ring.

The synthesis of dopamine consists of three stages. The synthesis process starts with an amino acid, called L-Tyrosine. In the second stage Levodopa (L-dopa) is formed by adding a phenol group to the benzene ring of L-Tyrosine. The formation of L-dopa from L-tyrosine is catalyzed by the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase. The third stage is the formation of dopamine by removing the carboxylic acid group from L-dopa, catalysed by the enzyme dopa decarboxylase.

Levodopa is also too polar to cross the blood brain barrier but it happens to be an amino acid so it has a specialized transporter called L-type amino acid transporter or LAT-1 that helps it diffuse through the barrier.

Dopamine

When dopamine interacts with ATP, which is a component of some dopamine receptors, it has a significant preference for a trans-conformation of the dopamine molecule. The dopamine-ATP complex is stabilised by hydrogen bonding between catechol hydroxyls and purine nitrogens and by electrostatic interactions between the protonated ammonium group of dopamine and a negative phosphate group. Two conformers of dopamine have been identified as alpha- and beta-conformers in which the catechol ring is coplanar with the plane of the ethylamine side chain. They are substantial in agonist-receptor interactions.

Ergoline derivatives

Central dopaminergic agonist properties of semisynthetic ergoline derivatives lergotrile, pergolide, bromocriptine and lisuride have been established. Some studies suggest that ergot alkaloids have the properties of mixed agonist-antagonist with regards to certain presynaptic and postsynaptic receptors. N-n-Propyl groups (chemical formula: –CH2CH2CH3) frequently enhance dopamine agonist effects in the ergoline derivatives.

The (+)-enantiomer displays notably diminished activity whereas the (-)-enantiomer possess potent dopamine agonist properties.

Bromocriptine

Bromocriptine has an ergot alkaloid structure. Ergot alkaloids are divided into 2 groups; amino acid ergot alkaloids and amine ergot alkaloids, bromocriptine is part of the former group. It contains a bromine halogen on the ergot structure which increases the affinity for the D2-receptor but often reduces the efficacy. The similarity between the dopamine structure and the ergoline ring in bromocriptine is likely the cause for its action on the dopamine receptors. It has shown to have equal affinity for D2- and D3-receptor and much lower affinity for D1-receptor.

Non-ergoline derivatives

Non-ergoline dopamine receptor agonists have higher binding affinity to dopamine D3-receptors than dopamine D2-receptors. This binding affinity is related to D2 and D3 receptor homology, the homology between them has a high degree of sequence and is closest in their transmembrane domains, were they share around 75% of the amino acid.

Apomorphine

Apomorphine has a catechol element and belongs to a class called β-phenylethylamines and its main components are similar to the dopamine structure. The effect that apomorphine has on the dopamine receptors can also be linked to the similarities between its structure and dopamine. It is a chiral molecule and thus can be acquired in both the R and S form, the R form is the one that is used in therapy. When apomorphine interacts with the dopamine receptor, or the ATP on the receptor, the catechol and nitrogen are important to stabilize the structure with hydrogen bonding. The position of the hydroxyl groups is also important and monohydroxy derivatives have been found to be less potent than the dihydroxy groups. There are a number of stability concerns with apomorphine such as oxidation and racemization.

Rotigotine

Rotigotine is a phenolic amine and thus has poor oral bioavailability and fast clearance from the body. Therefore, it has been formulated as a transdermal patch, first and foremost to prevent first pass metabolism in the liver.

Members

Examples of dopamine agonists include:

Partial agonist

- Aripiprazole (Partial agonist of the D2 family receptors - Trade name "Abilify" in the United States; atypical antipsychotic)

- Phencyclidine (a.k.a. PCP; partial agonist. Psychoactivity mainly due to NMDA antagonism)

- Quinpirole (Partial agonist of the D2 and D3 family of receptors)

- Salvinorin A (chief active constituent of the psychedelic herb salvia divinorum, the psychoactivity of which is mainly due to Kappa-opioid receptor agonism; partial agonist at the D2 with an Intrinsic activity of 40-60%, binding affinity of Ki=5-10nM and EC50=50-90nM)

Agonists of full/unknown efficacy

- Apomorphine (Apokyn – used to treat Parkinson's disease & Restless leg syndrome ) – biased at the D1 receptor.

- Bromocriptine (Parlodel – used to treat PD/RLS)

- Cabergoline (Dostinex – used to treat PD/RLS)

- Ciladopa (used to treat PD/RLS)

- Dihydrexidine (used to treat PD/RLS)

- Dinapsoline (used to treat PD/RLS)

- Doxanthrine (used to treat PD/RLS)

- Epicriptine (used to treat PD/RLS)

- Lisuride (used to treat PD/RLS)

- Pergolide (used to treat PD/RLS) – previously available as Permax, but removed from the market in the USA on March 29, 2007.

- Piribedil (Pronoran and Trivastal – used to treat PD/RLS)

- Pramipexole (Mirapex and Sifrol – used to treat PD/RLS)

- Propylnorapomorphine (used to treat PD/RLS)

- Quinagolide (Norprolac – used to treat PD/RLS)

- Ropinirole (Requip – used to treat PD/RLS)

- Rotigotine (Neupro – used to treat PD/RLS)

- Roxindole (used to treat PD/RLS)

- Sumanirole (used to treat PD/RLS)

Some, such as fenoldopam, are selective for dopamine receptor D1.

Related class of drugs: Indirect agonists

There are two classes of drugs that act as indirect agonists of dopamine receptors: dopamine reuptake inhibitors and dopamine releasing agents. These are not considered dopamine agonists, since they have no specific agonist activity at dopamine receptors, but they are nonetheless related. Indirect agonists are prescribed for a wider range of conditions than standard dopamine agonists.

The most commonly prescribed indirect agonists of dopamine receptors include:

- Amphetamine and/or dextroamphetamine (used to treat ADHD, narcolepsy, and obesity)

- Bupropion (used to facilitate smoking cessation and treat nicotine addiction and clinical depression)

- Lisdexamfetamine (used to treat ADHD and binge eating disorder)

- Methylphenidate or dexmethylphenidate (used to treat ADHD and narcolepsy)

Other examples include:

- Cathinone

- Cocaine (anesthetic with no medical uses as a central nervous system stimulant)

- Methamphetamine (used in rare circumstances to treat ADHD and obesity)

- Phenethylamine (endogenous trace amine)

- p-Tyramine (endogenous trace amine)

History

Since the late 1960 Levodopa (L-DOPA) has been used to treat Parkinson’s disease but there has always been a debate whether the treatment is worth the side effects. Around 1970 clinicians started using the dopamine agonist apomorphine alongside L-DOPA to minimize the side effects caused by L-DOPA, the dopamine agonists bind to the dopamine receptor in the absence of dopamine. Apomorphine had limited use since it had considerable side effects and difficulty with administration. In 1974 bromocriptine was use widely after clinicians discovered its benefits in treating Parkinsons. When using the two drug classes together there is a possibility to reduce the amount of L-DOPA by 20-30% and thus keeping the fluctuating motor responses to a minimum. Dopamine agonists are often used in younger people as monotherapy and as initial therapy instead of L-DOPA. Although it is important to know that there is a correlation between the two drugs, if l-DOPA doesn't work dopamine agonists are also ineffective.

The early dopamine agonists, such as bromocriptine, were ergot derived and activated the D2-receptor. They induced major side effects such as fibrosis of cardiac valves. It is considered that the reason they induced such side effects is that they activate many types of receptors.

Because of the major adverse effects of ergot derived dopamine agonists they are generally not used anymore and were mostly abandoned in favor of non-ergot agonists such as pramipexole, ropinirole and rotigotine. They do not induce as serious side effects although common side effects are nausea, edema and hypotension. Patients have also shown impaired impulse control such as overspending, hypersexuality and gambling.