From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Self-conceptIn the psychology of self, one's self-concept (also called self-construction, self-identity, self-perspective or self-structure) is a collection of beliefs about oneself. Generally, self-concept embodies the answer to the question "Who am I?".

The self-concept is distinguishable from self-awareness, which is the extent to which self-knowledge is defined, consistent, and currently applicable to one's attitudes and dispositions. Self-concept also differs from self-esteem:

self-concept is a cognitive or descriptive component of one's self

(e.g. "I am a fast runner"), while self-esteem is evaluative and

opinionated (e.g. "I feel good about being a fast runner").

Self-concept is made up of one's self-schemas,

and interacts with self-esteem, self-knowledge, and the social self to

form the self as a whole. It includes the past, present, and future

selves, where future selves (or possible selves) represent individuals'

ideas of what they might become, what they would like to become, or what

they are afraid of becoming. Possible selves may function as incentives

for certain behaviour.

The perception people have about their past or future selves

relates to their perception of their current selves. The temporal

self-appraisal theory

argues that people have a tendency to maintain a positive

self-evaluation by distancing themselves from their negative self and

paying more attention to their positive one. In addition, people have a

tendency to perceive the past self less favourably (e.g. "I'm better than I used to be") and the future self more positively (e.g. "I will be better than I am now").

History

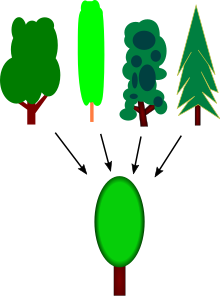

Psychologists Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow

had major influence in popularizing the idea of self-concept in the

west. According to Rogers, everyone strives to reach an "ideal self." He

believed that a person gets to self-actualize when they prove to

themself that they are capable enough to achieve their goals and

desires, but in order to attain their fullest potential, the person must

have been raised in healthy surroundings which consist of "genuineness,

acceptance, and empathy", however, the lack of relationships with

people that have healthy personalities will stop the person from growing

"like a tree without sunlight and water" and affect the individual's

process to accomplish self- actualization.

Rogers also hypothesized that psychologically healthy people actively

move away from roles created by others' expectations, and instead look

within themselves for validation. On the other hand, neurotic

people have "self-concepts that do not match their experiences. They

are afraid to accept their own experiences as valid, so they distort

them, either to protect themselves or to win approval from others."

According to Carl Rogers, the self-concept has three different components:

Abraham Maslow applied his concept of self-actualization in his

hierarchy of needs theory. In this theory, he explained the process it

takes for a person to achieve self-actualization. He argues that for an

individual to get to the "higher level growth needs", he must first

accomplish "lower deficit needs". Once the "deficiency needs" have been

achieved, the person's goal is to accomplish the next step, which is the

"being needs". Maslow noticed that once individuals reach this level,

they tend to "grow as a person" and reach self-actualization. However,

individuals who experienced negative events while being in the lower

deficit needs level prevents them from ascending in the hierarchy of

needs.

The self-categorization theory developed by John Turner

states that the self-concept consists of at least two "levels": a

personal identity and a social one. In other words, one's

self-evaluation relies on self-perceptions and how others perceive them.

Self-concept can alternate rapidly between one's personal and social

identity.

Children and adolescents begin integrating social identity into their

own self-concept in elementary school by assessing their position among

peers.

By age five, acceptance from peers significantly affects children's

self-concept, affecting their behaviour and academic success.

Model

One's self-perception is defined by one's self-concept, self-knowledge, self-esteem, and social self.

The self-concept is an internal model that uses self-assessments in order to define one's self-schemas. Changes in self-concept can be measured by spontaneous self-report where a person is prompted by a question like "Who are you?". Often when measuring changes to the self self-evaluation, whether a person has a positive or negative opinion of oneself, is measured instead of self-concept.

Features such as personality, skills and abilities, occupation and hobbies, physical characteristics, gender,

etc. are assessed and applied to self-schemas, which are ideas of

oneself in a particular dimension (e.g., someone that considers

themselves a geek

will associate "geek-like" qualities to themselves). A collection of

self-schemas makes up one's overall self-concept. For example, the

statement "I am lazy" is a self-assessment that contributes to

self-concept. Statements such as "I am tired", however, would not be

part of someone's self-concept, since being tired is a temporary state

and therefore cannot become a part of a self-schema. A person's

self-concept may change with time as reassessment occurs, which in

extreme cases can lead to identity crises.

Parts

Various theories identify different parts of the self include:

Development

Researchers debate over when self-concept development begins. Some assert that gender stereotypes and expectations set by parents for their children affect children's understanding of themselves by approximately age three.

However, at this developmental stage, children have a very broad sense

of self; typically, they use words such as big or nice to describe

themselves to others.

While this represents the beginnings of self-concept, others suggest

that self-concept develops later, in middle childhood, alongside the

development of self-control.

At this point, children are developmentally prepared to interpret their

own feelings and abilities, as well as receive and consider feedback

from peers, teachers, and family.

In adolescence, the self-concept undergoes a significant time of

change. Generally, self-concept changes more gradually, and instead,

existing concepts are refined and solidified.

However, the development of self-concept during adolescence shows a

"U"-shaped curve, in which general self-concept decreases in early

adolescence, followed by an increase in later adolescence.

Romantic relationships can affect people's self-concept throughout a relationship. Self-expansion describes the addition of information to an individual's concept of self.

Self-expansion can occur during relationships. Expansion of

self-concept can occur during relationships, during new challenging

experiences.

Additionally, teens begin to evaluate their abilities on a

continuum, as opposed to the "yes/no" evaluation of children. For

example, while children might evaluate themselves "smart", teens might

evaluate themselves as "not the smartest, but smarter than average."

Despite differing opinions about the onset of self-concept development,

researchers agree on the importance of one's self-concept, which

influences people's behaviors and cognitive and emotional outcomes

including (but not limited to) academic achievement, levels of happiness, anxiety, social integration, self-esteem, and life-satisfaction.

Academic

Academic self-concept refers to the personal beliefs about their academic abilities or skills. Some research suggests that it begins developing from ages three to five due to influence from parents and early educators. By age ten or eleven, children assess their academic abilities by comparing themselves to their peers. These social comparisons are also referred to as self-estimates. Self-estimates of cognitive ability are most accurate when evaluating subjects that deal with numbers, such as math. Self-estimates were more likely to be poor in other areas, such as reasoning speed.

Some researchers suggest that to raise academic self-concept,

parents and teachers need to provide children with specific feedback

that focuses on their particular skills or abilities.

Others also state that learning opportunities should be conducted in

groups (both mixed-ability and like-ability) that downplay social

comparison, as too much of either type of grouping can have adverse

effects on children's academic self-concept and the way they view

themselves in relation to their peers.

Physical

Physical

self-concept is the individual's perception of themselves in areas of

physical ability and appearance. Physical ability includes concepts such

as physical strength and endurance, while appearance refers to

attractiveness and body image.

Adolescents experience significant changes in general physical

self-concept at the onset of puberty, about eleven years old for girls

and about 15 years old for boys. The bodily changes during puberty, in

conjunction with the various psychological of this period, makes

adolescence especially significant for the development of physical

self-concept.

An important factor of physical self-concept development is

participation in physical activities. It has even been suggested that

adolescent involvement in competitive sports increases physical

self-concept.

Gender identity

A person's gender identity is a sense of one's own gender. These ideas typically form in young children.

According to the International Encyclopedia of Marriage and Family,

gender identity is developed at an early age when the child starts to

communicate; by the age of eighteen months to two years is when the

child begins to identify as a girl or a boy.

After this stage, some consider gender identity already formed,

although some consider non-gendered identities more salient during that

young of an age. Kohlberg noted gender constancy occurs by the ages of

five to six, a child becomes well-aware of their gender identity.

Both biological and social factors may influence identities such as a

sense of individuality, identities of place as well as gendered

identities. As part of environmental attitudes, some suggest women more

than men care about the environment.

Forms of gender stereotyping is also important to consider in clinical

settings. For example, a study at Kuwait University with a small sample

of 102 men with gender dysphoria examined self-concept, masculinity and femininity. Findings were that children who grew up on lower family bonds had lower self-concept.

Clearly, it is important to consider the context of social and

political attitudes and beliefs before drawing any conclusions about

gender identities in relation to personality, particularly about mental

health and issues around acceptable behaviours.

Measures

Motivational properties

Self-concept

can have motivational properties. There are four types of motives in

particular that are most related to self-concept:

- Self-assessment: desire to receive information about the self that is accurate

- Self-enhancement: desire to receive feedback that informs the self of positive or desirable characteristics

- Self-verification: desire to confirm what one already knows about the self

- Self-improvement: desire to learn things that will help to improve the self

Some of these motives may be more prominent depending on the

situation. In Western societies, the most automatic is the

self-enhancement motive, and may be dominant in some situations where

motives contradict one another.

For example, the self-enhancement motive may contradict and dominate

the self-assessment motive if one seeks out inaccurate compliments

rather than honest feedback. Additionally, self-concept can motivate

behavior because people tend to act in ways that reaffirm their

self-concept,

which is consistent with the idea of the self-verification motive. In

particular, if people perceive the self a certain way and receive

feedback contrary to this perception, a tension is produced that

motivates them to reestablish consistency between environmental feedback

and self-concept.

For example, if someone believes herself to be outgoing, but someone

tells her she is shy, she may be motivated to avoid that person or the

environment in which she met that person because it is inconsistent with

her self-concept of being an outgoing person. Further, another major

motivational property of self-concept comes from the desire to eliminate

the discrepancy between one's current self-concept and his or her ideal

possible self.

This is parallel with the idea of the self-improvement motive. For

example, if one's current self-concept is that she is a novice at piano

playing, though she wants to become a concert pianist, this discrepancy

will generate motivation to engage in behaviors (like practicing playing

piano) that will bring her closer to her ideal possible self (being a

concert pianist).

Cultural differences

Worldviews about one's self in relation to others differ across and within cultures. Western cultures place particular importance on personal independence and on the expression of one's own attributes

(i.e. the self is more important than the group). This is not to say

those in an independent culture do not identify and support their

society or culture, there is simply a different type of relationship. Non-Western cultures favor an interdependent view of the self:

Interpersonal relationships are more important than one's individual

accomplishments, and individuals experience a sense of oneness with the

group. Such identity fusion can have positive and negative consequences.

Identity fusion can give people the sense that their existence is

meaningful provided the person feels included within the society (for

example, in Japan, the definition of the word for self (jibun) roughly translates to "one's share of the shared life space").

Identity fusion can also harm one's self-concept because one's

behaviors and thoughts must be able to change to continue to align with

those of the overall group. Non-interdependent self-concepts can also differ between cultural traditions.

Additionally, one's social norms and cultural identities have a large effect on self-concept and mental well-being. When a person can clearly define their culture's norms and how those play a part in their life, that person is more likely to have a positive self-identity, leading to better self-concept and psychological welfare.

One example of this is in regards to consistency. One of the social

norms within a Western, independent culture is consistency, which allows

each person to maintain their self-concept over time. The social norm in a non-Western, interdependent culture has a larger focus on one's ability to be flexible and to change as the group and environment change.

If this social norm is not followed in either culture, this can lead to

a disconnection with one's social identity, which affects personality,

behavior, and overall self-concept. Buddhists emphasize the impermanence of any self-concept.

Anit Somech, an organizational psychologist and professor, who

carried a small study in Israel showed that the divide between

independent and interdependent self-concepts exists within cultures as well. Researchers compared mid-level merchants in an urban community with those in a kibbutz (collective community).

The managers from the urban community followed the independent culture.

When asked to describe themselves, they primarily used descriptions of

their own personal traits without comparison to others within their

group.

When the independent, urban managers gave interdependent-type

responses, most were focused on work or school, due to these being the

two biggest groups identified within an independent culture. The kibbutz managers followed the interdependent culture. They used hobbies and preferences

to describe their traits, which is more frequently seen in

interdependent cultures as these serve as a means of comparison with

others in their society. There was also a large focus on residence,

lending to the fact they share resources and living space with the

others from the kibbutz. These types of differences were also seen in a

study done with Swedish and Japanese adolescents. Typically, these would both be considered

non-Western cultures, but the Swedish showed more independent traits,

while the Japanese followed the expected interdependent traits.

Along with viewing one's identity as part of a group, another factor that coincides with self-concept is stereotype threat. Many working names have been used for this term: stigmatization, stigma pressure, stigma vulnerability and stereotype vulnerability.

The terminology that was settled upon Claude Steele and Joshua Aronson

to describe this "situational predicament was 'stereotype threat.' This

term captures the idea of a situational predicament as a contingency of

their [marginalized] group identity, a real threat of judgment or

treatment in the person's environment that went beyond any limitations

within." Steele

and Aronson described the idea of stereotype threat in their study of

how this socio‐psychological notion affected the intellectual

performance of African Americans.

Steele and Aronson tested a hypothesis by administering a diagnostic

exam between two different groups: African American and White students.

For one group a stereotype threat was introduced while the other served

as a control. The findings were that academic performance of the African

American students was significantly lower than their White counterparts

when a stereotype threat was perceived after controlling for

intellectual ability. Since the inception by Steele and Aronson of

stereotype threat, other research has demonstrated the applicability of

this idea to other groups.

When one's actions could negatively influence general assumptions

of a stereotype, those actions are consciously emphasized. Instead of

one's individual characteristics, one's categorization into a social

group is what society views objectively - which could be perceived as a

negative stereotype, thus creating a threat. "The notion that

stereotypes held about a particular group may create psychologically

threatening situations associated with fears of confirming judgment

about one's group, and in turn, inhibit learning and performance."

The presence of stereotype threat perpetuates a "hidden curriculum"

that further marginalized minority groups. Hidden curriculum refers to a

covert expression of prejudice where one standard is accepted as the

"set and right way to do things". More specifically, the hidden

curriculum is an unintended transmission of social constructs that

operate in the social environment of an educational setting or

classroom. In the United States' educational system, this caters to dominant culture groups in American society.

"A primary source of stereotyping is often the teachers education

program itself. It is in these programs that teachers learn that poor

students and students of color should be expected to achieve less than

their 'mainstream' counterparts."

These child-deficit assumptions that are built into the program that

instructs teachers and lead to inadvertently testing all students on a

"mainstream" standard that is not necessarily academic and that does not

account for the social values and norms of non-"mainstream" students.

For example, the model of "teacher as the formal authority" is the orthodox teaching role that has been perpetuated

for many years until the 21st-century teaching model landed on the

scene. As part of the 5 main teaching style proposed by Anthony Grasha, a

cognitive and social psychologist until his death in 2003, the

authoritarian style is described as believing that there are "correct,

acceptable, and standard ways to do things".

Gender issues

Some

say, girls tend to prefer one-on-one (dyadic) interaction, forming

tight, intimate bonds, while boys prefer group activities.

One study in particular found that boys performed almost twice as well

in groups than in pairs, whereas girls did not show such a difference.

In early adolescence, the variations in physical self-concepts appear

slightly stronger for boys than girls. This includes self-concepts about

movement, body, appearance and other physical attributes. Yet during

periods of physical change such as infancy, adolescence and ageing, it

is particularly useful to compare these self-concepts with measured

skills before drawing broad conclusions.

Some studies suggest self-concept of social behaviours are

substantially similar with specific variations for girls and boys. For

instance, girls are more likely than boys to wait their turn to speak,

agree with others, and acknowledge the contributions of others. It seems

boys see themselves as building larger group relationships based on

shared interests, threaten, boast, and call names.

In mixed-sex pairs of children aged 33 months, girls were more likely

to passively watch a boy play, and boys were more likely to be

unresponsive to what the girls were saying.

In some cultures, such stereotypical traits are sustained from

childhood to adulthood suggesting a strong influence of expectations by

other people in these cultures.

The key impacts of social self-concepts on social behaviours and of

social behaviours on social self-concepts is a vital area of ongoing

research.

In contrast, research suggest overall similarities for gender

groups in self-concepts about academic work. In general, any variations

are systematically gender-based yet small in terms of effect sizes. Any

variations suggest overall academic self-concept are slightly stronger

for men than women in mathematics, science and technology and slightly

stronger for women than men about language related skills. It is

important to observe there is no link between self concepts and skills

[i.e., correlations about r = 0.19 are rather weak if statistically

significant with large samples]. Clearly, even small variations in

perceived self-concepts tend to reflect gender stereotypes evident in

some cultures .

In recent years, more women have been entering into the STEM field,

working in predominantly mathematics, technology and science related

careers. Many factors play a role in variations in gender effects on

self-concept to accumulate as attitudes to mathematics and science; in

particular, the impact other people's expectations rather than

role-models on our self-concepts .

Media

A commonly-asked question is "why do people choose one form of media over another?" According to the Galileo Model, there are different forms of media spread throughout three-dimensional space.

The closer one form of media is to another the more similar the source

of media is to each other. The farther away from each form of media is

in space, the least similar the source of media is. For example, mobile

and cell phone are located closest in space where as newspaper and

texting are farthest apart in space. The study further explained the

relationship between self-concept and the use of different forms of

media. The more hours per day an individual uses a form of media, the

closer that form of media is to their self-concept.

Self-concept is related to the form of media most used.

If one considers oneself tech savvy, then one will use mobile phones

more often than one would use a newspaper. If one considers oneself old

fashioned, then one will use a magazine more often than one would

instant message.

In this day and age, social media is where people experience most

of their communication. With developing a sense of self on a

psychological level, feeling as part of a greater body such as social,

emotional, political bodies can affect how one feels about themselves. If a person is included or excluded from a group, that can affect how they form their identities.

Growing social media is a place for not only expressing an already

formed identity, but to explore and experiment with developing

identities. In the United Kingdom, a study about changing identities

revealed that some people believe that partaking in online social media

is the first time they have felt like themselves, and they have achieved

their true identities. They also revealed that these online identities

transferred to their offline identities.

A 2007 study was done on adolescents aged 12 to 18 to view the

ways in which social media affects the formation of an identity. The

study found that it affected the formation in three different ways: risk

taking, communication of personal views, and perceptions of influences.

In this particular study, risk taking behavior was engaging with

strangers. When it came to communication about personal views, half of

the participants reported that it was easier to express these opinions

online, because they felt an enhanced ability to be creative and

meaningful. When it came to other's opinions, one subject reported

finding out more about themselves, like openness to experience, because

of receiving differing opinions on things such as relationships.