From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mating_system

A mating system is a way in which a group is structured in relation to sexual behaviour. The precise meaning depends upon the context. With respect to animals, the term describes which males and females mate under which circumstances. Recognised systems include monogamy, polygamy (which includes polygyny, polyandry, and polygynandry), and promiscuity, all of which lead to different mate choice outcomes and thus these systems affect how sexual selection works in the species which practice them. In plants, the term refers to the degree and circumstances of outcrossing. In human sociobiology, the terms have been extended to encompass the formation of relationships such as marriage.

In plants

The primary mating systems in plants are outcrossing (cross-fertilisation), autogamy (self-fertilisation) and apomixis (asexual reproduction without fertilization, but only when arising by modification of sexual function). Mixed mating systems, in which plants use two or even all three mating systems, are not uncommon.

A number of models have been used to describe the parameters of plant mating systems. The basic model is the mixed mating model, which is based on the assumption that every fertilisation is either self-fertilisation or completely random cross-fertilisation. More complex models relax this assumption; for example, the effective selfing model recognises that mating may be more common between pairs of closely related plants than between pairs of distantly related plants.

In animals

The following are some of the mating systems generally recognized in animals:

- Monogamy: One male and one female have an exclusive mating relationship. The term "pair bonding" often implies this. This is associated with one-male, one-female group compositions. There are two types of monogamy: type 1, which is facultative, and type 2, which is obligate. Facultative monogamy occurs when there are very low densities in a species. This means that mating occurs with only a single member of the opposite sex because males and females are very far apart. When a female needs aid from conspecifics in order to have a litter this is obligate monogamy. However, with this, the habitat carrying capacity is small so it means only one female can breed within the habitat.

- Polygamy: Three types are recognized:

- Polygyny (the most common polygamous mating system in vertebrates so far studied): One male has an exclusive relationship with two or more females. This is associated with one-male, multi-female group compositions. Many perennial Vespula squamosa (southern yellowjacket) colonies are polygynous. Different types of polygyny exist, such as lek polygyny and resource defense polygyny. Grayling butterflies (Hipparchia semele) engage in resource defense polygyny, where females choose a territorial male based on the best oviposition site. Although most animals opt for only one of these strategies, some exhibit hybrid strategies, such as the bee species, Xylocopa micans.

- Polyandry: One female has an exclusive relationship with two or more males. This is very rare and is associated with multi-male, multi-female group compositions. Genetic polyandry is found some insect species such as Apis mellifera (the Western Honey Bee), in which a virgin queen will mate with multiple drones during her nuptial flight whereas each drone will die immediately upon mating once. The queen will then store the sperm collected from these multiple matings in her spermatheca to use to fertilize eggs throughout the course of her entire reproductive life.

- Polygynandry: Polygynandry is a slight variation of this, where two or more males have an exclusive relationship with two or more females; the numbers of males and females do not have to be equal, and in vertebrate species studied so far, the number of males is usually less. This is associated with multi-male, multi-female group compositions.

- Promiscuity: A member of one sex within the social group mates with any member of the opposite sex. This is associated with multi-male, multi-female group compositions.

These mating relationships may or may not be associated with social relationships, in which the sexual partners stay together to become parenting partners. As the alternative term "pair bonding" implies, this is usual in monogamy. In many polyandrous systems, the males and the female stay together to rear the young. In polygynous systems where the number of females paired with each male is low and the male will often stay with one female to help rear the young, while the other females rear their young on their own. In polygynandry, each of the males may assist one female; if all adults help rear all the young, the system is more usually called "communal breeding". In highly polygynous systems, and in promiscuous systems, paternal care of young is rare, or there may be no parental care at all.

These descriptions are idealized, and the social partnerships are often easier to observe than the mating relationships. In particular:

- the relationships are rarely exclusive for all individuals in a species. DNA fingerprinting studies have shown that even in pair-bonding, matings outside the pair (extra-pair copulations) occur with fair frequency, and a significant minority of offspring result from them. However, the offspring that are a result of extra-pair copulations usually exhibit more advantageous genes. These genes can be associated with improvements in appearance, mating, and the functioning of internal body systems.

- some species show different mating systems in different circumstances, for example in different parts of their geographical range, or under different conditions of food availability

- mixtures of the simple systems described above may occur.

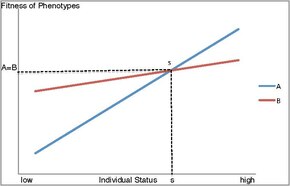

Sexual conflict occurs between individuals of different sexes that have separate or conflicting requirements for optimal mating success. This conflict may lead to competitive adaptations and co-adaptations of one or both of the sexes to maintain mating processes that are beneficial to that sex. Intralocus sexual conflict and interlocus sexual conflict describe the genetic influence behind sexual conflict, and are presently recognized as the most basic forms of sexual conflict.

In humans

Compared to other vertebrates, where a species usually has a single mating system, humans display great variety. Humans also differ by having formal marriages which in some cultures involve negotiation and arrangement between elder relatives. Regarding sexual dimorphism (see the section about animals above), humans are in the intermediate group with moderate sex differences in body size but with relatively large testes, indicating relatively frequent sperm competition in socially monogamous and polygynous human societies. One estimate is that 83% of human societies are polygynous, 0.05% are polyandrous, and the rest are monogamous. Even the last group may at least in part be genetically polygynous.

From an evolutionary standpoint, females are more prone to practice monogamy because their reproductive success is based on the resources they are able to acquire through reproduction rather than the quantity of offspring they produce. However, males are more likely to practice polygamy because their reproductive success is based on the amount of offspring they produce, rather than any kind of benefit from parental investment.

Polygyny is associated with an increased sharing of subsistence provided by women. This is consistent with the theory that if women raise the children alone, men can concentrate on the mating effort. Polygyny is also associated with greater environmental variability in the form of variability of rainfall. This may increase the differences in the resources available to men. An important association is that polygyny is associated with a higher pathogen load in an area which may make having good genes in a male increasingly important. A high pathogen load also decreases the relative importance of sororal polygyny which may be because it becomes increasingly important to have genetic variability in the offspring (See Major histocompatibility complex and sexual selection).

Virtually all the terms used to describe animal mating systems were adopted from social anthropology, where they had been devised to describe systems of marriage. This shows that human sexual behavior is unusually flexible since, in most animal species, one mating system dominates. While there are close analogies between animal mating systems and human marriage institutions, these analogies should not be pressed too far, because in human societies, marriages typically have to be recognized by the entire social group in some way, and there is no equivalent process in animal societies. The temptation to draw conclusions about what is "natural" for human sexual behavior from observations of animal mating systems should be resisted: a socio-biologist observing the kinds of behavior shown by humans in any other species would conclude that all known mating systems were natural for that species, depending on the circumstances or on individual differences.

As culture increasingly affects human mating choices, ascertaining what is the 'natural' mating system of the human animal from a zoological perspective becomes increasingly difficult. Some clues can be taken from human anatomy, which is essentially unchanged from the prehistoric past:

- humans have a large relative size of testes to body mass in comparison to most primates;

- humans have a large ejaculate volume and sperm count in comparison to other primates;

- as compared to most primates, humans spend more time in copulation;

- as compared to most primates, humans copulate with greater frequency;

- the outward signs of estrus in women (i.e. higher body temperature, breast swelling, sugar cravings, etc.), are often perceived to be less obvious in comparison to the outward signs of ovulation in most other mammals;

- for most mammals, the estrous cycle and its outward signs bring on mating activity; the majority of female-initiated matings in humans coincides with estrus, but humans copulate throughout the reproductive cycle;

- after ejaculation/orgasm in males and females, humans release a hormone that has a sedative effect;

Some have suggested that these anatomical factors signify some degree of sperm competition, though as levels of genetic and societal promiscuity are highly varied across cultures, this evidence is far from conclusive.

Genetic causes and effects

Monogamy has evolved multiple times in animals, with homologous brain structures predicting the mating and parental strategies used by them. These homologous structures were brought about by similar mechanisms. Even though there have been many different evolutionary pathways to get to monogamy, all the studied organisms express their genes very similarly in the fore and midbrain, implying a universal mechanism for the evolution of monogamy in vertebrates. While genetics is not the exclusive cause of mating systems within animals, it is influential in many animals, particularly rodents, which have been the most heavily researched. Certain rodents’ mating systems—monogamous, polygynous, or socially monogamous with frequent promiscuity—are correlated with suggested evolutionary phylogenies, where rodents more closely related genetically are more likely to use a similar mating system, suggesting an evolutionary basis. These differences in mating strategy can be traced back to a few significant alleles that affect behaviors that are heavily influential on mating system, such as the alleles responsible for the level of parental care, how animals choose their partner(s), and sexual competitiveness, among others, which are all at least partially influenced by genetics. While these genes may not perfectly correlate with the mating system that animals use, genetics is one factor that may lead to a species or population reproducing using one mating system over another, or even potentially multiple at different locations or points in time.

Mating systems can also have large impacts on the genetics of a population, strongly affecting natural selection and speciation. In plover populations, polygamous species tend to speciate more slowly than monogamous species do. This is likely because polygamous animals tend to move larger distances to find mates, contributing to a high level of gene flow, which can genetically homogenize many nearby subpopulations. Monogamous animals, on the other hand, tend to stay closer to their starting location, not dispersing as much. Because monogamous animals don’t migrate as far, monogamous populations which are geographically closer together tend to reproductively isolate from each other more easily, and thus each subpopulation is more likely to diversify or speciate from the other nearby populations as compared to polygamous populations. In polygamous species, however, the male partner in polygynous species and female partner in polyandrous species often tend to spread further to look for mates, potentially to find more or better mates. The increased level of movement among populations leads to increased gene flow between populations, effectively making geographically distinct populations into genetically similar ones via interbreeding. This has been observed in some species of rodents, where generally promiscuous species were quickly differentiated into monogamous and polygamous taxa by a prominent introduction of monogamous behaviors in some populations of that species, showing the swift evolutionary effects different mating systems can have. Specifically, monogamous populations speciated up to 4.8 times faster and had lower extinction rates than non monogamous populations. Another way that monogamy has the potential to cause increased speciation is because individuals are more selective with partners and competition, causing different nearby populations of the same species to stop interbreeding as much, leading to speciation down the road.

Another potential effect of polyandry in particular is increasing the quality of offspring and reducing the probability of reproductive failure. There are many possible reasons for this, one of the possibilities being that there is greater genetic variation in families because most offspring in a family will have either a different mother or father. This reduces the potential harm done by inbreeding, as siblings will be less closely related and more genetically diverse. Additionally, because of the increased genetic diversity among generations, the levels of reproductive fitness are also more variable, and so it is easier to select for positive traits more quickly, as the difference in fitness between members of the same generation would be greater. When many males are actively mating, polyandry can decrease the risk of extinction as well, as it can increase the effective population size. Increased effective population sizes are more stable and less prone to accumulating deleterious mutations due to genetic drift.

In microorganisms

Bacteria

Mating in bacteria involves transfer of DNA from one cell to another and incorporation of the transferred DNA into the recipient bacteria's genome by homologous recombination. Transfer of DNA between bacterial cells can occur in three main ways. First, a bacterium can take up exogenous DNA released into the intervening medium from another bacterium by a process called transformation. DNA can also be transferred from one bacterium to another by the process of transduction, which is mediated by an infecting virus (bacteriophage). The third method of DNA transfer is conjugation, in which a plasmid mediates transfer through direct cell contact between cells.

Transformation, unlike transduction or conjugation, depends on numerous bacterial gene products that specifically interact to perform this complex process, and thus transformation is clearly a bacterial adaptation for DNA transfer. In order for a bacterium to bind, take up and recombine donor DNA into its own chromosome, it must first enter a special physiological state termed natural competence. In Bacillus subtilis about 40 genes are required for the development of competence and DNA uptake. The length of DNA transferred during B. subtilis transformation can be as much as a third and up to the whole chromosome. Transformation appears to be common among bacterial species, and at least 60 species are known to have the natural ability to become competent for transformation. The development of competence in nature is usually associated with stressful environmental conditions, and seems to be an adaptation for facilitating repair of DNA damage in recipient cells.

Archaea

In several species of archaea, mating is mediated by formation of cellular aggregates. Halobacterium volcanii, an extreme halophilic archaeon, forms cytoplasmic bridges between cells that appear to be used for transfer of DNA from one cell to another in either direction.

When the hyperthermophilic archaea Sulfolobus solfataricus and Sulfolobus acidocaldarius are exposed to the DNA damaging agents UV irradiation, bleomycin or mitomycin C, species-specific cellular aggregation is induced. Aggregation in S. solfataricus could not be induced by other physical stressors, such as pH or temperature shift, suggesting that aggregation is induced specifically by DNA damage. Ajon et al. showed that UV-induced cellular aggregation mediates chromosomal marker exchange with high frequency in S. acidocaldarius. Recombination rates exceeded those of uninduced cultures by up to three orders of magnitude. Frols et al. and Ajon et al. hypothesized that cellular aggregation enhances species-specific DNA transfer between Sulfolobus cells in order to provide increased repair of damaged DNA by means of homologous recombination. This response appears to be a primitive form of sexual interaction similar to the more well-studied bacterial transformation systems that are also associated with species specific DNA transfer between cells leading to homologous recombinational repair of DNA damage.

Protists

Protists are a large group of diverse eukaryotic microorganisms, mainly unicellular animals and plants, that do not form tissues. Eukaryotes emerged in evolution more than 1.5 billion years ago. The earliest eukaryotes were likely protists. Mating and sexual reproduction are widespread among extant eukaryotes. Based on a phylogenetic analysis, Dacks and Roger proposed that facultative sex was present in the common ancestor of all eukaryotes.

However, to many biologists it seemed unlikely until recently, that mating and sex could be a primordial and fundamental characteristic of eukaryotes. A principal reason for this view was that mating and sex appeared to be lacking in certain pathogenic protists whose ancestors branched off early from the eukaryotic family tree. However, several of these protists are now known to be capable of, or to recently have had, the capability for meiosis and hence mating. To cite one example, the common intestinal parasite Giardia intestinalis was once considered to be a descendant of a protist lineage that predated the emergence of meiosis and sex. However, G. intestinalis was recently found to have a core set of genes that function in meiosis and that are widely present among sexual eukaryotes. These results suggested that G. intestinalis is capable of meiosis and thus mating and sexual reproduction. Furthermore, direct evidence for meiotic recombination, indicative of mating and sexual reproduction, was also found in G. intestinalis. Other protists for which evidence of mating and sexual reproduction has recently been described are parasitic protozoa of the genus Leishmania, Trichomonas vaginalis, and acanthamoeba.

Protists generally reproduce asexually under favorable environmental conditions, but tend to reproduce sexually under stressful conditions, such as starvation or heat shock.

Viruses

Both animal viruses and bacterial viruses (bacteriophage) are able to undergo mating. When a cell is mixedly infected by two genetically marked viruses, recombinant virus progeny are often observed indicating that mating interaction had occurred at the DNA level. Another manifestation of mating between viral genomes is multiplicity reactivation (MR). MR is the process by which at least two virus genomes, each containing inactivating genome damage, interact with each other in an infected cell to form viable progeny viruses. The genes required for MR in bacteriophage T4 are largely the same as the genes required for allelic recombination. Examples of MR in animal viruses are described in the articles Herpes simplex virus, Influenza A virus, Adenoviridae, Simian virus 40, Vaccinia virus, and Reoviridae.

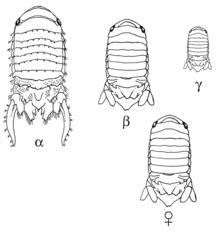

In arthropods

Fruit flies

Fruit flies like A. suspensa have demonstrated polygamy. The males often attract females through marking where they will perch and release air-borne pheromones from the tip of their abdomen to mark and defend individual leaves.