| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Codes_(United_States) |

The Black Codes, sometimes called the Black Laws, were laws which governed the conduct of African Americans (both free and freedmen). In 1832, James Kent wrote that "in most of the United States, there is a distinction in respect to political privileges, between free white persons and free colored persons of African blood; and in no part of the country do the latter, in point of fact, participate equally with the whites, in the exercise of civil and political rights." Although Black Codes existed before the Civil War and although many Northern states had them, the Southern U.S. states codified such laws in everyday practice. The best known of these laws were passed by Southern states in 1865 and 1866, after the Civil War, in order to restrict African Americans' freedom, and in order to compel them to work for either low or no wages.

Since the colonial period, colonies and states had passed laws that discriminated against free Blacks. In the South, these were generally included in "slave codes"; the goal was to suppress the influence of free blacks (particularly after slave rebellions) because of their potential influence on slaves. Restrictions included prohibiting them from voting (North Carolina had allowed this before 1831), bearing arms, gathering in groups for worship, and learning to read and write. The purpose of these laws was to preserve slavery in slave societies.

Before the war, Northern states that had prohibited slavery also enacted laws similar to the slave codes and the later Black Codes: Connecticut, Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, and New York enacted laws to discourage free blacks from residing in those states. They were denied equal political rights, including the right to vote, the right to attend public schools, and the right to equal treatment under the law. Some of the Northern states, those which had them, repealed such laws around the same time that the Civil War ended and slavery was abolished by constitutional amendment.

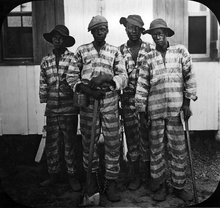

In the first two years after the Civil War, white legislatures passed Black Codes modeled after the earlier slave codes. (The name "Black Codes" was given by "negro leaders and the Republican organs", according to historian John S. Reynolds.) Black Codes were part of a larger pattern of Democrats trying to maintain political dominance and suppress the freedmen, newly emancipated African-Americans. They were particularly concerned with controlling movement and labor of freedmen, as slavery had been replaced by a free labor system. Although freedmen had been emancipated, their lives were greatly restricted by the Black Codes. The defining feature of the Black Codes was broad vagrancy law, which allowed local authorities to arrest freedpeople for minor infractions and commit them to involuntary labor. This period was the start of the convict lease system, also described as "slavery by another name" by Douglas Blackmon in his 2008 book of this title.

Background

Vagrancy laws date to the end of feudalism in Europe. Introduced by aristocratic and landowning classes, they had the dual purpose of restricting access of "undesirable" classes to public spaces and of ensuring a labor pool. Serfs were not emancipated from their land.

Before the Civil War

Southern states

"Black Codes" in the antebellum South strongly regulated the activities and behavior of blacks, especially free Blacks, who were not considered citizens. Chattel slaves basically lived under the complete control of their owners, so there was little need for extensive legislation. "All Southern states imposed at least minimal limits on slave punishment, for example, by making murder or life-threatening injury of slaves a crime, and a few states allowed slaves a limited right of self-defense." As slaves could not use the courts or sheriff, or give testimony against a white man, in practice these meant little.

North Carolina restricted slaves from leaving their plantation; if a male slave wished to court a female slave on another property, he needed a pass in order to pursue this relationship. Without one he risked severe punishment at the hands of the patrollers.

Free blacks presented a challenge to the boundaries of white-dominated society. In many Southern states, particularly after Nat Turner's insurrection of 1831, they were denied the rights of citizens to assemble in groups, bear arms, learn to read and write, exercise free speech, or testify against white people in Court. After 1810, states made manumissions of slaves more difficult to obtain, in some states requiring an act of the legislature for each case of manumission. This sharply reduced the incidence of planters freeing slaves.

All the slave states passed anti-miscegenation laws, banning the marriage of white and black people.

Between 1687 and 1865, Virginia enacted more than 130 slave statutes, among which were seven major slave codes, with some containing more than fifty provisions.

Slavery wus a bad thing en' freedom, of de kin' we got wid nothin' to live on wus bad. Two snakes full of pisen. One lying wid his head pintin' north, de other wid his head pintin' south. Dere names wus slavery an' freedom. De snake called slavery lay wid his head pinted south and de snake called freedom lay wid his head pinted north. Both bit de nigger, an' dey wus both bad.

—Patsy Mitchner, former slave in Raleigh, NC; interviewed in 1937 (at age 84) for the Slave Narrative Collection of the Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration.

Maryland passed vagrancy and apprentice laws, and required Blacks to obtain licenses from Whites before doing business. It prohibited immigration of free Blacks until 1865. Most of the Maryland Black Code was repealed in the Constitution of 1867. Black women were not allowed to testify against white men with whom they had children, giving them a status similar to wives.

Northern states

As the abolitionist movement gained force and the Underground Railroad helped fugitive slaves escape to the North, concern about Black people heightened among Northern white people. Territories and states near the slave states did not welcome freed Black people. But north of the Mason–Dixon line, anti-Black laws were generally less severe. Some public spaces were segregated, and Black people generally did not have the right to vote. In Oregon, Black people were forbidden to settle, marry, or sign contracts. In Ohio, Black people required a certificate they were free and a good behavior bond.

All the slave states passed anti-miscegenation laws, banning the marriage of white and Black people, as did several new free states of the former Northwest Territory, including Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan. Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois shared borders with the slave states across the Ohio and Mississippi rivers (Kentucky, Missouri, and Virginia respectively). The population of the southern parts of these states had generally migrated from the Upper South; their culture and values were more akin to those of the South across the river than those of the northern settlers, who had migrated from New England and New York. In some states these codes included vagrancy laws that targeted unemployed Black people, apprentice laws that made Black orphans and dependents available for hire to white people, and commercial laws that excluded Black people from certain trades and businesses and restricted their ownership of property.

The Indiana Legislature decreed in 1843 that only white students could attend the public schools. Article 13 of Indiana's 1851 Constitution banned Black people from settling in the state. Anyone who helped Black people settle in the state or employed Black settlers could be fined. Article 13 had the most popular vote among Hoosiers compared to all other articles voted upon. The Supreme Court declared Article 13 invalid in 1866.

The 1848 Constitution of Illinois contributed to the state legislature passing one of the harshest Black Code systems in the nation until the Civil War. The Illinois Black Code of 1853 prohibited any Black persons from outside of the state from staying in the state for more than ten days, subjecting Black people who violated that rule to arrest, detention, a $50 fine, or deportation. However, while slavery was illegal in Illinois, landowners in the southern parts of the state would legally bring in slaves from adjacent Kentucky, and force them to do agricultural work for no wages. They had to be removed from the state for one day each year, thus preventing them from being citizens of Illinois and receiving the protection of its laws. A campaign to repeal these laws was led by John Jones, Chicago's most prominent black citizen. In December 1850, Jones circulated a petition—signed by black residents of the state—for Illinois legislators to repeal the Black Laws. In 1864, the Chicago Tribune published Jones’ pamphlet, “The Black Laws of Illinois and a Few Reasons Why They Should Be Repealed.” It was not until 1865 that Illinois repealed the state’s provision of its Black Laws.

In some states, Black Code legislation used text directly from the slave codes, simply substituting Negro or other words in place of slave.

Under Union occupation

The Union Army relied on the labor of newly freed people, and did not always treat them fairly. Thomas W. Knox wrote: "The difference between working for nothing as a slave, and working for the same wages under the Yankees, was not always perceptible." At the same time, military officials resisted local attempts to apply pre-war laws to the freed people. After the Emancipation Proclamation, the Army conscripted Black "vagrants" and sometimes others.

The Union Army applied the northern wage system of free labor to freedmen after the Emancipation Proclamation; they effectively upgraded free Blacks from "contraband" status. General Nathaniel P. Banks in Louisiana initiated a system of wage labor in February 1863 in Louisiana; General Lorenzo Thomas implemented a similar system in Mississippi. The Banks-Thomas system offered Blacks $10 a month, with the Army's commitment to provide rations, clothing, and medicine. The worker would have to agree to an unbreakable one-year contract. In 1864, Thomas expanded the system to Tennessee, and allowed white landowners near the Nashville contraband camp to rent the labor of refugees.

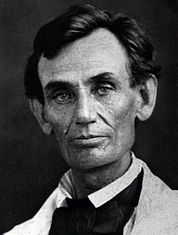

Against opposition from elements of the Republican Party, Abraham Lincoln accepted this system as a step on the path to gradual emancipation. Abolitionists continued to criticize the labor system. Wendell Phillips said that Lincoln's proclamation had "free[d] the slave, but ignore[d] the Negro", calling the Banks-Thomas year-long contracts tantamount to serfdom. The Worcester Spy described the government's answer to slavery as "something worse than failure."

Post-Civil War years

As the war ended, the U.S. Army implemented Black Codes to regulate the behavior of black people in general society. Although the Freedmen's Bureau had a mandate to protect blacks from a hostile Southern environment, it also sought to keep blacks in their place as laborers in order to allow production on the plantations to resume so that the South could revive its economy. The Freedmen's Bureau cooperated with Southern authorities in rounding up black "vagrants" and placing them in contract work. In some places, it supported owners to maintain control of young slaves as apprentices.

New restrictions were placed on intermarriage, concubinage, and miscegenation with Black people in Arizona in 1864, California in 1880, Colorado in 1864, Florida, Indiana in 1905, Kentucky in 1866, Montana in 1909, Nebraska in 1865, Nevada in 1912, North Dakota in 1943, Ohio 1877, Oregon in 1867, Rhode Island in 1872, South Dakota in 1913, Tennessee in 1870, Texas in 1858, Utah in 1888, Virginia, Washington in 1866 but promptly repealed it in 1867, West Virginia in 1863 but overturned by Loving v Virginia in 1967, and Wyoming in 1908. In all, twenty-one states put in place Jim Crow laws against miscegenation. Free whites could no longer marry a slave and thereby emancipate her and her children, and no freedman could receive a donation or inheritance from a white person.

Soon after the end of slavery, white planters encountered a labor shortage and sought a way to manage it. Although blacks did not all abruptly stop working, they did try to work less. In particular, many sought to reduce their Saturday work hours, and women wanted to spend more time on child care. In the view of one contemporary economist, freed people exhibited this "noncapitalist behavior" because the condition of being owned had "shielded the slaves from the market economy" and they were therefore unable to perform "careful calculation of economic opportunities".

An alternative explanation treats the labor slowdown as a form of gaining leverage through collective action. Another possibility is that freed blacks assigned value to leisure and family time in excess of the monetary value of additional paid labor. Indeed, freedpeople certainly did not want to work the long hours that had been forced upon them for their whole lives. Whatever its causes, the sudden reduction of available labor posed a challenge to the Southern economy, which had relied upon intense physical labor to profitably harvest cash crops, particularly King Cotton.

Southern Whites also perceived Black vagrancy as a sudden and dangerous social problem.

Preexisting White American belief of Black inferiority informed post-war attitudes and White racial dominance continued to be culturally embedded; Whites believed both that Black people were destined for servitude and that they would not work unless physically compelled. The enslaved strove to create a semi-autonomous social world, removed from the plantation and the gaze of the slave owner. The racial divisions that slavery had created immediately became more obvious. Blacks also bore the brunt of Southern anger over defeat in the War.

Legislation on the status of freedpeople was often mandated by constitutional conventions held in 1865. Mississippi, South Carolina, and Georgia all included language in their new state constitutions which instructed the legislature to "guard them and the State against any evils that may arise from their sudden emancipation". The Florida convention of October 1865 included a vagrancy ordinance that was in effect until process Black Codes could be passed through the regular legislative process.

Black Codes restricted black people's right to own property, conduct business, buy and lease land, and move freely through public spaces. A central element of the Black Codes were vagrancy laws. States criminalized men who were out of work, or who were not working at a job whites recognized. Failure to pay a certain tax, or to comply with other laws, could also be construed as vagrancy.

Nine Southern states updated their vagrancy laws in 1865–1866. Of these, eight allowed convict leasing (a system in which state prison hired out convicts for labor) and five allowed prisoner labor for public works projects. This created a system that established incentives to arrest black men, as convicts were supplied to local governments and planters as free workers. The planters or other supervisors were responsible for their board and food, and black convicts were kept in miserable conditions. As Douglas Blackmon wrote, it was "slavery by another name". Because of their reliance on convict leasing, Southern states did not build any prisons until the late 19th century.

Another important part of the Codes were the annual labor contracts, which Black people had to keep and present to authorities to avoid vagrancy charges.

Strict punishments against theft also served to ensnare many people in the legal system. Previously, Blacks had been part of the domestic economy on a plantation, and were more or less able to use supplies that were available. After emancipation, the same act performed by someone working the same land might be labeled as theft, leading to arrest and involuntary labor.

Some states explicitly curtailed Black people's right to bear arms, justifying these laws with claims of imminent insurrection. In Mississippi and Alabama, these laws were enforced through the creation of special militias.

Historian Samuel McCall, who published a biography of abolitionist Thaddeus Stevens, commented in 1899 that the Black Codes had "established a condition but little better than that of slavery, and in one important respect far worse": by severing the property relationship, they had diminished the incentive for property owners to ensure the relative health and survival of their workers.

Regarding the question of whether Southern legislatures deliberately tried to maintain white supremacy, Beverly Forehand writes: "This decision was not a conscious one on the part of white legislators. It was simply an accepted conclusion."

During Reconstruction, state legislatures passed some laws that established some positive rights for freedmen. States legalized Black marriages and in some cases increased the rights of freedmen to own property and conduct commerce.

Reconstruction and Jim Crow

|

The Black Codes outraged public opinion in the North because it seemed the South was creating a form of quasi-slavery to negate the results of the war. When the Radical 39th Congress re-convened in December 1865, it was generally furious about the developments that had transpired during Johnson's Presidential Reconstruction. The Black Codes, along with the appointment of prominent Confederates to Congress, signified that the South had been emboldened by Johnson and intended to maintain its old political order. Railing against the Black Codes as returns to slavery in violation of the Thirteenth Amendment, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, the Fourteenth Amendment, and the Second Freedmen's Bureau Bill.

The Memphis Riots in May 1866 and the New Orleans Riot in July brought additional attention and urgency to the racial tension state-sanctioned racism permeating the South.

After winning large majorities in the 1866 elections, the Republican Congress passed the Reconstruction Acts placing the South under military rule. This arrangement lasted until the military withdrawal arranged by the Compromise of 1877. In some historical periodizations, 1877 marks the beginning of the Jim Crow era.

The 1865–1866 Black Codes were an overt manifestation of the system of white supremacy that continued to dominate the American South. Historians have described this system as the emergent result of a wide variety of laws and practices, conducted on all levels of jurisdiction. Because legal enforcement depended on so many different local codes, which underwent less scrutiny than statewide legislation, historians still lack a complete understanding of their full scope. It is clear, however, that even under military rule, local jurisdictions were able to continue a racist pattern of law enforcement, as long as it took place under a legal regime that was superficially race-neutral.

In 1893–1909 every Southern state except Tennessee passed new vagrancy laws. These laws were more severe than those passed in 1865, and used vague terms that granted wide powers to police officers enforcing the law. An example were the so-called "Pig Laws", with harsh penalties for crimes such as stealing a farm animal. Pig Laws were solely applied to African Americans related to agricultural crimes. In wartime, Blacks might be disproportionately subjected to "work or fight" laws, which increased vagrancy penalties for those not in the military. The Supreme Court upheld racially discriminatory state laws and invalidated federal efforts to counteract them; in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) it upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation and introduced the "separate but equal" doctrine.

A general system of legitimized anti-Black violence, as exemplified by the Ku Klux Klan, played a major part in enforcing the practical law of white supremacy. The constant threat of violence against Black people (and White people who sympathized with them) maintained a system of extralegal terror. Although this system is now well known for prohibiting Black suffrage after the Fifteenth Amendment, it also served to enforce coercive labor relations. Fear of random violence provided new support for a paternalistic relationship between plantation owners and their Black workers.

Mississippi

Mississippi was the first state to pass Black Codes. Its laws served as a model for those passed by other states, beginning with South Carolina, Alabama, and Louisiana in 1865, and continuing with Florida, Virginia, Georgia, North Carolina, Texas, Tennessee, and Arkansas at the beginning of 1866. Intense Northern reaction against the Mississippi and South Carolina laws led some of the states that subsequently passed laws to excise overt racial discrimination; but, their laws on vagrancy, apprenticeship, and other topics were crafted to effect a similarly racist regime. Even states that carefully eliminated most of the overt discrimination in their Black Codes retained laws authorizing harsher sentences for Black people.

Mississippi was the first state to legislate a new Black Code after the war, beginning with "An Act to confer Civil Rights on Freedmen". This law allowed Blacks to rent land only within cities—effectively preventing them from earning money through independent farming. It required Blacks to present, each January, written proof of employment. The law defined violation of this requirement as vagrancy, punishable by arrest—for which the arresting officer would be paid $5, to be taken from the arrestee's wages. Provisions akin to fugitive slave laws mandated the return of runaway workers, who would lose their wages for the year. An amended version of the vagrancy law included punishments for sympathetic whites:

That all freedmen, free negroes and mulattoes in this State, over the age of eighteen years, found on the second Monday in January, 1866, or thereafter, without lawful employment or business, or found unlawfully assembling themselves together, either in the day or night time, and all white persons so assembling themselves with freedmen, free negroes or mulattoes, or usually associating with freedmen, free negroes or mulattoes, on terms of equality, or living in adultery or fornication with a freed woman, free negro or mulatto, shall be deemed vagrants, and on conviction thereof shall be fined in a sum not exceeding, in the case of a freedman, free negro, or mulatto, fifty dollars, and a white man two hundred dollars, and imprisoned, at the discretion of the court, the free negro not exceeding ten days, and the white man not exceeding six months.

Whites could avoid the code's penalty by swearing a pauper's oath. In the case of blacks, however: "the duty of the sheriff of the proper county to hire out said freedman, free negro or mulatto, to any person who will, for the shortest period of service, pay said fine or forfeiture and all costs." The laws also levied a special tax on blacks (between ages 18 and 60); those who did not pay could be arrested for vagrancy.

Another law allowed the state to take custody of children whose parents could or would not support them; these children would then be "apprenticed" to their former owners. Masters could discipline these apprentices with corporal punishment. They could re-capture apprentices who escaped and threaten them with prison if they resisted.

Other laws prevented blacks from buying liquor and carrying weapons; punishment often involved "hiring out" the culprit's labor for no pay.

Mississippi rejected the Thirteenth Amendment on December 5, 1865.

General Oliver O. Howard, national head of the Freedmen's Bureau, declared in November 1865 that most of the Mississippi Black Code was invalid.

South Carolina

The next state to pass Black Codes was South Carolina, which had on November 13 ratified the Thirteenth Amendment—with a qualification that Congress did not have the authority to regulate the legal status of freedmen. Newly elected governor James Lawrence Orr said that blacks must be "restrained from theft, idleness, vagrancy and crime, and taught the absolute necessity of strictly complying with their contracts for labor".

South Carolina's new law on "Domestic Relations of Persons of Color" established wide-ranging rules on vagrancy resembling Mississippi's. Conviction for vagrancy allowed the state to "hire out" blacks for no pay. The law also called for a special tax on blacks (all males and unmarried females), with non-paying blacks again guilty of vagrancy. The law enabled forcible apprenticeship of children of impoverished parents, or of parents who did not convey "habits of industry and honesty". The law did not include the same punishments for Whites in dealing with fugitives.

The South Carolina law created separate courts for Black people, and authorized capital punishment for crimes including theft of cotton. It created a system of licensing and written authorizations that made it difficult for Blacks to engage in normal commerce.

The South Carolina Code clearly borrowed terms and concepts from the old slave codes, re-instituting a rating system of "full" or "fractional" farmhands and often referring to bosses as "masters".

Responses

A "Colored People's Convention" assembled at Zion Church in Charleston, South Carolina, to condemn the Codes. In a memorial (petition) to Congress, the Convention expressed gratitude for emancipation and establishment of the Freedmen's Bureau, but requested (in addition to suffrage) "that the strong arm of law and order be placed alike over the entire people of this State; that life and property be secured, and the laborer as free to sell his labor as the merchant his goods."

Some people, meanwhile, thought the new laws did not go far enough. One planter suggested that the new laws would require paramilitary enforcement: "As for making the negroes work under the present state of affairs it seems to me a waste of time and energy ... We must have mounted Infantry that the freedmen know distinctly that they succeed the Yankees to enforce whatever regulations we can make." Edmund Rhett (son of Robert Rhett) wrote that although South Carolina might be unable to undo abolition,

it should to the utmost extent practicable be limited, controlled, and surrounded with such safe guards, as will make the change as slight as possible both to the white man and to the negro, the planter and the workman, the capitalist and the laborer.

General Daniel Sickles, head of the Freedmen's Bureau in South Carolina, followed Howard's lead and declared the laws invalid in December 1865.

Further legislation

Even as the legislators passed these laws, they despaired of the forthcoming response from Washington. James Hemphill said: "It will be hard to persuade the freedom shriekers that the American citizens of African descent are obtaining their rights." Orr moved to block further laws containing explicit racial discrimination. In 1866, the South Carolina code came under increasing scrutiny in the Northern press and was compared unfavorably to freedmen's laws passed in neighboring Georgia, North Carolina, and Virginia.

In a special session held in September 1866, the legislature passed some new laws in concession to the rights of free Blacks. Shortly after, it rejected the Fourteenth Amendment.

Louisiana

The Louisiana legislature, seeking to ensure that freedmen were "available to the agricultural interests of the state", passed similar yearly contract laws and expanded its vagrancy laws. Its vagrancy laws did not specify Black culprits, though they did provide a "good behavior" loophole subject to plausibly racist interpretation. Louisiana passed harsher fugitive worker laws and required blacks to present dismissal paperwork to new employers.

State legislation was amplified by local authorities, who ran less risk of backlash from the federal government. Opelousas, Louisiana, passed a notorious code which required freedpeople to have written authorization to enter the town. The code prevented freedpeople from living in the town or walking at night except under supervision of a White resident.

Thomas W. Conway, the Freedmen's Bureau commissioner for Louisiana, testified in 1866:

Some of the leading officers of the state down there—men who do much to form and control the opinions of the masses—instead of doing as they promised, and quietly submitting to the authority of the government, engaged in issuing slave codes and in promulgating them to their subordinates, ordering them to carry them into execution, and this to the knowledge of state officials of a higher character, the governor and others. ... These codes were simply the old black code of the state, with the word 'slave' expunged, and 'Negro' substituted. The most odious features of slavery were preserved in them.

Conway describes surveying the Louisiana jails and finding large numbers of Black men who had been secretly incarcerated. These included members of the Seventy-Fourth Colored Infantry who had been arrested the day after they were discharged.

The state passed a harsher version of its code in 1866, criminalizing "impudence", "swearing", and other signs of "disobedience" as determined by whites.

Florida

Of the Black Codes passed in 1866 (after the Northern reaction had become apparent), only Florida's rivaled those of Mississippi and South Carolina in severity. Florida's slaveowners seemed to hold out hope that the institution of slavery would simply be restored. Advised by the Florida governor and attorney general as well as by the Freedmen's Bureau that it could not constitutionally revoke Black people's right to bear arms, the Florida legislature refused to repeal this part of the codes.

The Florida vagrancy law allowed for punishments of up to one year of labor. Children whose parents were convicted of vagrancy could be hired out as apprentices.

These laws applied to any "person of color", which was defined as someone with at least one Negro great-grandparent, or one-eighth black ancestry. White women could not live with men of color. Colored workers could be punished for disrespecting White employers. The explicit racism in the law was supplemented by racist enforcement discretion (and other inequalities) in the practice of law enforcement and legal systems.

Maryland

In Maryland, a fierce battle began immediately after emancipation (by the Maryland Constitution of 1864) over requiring apprenticeship of young black people. By 1860, 45.6% of the black population in the state was already free. Former slave owners rushed to place the children of freedpeople in multi-year apprenticeships; the Freedmen's Bureau and some others tried to stop them. The legislature stripped Baltimore Judge Hugh Lennox Bond of his position because he cooperated with the Bureau in this matter. Salmon Chase, as Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, eventually overruled the Maryland apprentice laws on the grounds of their violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

North Carolina

North Carolina's Black Code specified racial differences in punishment, establishing harsher sentences for Black people convicted of rape.

Texas

The Texas Constitutional Convention met in February 1866, declined to ratify the (already effective) Thirteenth Amendment, provided that Blacks would be "protected in their rights of person and property by appropriate legislation" and guaranteed some degree of rights to testify in court. Texas modeled its laws on South Carolina's.

The legislature defined "Negroes" as people with at least one African great-grandparent. "Negroes" could choose their employer, before a deadline. After they had made a contract, they were bound to it. If they quit "without cause of permission" they would lose all of their wages. Workers could be fined $1 for acts of disobedience or negligence, and 25 cents per hour for missed work. The legislature also created a system of apprenticeship (with corporal punishment) and vagrancy laws. Convict labor could be hired out or used in public works.

"Negroes" were not allowed to vote, hold office, sit on juries, serve in local militia, carry guns on plantations, homestead, or attend public schools. Interracial marriage was banned. Rape sentencing laws stipulated either capital punishment, or life in prison, or a minimum sentence of five years. Even to commentators who favored the codes, this "wide latitude in punishment" seemed to imply a clear "anti-Negro bias".

Tennessee

Tennessee had been occupied by the Union for a long period during the war. As military governor of Tennessee, Andrew Johnson declared a suspension of the slave code in September 1864. However, these laws were still enforced in lower courts. In 1865, Tennessee freedpeople had no legal status whatsoever, and local jurisdictions often filled the void with extremely harsh Black Codes. During that year, Blacks went from one-fiftieth to one-third of the State's prison population.

Tennessee had a particularly urgent desire to re-enter the Union's good graces and end the occupation. When the Tennessee Legislature began to debate a Black Code, it received such negative attention in the Northern press that no comprehensive Code was ever established. Instead, the State legalized Black suffrage and passed a civil rights law guaranteeing Blacks equal rights in commerce and access to the Courts.

However, Tennessee society, including its judicial system, retained the same racist attitudes as did other states. Although its legal code did not discriminate against Blacks so explicitly, its law enforcement and criminal justice systems relied more heavily on racist enforcement discretion to create a de facto Black Code. The state already had vagrancy and apprenticeship laws which could easily be enforced in the same way as Black Codes in other states. Vagrancy laws came into much more frequent use after the war. And just as in Mississippi, Black children were often bound in apprenticeship to their former owners.

The legislature passed two laws on May 17, 1865; one to "Punish all Armed Prowlers, Guerilla, Brigands, and Highway Robbers"; the other to authorize capital punishment for thefts, burglary, and arson. These laws were targeted at Blacks and enforced disproportionately against Blacks, but did not discuss race explicitly.

Tennessee law permitted Blacks to testify against Whites in 1865, but this change did not immediately take practical effect in the lower courts. Blacks could not sit on juries. Still on the books were laws specifying capital punishment for a Black man who raped a White woman.

Tennessee enacted new vagrancy and enticement laws in 1875.

Kentucky

Kentucky had established a system of leasing prison labor in 1825. This system drew a steady supply of laborers from the decisions of "negro courts", informal tribunals which included slaveowners. Free Blacks were frequently arrested and forced into labor.

Kentucky did not secede from the Union and therefore gained wide leeway from the federal government during Reconstruction. With Delaware, Kentucky did not ratify the Thirteenth Amendment and maintained legal slavery until it was nationally prohibited when the Amendment went into effect in December 1865. After the Thirteenth Amendment took effect, the state was obligated to rewrite its laws.

The result was a set of Black Codes passed in early 1866. These granted a set of rights: to own property, make contracts, and some other innovations. They also included new vagrancy and apprentice laws, which did not mention Blacks explicitly but were clearly directed toward them. The vagrancy law covered loitering, "rambling without a job" and "keeping a disorderly house". City jails filled up; wages dropped below pre-war rates.

The Freedmen's Bureau in Kentucky was especially weak and could not mount a significant response. The Bureau attempted to cancel a racially discriminatory apprenticeship law (which stipulated that only White children learn to read) but found itself thwarted by local authorities.

Some legislation also created informal, de facto discrimination against Blacks. A new law against hunting on Sundays, for example, prevented Black workers from hunting on their only day off.

Kentucky law prevented Blacks from testifying against Whites, a restriction which the federal government sought to remedy by providing access to federal courts through the Civil Rights Act of 1866. Kentucky challenged the constitutionality of these courts and prevailed in Blyew v. United States (1872). All contracts required the presence of a White witness. Passage of the Fourteenth Amendment did not have a great effect on Kentucky's Black Codes.

Legacy and interventions

This regime of white-dominated labor was not identified by the North as involuntary servitude until after 1900. In 1907, Attorney General Charles Joseph Bonaparte issued a report, Peonage Matters, which found that, beyond debt peonage, there was a widespread system of laws "considered to have been passed to force negro laborers to work".

After creating the Civil Rights Section in 1939, the Federal Department of Justice launched a wave of successful Thirteenth Amendment prosecutions against involuntary servitude in the South.

Many of the Southern vagrancy laws remained in force until the Supreme Court's Papachristou v. Jacksonville decision in 1972. Although the laws were defended as preventing crime, the Court held that Jacksonville's vagrancy law "furnishes a convenient tool for 'harsh and discriminatory enforcement by local prosecuting officials, against particular groups deemed to merit their displeasure.'"

Even after Papachristou, police activity in many parts of the United States discriminates against racial minority groups. Gary Stewart has identified contemporary gang injunctions—which target young Black or Latino men who gather in public—as a conspicuous legacy of Southern Black Codes. Stewart argues that these laws maintain a system of white supremacy and reflect a system of racist prejudice, even though racism is rarely acknowledged explicitly in their creation and enforcement. Contemporary Black commentators have argued that the current disproportionate incarceration of African Americans, with a concomitant rise in prison labor, is comparable (perhaps unfavorably) with the historical Black Codes.

Comparative history

The desire to recuperate the labor of officially emancipated people is common among societies (most notably in Latin America) that were built on slave labor. Vagrancy laws and peonage systems are widespread features of post-slavery societies. One theory suggests that particularly restrictive laws emerge in larger countries (compare Jamaica with the United States) where the ruling group does not occupy land at a high enough density to prevent the freed people from gaining their own. It seems that the United States was uniquely successful in maintaining involuntary servitude after legal emancipation.

Historians have also compared the end of the slavery in the United States to the formal decolonization of Asian and African nations. Like emancipation, decolonization was a landmark political change—but its significance, according to some historians, was tempered by the continuity of economic exploitation. The end of legal slavery in the United States did not seem to have major effects on the global economy or international relations. Given the pattern of economic continuity, writes economist Pieter Emmer, "the words emancipation and abolition must be regarded with the utmost suspicion."