Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, owned more than 600 slaves during his adult life. Jefferson freed two slaves while he lived, and five others were freed after his death, including two of his children from his relationship with his slave (and sister-in-law) Sally Hemings. His other two children with Hemings were allowed to escape without pursuit. After his death, the rest of the slaves were sold to pay off his estate's debts.

Privately, one of Jefferson's reasons for not freeing more slaves was his considerable debt, while his more public justification, expressed in his book Notes on the State of Virginia, was his fear that freeing enslaved people into American society would cause civil unrest between white people and former slaves.

Jefferson consistently spoke out against the international slave trade and outlawed it while he was president. He advocated for a gradual emancipation of all slaves within the United States and the colonization of Africa by freed African Americans. However, he opposed some other measures to restrict slavery within the U.S., and also criticized voluntary manumission.

Early years (1743–1774)

Thomas Jefferson was born into the planter class of a "slave society", as defined by the historian Ira Berlin, in which slavery was the main means of labor production. He was the son of Peter Jefferson, a prominent slaveholder and land speculator in Virginia, and Jane Randolph, granddaughter of English and Scots gentry. In 1757, when Jefferson was 14, his father died, and so he inherited 5,000 acres (20 km2) of land, 52 slaves, livestock, his father's notable library, and a gristmill. This property was initially under control of his guardian, John Harvie Sr. He assumed full control over these properties at age 21. In 1768, Thomas Jefferson began construction of a neoclassical mansion known as Monticello, which overlooked the hamlet of his former home in Shadwell. As an attorney, Jefferson represented people of color as well as whites. In 1770, he defended a young mixed-race male slave in a freedom suit, on the grounds that his mother was white and freeborn. By the colony's law of partus sequitur ventrem, that the child took the status of the mother, the man should never have been enslaved. He lost the suit. In 1772, Jefferson represented George Manly, the son of a free woman of color, who sued for freedom after having been held as an indentured servant three years past the expiration of his term. (The Virginia colony at the time bound illegitimate mixed-race children of free women as indentured servants: until age 31 for males, with a shorter term for females.) Once freed, Manly worked for Jefferson at Monticello for wages.

In 1773, the year after Jefferson married the young widow Martha Wayles Skelton, her father died. She and Jefferson inherited his estate, including 11,000 acres, 135 slaves, and £4,000 of debt. With this inheritance, Jefferson became deeply involved with interracial families and financial burden. As a widower, his father-in-law John Wayles had taken his mixed-race slave Betty Hemings as a concubine and had six children with her during his last 12 years.

These additional forced laborers made Jefferson the second-largest slaveholder in Albemarle County. In addition, he held nearly 16,000 acres of land in Virginia. He sold some people to pay off the debt of Wayles' estate. From this time on, Jefferson owned and supervised his large chattel estate, primarily at Monticello, although he also developed other plantations in the colony. Slavery supported the life of the planter class in Virginia.

In collaboration with Monticello, now the major public history site on Jefferson, the Smithsonian opened on the National Mall an exhibit, Slavery at Jefferson's Monticello: The Paradox of Liberty, (January – October 2012) at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. It covered Jefferson as a slaveholder and the roughly 600 enslaved people who lived at Monticello over the decades, with a focus on six enslaved families and their descendants. It was the first national exhibit on the Mall to address these issues. In February 2012, Monticello opened a related new outdoor exhibition, Landscape of Slavery: Mulberry Row at Monticello, which "brings to life the stories of the scores of people—enslaved and free—who lived and worked on Jefferson's 5,000 acre plantation."

Shortly after ending his law practice in 1774, Jefferson wrote A Summary View of the Rights of British America, which was submitted to the First Continental Congress. In it, he argued Americans were entitled to all the rights of British citizens, and denounced King George for wrongfully usurping local authority in the colonies. In regard to slavery, Jefferson wrote "The abolition of domestic slavery is the great object of desire in those colonies, where it was unhappily introduced in their infant state. But previous to the enfranchisement of the slaves we have, it is necessary to exclude all further importations from Africa; yet our repeated attempts to effect this by prohibitions, and by imposing duties which might amount to a prohibition, have been hitherto defeated by his majesty's negative: Thus preferring the immediate advantages of a few African corsairs to the lasting interests of the American states, and to the rights of human nature, deeply wounded by this infamous practice."

Revolutionary period (1775–1783)

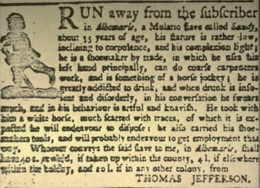

In 1775, Thomas Jefferson joined the Continental Congress as a delegate from Virginia when he and others in Virginia began to rebel against the Royal Governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore. Trying to reassert British authority over the area, Dunmore issued a Proclamation in November 1775 that offered freedom to slaves who abandoned their Patriot masters and joined the British. Dunmore's action led to a mass exodus of tens of thousands of forced laborers from plantations across the South during the war years; some of the people Jefferson held as slaves also took off as runaways.

The colonists opposed Dunmore's action as an attempt to incite a massive slave rebellion. In 1776, when Jefferson co-authored the Declaration of Independence, he referred to the Lord Governor when he wrote, "He has excited domestic insurrections among us," though the institution of slavery itself was never mentioned by name at any point in the document. In the original draft of the Declaration, Jefferson inserted a clause condemning King George III for forcing the slave trade onto the American colonies and inciting enslaved African Americans to "rise in arms" against their masters:

He has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. This piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers, is the warfare of the Christian King of Great Britain. Determined to keep open a market where Men should be bought & sold, he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or restrain this execrable commerce. And that this assemblage of horrors might want no fact of distinguished die, he is now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase that liberty of which he has deprived them, by murdering the people on whom he has obtruded them: thus paying off former crimes committed against the Liberties of one people, with crimes which he urges them to commit against the lives of another.

— BlackPast, The Declaration of Independence and the Debate Over Slavery

The Continental Congress, however, due to Southern opposition, forced Jefferson to delete the clause in the final draft of the Declaration. Jefferson did manage to make a general criticism against slavery by maintaining "all men are created equal." Jefferson did not directly condemn domestic slavery as such in the Declaration, as Jefferson himself was a slaveowner. According to Finkelman, "The colonists, for the most part, had been willing and eager purchasers of slaves." Researcher William D. Richardson proposed that Thomas Jefferson's use of "MEN" in capital letters would be a repudiation of those who may believe that the Declaration was not including slaves with the word "Mankind".

That same year, Jefferson submitted a draft for the new Virginia Constitution containing the phrase "No person hereafter coming into this country shall be held within the same in slavery under any pretext whatever." His proposal was not adopted.

In 1778 with Jefferson's leadership and probably authorship, the Virginia General Assembly banned importing people to be used as slaves into Virginia. It was one of the first jurisdictions in the world to ban the international slave trade, and all other states except South Carolina eventually followed prior to the Congress banning the trade in 1807.

As governor of Virginia for two years during the Revolution, Jefferson signed a bill to promote military enlistment by giving white men land, "a healthy sound Negro ... or £60 in gold or silver." As was customary, he brought some of the household workers he held in slavery, including Mary Hemings, to serve in the governor's mansion in Richmond. Facing a British invasion in January 1781, Jefferson and the Assembly members fled the capital and moved the government to Charlottesville, leaving the workers enslaved by Jefferson behind. Hemings and other enslaved people were taken by the British as prisoners of war; they were later released in exchange for captured British soldiers. In 2009, the Daughters of the Revolution (DAR) honored Mary Hemings as a Patriot, making her female descendants eligible for membership in the heritage society.

In June 1781, the British arrived at Monticello. Jefferson had escaped before their arrival and gone with his family to his plantation of Poplar Forest to the southwest in Bedford County; most of those he held as slaves stayed at Monticello to help protect his valuables. The British did not loot or take prisoners there. By contrast, Lord Cornwallis and his troops occupied and looted another planation owned by Jefferson, Elkhill in Goochland County, Virginia, northwest of Richmond. Of the 30 enslaved people they took as prisoners, Jefferson later claimed that at least 27 had died of disease in their camp.

While claiming since the 1770s to support gradual emancipation, as a member of the Virginia General Assembly Jefferson declined to support a law to ask that, saying the people were not ready. After the United States gained independence, in 1782 the Virginia General Assembly repealed the slave law of 1723 and made it easier for slaveholders to manumit slaves. Unlike some of his planter contemporaries, such as Robert Carter III, who freed nearly 500 people held slaves in his lifetime, or George Washington, who freed all the enslaved people he legally owned, in his will of 1799, Jefferson formally freed only two people during his life, in 1793 and 1794. Virginia did not require freed people to leave the state until 1806. From 1782 to 1810, as numerous slaveholders freed enslaved people, the proportion of free blacks in Virginia increased dramatically from less than 1% to 7.2% of blacks.

Following the Revolution (1784–1800)

Some historians have claimed that, as a Representative to the Continental Congress, Thomas Jefferson wrote an amendment or bill that would abolish slavery. But according to Finkelman, "he never did propose this plan" and "Jefferson refused to propose either a gradual emancipation scheme or a bill to allow individual masters to free their slaves." He refused to add gradual emancipation as an amendment when others asked him to; he said, "better that this should be kept back." In 1785, Jefferson wrote to one of his colleagues that black people were mentally inferior to white people, claiming the entire race was incapable of producing a single poet.

On March 1, 1784, in defiance of southern slave society, Jefferson submitted to the Continental Congress the Report of a Plan of Government for the Western Territory. "The provision would have prohibited slavery in *all* new states carved out of the western territories ceded to the national government established under the Articles of Confederation." Slavery would have been prohibited extensively in both the North and South territories, including what would become Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee. His Ordinance of 1784 would have prohibited slavery completely by 1800 in all territories, but was rejected by the Congress by one vote due to an absent representative from New Jersey. On April 23, Congress accepted Jefferson's 1784 Ordinance, but removed the clause prohibiting slavery in all the territories. Jefferson said that southern representatives defeated his original proposal. Jefferson was only able to obtain one southern delegate to vote for the prohibition of slavery in all territories. The Library of Congress notes, "The Ordinance of 1784 marks the high point of Jefferson's opposition to slavery, which is more muted thereafter." In 1786, Jefferson bitterly remarked "The voice of a single individual of the state which was divided, or of one of those which were of the negative, would have prevented this abominable crime from spreading itself over the new country. Thus we see the fate of millions unborn hanging on the tongue of one man, & heaven was silent in that awful moment!" Jefferson's Ordinance of 1784 did influence the Ordinance of 1787, that prohibited slavery in the Northwest Territory. It would also serve as inspiration and citation for future attempts to restrict slavery's domestic expansion. In 1848, senator David Wilmot cited it while trying to build support for the Wilmot Proviso, which would have banned slavery in territory captured during the Mexican–American War. In 1860, Presidential candidate Abraham Lincoln cited it to make his case that banning slavery in the federal territories was constitutional. But the effect of Jefferson's nearly accomplished plan to ban slavery outright in any new state would have been a huge and likely fatal blow to the institution.

In 1785, Jefferson published his first book, Notes on the State of Virginia. In it, he argued that blacks were inferior to whites and this inferiority could not be explained by their condition of slavery. He also stated that these arguments were not certain (see section on this book below). Jefferson stated emancipation and colonization away from America would be the best policy on how to treat blacks and added a warning about the potential for slave revolutions in the future: "I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his justice cannot sleep for ever: that considering numbers, nature and natural means only, a revolution of the wheel of fortune, an exchange of situation is among possible events: that it may become probable by supernatural interference! The almighty has no attribute which can take side with us in such a contest."

From the 1770s on, Jefferson wrote of supporting gradual emancipation, based on slaves being educated, freed after 18 for women and 21 for men (later he changed this to age 45, when their masters had a return on investment), and transported for resettlement to Africa. All of his life, he supported the concept of colonization of Africa by American freedmen. The historian Peter S. Onuf suggested that, after having children with his slave Sally Hemings, Jefferson may have supported colonization because of concerns for his unacknowledged "shadow family". In addition, Onuf asserts that Jefferson believed at this point that slavery was "equal to tyranny".

The historian David Brion Davis stated that in the years after 1785 and Jefferson's return from Paris, the most notable thing about his position on slavery was his "immense silence". Davis believed that, in addition to having internal conflicts about slavery, Jefferson wanted to keep his personal situation private; for this reason, he chose to back away from working to end or ameliorate slavery.

As U.S. Secretary of State, Jefferson issued in 1795, with President Washington's authorization, $40,000 in emergency relief and 1,000 weapons to French slave owners in Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti) in order to suppress a slave rebellion. President Washington gave the slave owners in Saint Domingue (Haiti) $400,000 as repayment for loans the French had granted to the Americans during the American Revolutionary War.

On September 15, 1800, Virginia governor James Monroe sent a letter to Jefferson, informing him of a narrowly averted slave rebellion by Gabriel Prosser. Ten of the conspirators had already been executed, and Monroe asked Jefferson's advice on what to do with the remaining ones. Jefferson sent a reply on September 20, urging Monroe to deport the remaining rebels rather than execute them. Most notably, Jefferson's letter implied that the rebels had some justification for their rebellion in seeking freedom, stating "The other states & the world at large will for ever condemn us if we indulge a principle of revenge, or go one step beyond absolute necessity. They cannot lose sight of the rights of the two parties, & the object of the unsuccessful one." By the time Monroe received Jefferson's letter, twenty of the conspirators had been executed. Seven more would be executed after Monroe received the letter on September 22, including Prosser himself, but an additional 50 defendants charged for the failed rebellion would be acquitted, pardoned, or have their sentences commuted.

As President (1801–1809)

In 1800, Jefferson was elected as President of the United States over John Adams. He won more electoral votes than Adams, aided by southern power. The Constitution provided for the counting of slaves as three fifths of their total population, to be added to a state's total population for purposes of apportionment and the electoral college. States with large slave populations, therefore, gained greater representation even though the number of voting citizens was smaller than that of other states. It was due only to this population advantage that Jefferson won the election.

Moved slaves to White House

Jefferson brought slaves from Monticello to work at the White House. He brought Edith Hern Fossett and Fanny Hern to Washington, D.C., in 1802 and they learned to cook French cuisine at the President's House by Honoré Julien. Edith was 15 years old and Fanny was 18. Margaret Bayard Smith remarked of the French fare, "The excellence and superior skill of his [Jefferson's] French cook was acknowledged by all who frequented his table, for never before had such dinners been given in the President's House". Edith and Fanny were the only slaves from Monticello to regularly live in Washington. They did not receive a wage, but earned a two-dollar gratuity each month. They worked in Washington for nearly seven years and Edith gave birth to three children while at the President's House, James, Maria, and a child who did not survive to adulthood. Fanny had one child there. Their children were kept with them at the President's House.

Haitian independence

After Toussaint Louverture had become governor general of Saint-Domingue following a slave revolt, in 1801 Jefferson supported French plans to take back the island. He agreed to loan France $300,000 "for relief of whites on the island." Jefferson wanted to alleviate the fears of southern slave owners, who feared a similar rebellion in their territory. Prior to his election, Jefferson wrote of the revolution, "If something is not done and soon, we shall be the murderers of our own children."

By 1802, when Jefferson learned that France was planning to re-establish its empire in the western hemisphere, including taking the Louisiana territory and New Orleans from the Spanish, he declared the neutrality of the US in the Caribbean conflict. While refusing credit or other assistance to the French, he allowed contraband goods and arms to reach Haiti and, thus, indirectly supported the Haitian Revolution. This was to further US interests in Louisiana.

That year and once the Haitians declared independence in 1804, President Jefferson had to deal with strong hostility to the new nation by his southern-dominated Congress. He shared planters' fears that the success of Haiti would encourage similar slave rebellions and widespread violence in the South. Historian Tim Matthewson noted that Jefferson faced a Congress "hostile to Haiti", and that he "acquiesced in southern policy, the embargo of trade and nonrecognition, the defense of slavery internally and the denigration of Haiti abroad." Jefferson discouraged emigration by American free blacks to the new nation. European nations also refused to recognize Haiti when the new nation declared independence in 1804. In his short biography of Jefferson in 2005, Christopher Hitchens noted the president was "counterrevolutionary" in his treatment of Haiti and its revolution.

Jefferson expressed ambivalence about Haiti. During his presidency, he thought sending free blacks and contentious slaves to Haiti might be a solution to some of the United States' problems. He hoped that "Haiti would eventually demonstrate the viability of black self-government and the industriousness of African American work habits, thereby justifying freeing and deporting the slaves" to that island. This was one of his solutions for separating the populations. In 1824, book peddler Samuel Whitcomb, Jr. visited Jefferson in Monticello, and they happened to talk about Haiti. This was on the eve of the greatest emigration of U.S. Blacks to the island-nation. Jefferson told Whitcomb that he had never seen Blacks do well in governing themselves, and thought they would not do it without the help of Whites.

Virginia emancipation law modified

In 1806, with concern developing over the rise in the number of free black people, the Virginia General Assembly modified the 1782 slave law to discourage free black people from living in the state. It permitted re-enslavement of freedmen who remained in the state for more than 12 months. This forced newly freed black people to leave enslaved kin behind. As slaveholders had to petition the legislature directly to gain permission for manumitted freedmen to stay in the state, there was a decline in manumissions after this date.

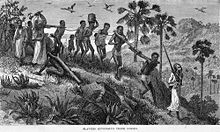

Ended international slave trade

In 1808, Jefferson denounced the international slave trade and called for a law to make it a crime. He told Congress in his 1806 annual message, such a law was needed to "withdraw the citizens of the United States from all further participation in those violations of human rights ... which the morality, the reputation, and the best interests of our country have long been eager to proscribe." Congress complied and on March 2, 1807, Jefferson signed the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves into law; it took effect 1 January 1808 and made it a federal crime to import or export slaves from abroad.

By 1808, every state but South Carolina had followed Virginia's lead from the 1780s in banning importation of slaves. By 1808, with the growth of the domestic slave population enabling development of a large internal slave trade, slaveholders did not mount much resistance to the new law, presumably because the authority of Congress to enact such legislation was expressly authorized by the Constitution, and was fully anticipated during the Constitutional Convention in 1787. The end of international trade also increased the monetary value of existing slaves. Jefferson did not lead the campaign to prohibit the importation of slaves. Historian John Chester Miller rated Jefferson's two major presidential achievements as the Louisiana Purchase and the abolition of the international slave trade.

Retirement (1810–1826)

In 1819, Jefferson strongly opposed a Missouri statehood application amendment that banned domestic slave importation and freed slaves at the age of 25 believing it would destroy or break up the union. By 1820, Jefferson, objected to what he viewed as "Northern meddling" with Southern slavery policy. On April 22, Jefferson criticized the Missouri Compromise because it might lead to the breakup of the Union. Jefferson said slavery was a complex issue and needed to be solved by the next generation. Jefferson wrote that the Missouri Compromise was a "fire bell in the night" and "the knell of the Union". Jefferson said that he feared the Union would dissolve, stating that the "Missouri question aroused and filled me with alarm." In regard to whether the Union would remain for a long period of time Jefferson wrote, "I now doubt it much." In 1823, in a letter to Supreme Court Justice William Johnson, Jefferson wrote "this case is not dead, it only sleepeth. the Indian chief said he did not go to war for every petty injury by itself; but put it into his pouch, and when that was full, he then made war."

In 1798, Jefferson's friend from the Revolution, Tadeusz Kościuszko, a Polish nobleman and revolutionary, visited the United States to collect back pay from the government for his military service. He entrusted his assets to Jefferson with a will directing him to spend the American money and proceeds from his land in the U.S. to free and educate slaves, including Jefferson's, and at no cost to Jefferson. Kościuszko revised will states: "I hereby authorise my friend Thomas Jefferson to employ the whole thereof in purchasing Negroes from among his own or any others and giving them Liberty in my name." Kosciuszko died in 1817, but Jefferson never carried out the terms of the will: At age 77, he pleaded an inability to act as executor due to his advanced age and the numerous legal complexities of the bequest—the will was contested by several family members and was tied up in the courts for years, long after Jefferson's death. Jefferson recommended his friend John Hartwell Cocke, who also opposed slavery, as executor, but Cocke likewise declined to execute the bequest. In 1852 the U.S. Supreme Court awarded the estate, by then worth $50,000, to Kościuszko's heirs in Poland, having ruled that the will was invalid.

Jefferson continued to struggle with debt after serving as president. He used some of his hundreds of slaves as collateral to his creditors. This debt was due to his lavish lifestyle, long construction and changes to Monticello, imported goods, art, and lifelong issues with debt, from inheriting the debt of father-in-law John Wayles to signing two 10,000 notes late in life to assist dear friend Wilson Cary Nicholas, which proved to be his coup de grace. Yet he was merely one of numerous others who suffered crippling debt around 1820. He also incurred debt in helping support his only surviving daughter, Martha Jefferson Randolph, and her large family. She had separated from her husband, who had become abusive from alcoholism and mental illness (according to different sources), and brought her family to live at Monticello.

In August 1814, the planter Edward Coles and Jefferson corresponded about Coles' ideas on emancipation. Jefferson urged Coles not to free his slaves, but the younger man took all his slaves to the Illinois and freed them, providing them with land for farms.

In April 1820, Jefferson wrote to John Holmes giving his thoughts on the Missouri compromise. Concerning slavery, he said:

there is not a man on earth who would sacrifice more than I would, to relieve us from this heavy reproach [slavery] ... we have the wolf by the ear, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.

Jefferson may have borrowed from Suetonius, a Roman biographer, the phrase "wolf by the ears", as he held a book of his works. Jefferson characterized slavery as a dangerous animal (the wolf) that could not be contained or freed. He believed that attempts to end slavery would lead to violence. Jefferson concluded the letter lamenting "I regret that I am now to die in the belief that the useless sacrifice of themselves, by the generation of '76. to acquire self government and happiness to their country, is to be thrown away by the unwise and unworthy passions of their sons, and that my only consolation is to be that I live not to weep over it." Following the Missouri Compromise, Jefferson largely withdrew from politics and public life, writing "with one foot in the grave, I have no right to meddle with these things."

In 1821, Jefferson wrote in his autobiography that he felt slavery would inevitably come to an end, though he also felt there was no hope for racial equality in America, stating "Nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate than that these people [negros] are to be free. Nor is it less certain that the two races, equally free, cannot live in the same government. Nature, habit, opinion has drawn indelible lines of distinction between them. It is still in our power to direct the process of emancipation, and deportation, peaceably, and in such slow degrees, as that the evil will wear off insensibly; and their places be, pari passu, filled up by free white laborers. If, on the contrary, it is left to force itself on, human nature must shudder at the prospect held up."

The U.S. Congress finally implemented colonization of freed African American slaves by passing the Slave Trade Act of 1819 signed into law by President James Monroe. The law authorized funding to colonize the coast of Africa with freed African American slaves. In 1824, Jefferson proposed an overall emancipation plan that would free slaves born after a certain date. Jefferson proposed that African-American children born in America be bought by the federal government for $12.50 and that these slaves be sent to Santo Domingo. Jefferson admitted that his plan would be liberal and may even be unconstitutional, but he suggested a constitutional amendment to allow congress to buy slaves. He also realized that separating children from slaves would have a humanitarian cost. Jefferson believed that his overall plan was worth implementing and that setting over a million slaves free was worth the financial and emotional costs.

Posthumous (1827–1830)

At his death, Jefferson was greatly in debt, in part due to his continued construction program. The debts encumbered his estate, and his family sold 130 slaves, virtually all the members of every slave family, from Monticello to pay his creditors. Slave families who had been well established and stable for decades were sometimes split up. Most of the sold slaves either remained in Virginia or were relocated to Ohio.

Jefferson freed five slaves in his will, all males of the Hemings family. Those were his two natural sons, and Sally's younger half-brother John Hemings, and her nephews Joseph (Joe) Fossett and Burwell Colbert. He gave Burwell Colbert, who had served as his butler and valet, $300 for purchasing supplies used in the trade of "painter and glazier". He gave John Hemings and Joe Fossett each an acre on his land so they could build homes for their families. His will included a petition to the state legislature to allow the freedmen to remain in Virginia to be with their families, who remained enslaved under Jefferson's heirs.

Jefferson freed Joseph Fossett in his will, but Fossett's wife (Edith Hern Fossett) and their eight children were sold at auction. Fossett was able to get enough money to buy the freedom of his wife and two youngest children. The remainder of their ten children were sold to different slaveholders. The Fossetts worked for 23 years to purchase the freedom of their remaining children.

Born and reared as free, not knowing that I was a slave, then suddenly, at the death of Jefferson, put upon an auction block and sold to strangers.

In 1827, the auction of 130 slaves took place at Monticello. The sale lasted for five days despite the cold weather. The slaves brought prices over 70% of their appraised value. Within three years, all of the "black" families at Monticello had been sold and dispersed.

Sally Hemings and her children

For two centuries the claim that Thomas Jefferson fathered children by his slave, Sally Hemings, has been a matter of discussion and disagreement. In 1802, the journalist James T. Callender, after being denied a position as postmaster by Jefferson, published allegations that Jefferson had taken Hemings as a concubine and had fathered several children with her. John Wayles held her as a slave, and was also her father, as well as the father of Jefferson's wife Martha. Sally was three-quarters white and strikingly similar in looks and voice to Jefferson's late wife.

In 1998, in order to establish the male DNA line, a panel of researchers conducted a Y-DNA study of living descendants of Jefferson's uncle, Field, and of a descendant of Sally's son, Eston Hemings. The results, published in the journal Nature, showed a Y-DNA match with the male Jefferson line. In 2000, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation (TJF) assembled a team of historians whose report concluded that, together with the DNA and historic evidence, there was a high probability that Jefferson was the father of Eston and likely of all Hemings' children. W. M. Wallenborn, who worked on the Monticello report, disagreed, claiming the committee had already made up their minds before evaluating the evidence, was a "rush to judgement", and that the claims of Jefferson's paternity were unsubstantiated and politically driven.

Since the DNA tests were made public, most biographers and historians have concluded that the widower Jefferson had a long-term relationship with Hemings, and fathered at least some and probably all of her children. A minority of scholars, including a team of professors associated with the Thomas Jefferson Heritage Society, maintain that the evidence is insufficient to conclude Thomas Jefferson's paternity, and note the possibility that other Jeffersons, including Thomas's brother Randolph Jefferson and his five sons, who were alleged to have raped enslaved women, could have fathered Hemings' children. Jefferson allowed two of Sally's children to leave Monticello without formal manumission when they came of age; five other slaves, including the two remaining sons of Sally, were freed by his will upon his death. Although not legally freed, Sally left Monticello with her sons. They were counted as free whites in the 1830 census. Madison Hemings, in an article titled, "Life Among the Lowly", in small Ohio newspaper called Pike County Republican, claimed that Jefferson was his father.

Monticello slave life

Jefferson ran every facet of the four Monticello farms and left specific instructions to his overseers when away or traveling. Slaves in the mansion, mill, and nailery reported to one general overseer appointed by Jefferson, and he hired many overseers, some of whom were considered cruel at the time. Jefferson made meticulous periodical records on his slaves, plants and animals, and weather. Jefferson, in his Farm Book journal, visually described in detail both the quality and quantity of purchased slave clothing and the names of all slaves who received the clothing. In a letter written in 1811, Jefferson described his stress and apprehension in regard to difficulties in what he felt was his "duty" to procure specific desirable blankets for "those poor creatures" – his slaves.

Some historians have noted that Jefferson maintained many slave families together on his plantations; historian Bruce Fehn says this was consistent with other slave owners at the time. There were often more than one generation of family at the plantation and families were stable. Jefferson and other slaveholders shifted the "cost of reproducing the workforce to the workers' themselves". He could increase the value of his property without having to buy additional slaves. He tried to reduce infant mortality, and wrote, "[A] woman who brings a child every two years is more profitable than the best man on the farm."

Jefferson encouraged the enslaved at Monticello to "marry". (The enslaved could not marry legally in Virginia.) He would occasionally buy and sell slaves to keep families together. In 1815, he said that his slaves were "worth a great deal more" due to their marriages. "Married" slaves, however, had no legal protection or recognition under the law; masters could separate slave "husbands" and "wives" at will.

Thomas Jefferson recorded his strategy for employing children in his Farm Book. Until the age of 10, children served as nurses. When the plantation grew tobacco, children were at a good height to remove and kill tobacco worms from the crops. Once he began growing wheat, fewer people were needed to maintain the crops, so Jefferson established manual trades. He stated that children "go into the ground or learn trades." When girls were 16, they began spinning and weaving textiles. Boys made nails from age 10 to 16. In 1794, Jefferson had a dozen boys working at the nailery. The nail factory was on Mulberry Row. After it opened in 1794, for the first three years, Jefferson recorded the productivity of each child. He selected those who were most productive to be trained as artisans: blacksmiths, carpenters, and coopers. Those who performed the worst were assigned as field laborers. While working at the nailery, boys received more food and may have received new clothes if they did a good job.

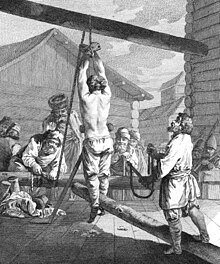

James Hubbard was an enslaved worker in the nailery who ran away on two occasions. The first time Jefferson did not have him whipped, but on the second Jefferson reportedly ordered him severely flogged. Hubbard was likely sold after spending time in jail. Stanton says children suffered physical violence. When a 17-year-old James was sick, one overseer reportedly whipped him "three times in one day". Violence was commonplace on plantations, including Jefferson's. Henry Wiencek cited within a Smithsonian Magazine article several reports of Jefferson ordering the whipping or selling of slaves as punishments for extreme misbehavior or escape.

The Thomas Jefferson Foundation quotes Jefferson's instructions to his overseers not to whip his slaves, but noted that they often ignored his wishes during his frequent absences from home. According to Stanton, no reliable document portrays Jefferson as directly using physical correction. During Jefferson's time, some other slaveholders also disagreed with the practices of flogging and jailing slaves.

Slaves had a variety of tasks: Davy Bowles was the carriage driver, including trips to take Jefferson to and from Washington D.C. or the Virginia capital. Betty Hemings, a mixed-race slave inherited from his father-in-law with her family, was the matriarch and head of the house slaves at Monticello, who were allowed limited freedom when Jefferson was away. Four of her daughters served as house slaves: Betty Brown; Nance, Critta and Sally Hemings. The latter two were half-sisters to Jefferson's wife, and Sally bore him 6 children. Another house slave was Ursula Granger, whom he had purchased separately. The general maintenance of the mansion was under the care of Hemings family members as well: the master carpenter was Betty's son John Hemings. His nephews Joe Fossett, as blacksmith, and Burwell Colbert, as Jefferson's butler and painter, also had important roles. Wormley Hughes, a grandson of Betty Hemings and gardener, was given informal freedom after Jefferson's death. Memoirs of life at Monticello include those of Isaac Jefferson (published, 1843), Madison Hemings, and Israel Jefferson (both published, 1873). Isaac was an enslaved blacksmith who worked on Jefferson's plantation.

The last surviving recorded interview of a former slave was with Fountain Hughes, then 101, in Baltimore, Maryland in 1949. It is available online at the Library of Congress and the World Digital Library. Born in Charlottesville, Fountain was a descendant of Wormley Hughes and Ursula Granger; his grandparents were among the house slaves owned by Jefferson at Monticello.

Notes on the State of Virginia (1785)

In 1780, Jefferson began answering questions on the colonies asked by French minister François de Marboias. He worked on what became a book for five years, having it printed in France while he was there as U.S. minister in 1785. The book covered subjects such as mountains, religion, climate, slavery, and race.

Views on race

In Query XIV of his Notes, Jefferson analyses the nature of Blacks. He stated that Blacks lacked forethought, intelligence, tenderness, grief, imagination, and beauty; that they had poor taste, smelled bad, and were incapable of producing artistry or poetry; but conceded that they were the moral equals of all others. Jefferson believed that the bonds of love for blacks were weaker than those for whites. Jefferson never settled on whether differences were natural or nurtural, but he stated unquestionably that his views ought to be taken cum grano salis;

The opinion, that they are inferior in the faculties of reason and imagination, must be hazarded with great diffidence. To justify a general conclusion, requires many observations, even where the subject may be submitted to the Anatomical knife, to Optical glasses, to analysis by fire or by solvents. How much more then where it is a faculty, not a substance, we are examining; where it eludes the research of all the senses; where the conditions of its existence are various and variously combined; where the effects of those which are present or absent bid defiance to calculation; let me add too, as a circumstance of great tenderness, where our conclusion would degrade a whole race of men from the rank in the scale of beings which their Creator may perhaps have given them. To our reproach it must be said, that though for a century and a half we have had under our eyes the races of black and of red men, they have never yet been viewed by us as subjects of natural history. I advance it, therefore, as a suspicion only, that the blacks, whether originally a distinct race, or made distinct by time and circumstances, are inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind. It is not against experience to suppose that different species of the same genus, or varieties of the same species, may possess different qualifications.

In 1808, French abolitionist Henri Grégoire sent Jefferson a copy of his book, An Enquiry Concerning the Intellectual and Moral Faculties and Literature of Negroes. In the book, Grégoire responded to and challenged Jefferson's arguments of Black inferiority in Notes on the State of Virginia by citing the advanced civilizations Africans had developed as evidence of their intellectual competence. Jefferson replied to Grégoire that the rights of African Americans should not depend on intelligence and that Black people had "respectable intelligence". Jefferson wrote of Black people that,

but whatever be their degree of talent it is no measure of their rights. Because Sir Isaac Newton was superior to others in understanding, he was not therefore lord of the person or property of others. On this subject they are gaining daily in the opinions of nations, and hopeful advances are making towards their re-establishment on an equal footing with the other colors of the human family.

Dumas Malone, Jefferson's biographer, explained Jefferson's contemporary views on race as expressed in Notes were the "tentative judgements of a kindly and scientifically minded man". Merrill Peterson, another Jefferson biographer, claimed Jefferson's racial bias against African Americans was "a product of frivolous and tortuous reasoning ... and bewildering confusion of principles." Peterson called Jefferson's racial views on African Americans "folk belief".

In a reply (in The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 10, 22 June-31 December 1786, ed. Julian P. Boyd p. 20-29) to Jean Nicolas DeMeunier's inquiries concerning the Paris publication of his Notes On The State of Virginia (1785) Jefferson described the Southern slave plantation economy as "a species of property annexed to certain mercantile houses in London": "Virginia certainly owed two millions sterling to Great Britain at the conclusion of the [Revolutionary] war. ... This is to be ascribed to peculiarities in the tobacco trade. The advantages [profits] made by the British merchants on the tobaccoes consigned to them were so enormous that they spared no means of increasing those consignments. A powerful engine for this purpose was the giving good prices and credit to the planter, till they got him more immersed in debt than he could pay without selling his lands or slaves. They then reduced the prices given for his tobacco so that let his shipments be ever so great, and his demand of necessaries ever so economical, they never permitted him to clear off his debt. These debts had become hereditary from father to son for many generations, so that the planters were a species of property annexed to certain mercantile houses in London." After the Revolution this subjection of the Southern plantation economy to absentee finance, commodities brokers, import-export merchants and wholesalers continued, with the center of finance and trade shifting from London to Manhattan where, up until the Civil War, banks continued to write mortgages with slaves as collateral, and foreclose on plantations in default and operate them in their investors' interests, as discussed by Philip S. Foner.

Support for colonization plan

In his Notes Jefferson wrote of a plan he supported in 1779 in the Virginia legislature that would end slavery through the colonization of freed slaves. This plan was widely popular among the French people in 1785 who lauded Jefferson as a philosopher. According to Jefferson, this plan required enslaved adults to continue in slavery but their children would be taken from them and trained to have a skill in the arts or sciences. These skilled women at age 18 and men at 21 would be emancipated, given arms and supplies, and sent to colonize a foreign land. Jefferson believed that colonization was the practical alternative, while freed blacks living in a white American society would lead to a race war:

It will probably be asked, Why not retain and incorporate the blacks into the state, and thus save the expense of supplying, by importation of white settlers, the vacancies they will leave? Deep rooted prejudices entertained by the whites; ten thousand recollections, by the blacks, of the injuries they have sustained; new provocations; the real distinctions which nature has made; and many other circumstances, will divide us into parties, and produce convulsions which will probably never end but in the extermination of the one or the other race.

Criticism for effects of slavery

In Notes Jefferson criticized the effects slavery had on both white and African-American slave society. He writes:

There must doubtless be an unhappy influence on the manners of our people produced by the existence of slavery among us. The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other. Our children see this, and learn to imitate it; for man is an imitative animal. This quality is the germ of all education in him. From his cradle to his grave he is learning to do what he sees others do. If a parent could find no motive either in his philanthropy or his self-love, for restraining the intemperance of passion towards his slave, it should always be a sufficient one that his child is present. But generally it is not sufficient. The parent storms, the child looks on, catches the lineaments of wrath, puts on the same airs in the circle of smaller slaves, gives a loose to his worst of passions, and thus nursed, educated, and daily exercised in tyranny, cannot but be stamped by it with odious peculiarities. The man must be a prodigy who can retain his manners and morals undepraved by such circumstances. And with what execration should the statesman be loaded, who permitting one half the citizens thus to trample on the rights of the other, transforms those into despots, and these into enemies, destroys the morals of the one part, and the amor patriae of the other.

Evaluations by historians

According to James W. Loewen, Jefferson's character "wrestled with slavery, even though in the end he lost." Loewen says that understanding Jefferson's relationship with slavery is significant in understanding current American social problems.

Important 20th-century Jefferson biographers including Merrill Peterson support the view that Jefferson was strongly opposed to slavery; Peterson said that Jefferson's ownership of slaves "all his adult life has placed him at odds with his moral and political principles. Yet there can be no question of his genuine hatred of slavery or, indeed, of the efforts he made to curb and eliminate it." Peter Onuf stated that Jefferson was well known for his "opposition to slavery, most famously expressed in his ... Notes on the State of Virginia." Onuf, and his collaborator Ari Helo, inferred from Jefferson's words and actions that he was against the cohabitation of free blacks and whites. This, they argued, is what made immediate emancipation so problematic in Jefferson's mind. As Onuf and Helo explained, Jefferson opposed the mixing of the races not because of his belief that blacks were inferior (although he did provisionally believe this) but because he feared that instantly freeing the slaves in white territory would trigger "genocidal violence". He could not imagine the blacks living in harmony with their former oppressors. Jefferson was sure that the two races would be in constant conflict. Onuf and Helo asserted that Jefferson was, consequently, a proponent of freeing the Africans through "expulsion", which he thought would have ensured the safety of both the whites and blacks. Biographer John Ferling said that Thomas Jefferson was "zealously committed to slavery's abolition".

Starting in the early 1960s, some academics began to challenge Jefferson's position as an anti-slavery advocate having reevaluated both his actions and his words. Paul Finkelman wrote in 1994 that earlier scholars, particularly Peterson, Dumas Malone, and Willard Randall, engaged in "exaggeration or misrepresentation" to advance their argument of Jefferson's anti-slavery position, saying "they ignore contrary evidence" and "paint a false picture" to protect Jefferson's image on slavery.

In 2012, author Henry Wiencek, highly critical of Jefferson, concluded that Jefferson tried to protect his legacy as a Founding Father by hiding slavery from visitors at Monticello and through his writings to abolitionists. According to Wiencek's view Jefferson made a new frontage road to his Monticello estate to hide the overseers and slaves who worked the agriculture fields. Wiencek believed that Jefferson's "soft answers" to abolitionists were to make himself appear opposed to slavery. Wiencek stated that Jefferson held enormous political power but "did nothing to hasten slavery's end during his terms as a diplomat, secretary of state, vice president, and twice-elected president or after his presidency."

According to Greg Warnusz, Jefferson held typical 19th-century beliefs that blacks were inferior to whites in terms of "potential for citizenship", and he wanted them recolonized to independent Liberia and other colonies. His views of a democratic society were based on a homogeneity of white working men. He claimed to be interested in helping both races in his proposal. He proposed gradually freeing slaves after the age of 45 (when they would have repaid their owner's investment) and resettling them in Africa. (This proposal did not acknowledge how difficult it would be for freedmen to be settled in another country and environment after age 45.) Jefferson's plan envisioned a whites-only society without any blacks.

Concerning Jefferson and race, author Annette Gordon-Reed stated the following:

Of all the Founding Fathers, it was Thomas Jefferson for whom the issue of race loomed largest. In the roles of slaveholder, public official and family man, the relationship between blacks and whites was something he thought about, wrote about and grappled with from his cradle to his grave.

Paul Finkelman claims that Jefferson believed that Blacks lacked basic human emotions.

According to historian Jeremy J. Tewell, although Jefferson's name had been associated with the anti-slavery cause during the early 1770s in the Virginia legislature, Jefferson viewed slavery as a "Southern way of life", similar to mainstream Greek and antiquity societies. In agreement with the Southern slave society, Tewell says Jefferson believed that slavery served to protect blacks, whom he viewed as inferior or incapable of taking care of themselves.

According to Joyce Appleby, Jefferson had opportunities to disassociate himself from slavery. In 1782, after the American Revolution, Virginia passed a law making manumission by the slave owner legal and more easily accomplished, and the manumission rate rose across the Upper South in other states as well. Northern states passed various emancipation plans. Jefferson's actions did not keep up with those of the antislavery advocates. On September 15, 1793, Jefferson agreed in writing to free James Hemings, his mixed-race slave who had served him as chef since their time in Paris, after the slave had trained his younger brother Peter as a replacement chef. Jefferson finally freed James Hemings in February 1796. According to one historian, Jefferson's manumission was not generous; he said the document "undermines any notion of benevolence." With freedom, Hemings worked in Philadelphia and traveled to France.

In contrast, a sufficient number of other slaveholders in Virginia freed slaves in the first two decades after the Revolution so that the proportion of free blacks in Virginia compared to the total black population rose from less than 1% in 1790 to 7.2% in 1810.