Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold economically liberal positions, while economic nationalist and left-wing political parties generally support protectionism, the opposite of free trade.

Most nations are today members of the World Trade Organization multilateral trade agreements. Free trade was best exemplified by the unilateral stance of Great Britain who reduced regulations and duties on imports and exports from the mid-nineteenth century to the 1920s. An alternative approach, of creating free trade areas between groups of countries by agreement, such as that of the European Economic Area and the Mercosur open markets, creates a protectionist barrier between that free trade area and the rest of the world. Most governments still impose some protectionist policies that are intended to support local employment, such as applying tariffs to imports or subsidies to exports. Governments may also restrict free trade to limit exports of natural resources. Other barriers that may hinder trade include import quotas, taxes and non-tariff barriers, such as regulatory legislation.

Historically, openness to free trade substantially increased from 1815 to the outbreak of World War I. Trade openness increased again during the 1920s, but collapsed (in particular in Europe and North America) during the Great Depression. Trade openness increased substantially again from the 1950s onwards (albeit with a slowdown during the 1973 oil crisis). Economists and economic historians contend that current levels of trade openness are the highest they have ever been.

Economists are generally supportive of free trade. There is a broad consensus among economists that protectionism has a negative effect on economic growth and economic welfare while free trade and the reduction of trade barriers has a positive effect on economic growth and economic stability. However, in the short run, liberalization of trade can cause significant and unequally distributed losses and the economic dislocation of workers in import-competing sectors.

Features

- Trade of goods without taxes (including tariffs) or other trade barriers (e.g., quotas on imports or subsidies for producers).

- Trade in services without taxes or other trade barriers.

- The absence of "trade-distorting" policies (such as taxes, subsidies, regulations, or laws) that give some firms, households, or factors of production an advantage over others.

- Unregulated access to markets.

- Unregulated access to market information.

- Inability of firms to distort markets through government-imposed monopoly or oligopoly power.

- Trade agreements which encourage free trade.

Economics

Economic models

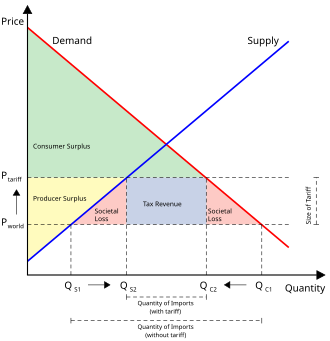

Two simple ways to understand the proposed benefits of free trade are through David Ricardo's theory of comparative advantage and by analyzing the impact of a tariff or import quota. An economic analysis using the law of supply and demand and the economic effects of a tax can be used to show the theoretical benefits and disadvantages of free trade.

Most economists would recommend that even developing nations should set their tariff rates quite low, but the economist Ha-Joon Chang, a proponent of industrial policy, believes higher levels may be justified in developing nations because the productivity gap between them and developed nations today is much higher than what developed nations faced when they were at a similar level of technological development. Underdeveloped nations today, Chang believes, are weak players in a much more competitive system. Counterarguments to Chang's point of view are that the developing countries are able to adopt technologies from abroad whereas developed nations had to create new technologies themselves and that developing countries can sell to export markets far richer than any that existed in the 19th century.

If the chief justification for a tariff is to stimulate infant industries, it must be high enough to allow domestic manufactured goods to compete with imported goods in order to be successful. This theory, known as import substitution industrialization, is largely considered ineffective for currently developing nations.

Tariffs

The chart at the right analyzes the effect of the imposition of an import tariff on some imaginary good. Prior to the tariff, the price of the good in the world market and hence in the domestic market is Pworld. The tariff increases the domestic price to Ptariff. The higher price causes domestic production to increase from QS1 to QS2 and causes domestic consumption to decline from QC1 to QC2.

This has three effects on societal welfare. Consumers are made worse off because the consumer surplus (green region) becomes smaller. Producers are better off because the producer surplus (yellow region) is made larger. The government also has additional tax revenue (blue region). However, the loss to consumers is greater than the gains by producers and the government. The magnitude of this societal loss is shown by the two pink triangles. Removing the tariff and having free trade would be a net gain for society.

An almost identical analysis of this tariff from the perspective of a net producing country yields parallel results. From that country's perspective, the tariff leaves producers worse off and consumers better off, but the net loss to producers is larger than the benefit to consumers (there is no tax revenue in this case because the country being analyzed is not collecting the tariff). Under similar analysis, export tariffs, import quotas and export quotas all yield nearly identical results.

Sometimes consumers are better off and producers worse off and sometimes consumers are worse off and producers are better off, but the imposition of trade restrictions causes a net loss to society because the losses from trade restrictions are larger than the gains from trade restrictions. Free trade creates winners and losers, but theory and empirical evidence show that the gains from free trade are larger than the losses.

A 2021 study found that across 151 countries over the period 1963–2014, "tariff increases are associated with persistent, economically and statistically significant declines in domestic output and productivity, as well as higher unemployment and inequality, real exchange rate appreciation, and insignificant changes to the trade balance."

Technology and innovation

Economic models indicate that free trade leads to greater technology adoption and innovation.

Productivity and welfare

A 2023 study in Journal of Political Economy found that reductions in trade costs since 1980 caused increases in agricultural productivity, food consumption and welfare across the world. The welfare gains were particularly large in some developing countries.

Trade diversion

According to mainstream economics theory, the selective application of free trade agreements to some countries and tariffs on others can lead to economic inefficiency through the process of trade diversion. It is efficient for a good to be produced by the country which is the lowest cost producer, but this does not always take place if a high cost producer has a free trade agreement while the low cost producer faces a high tariff. Applying free trade to the high cost producer and not the low cost producer as well can lead to trade diversion and a net economic loss. This reason is why many economists place such high importance on negotiations for global tariff reductions, such as the Doha Round.

Opinions

Economist opinions

The literature analysing the economics of free trade is rich. Economists have done extensive work on the theoretical and empirical effects of free trade. Although it creates winners and losers, the broad consensus among economists is that free trade provides a net gain for society. In a 2006 survey of American economists (83 responders), "87.5% agree that the U.S. should eliminate remaining tariffs and other barriers to trade" and "90.1% disagree with the suggestion that the U.S. should restrict employers from outsourcing work to foreign countries".

Quoting Harvard economics professor N. Gregory Mankiw, "Few propositions command as much consensus among professional economists as that open world trade increases economic growth and raises living standards". In a survey of leading economists, none disagreed with the notion that "freer trade improves productive efficiency and offers consumers better choices, and in the long run these gains are much larger than any effects on employment".

Paul Krugman stated that free trade is greatly beneficial to the world as a whole, and especially beneficial to people in poorer nations, since it allows them to increase their standards of living. He also stated in 2007 that as the US trades more with less-industrialized countries whose workers are paid less than equivalent US workers (2007 wages in Mexico were 1/10th what they were in the US, and in China less than 1/20th), that increased trade with those countries will put downward pressure on unskilled labor rates in the US.

Public opinions

An overwhelming number of people internationally – both in developed and developing countries – support trade with other countries, but are more split when it comes to whether or not they believe trade creates jobs, increases wages, and decreases prices. The median belief in advanced economies is that trade increases wages, with 31 percent of people believing it does, compared to 27 percent who believe it does not. In emerging economies, 47 percent of people believe trade increases wages, compared to 20 percent who says it lowers wages. There is a positive relationship of 0.66 between the average GDP growth rate for the years 2014 to 2017 and the percentage of people in a given country that say trade increases wages. Most people, in both advanced and emerging economies, believe that trade increases prices. 35 percent of people in advanced economies and 56 percent in emerging economies believe trade increases prices, and 29 percent and 18 percent, respectively, believe that trade lowers prices. Those with a higher level of education are more likely than those with less education to believe that trade lowers prices.

History

Early era

The notion of a free trade system encompassing multiple sovereign states originated in a rudimentary form in 16th century Imperial Spain. American jurist Arthur Nussbaum noted that Spanish theologian Francisco de Vitoria was "the first to set forth the notions (though not the terms) of freedom of commerce and freedom of the seas". Vitoria made the case under principles of jus gentium. However, it was two early British economists Adam Smith and David Ricardo who later developed the idea of free trade into its modern and recognizable form.

Economists who advocated free trade believed trade was the reason why certain civilizations prospered economically. For example, Smith pointed to increased trading as being the reason for the flourishing of not just Mediterranean cultures such as Egypt, Greece and Rome, but also of Bengal (East India) and China. Netherlands prospered greatly after throwing off Spanish Imperial rule and pursuing a policy of free trade. This made the free trade/mercantilist dispute the most important question in economics for centuries. Free trade policies have battled with mercantilist, protectionist, isolationist, socialist, populist and other policies over the centuries.

The Ottoman Empire had liberal free trade policies by the 18th century, with origins in capitulations of the Ottoman Empire, dating back to the first commercial treaties signed with France in 1536 and taken further with capitulations in 1673, in 1740 which lowered duties to only 3% for imports and exports and in 1790. Ottoman free trade policies were praised by British economists advocating free trade such as J. R. McCulloch in his Dictionary of Commerce (1834), but criticized by British politicians opposing free trade such as Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, who cited the Ottoman Empire as "an instance of the injury done by unrestrained competition" in the 1846 Corn Laws debate, arguing that it destroyed what had been "some of the finest manufactures of the world" in 1812.

Trade in colonial America was regulated by the British mercantile system through the Acts of Trade and Navigation. Until the 1760s, few colonists openly advocated for free trade, in part because regulations were not strictly enforced (New England was famous for smuggling), but also because colonial merchants did not want to compete with foreign goods and shipping. According to historian Oliver Dickerson, a desire for free trade was not one of the causes of the American Revolution. "The idea that the basic mercantile practices of the eighteenth century were wrong", wrote Dickerson, "was not a part of the thinking of the Revolutionary leaders".

Free trade came to what would become the United States as a result of the American Revolution. After the British Parliament issued the Prohibitory Act in 1775, blockading colonial ports, the Continental Congress responded by effectively declaring economic independence, opening American ports to foreign trade on 6 April 1776 – three months before declaring sovereign independence. According to historian John W. Tyler, "[f]ree trade had been forced on the Americans, like it or not".

In March 1801, the Pope Pius VII ordered some liberalization of trade to face the economic crisis in the Papal States with the motu proprio Le più colte. Despite this, the export of national corn was forbidden to ensure the food for the Papal States.

In Britain, free trade became a central principle practiced by the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846. Large-scale agitation was sponsored by the Anti-Corn Law League. Under the Treaty of Nanking, China opened five treaty ports to world trade in 1843. The first free trade agreement, the Cobden-Chevalier Treaty, was put in place in 1860 between Britain and France which led to successive agreements between other countries in Europe.

Many classical liberals, especially in 19th and early 20th century Britain (e.g. John Stuart Mill) and in the United States for much of the 20th century (e.g. Henry Ford and Secretary of State Cordell Hull), believed that free trade promoted peace. Woodrow Wilson included free-trade rhetoric in his "Fourteen Points" speech of 1918:

The program of the world's peace, therefore, is our program; and that program, the only possible program, all we see it, is this: [...] 3. The removal, so far as possible, of all economic barriers and the establishment of equality of trade conditions among all the nations consenting to the peace and associating themselves for its maintenance.

According to economic historian Douglas Irwin, a common myth about United States trade policy is that low tariffs harmed American manufacturers in the early 19th century and then that high tariffs made the United States into a great industrial power in the late 19th century. A review by the Economist of Irwin's 2017 book Clashing over Commerce: A History of US Trade Policy notes:

Political dynamics would lead people to see a link between tariffs and the economic cycle that was not there. A boom would generate enough revenue for tariffs to fall, and when the bust came pressure would build to raise them again. By the time that happened, the economy would be recovering, giving the impression that tariff cuts caused the crash and the reverse generated the recovery. Mr Irwin also methodically debunks the idea that protectionism made America a great industrial power, a notion believed by some to offer lessons for developing countries today. As its share of global manufacturing powered from 23% in 1870 to 36% in 1913, the admittedly high tariffs of the time came with a cost, estimated at around 0.5% of GDP in the mid-1870s. In some industries, they might have sped up development by a few years. But American growth during its protectionist period was more to do with its abundant resources and openness to people and ideas.

According to Paul Bairoch, since the end of the 18th century, the United States has been "the homeland and bastion of modern protectionism". In fact, the United States never adhered to free trade until 1945. For the most part, the Jeffersonians strongly opposed protectionism. In the 19th century, statesmen such as Senator Henry Clay continued Alexander Hamilton's themes within the Whig Party under the name American System. The opposition Democratic Party contested several elections throughout the 1830s, 1840s and 1850s in part over the issue of the tariff and protection of industry. The Democratic Party favored moderate tariffs used for government revenue only while the Whigs favored higher protective tariffs to protect favored industries. The economist Henry Charles Carey became a leading proponent of the American System of economics. This mercantilist American System was opposed by the Democratic Party of Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren, John Tyler, James K. Polk, Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan.

The fledgling Republican Party led by Abraham Lincoln, who called himself a "Henry Clay tariff Whig", strongly opposed free trade and implemented a 44% tariff during the Civil War, in part to pay for railroad subsidies and for the war effort and in part to protect favored industries. William McKinley (later to become President of the United States) stated the stance of the Republican Party (which won every election for president from 1868 until 1912, except the two non-consecutive terms of Grover Cleveland) as thus:

Under free trade the trader is the master and the producer the slave. Protection is but the law of nature, the law of self-preservation, of self-development, of securing the highest and best destiny of the race of man. [It is said] that protection is immoral [...]. Why, if protection builds up and elevates 63,000,000 [the U.S. population] of people, the influence of those 63,000,000 of people elevates the rest of the world. We cannot take a step in the pathway of progress without benefitting mankind everywhere. Well, they say, 'Buy where you can buy the cheapest'…. Of course, that applies to labor as to everything else. Let me give you a maxim that is a thousand times better than that, and it is the protection maxim: 'Buy where you can pay the easiest.' And that spot of earth is where labor wins its highest rewards.

During the interwar period, economic protectionism took hold in the United States, most famously in the form of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act which is credited by economists with the prolonging and worldwide propagation of the Great Depression. From 1934, trade liberalization began to take place through the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act.

Post-World War II

Since the end of World War II, in part due to industrial size and the onset of the Cold War, the United States has often been a proponent of reduced tariff-barriers and free trade. The United States helped establish the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and later the World Trade Organization, although it had rejected an earlier version in the 1950s, the International Trade Organization. Since the 1970s, United States governments have negotiated managed-trade agreements, such as the North American Free Trade Agreement in the 1990s, and the Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement in 2006.

In Europe, six countries formed the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951 which became the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1958. Two core objectives of the EEC were the development of a common market, subsequently renamed the single market, and establishing a customs union between its member states. After expanding its membership, the EEC became the European Union in 1993. The European Union, now the world's largest single market, has concluded free trade agreements with many countries around the world.

Modern era

Most countries in the world are members of the World Trade Organization which limits in certain ways but does not eliminate tariffs and other trade barriers. Most countries are also members of regional free trade areas that lower trade barriers among participating countries. The European Union and the United States are negotiating a Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership. in 2018, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership came into force, which includes eleven countries that have borders on the Pacific Ocean.

Degree of free trade policies

Free trade may apply to trade in goods and services. Non-economic considerations may inhibit free trade as a country may espouse free trade in principle but ban certain drugs, such as ethanol, or certain practices, such as prostitution, and limiting international free trade.

Some degree of protectionism is nevertheless the norm throughout the world. From 1820 to 1980, the average tariffs on manufactures in twelve industrial countries ranged from 11 to 32%. In the developing world, average tariffs on manufactured goods are approximately 34%. The American economist C. Fred Bergsten devised the bicycle theory to describe trade policy. According to this model, trade policy is dynamically unstable in that it constantly tends towards either liberalisation or protectionism. To prevent falling off the bike (the disadvantages of protectionism), trade policy and multilateral trade negotiations must constantly pedal towards greater liberalisation. To achieve greater liberalisation, decision makers must appeal to the greater welfare for consumers and the wider national economy over narrower parochial interests. However, Bergsten also posits that it is also necessary to compensate the losers in trade and help them find new work as this will both reduce the backlash against globalisation and the motives for trades unions and politicians to call for protection of trade.

In Kicking Away the Ladder, development economist Ha-Joon Chang reviews the history of free trade policies and economic growth and notes that many of the now-industrialized countries had significant barriers to trade throughout their history. The United States and Britain, sometimes considered the homes of free trade policy, employed protectionism to varying degrees at all times. Britain abolished the Corn Laws which restricted import of grain in 1846 in response to domestic pressures and reduced protectionism for manufactures only in the mid 19th century when its technological advantage was at its height, but tariffs on manufactured products had returned to 23% by 1950. The United States maintained weighted average tariffs on manufactured products of approximately 40–50% up until the 1950s, augmented by the natural protectionism of high transportation costs in the 19th century. The most consistent practitioners of free trade have been Switzerland, the Netherlands and to a lesser degree Belgium. Chang describes the export-oriented industrialization policies of the Four Asian Tigers as "far more sophisticated and fine-tuned than their historical equivalents".

Free trade in goods

The Global Enabling Trade Report measures the factors, policies and services that facilitate the trade in goods across borders and to destinations. The index summarizes four sub-indexes, namely market access; border administration; transport and communications infrastructure; and business environment. As of 2016, the top 30 countries and areas were the following:

Singapore 6.0

Singapore 6.0 Netherlands 5.7

Netherlands 5.7 Hong Kong 5.7

Hong Kong 5.7 Luxembourg 5.6

Luxembourg 5.6 Sweden 5.6

Sweden 5.6 Finland 5.6

Finland 5.6 Austria 5.5

Austria 5.5 United Kingdom 5.5

United Kingdom 5.5 Germany 5.5

Germany 5.5 Belgium 5.5

Belgium 5.5 Switzerland 5.4

Switzerland 5.4 Denmark 5.4

Denmark 5.4 France 5.4

France 5.4 Estonia 5.3

Estonia 5.3 Spain 5.3

Spain 5.3 Japan 5.3

Japan 5.3 Norway 5.3

Norway 5.3 New Zealand 5.3

New Zealand 5.3 Iceland 5.3

Iceland 5.3 Ireland 5.3

Ireland 5.3 Chile 5.3

Chile 5.3 United States 5.2

United States 5.2 United Arab Emirates 5.2

United Arab Emirates 5.2 Canada 5.2

Canada 5.2 Czech Republic 5.1

Czech Republic 5.1 Australia 5.1

Australia 5.1 South Korea 5.0

South Korea 5.0 Portugal 5.0

Portugal 5.0 Lithuania 5.0

Lithuania 5.0 Israel 5.0

Israel 5.0

Politics

Academics, governments and interest groups debate the relative costs, benefits and beneficiaries of free trade.

Arguments for protectionism fall into the economic category (trade hurts the economy or groups in the economy) or into the moral category (the effects of trade might help the economy but have ill effects in other areas). A general argument against free trade is that it represents neocolonialism in disguise. The moral category is wide, including concerns about:

- destroying infant industries

- undermining long-run economic development

- promoting income inequality

- tolerating environmental degradation

- supporting child labor and sweatshops

- creating a race to the bottom

- accentuating poverty in poor countries

- harming national defense

- forcing cultural change

Economic arguments against free trade criticize the assumptions or conclusions of economic theories.

Domestic industries often oppose free trade on the grounds that it would lower prices for imported goods would reduce their profits and market share. For example, if the United States reduced tariffs on imported sugar, sugar producers would receive lower prices and profits, and sugar consumers would spend less for the same amount of sugar because of those same lower prices. The economic theory of David Ricardo holds that consumers would necessarily gain more than producers would lose. Since each of the domestic sugar producers would lose a lot while each of a great number of consumers would gain only a little, domestic producers are more likely to mobilize against the reduction in tariffs. More generally, producers often favor domestic subsidies and tariffs on imports in their home countries while objecting to subsidies and tariffs in their export markets.

Socialists frequently oppose free trade on the ground that it allows maximum exploitation of workers by capital. For example, Karl Marx wrote in The Communist Manifesto (1848): "The bourgeoisie [...] has set up that single, unconscionable freedom – free trade. In one word, for exploitation, veiled by religious and political illusions, it has substituted naked, shameless, direct, brutal exploitation". Marx supported free trade, however, solely because he felt that it would hasten the social revolution. He also viewed the tendency to support protectionism out of spite for free trade to be unsound. That is because Marx viewed protectionism as a means for domestic firms to establish "large-scale" industry within its borders, which would inevitably make it dependent on the world market so that it could make more revenue for example. He also argues that protectionism does not stop a country from developing a domestic economic system that ironically mirrors competitive free trade.

Many anti-globalization groups oppose free trade based on their assertion that free-trade agreements generally do not increase the economic freedom of the poor or of the working class and frequently make them poorer.

Some opponents of free trade favor free-trade theory but oppose free-trade agreements as applied. Some opponents of NAFTA see the agreement as materially harming the common people, but some of the arguments are actually against the particulars of government-managed trade, rather than against free trade per se. For example, it is argued that it would be wrong to let subsidized corn from the United States into Mexico freely under NAFTA at prices well below production cost (dumping) because of its ruinous effects to Mexican farmers.

Research shows that support for trade restrictions is highest among respondents with the lowest levels of education. Hainmueller and Hiscox find:

that the impact of education on how voters think about trade and globalization has more to do with exposure to economic ideas and information about the aggregate and varied effects of these economic phenomena, than it does with individual calculations about how trade affects personal income or job security. This is not to say that the latter types of calculations are not important in shaping individuals' views of trade – just that they are not being manifest in the simple association between education and support for trade openness

A 2017 study found that individuals whose occupations are routine-task-intensive and who do jobs that are offshorable are more likely to favor protectionism.

Research suggests that attitudes towards free trade do not necessarily reflect individuals' self-interests.

Colonialism

Various proponents of economic nationalism and of the school of mercantilism have long portrayed free trade as a form of colonialism or imperialism. In the 19th century, such groups criticized British calls for free trade as cover for British Empire, notably in the works of American Henry Clay, architect of the American System.

Free-trade debates and associated matters involving the colonial administration of Ireland have periodically (such as in 1846 and 1906) caused ructions in the British Conservative (Tory) Party (Corn Law issues in the 1820s to the 1840s, Irish Home Rule issues throughout the 19th and early-20th centuries).

Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa (in office from 2007 to 2017) denounced the "sophistry of free trade" in an introduction he wrote for a 2006 book, The Hidden Face of Free Trade Accords, which was written in part by Correa's Energy Minister Alberto Acosta. Citing as his source the 2002 book Kicking Away the Ladder written by Ha-Joon Chang, Correa identified the difference between an "American system" opposed to a "British System" of free trade. The Americans explicitly viewed the latter, he says, as "part of the British imperialist system". According to Correa, Chang showed that Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton (in office 1789–1795), rather than List, first presented a systematic argument defending industrial protectionism.

Major free trade areas

Africa

Europe

Americas

Alternatives

The following alternatives to free trade have been proposed: protectionism, imperialism, balanced trade, fair trade, and industrial policy. Protectionism involves tariffs to protect domestic goods and industry from international competition, and to raise government revenue in lieu of other forms of taxation. Imperialism entails unequal exchange for the benefit of the mother country, often at the expense of the colonies. Balanced and fair trade involves allowing trade but taking into account other interests, such as dirigisme, protecting labor rights, environmentalism, etc.

In literature

The value of free trade was first observed and documented in 1776 by Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations, writing:

It is the maxim of every prudent master of a family, never to attempt to make at home what it will cost him more to make than to buy. [...] If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it of them with some part of the produce of our own industry, employed in a way in which we have some advantage.

This statement uses the concept of absolute advantage to present an argument in opposition to mercantilism, the dominant view surrounding trade at the time which held that a country should aim to export more than it imports and thus amass wealth. Instead, Smith argues, countries could gain from each producing exclusively the goods in which they are most suited to, trading between each other as required for the purposes of consumption. In this vein, it is not the value of exports relative to that of imports that is important, but the value of the goods produced by a nation. However, the concept of absolute advantage does not address a situation where a country has no advantage in the production of a particular good or type of good.

This theoretical shortcoming was addressed by the theory of comparative advantage. Generally attributed to David Ricardo, who expanded on it in his 1817 book On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, it makes a case for free trade based not on absolute advantage in production of a good, but on the relative opportunity costs of production. A country should specialize in whatever good it can produce at the lowest cost, trading this good to buy other goods it requires for consumption. This allows for countries to benefit from trade even when they do not have an absolute advantage in any area of production. While their gains from trade might not be equal to those of a country more productive in all goods, they will still be better off economically from trade than they would be under a state of autarky.

Exceptionally, Henry George's 1886 book Protection or Free Trade was read out loud in full into the Congressional Record by five Democratic congressmen. American economist Tyler Cowen wrote that Protection or Free Trade "remains perhaps the best-argued tract on free trade to this day". Although George is very critical towards protectionism, he discusses the subject in particular with respect to the interests of labor:

We all hear with interest and pleasure of improvements in transportation by water or land; we are all disposed to regard the opening of canals, the building of railways, the deepening of harbors, the improvement of steamships as beneficial. But if such things are beneficial, how can tariffs be beneficial? The effect of such things is to lessen the cost of transporting commodities; the effect of tariffs is to increase it. If the protective theory be true, every improvement that cheapens the carriage of goods between country and country is an injury to mankind unless tariffs be commensurately increased.

George considers the general free trade argument inadequate. He argues that the removal of protective tariffs alone is never sufficient to improve the situation of the working class, unless accompanied by a shift towards a "single tax" in the form of a land value tax.