Armour (Commonwealth English) or armor (American English; see spelling differences) is a covering used to protect an object, individual, or vehicle from physical injury or damage, especially direct contact weapons or projectiles during combat, or from a potentially dangerous environment or activity (e.g. cycling, construction sites, etc.). Personal armour is used to protect soldiers and war animals. Vehicle armour is used on warships, armoured fighting vehicles, and some mostly ground attack combat aircraft.

A second use of the term armour describes armoured forces, armoured weapons, and their role in combat. After the development of armoured warfare, tanks and mechanised infantry and their combat formations came to be referred to collectively as "armour".

Etymology

The word "armour" began to appear in the Middle Ages as a derivative of Old French. It is dated from 1297 as a "mail, defensive covering worn in combat". The word originates from the Old French armure, itself derived from the Latin armatura meaning "arms and/or equipment", with the root armare meaning "arms or gear".

Personal

Armour has been used throughout recorded history. It has been made from a variety of materials, beginning with the use of leathers or fabrics as protection and evolving through chain mail and metal plate into today's modern composites. For much of military history the manufacture of metal personal armour has dominated the technology and employment of armour.

Armour drove the development of many important technologies of the Ancient World, including wood lamination, mining, metal refining, vehicle manufacture, leather processing, and later decorative metal working. Its production was influential in the industrial revolution, and furthered commercial development of metallurgy and engineering. Armour was the single most influential factor in the development of firearms, which in turn revolutionised warfare.

History

Significant factors in the development of armour include the economic and technological necessities of its production. For instance, plate armour first appeared in Medieval Europe when water-powered trip hammers made the formation of plates faster and cheaper. At times the development of armour has paralleled the development of increasingly effective weaponry on the battlefield, with armourers seeking to create better protection without sacrificing mobility.

Well-known armour types in European history include the lorica hamata, lorica squamata, and the lorica segmentata of the Roman legions, the mail hauberk of the early medieval age, and the full steel plate harness worn by later medieval and renaissance knights, and breast and back plates worn by heavy cavalry in several European countries until the first year of World War I (1914–1915). The samurai warriors of feudal Japan utilised many types of armour for hundreds of years up to the 19th century.

Early

Cuirasses and helmets were manufactured in Japan as early as the 4th century. Tankō, worn by foot soldiers and keikō, worn by horsemen were both pre-samurai types of early Japanese armour constructed from iron plates connected together by leather thongs. Japanese lamellar armour (keiko) passed through Korea and reached Japan around the 5th century. These early Japanese lamellar armours took the form of a sleeveless jacket, leggings and a helmet.

Armour did not always cover all of the body; sometimes no more than a helmet and leg plates were worn. The rest of the body was generally protected by means of a large shield. Examples of armies equipping their troops in this fashion were the Aztecs (13th to 15th century CE).

In East Asia, many types of armour were commonly used at different times by various cultures, including scale armour, lamellar armour, laminar armour, plated mail, mail, plate armour, and brigandine. Around the dynastic Tang, Song, and early Ming Period, cuirasses and plates (mingguangjia) were also used, with more elaborate versions for officers in war. The Chinese, during that time used partial plates for "important" body parts instead of covering their whole body since too much plate armour hinders their martial arts movement. The other body parts were covered in cloth, leather, lamellar, or Mountain pattern. In pre-Qin dynasty times, leather armour was made out of various animals, with more exotic ones such as the rhinoceros.

Mail, sometimes called "chainmail", made of interlocking iron rings is believed to have first appeared some time after 300 BC. Its invention is credited to the Celts; the Romans are thought to have adopted their design.

Gradually, small additional plates or discs of iron were added to the mail to protect vulnerable areas. Hardened leather and splinted construction were used for arm and leg pieces. The coat of plates was developed, an armour made of large plates sewn inside a textile or leather coat.

13th to 18th century Europe

Early plate in Italy, and elsewhere in the 13th–15th century, were made of iron. Iron armour could be carburised or case hardened to give a surface of harder steel. Plate armour became cheaper than mail by the 15th century as it required much less labour and labour had become much more expensive after the Black Death, though it did require larger furnaces to produce larger blooms. Mail continued to be used to protect those joints which could not be adequately protected by plate, such as the armpit, crook of the elbow and groin. Another advantage of plate was that a lance rest could be fitted to the breast plate.

The small skull cap evolved into a bigger true helmet, the bascinet, as it was lengthened downward to protect the back of the neck and the sides of the head. Additionally, several new forms of fully enclosed helmets were introduced in the late 14th century.

Probably the most recognised style of armour in the world became the plate armour associated with the knights of the European Late Middle Ages, but continuing to the early 17th century Age of Enlightenment in all European countries.

By 1400, the full harness of plate armour had been developed in armouries of Lombardy. Heavy cavalry dominated the battlefield for centuries in part because of their armour.

In the early 15th century, advances in weaponry allowed infantry to defeat armoured knights on the battlefield. The quality of the metal used in armour deteriorated as armies became bigger and armour was made thicker, necessitating breeding of larger cavalry horses. If during the 14–15th centuries armour seldom weighed more than 15 kg, then by the late 16th century it weighed 25 kg. The increasing weight and thickness of late 16th century armour therefore gave substantial resistance.

In the early years of low velocity firearms, full suits of armour, or breast plates actually stopped bullets fired from a modest distance. Crossbow bolts, if still in use, would seldom penetrate good plate, nor would any bullet unless fired from close range. In effect, rather than making plate armour obsolete, the use of firearms stimulated the development of plate armour into its later stages. For most of that period, it allowed horsemen to fight while being the targets of defending arquebusiers without being easily killed. Full suits of armour were actually worn by generals and princely commanders right up to the second decade of the 18th century. It was the only way they could be mounted and survey the overall battlefield with safety from distant musket fire.

The horse was afforded protection from lances and infantry weapons by steel plate barding. This gave the horse protection and enhanced the visual impression of a mounted knight. Late in the era, elaborate barding was used in parade armour.

Later

Gradually, starting in the mid-16th century, one plate element after another was discarded to save weight for foot soldiers.

Back and breast plates continued to be used throughout the entire period of the 18th century and through Napoleonic times, in many European heavy cavalry units, until the early 20th century. From their introduction, muskets could pierce plate armour, so cavalry had to be far more mindful of the fire. In Japan, armour continued to be used until the late 19th century, with the last major fighting in which armour was used, this occurred in 1868. Samurai armour had one last short lived use in 1877 during the Satsuma Rebellion.

Though the age of the knight was over, armour continued to be used in many capacities. Soldiers in the American Civil War bought iron and steel vests from peddlers (both sides had considered but rejected body armour for standard issue). The effectiveness of the vests varied widely, some successfully deflected bullets and saved lives, but others were poorly made and resulted in tragedy for the soldiers. In any case the vests were abandoned by many soldiers due to their increased weight on long marches, as well as the stigma they got for being cowards from their fellow troops.

At the start of World War I, thousands of the French Cuirassiers rode out to engage the German Cavalry. By that period, the shiny metallic cuirass was covered in a dark paint and a canvas wrap covered their elaborate Napoleonic style helmets, to help mitigate the sunlight being reflected off the surfaces, thereby alerting the enemy of their location. Their armour was only meant for protection against edged weapons such as bayonets, sabres, and lances. Cavalry had to be wary of repeating rifles, machine guns, and artillery, unlike the foot soldiers, who at least had a trench to give them some protection.

Present

Today, ballistic vests, also known as flak jackets, made of ballistic cloth (e.g. kevlar, dyneema, twaron, spectra etc.) and ceramic or metal plates are common among police forces, security staff, corrections officers and some branches of the military.

The US Army has adopted Interceptor body armour, which uses Enhanced Small Arms Protective Inserts (ESAPIs) in the chest, sides, and back of the armour. Each plate is rated to stop a range of ammunition including 3 hits from a 7.62×51 NATO AP round at a range of 10 m (33 ft). Dragon Skin is another ballistic vest which is currently in testing with mixed results. As of 2019, it has been deemed too heavy, expensive, and unreliable, in comparison to more traditional plates, and it is outdated in protection compared to modern US IOTV armour, and even in testing was deemed a downgrade from the IBA.

The British Armed Forces also have their own armour, known as Osprey. It is rated to the same general equivalent standard as the US counterpart, the Improved Outer Tactical Vest, and now the Soldier Plate Carrier System and Modular Tactical Vest.

The Russian Armed Forces also have armour, known as the 6B43, all the way to 6B45, depending on variant. Their armour runs on the GOST system, which, due to regional conditions, has resulted in a technically higher protective level overall.

-

Medieval German helmet.

-

Early Modern horse armour on display at Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, New York.

-

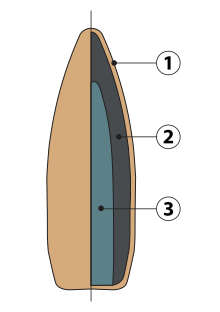

Plate armour

-

Riot police with body protection against physical impact. However, it does not provide very much protection against firearms.

Vehicle

The first modern production technology for armour plating was used by navies in the construction of the ironclad warship, reaching its pinnacle of development with the battleship. The first tanks were produced during World War I. Aerial armour has been used to protect pilots and aircraft systems since the First World War.

In modern ground forces' usage, the meaning of armour has expanded to include the role of troops in combat. After the evolution of armoured warfare, mechanised infantry were mounted in armoured fighting vehicles and replaced light infantry in many situations. In modern armoured warfare, armoured units equipped with tanks and infantry fighting vehicles serve the historic role of heavy cavalry, light cavalry, and dragoons, and belong to the armoured branch of warfare.

History

Ships

The first ironclad battleship, with iron armour over a wooden hull, Gloire, was launched by the French Navy in 1859 prompting the British Royal Navy to build a counter. The following year they launched HMS Warrior, which was twice the size and had iron armour over an iron hull. After the first battle between two ironclads took place in 1862 during the American Civil War, it became clear that the ironclad had replaced the unarmoured line-of-battle ship as the most powerful warship afloat.

Ironclads were designed for several roles, including as high seas battleships, coastal defence ships, and long-range cruisers. The rapid evolution of warship design in the late 19th century transformed the ironclad from a wooden-hulled vessel which carried sails to supplement its steam engines into the steel-built, turreted battleships and cruisers familiar in the 20th century. This change was pushed forward by the development of heavier naval guns (the ironclads of the 1880s carried some of the heaviest guns ever mounted at sea), more sophisticated steam engines, and advances in metallurgy which made steel shipbuilding possible.

The rapid pace of change in the ironclad period meant that many ships were obsolete as soon as they were complete, and that naval tactics were in a state of flux. Many ironclads were built to make use of the ram or the torpedo, which a number of naval designers considered the crucial weapons of naval combat. There is no clear end to the ironclad period, but towards the end of the 1890s the term ironclad dropped out of use. New ships were increasingly constructed to a standard pattern and designated battleships or armoured cruisers.

Trains

Armoured trains saw use from the mid-19th to the mid-20th century, including the American Civil War (1861–1865), the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871), the First and Second Boer Wars (1880–81 and 1899–1902), the Polish–Soviet War (1919–1921), the First (1914–1918) and Second World Wars (1939–1945) and the First Indochina War (1946–1954). The most intensive use of armoured trains was during the Russian Civil War (1918–1920).

Armoured fighting vehicles

Ancient siege engines were usually protected by wooden armour, often covered with wet hides or thin metal to prevent being easily burned.

Medieval war wagons were horse-drawn wagons that were similarly armoured. These contained guns or crossbowmen that could fire through gun-slits.

The first modern armoured fighting vehicles were armoured cars, developed circa 1900. These started as ordinary wheeled motor-cars protected by iron shields, typically mounting a machine gun.

During the First World War, the stalemate of trench warfare during on the Western Front spurred the development of the tank. It was envisioned as an armoured machine that could advance under fire from enemy rifles and machine guns, and respond with its own heavy guns. It used caterpillar tracks to cross ground broken up by shellfire and trenches.

Aircraft

With the development of effective anti-aircraft artillery in the period before the Second World War, military pilots, once the "knights of the air" during the First World War, became far more vulnerable to ground fire. As a response, armour plating was added to aircraft to protect aircrew and vulnerable areas such as engines and fuel tanks. Self-sealing fuel tanks functioned like armour in that they added protection but also increased weight and cost.

Present

Tank armour has progressed from the Second World War armour forms, now incorporating not only harder composites, but also reactive armour designed to defeat shaped charges. As a result of this, the main battle tank (MBT) conceived in the Cold War era can survive multiple rocket-propelled grenade strikes with minimal effect on the crew or the operation of the vehicle. The light tanks that were the last descendants of the light cavalry during the Second World War have almost completely disappeared from the world's militaries due to increased lethality of the weapons available to the vehicle-mounted infantry.

The armoured personnel carrier (APC) was devised during the First World War. It allows the safe and rapid movement of infantry in a combat zone, minimising casualties and maximising mobility. APCs are fundamentally different from the previously used armoured half-tracks in that they offer a higher level of protection from artillery burst fragments, and greater mobility in more terrain types. The basic APC design was substantially expanded to an infantry fighting vehicle (IFV) when properties of an APC and a light tank were combined in one vehicle.

Naval armour has fundamentally changed from the Second World War doctrine of thicker plating to defend against shells, bombs and torpedoes. Passive defence naval armour is limited to kevlar or steel (either single layer or as spaced armour) protecting particularly vital areas from the effects of nearby impacts. Since ships cannot carry enough armour to completely protect against anti-ship missiles, they depend more on defensive weapons destroying incoming missiles, or causing them to miss by confusing their guidance systems with electronic warfare.

Although the role of the ground attack aircraft significantly diminished after the Korean War, it re-emerged during the Vietnam War, and in the recognition of this, the US Air Force authorised the design and production of what became the A-10 dedicated anti-armour and ground-attack aircraft that first saw action in the Gulf War.

High-voltage transformer fire barriers are often required to defeat ballistics from small arms as well as projectiles from transformer bushings and lightning arresters, which form part of large electrical transformers, per NFPA 850. Such fire barriers may be designed to inherently function as armour, or may be passive fire protection materials augmented by armour, where care must be taken to ensure that the armour's reaction to fire does not cause issues with regards to the fire barrier being armoured to defeat explosions and projectiles in addition to fire, especially since both functions must be provided simultaneously, meaning they must be fire-tested together to provide realistic evidence of fitness for purpose.

Combat drones use little to no vehicular armour as they are not manned vessels, this results in them being lightweight and small in size.

Animal armour

Horse armour

Body armour for war horses has been used since at least 2000 BC. Cloth, leather, and metal protection covered cavalry horses in ancient civilisations, including ancient Egypt, Assyria, Persia, and Rome. Some formed heavy cavalry units of armoured horses and riders used to attack infantry and mounted archers. Armour for horses is called barding (also spelled bard or barb) especially when used by European knights.

During the late Middle Ages as armour protection for knights became more effective, their mounts became targets. This vulnerability was exploited by the Scots at the Battle of Bannockburn in the 14th century, when horses were killed by the infantry, and for the English at the Battle of Crécy in the same century where longbowmen shot horses and the then dismounted French knights were killed by heavy infantry. Barding developed as a response to such events.

Examples of armour for horses could be found as far back as classical antiquity. Cataphracts, with scale armour for both rider and horse, are believed by many historians to have influenced the later European knights, via contact with the Byzantine Empire.

Surviving period examples of barding are rare; however, complete sets are on display at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Wallace Collection in London, the Royal Armouries in Leeds, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Horse armour could be made in whole or in part of cuir bouilli (hardened leather), but surviving examples of this are especially rare.

Elephant armour

War elephants were first used in ancient times without armour, but armour was introduced because elephants injured by enemy weapons would often flee the battlefield. Elephant armour was often made from hardened leather, which was fitted onto an individual elephant while moist, then dried to create a hardened shell. Alternatively, metal armour pieces were sometimes sewn into heavy cloth. Later lamellar armour (small overlapping metal plates) was introduced. Full plate armour was not typically used due to its expense and the danger of the animal overheating.