In spaceflight, an orbital maneuver (otherwise known as a burn) is the use of propulsion systems to change the orbit of a spacecraft. For spacecraft far from Earth (for example those in orbits around the Sun) an orbital maneuver is called a deep-space maneuver (DSM).

The rest of the flight, especially in a transfer orbit, is called coasting.

General

Rocket equation

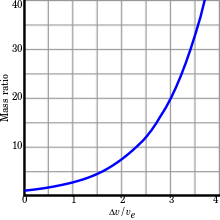

The Tsiolkovsky rocket equation, or ideal rocket equation is an equation that is useful for considering vehicles that follow the basic principle of a rocket: where a device that can apply acceleration to itself (a thrust) by expelling part of its mass with high speed and moving due to the conservation of momentum. Specifically, it is a mathematical equation that relates the delta-v (the maximum change of speed of the rocket if no other external forces act) with the effective exhaust velocity and the initial and final mass of a rocket (or other reaction engine.)

For any such maneuver (or journey involving a number of such maneuvers):

where:

- is the initial total mass, including propellant,

- is the final total mass,

- is the effective exhaust velocity ( where is the specific impulse expressed as a time period and is standard gravity),

- is delta-v - the maximum change of velocity of the vehicle (with no external forces acting).

Delta-v

The applied change in velocity of each maneuver is referred to as delta-v ().

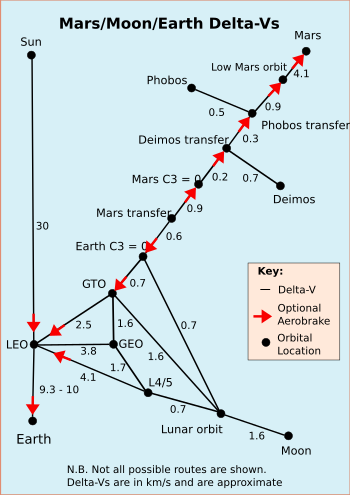

The delta-v for all the expected maneuvers are estimated for a mission. They are summarized in a delta-v budget. With a good approximation of the delta-v budget designers can estimate the fuel to payload requirements of the spacecraft using the rocket equation.

Impulsive maneuvers

An "impulsive maneuver" is the mathematical model of a maneuver as an instantaneous change in the spacecraft's velocity (magnitude and/or direction) as illustrated in figure 1. It is the limit case of a burn to generate a particular amount of delta-v, as the burn time tends to zero.

In the physical world no truly instantaneous change in velocity is possible as this would require an "infinite force" applied during an "infinitely short time" but as a mathematical model it in most cases describes the effect of a maneuver on the orbit very well.

The off-set of the velocity vector after the end of real burn from the velocity vector at the same time resulting from the theoretical impulsive maneuver is only caused by the difference in gravitational force along the two paths (red and black in figure 1) which in general is small.

In the planning phase of space missions designers will first approximate their intended orbital changes using impulsive maneuvers that greatly reduces the complexity of finding the correct orbital transitions.

Low thrust for a long time

Applying a low thrust over a longer period of time is referred to as a non-impulsive maneuver. 'Non-impulsive' refers to the momentum changing slowly over a long time, as in electrically powered spacecraft propulsion, rather than by a short impulse.

Another term is finite burn, where the word "finite" is used to mean "non-zero", or practically, again: over a longer period.

For a few space missions, such as those including a space rendezvous, high fidelity models of the trajectories are required to meet the mission goals. Calculating a "finite" burn requires a detailed model of the spacecraft and its thrusters. The most important of details include: mass, center of mass, moment of inertia, thruster positions, thrust vectors, thrust curves, specific impulse, thrust centroid offsets, and fuel consumption.

Assists

Oberth effect

In astronautics, the Oberth effect is where the use of a rocket engine when travelling at high speed generates much more useful energy than one at low speed. Oberth effect occurs because the propellant has more usable energy (due to its kinetic energy on top of its chemical potential energy) and it turns out that the vehicle is able to employ this kinetic energy to generate more mechanical power. It is named after Hermann Oberth, the Austro-Hungarian-born, German physicist and a founder of modern rocketry, who apparently first described the effect.

The Oberth effect is used in a powered flyby or Oberth maneuver where the application of an impulse, typically from the use of a rocket engine, close to a gravitational body (where the gravity potential is low, and the speed is high) can give much more change in kinetic energy and final speed (i.e. higher specific energy) than the same impulse applied further from the body for the same initial orbit.

Since the Oberth maneuver happens in a very limited time (while still at low altitude), to generate a high impulse the engine necessarily needs to achieve high thrust (impulse is by definition the time multiplied by thrust). Thus the Oberth effect is far less useful for low-thrust engines, such as ion thrusters.

Historically, a lack of understanding of this effect led investigators to conclude that interplanetary travel would require completely impractical amounts of propellant, as without it, enormous amounts of energy are needed.

Gravitational assist

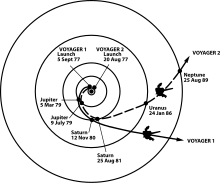

In orbital mechanics and aerospace engineering, a gravitational slingshot, gravity assist maneuver, or swing-by is the use of the relative movement and gravity of a planet or other celestial body to alter the path and speed of a spacecraft, typically in order to save propellant, time, and expense. Gravity assistance can be used to accelerate, decelerate and/or re-direct the path of a spacecraft.

The "assist" is provided by the motion (orbital angular momentum) of the gravitating body as it pulls on the spacecraft. The technique was first proposed as a mid-course manoeuvre in 1961, and used by interplanetary probes from Mariner 10 onwards, including the two Voyager probes' notable fly-bys of Jupiter and Saturn.

Transfer orbits

Orbit insertion is a general term for a maneuver that is more than a small correction. It may be used for a maneuver to change a transfer orbit or an ascent orbit into a stable one, but also to change a stable orbit into a descent: descent orbit insertion. Also the term orbit injection is used, especially for changing a stable orbit into a transfer orbit, e.g. trans-lunar injection (TLI), trans-Mars injection (TMI) and trans-Earth injection (TEI).

Hohmann transfer

In orbital mechanics, the Hohmann transfer orbit is an elliptical orbit used to transfer between two circular orbits of different altitudes, in the same plane.

The orbital maneuver to perform the Hohmann transfer uses two engine impulses which move a spacecraft onto and off the transfer orbit. This maneuver was named after Walter Hohmann, the German scientist who published a description of it in his 1925 book Die Erreichbarkeit der Himmelskörper (The Accessibility of Celestial Bodies). Hohmann was influenced in part by the German science fiction author Kurd Laßwitz and his 1897 book Two Planets.

Bi-elliptic transfer

In astronautics and aerospace engineering, the bi-elliptic transfer is an orbital maneuver that moves a spacecraft from one orbit to another and may, in certain situations, require less delta-v than a Hohmann transfer maneuver.

The bi-elliptic transfer consists of two half elliptic orbits. From the initial orbit, a delta-v is applied boosting the spacecraft into the first transfer orbit with an apoapsis at some point away from the central body. At this point, a second delta-v is applied sending the spacecraft into the second elliptical orbit with periapsis at the radius of the final desired orbit, where a third delta-v is performed, injecting the spacecraft into the desired orbit.

While they require one more engine burn than a Hohmann transfer and generally requires a greater travel time, some bi-elliptic transfers require a lower amount of total delta-v than a Hohmann transfer when the ratio of final to initial semi-major axis is 11.94 or greater, depending on the intermediate semi-major axis chosen.

The idea of the bi-elliptical transfer trajectory was first published by Ary Sternfeld in 1934.

Low energy transfer

A low energy transfer, or low energy trajectory, is a route in space which allows spacecraft to change orbits using very little fuel. These routes work in the Earth-Moon system and also in other systems, such as traveling between the satellites of Jupiter. The drawback of such trajectories is that they take much longer to complete than higher energy (more fuel) transfers such as Hohmann transfer orbits.

Low energy transfer are also known as weak stability boundary trajectories, or ballistic capture trajectories.

Low energy transfers follow special pathways in space, sometimes referred to as the Interplanetary Transport Network. Following these pathways allows for long distances to be traversed for little expenditure of delta-v.

Orbital inclination change

Orbital inclination change is an orbital maneuver aimed at changing the inclination of an orbiting body's orbit. This maneuver is also known as an orbital plane change as the plane of the orbit is tipped. This maneuver requires a change in the orbital velocity vector (delta v) at the orbital nodes (i.e. the point where the initial and desired orbits intersect, the line of orbital nodes is defined by the intersection of the two orbital planes).

In general, inclination changes can require a great deal of delta-v to perform, and most mission planners try to avoid them whenever possible to conserve fuel. This is typically achieved by launching a spacecraft directly into the desired inclination, or as close to it as possible so as to minimize any inclination change required over the duration of the spacecraft life.

Maximum efficiency of inclination change is achieved at apoapsis, (or apogee), where orbital velocity is the lowest. In some cases, it may require less total delta v to raise the spacecraft into a higher orbit, change the orbit plane at the higher apogee, and then lower the spacecraft to its original altitude.

Constant-thrust trajectory

Constant-thrust and constant-acceleration trajectories involve the spacecraft firing its engine in a prolonged constant burn. In the limiting case where the vehicle acceleration is high compared to the local gravitational acceleration, the spacecraft points straight toward the target (accounting for target motion), and remains accelerating constantly under high thrust until it reaches its target. In this high-thrust case, the trajectory approaches a straight line. If it is required that the spacecraft rendezvous with the target, rather than performing a flyby, then the spacecraft must flip its orientation halfway through the journey, and decelerate the rest of the way.

In the constant-thrust trajectory, the vehicle's acceleration increases during thrusting period, since the fuel use means the vehicle mass decreases. If, instead of constant thrust, the vehicle has constant acceleration, the engine thrust must decrease during the trajectory.

This trajectory requires that the spacecraft maintain a high acceleration for long durations. For interplanetary transfers, days, weeks or months of constant thrusting may be required. As a result, there are no currently available spacecraft propulsion systems capable of using this trajectory. It has been suggested that some forms of nuclear (fission or fusion based) or antimatter powered rockets would be capable of this trajectory.

More practically, this type of maneuver is used in low thrust maneuvers, for example with ion engines, Hall-effect thrusters, and others. These types of engines have very high specific impulse (fuel efficiency) but currently are only available with fairly low absolute thrust.

Rendezvous and docking

Orbit phasing

In astrodynamics orbit phasing is the adjustment of the time-position of spacecraft along its orbit, usually described as adjusting the orbiting spacecraft's true anomaly.

Space rendezvous and docking

A space rendezvous is an orbital maneuver during which two spacecraft, one of which is often a space station, arrive at the same orbit and approach to a very close distance (e.g. within visual contact). Rendezvous requires a precise match of the orbital velocities of the two spacecraft, allowing them to remain at a constant distance through orbital station-keeping. Rendezvous may or may not be followed by docking or berthing, procedures which bring the spacecraft into physical contact and create a link between them.