| Planet of the Humans | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Jeff Gibbs |

| Produced by | Jeff Gibbs Ozzie Zehner |

| Starring | Jeff Gibbs Nina Jablonski Ozzie Zehner Richard Heinberg |

| Distributed by | Rumble Media and YouTube |

Release date |

|

Running time | 100 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Planet of the Humans is a 2019 American environmental documentary film written, directed, and produced by Jeff Gibbs. The film was executively produced by Michael Moore. Moore released it on YouTube for free viewing on April 21, 2020, the eve of the 50th anniversary of the first Earth Day.

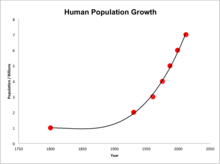

The film examines mainstream environmental groups' partnerships with billionaires, corporations, and wealthy family foundations in the fight to save the planet. The film questions whether green energy can solve society's expanding resource depletion without reducing consumption and/or population growth, as all existing forms of energy generation require some kind of consumption of finite resources. Essentially the film questions whether renewable energy sources such as biomass energy, wind power, and solar energy are as clean and renewable as they are portrayed to be.

Upon its release, Planet of the Humans generated intense controversy and critical reception was mixed. It was criticized by some climate scientists, environmentalists and renewable energy proponents as misleading and outdated, but received praise for its contrarian stance and for provoking discussion. The filmmakers have defended the film from criticism. On May 25, 2020, Planet of the Humans was removed from YouTube in response to a claim of copyright infringement, which PEN America condemned as censorship. The filmmakers challenged the claim, arguing that the fragment was used under fair use and that free speech was subverted. Twelve days later, YouTube allowed the film to be viewed again. In November 2020, Moore removed it from YouTube where it was available for free and made it available on Amazon, Apple and Google's rental channels, although a copy remains on the Internet Archive. As of 2023, the documentary is available on Michael Moore's official YouTube channel.

Synopsis

Planet of the Humans takes a critical look at the mainstream environmental movement, questioning its leaders' decision to partner with billionaires, corporations, and wealthy family foundations, and to promote renewable energy technology as the solution to climate change. Writer and narrator Jeff Gibbs admits to being a long-time fan of renewable energy and examines some of its implications.

After Barack Obama had directed billions of dollars into renewable energy, Gibbs follows the green energy movement more closely but is disappointed, finding that it wasn't what it seemed. Attending General Motors' Chevy Volt press conference in 2010, he learns that charging is done by a fossil fuel grid. He finds that his local solar array could only power 10 homes over a year. On a hike to a wind turbine construction site in Vermont he finds part of the mountainside being removed. This leads Gibbs to ask if machines made by our industrial civilization can save us from industrialization.

Gibbs interviews environmental sociologist Richard York, whose study in Nature, found that renewables were not displacing fossil fuels. Gibbs also speaks with author Richard Heinberg and anthropologist Nina Jablonski on why people seek technological fixes. Gibbs then interviews Ozzie Zehner, author of Green Illusions (2012), who states that solar, wind, and electric vehicle technologies require mined minerals, including rare earths, and heavy industrial processes to produce, with new mines opening as demand for green technology rises.

Gibbs speaks to a series of solar industry insiders, an electrical engineer, and a Federal Energy Regulatory Commissioner about solar energy’s intermittency limitation and reliance on baseload plants. Zehner describes how while the Sierra Club’s "Beyond Coal" campaign has closed coal plants, natural gas plants were opening in their wake, resulting in the overall expansion of fossil fuel use in the US. Green tech investor Robert F. Kennedy Jr. speaks to an oil and gas industry group, stating: "The plants that we're building, the wind plants and the solar plants, are gas plants."

Zehner discusses how companies including Apple and Tesla claim to run on 100% renewable energy despite remaining hooked up to the grid, and describes the Koch Brothers' involvement in green technology production. A three-minute montage shows the scale of industrial mining required renewable technologies, and Gibbs describes how solar and wind arrays must be replaced after only a few decades.

Gibbs then visits Steven Running, an ecologist from the University of Montana, who discusses planetary limits to global fish production, agricultural land, water irrigation, and ground water. Gibbs ends the section by speaking to social-psychologist Sheldon Solomon positing whether faith in renewables could be a reflection of a fear of death.

The next section investigates biomass. Gibbs sneaks onto a biomass plant property in Vermont and finds that instead of burning forest residue as advertised, the plant is surrounded by whole trees. A citizen activist in Michigan describes how her local biomass plant burns pentachlorophenol and creosote-treated railroad ties shipped in from Canada as well as rubber tires, which cause black snow to appear at the adjacent elementary school. Gibbs explores the practice of universities committing to "go green" by opening biomass plants on campus, tracing the practice back to a college in Middlebury, VT, endorsed by Bill McKibben. Gibbs states that biomass energy remains the largest percentage of renewable energy in the world. He then explores what he calls the "language loopholes" that allow for the continuation of biomass around the U.S. The section ends with Gibbs, as part of a media event at the Climate March in New York City, asking environmental leaders for their stance on biomass including Van Jones, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., Bill McKibben, and Vandana Shiva. Only Shiva denounces biomass & biofuels.

In the last third of the film, Gibbs explores the partnerships between mainstream environmental groups and Wall Street investors, billionaires, and wealthy family foundations. Gibbs displays a tax return showing that the Sierra Club accepted $3 million from timber investor Jeremy Grantham. Bill McKibben of 350.org is shown on stage with former Goldman Sachs executive David Blood, supporting his call to raise $40–50 trillion in green energy investments. Gibbs displays U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission filings of green funds promoted in divestment campaigns by McKibben and the Sierra Club, which show holdings in mining companies, oil and gas infrastructure, various banks including BlackRock, as well as Halliburton, McDonalds, Coca-Cola, Exxon, Chevron, Gazprom, and Enviva among others. Gibbs shows corporate formation documents indicating that Al Gore partnered with David Blood to start Generation Investment Management, a sustainability investment fund, before releasing An Inconvenient Truth. Gibbs then shows Gore lobbying Congress on behalf of the sugarcane ethanol industry in Brazil, juxtaposing footage of indigenous cultures in Brazil being evicted from their land to create more sugarcane fields.

Gibbs asserts that the environmental movement has been completely taken over by capitalism. The film shows McKibben stating that 350.org receives funding from The Rockefeller Brothers Fund, and the V. Kann Rasmussen Foundation. He also shows Gore in multiple interviews defending his decision to sell his American television channel, Current TV, earning him an estimated $100 million pre-tax for the deal, to Al Jazeera, which is owned by the State of Qatar, an oil and gas producer. Gibbs attends an Earth Day concert celebration in Washington, DC sponsored by Toyota, Citibank, and Caterpillar, where Dennis Hayes claims the entire event is run on solar energy. Backstage, Gibbs discovers the concert is actually being run by biodiesel generators.

The film ends with Gibbs reflecting that "Infinite growth on a finite planet is suicide", imploring the audience to take back the environmental movement from billionaires and capitalists. The final scene shows a mother and baby orangutan struggling to survive as the forest is logged and burned around them.

Production and content

Planet of the Humans was written, directed, and narrated by Jeff Gibbs. Michael Moore served as executive producer. The producers of Planet of the Humans are Gibbs and Ozzie Zehner; co-producers are Valorie Gibbs, Christopher Henze and David Paxson; cinematography by Gibbs, Zehner, and Christopher Henze; editing by Gibbs and Angela Vargos; sound mixing by Christopher Henze. Gibbs also composed some of the film's score.

Its content consists of energy-related footage, street interviews, formal interviews, and archival footage of businessmen and prominent environmental leaders. Footage includes satellite views of America's night skies, construction of a wind turbine, a solar fair, a wind farm construction site, a solar array owned by Lansing Power and Light Company, the Ivanpah Solar Power Facility, biomass facilities, and public events where prominent environmental leaders were speaking. Interviews were done by a camera crew that identified themselves as being from New World Media during public events. These interviews were preceded by a number of formal interviews with Richard Heinberg, Ozzie Zehner, and Penn State anthropologist Nina Jablonski. The voice-over for much of the film was undertaken by Jeff Gibbs.

Release

The film received its world premiere at the Traverse City Film Festival (TCFF) in July 2019. On April 21, 2020, the eve of Earth Day, Moore announced that the film would be available for free on YouTube for 30 days, which was later extended by another month because of high viewership.

In an interview held at TCFF, Gibbs stated that "the film is not expected to be a comfortable beginning to the needed conversation", especially for those who treat solar and wind energy like "sacred cows".

The Films For Action website originally promoted the documentary. After protests stating that "the film is full of misinformation", they removed the embedded link and published a statement listing multiple falsehoods and errors, including statements about environmental organizations and solar and wind power that were outdated or incorrect. On May 7, Films for Action restored the embedded link, stating their concern that "taking the film down in the context of Josh's retraction campaign was only going to create headlines, generate more interest in the film, and possibly lead people to think we're trying to 'cover up the truth,' giving the film more power and mystique than it deserves".

On May 25, 2020, the film was temporarily removed from YouTube due to a copyright infringement claim by British environmental photographer Toby Smith over a 4-second segment Gibbs considered fair-use content. The controversial video had more than 8 million YouTube views at the time. Moore and Gibbs called the move a "blatant act of censorship" and disputed the claim with YouTube. The producers made the video available for free streaming on the competing Vimeo platform.

On November 18, 2020, Moore took it down from his "rumble" YouTube channel where it was available for free and instead made it available on Amazon, Apple and Google's rental channels. As of 2023, the documentary is available on Michael Moore's official youtube channel.

Factual accuracy

Scientific accuracy

The movie was criticized as outdated and misleading by some climate scientists. The film claims the carbon footprint of renewable energy is comparable to fossil fuels, when taking into account all different stages of its production. However, a large body of research shows the life-cycle emissions of wind and solar are much lower than those of fossil fuels.

The film uses footage of a solar field that is up to a decade old, which critics argue may give a false impression of the maturity of the technologies in the present day. One field of solar panels the documentary shows operates with 8% efficiency of sunlight conversion, which is below the typical 15-20% efficiency of solar panels in use in 2020.

The film also includes footage of a 10-year-old electric vehicle being recharged from a grid that is 95% powered by coal. The emissions intensity of electric vehicles varies depending on the source of electricity used to power the grid; however, as of 2020, they emit less than internal combustion vehicles in all but a few of the world's regions. As of 2015, electric vehicles emit on average 31% less than internal combustion vehicles for the same distance travelled. The average power grid derived slightly more than 60% of its energy from fossil fuels in 2019.

A pie chart is shown in the film with total battery storage compared to yearly energy use, which is a factor of thousand higher. The filmmakers suggest that this amount of energy storage is needed to make sure intermittency of renewables does not lead to power outages. In reality, battery storage is only part of solving intermittency, and using a mix of different energy sources reduces the need for batteries.

In a letter, filmmaker and environmental activist Josh Fox and academics including climate scientist Michael Mann have asked for an apology and a retraction of the film. They say the film includes "various distortions, half-truths and lies", and that the filmmakers "have done a grave disservice to us and the planet by promoting climate change inactivist tropes and talking points".

The film includes egregious misquotes. For example, the film heavily criticizes logging-based biomass projects and then incorrectly implies that many environmental groups are strong supporters of such projects. At 1:05:54, the film shows a quote from the Sierra Club Biomass Guidelines saying "biomass projects can be sustainable." This quote is taken entirely out of context and is a misrepresentation of the document which states that:

"We believe that biomass projects can be sustainable, but that many biomass projects are not. We are not confident that massive new biomass energy resources are available without risking soil and forest health, given the lack of commitment by governments and industry to preservation, restoration, and conservation of natural resources".

Claims about the environmental movement

The Union of Concerned Scientists, which was mentioned in the movie, responded to the allegations: "it implies that UCS took money from corporations profiting from EVs, without (again) stopping to check the facts, or reaching out to UCS about it. It wouldn't have been hard, either way, to discover that UCS doesn't take corporate money at all".

Environmentalist Bill McKibben responded to claims made in the documentary about him and the organization he cofounded, 350.org:

"A Youtube video emerged on Earth Day eve making charges about me and about 350.org — namely that I was a supporter of biomass energy, and that 350 and I were beholden to corporate funding, and have misled our supporters on the costs and trade-offs related to decarbonizing our economy. These things aren't true".

In Rolling Stone, McKibben continued: "the filmmakers didn't just engage in bad journalism (though they surely did), they acted in bad faith. They didn't just behave dishonestly (though they surely did), they behaved dishonorably. I'm aware that in our current salty era those words may sound mild, but in my lexicon they are the strongest possible epithets."

Reception

It has been viewed 12.5 million times on YouTube.

On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 65%, based on 26 reviews, with an average rating of 6.3/10. On Metacritic it has a score of 56% based on reviews from five critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".

Supporters of the film praised it for provoking discussion. Writing for The Guardian, Peter Bradshaw called the film "refreshingly contrarian" saying that "it's always valuable to re-examine a sacred cow" and praising the film for focusing on "liberal A-listers" and refraining from attacking Greta Thunberg, but criticised the film for being vague about solutions and not examining nuclear power.

Gary Mason at The Globe and Mail referred to the film as "The Michael Moore-backed film enviros are dreading".

Nonfictionfilm.com editor-in-chief, Matthew Carey, wrote: "Films about environmental issues have long been a staple of the documentary form, a genre that in recent years alone has brought us Before the Flood, Chasing Ice, Chasing Coral and, of course, An Inconvenient Truth. But those documentaries arguably pale in importance to Planet of the Humans".

Julie Ann Grimm of the Santa Fe Reporter praised the film saying that "Gibbs highlights how the global environmental cost of mining, production and disposal of solar and wind technology don’t get primetime play" and calling it a "enjoyable if also gut-rotting indictment of Big Environment and some of its figureheads" concluding that "It's ... a must-watch".

Adrian Hennigan, features editor at Haaretz, called Planet of the Humans a "provocative documentary about how capitalism has destroyed the environmental movement" and stated: "This cri de coeur from American producer-composer-editor Gibbs may lack balance and counterarguments, but it convincingly makes the case that 'less must be the new more' if humankind is to have any chance of not being wiped out due to overpopulation and overconsumption".

The Las Vegas Review-Journal editorial page wrote of the movie, "As Mr. Moore and Mr. Gibbs have uncovered, renewable energy proponents have been much better at making promises than keeping them", noting that "they aren’t the only ones who’ve noticed that renewable energy is heavily dependent on things that aren’t so renewable", pointing to an article in the Wall Street Journal by Mark P. Mills. However, they were less positive about the film's scepticism of companies, saying: "But the duo seem particularly aghast ... that any transition to green energy will require massive investment from evil industrialists and capitalists who might turn a profit. Who knew?".

For Resilience, Heinberg has also written: "[The film] starts a conversation we need to have, and it's a film that deserves to be seen" and "Mainstream enviros will hate this movie because it exposes some of their real failings. By focusing on techno-fixes, they have side-lined nearly all discussion of overpopulation and overconsumption".

Louis Proyect of CounterPunch praised the film for going against the "liberal establishment".

Dennis Harvey in Variety claimed "Gibbs' dull monotone makes him a poor narrator", "there's nothing particularly elegant about the way Planet of the Humans arrives at its downbeat thesis," and "though well-shot and edited, the material here is simply too sprawling to avoid feeling crammed into one ungainly package".

Criticism of accuracy

University of California environmental policy professor Leah Stokes of Vox claimed that the movie undermines the work of young climate activists and that "throughout, the filmmakers twist basic facts, misleading the public about who is responsible for the climate crisis. We are used to climate science misinformation campaigns from fossil fuel corporations. But from progressive filmmakers?" Dana Nucitelli of Yale Climate Connections claims: "The film's case is akin to arguing that because fruit contains sugar, eating strawberries is no healthier than eating a cheesecake". The Post Carbon Institute, a sustainability think tank closely connected with interviewee Richard Heinberg, published a podcast that criticizes the film.

Emily Atkin, environmental journalist for The New Republic, described the documentary as "an argumentative essay from a lazy college freshman". Josh Fox of The Nation claimed that the film is "wildly unscientific, outdated, full of falsehoods, and benefits fossil fuel industry promoters and climate deniers." InsideClimate News argued that the movie "will almost certainly do far more harm than good in the struggle to reduce carbon emissions".

Criticism of comments on overpopulation

Environmental journalist Brian Kahn of Earther argued that the filmmaker's choice to have "mostly white experts who are mostly men" argue in favor of population control gives the film "a bit more than a whiff of eugenics and ecofascism. [...] What's most frustrating about Gibbs' film is he walks right up to some serious issues and ignores clear solutions", Kahn concluded. Jacobin wrote that the film "embraces bad science on renewable energy and anti-humanist, anti–working class narratives of overpopulation and overconsumption", concluding that by "focusing on industrial civilization and 'overpopulation' as the cause of environmental problems, Moore and Gibbs distract us from the real problem: the untrammeled market." Ted Nordhaus, an environmental policy writer and proponent of nuclear energy and industrial agriculture, argued that "the treatment of renewables [in the film] is a mirror image of the misinformation that the anti-nuclear movement has trafficked in for decades." and called the overall message of the film "apocalyptic neo-Malthusian nihilism".

In The Guardian, George Monbiot wrote: "The film does not deny climate science. But it promotes the discredited myths that [climate change] deniers have used for years to justify their position. It claims that environmentalism is a self-seeking scam, doing immense harm to the living world while enriching a group of con artists". According to Monbiot, its "attacks on solar and wind power rely on a series of blatant falsehoods". Monbiot further criticised the film's focus on discussions of overpopulation, saying: "When wealthy people, such as Moore and Gibbs, point to this issue without the necessary caveats, they are saying, in effect, 'it's not Us consuming, it’s Them breeding.'"

In a review of the film for Deep Green Resistance News Service, radical feminist Elisabeth Robson said the population issue was a "relatively minor point in the film compared to the points about solar, wind, and biomass" and "the film did a fairly good job of raising it as an issue without being particularly 'Malthusian' about it." She also opined that "it is very clear that 8 billion humans would not exist without massive amounts of fossil fuels. I don’t think many would argue with that at this point (and if you have a cogent argument, I'd like to see it)".

Producers' response

Michael Moore, Jeff Gibbs, and Ozzie Zehner responded to the critics on an episode of Rising. In the interview Gibbs states that

"we don't attack environmental leaders. We need our environmental leaders." Gibbs also states that "We went to great pains to show you what's happening in the field of solar and wind. And many of our experts are in the solar and wind industry". In summarizing his primary intent for making the movie, Gibbs states that "I wanted to spark a holistic discussion about all the things we humans are doing and whether these green technologies were even going to solve climate change let alone all the other things happening around the planet."

When pressed in the Rising interview about accusations that the film presents a Malthusian point of view, Gibbs responded that they never used the term "population control" and are not in favor of it, and added that a recent UN study on the extinction crisis also mentioned population growth and economic growth as the primary drivers of the crisis.

Jeff Gibbs has said that the film is designed to prompt discussion and debate beyond the narrow issue of climate change and to look at the overall human impact on the environment, including issues such as human overpopulation and the contemporary extinction crisis in which half of all wildlife has disappeared in the last 40 years, and whether green technology can solve these issues.