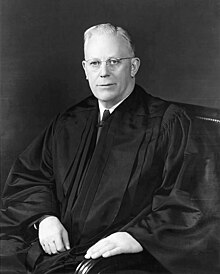

Earl Warren | |

|---|---|

| |

| 14th Chief Justice of the United States | |

| In office October 5, 1953 – June 23, 1969 | |

| Nominated by | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | Fred M. Vinson |

| Succeeded by | Warren E. Burger |

| 30th Governor of California | |

| In office January 4, 1943 – October 5, 1953 | |

| Lieutenant | Frederick F. Houser Goodwin Knight |

| Preceded by | Culbert Olson |

| Succeeded by | Goodwin Knight |

| 20th Attorney General of California | |

| In office January 3, 1939 – January 4, 1943 | |

| Governor | Culbert Olson |

| Preceded by | Ulysses S. Webb |

| Succeeded by | Robert W. Kenny |

| Chair of the California Republican Party | |

| In office 1932–1938 | |

| Preceded by | Louis B. Mayer |

| Succeeded by | Justus Craemer |

| District Attorney of Alameda County | |

| In office 1925–1939 | |

| Preceded by | Ezra Decoto |

| Succeeded by | Ralph Hoyt |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 19, 1891 Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Died | July 9, 1974 (aged 83) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Nina Meyers (m. 1925) |

| Children | 6 |

| Education | University of California, Berkeley (BA, LLB) |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1917–1918 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | 91st Division |

Earl Warren (March 19, 1891 – July 9, 1974) was an American attorney, politician, and jurist who served as the 30th governor of California from 1943 to 1953 and as the 14th Chief Justice of the United States from 1953 to 1969. The Warren Court presided over a major shift in American constitutional jurisprudence, which has been recognized by many as a "Constitutional Revolution" in the liberal direction, with Warren writing the majority opinions in landmark cases such as Brown v. Board of Education (1954), Reynolds v. Sims (1964), Miranda v. Arizona (1966), and Loving v. Virginia (1967). Warren also led the Warren Commission, a presidential commission that investigated the 1963 assassination of President John F. Kennedy. He served as Governor of California from 1943 to 1953, and is the last chief justice to have served in an elected office before nomination to the Supreme Court. Warren is generally considered to be one of the most influential Supreme Court justices and political leaders in the history of the United States.

Warren was born in 1891 in Los Angeles and was raised in Bakersfield, California. After graduating from the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law, he began a legal career in Oakland. He was hired as a deputy district attorney for Alameda County in 1920 and was appointed district attorney in 1925. He emerged as a leader of the state Republican Party and won election as the Attorney General of California in 1938. In that position he supported, and was a firm proponent of, the forced removal and internment of over 100,000 Japanese Americans during World War II. In the 1942 California gubernatorial election, Warren defeated incumbent Democratic governor Culbert Olson. As the 30th Governor of California, Warren presided over a period of major growth—for the state as well as the nation. Serving from 1943 to 1953, Warren is the only governor of California to be elected for three consecutive terms.

Warren served as Thomas E. Dewey's running mate in the 1948 presidential election, but the ticket lost the election to incumbent President Harry S. Truman and Senator Alben W. Barkley in an election upset. Warren sought the Republican nomination in the 1952 presidential election, but the party nominated General Dwight D. Eisenhower. After Eisenhower won election as president, he appointed Warren as Chief Justice. A series of rulings made by the Warren Court in the 1950s helped lead to the decline of McCarthyism. Warren helped arrange a unanimous decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which ruled that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. After Brown, the Warren Court continued to issue rulings that helped bring an end to the segregationist Jim Crow laws that were prevalent throughout the Southern United States. In Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States (1964), the Court upheld the Civil Rights Act of 1964, a federal law that prohibits racial segregation in public institutions and public accommodations.

In the 1960s, the Warren Court handed down several landmark rulings that significantly transformed criminal procedure, redistricting, and other areas of the law. Many of the Court's decisions incorporated the Bill of Rights, making the protections of the Bill of Rights apply to state and local governments. Gideon v. Wainwright (1963) established a criminal defendant's right to an attorney in felony cases, and Miranda v. Arizona (1966) required police officers to give what became known as the Miranda warning to suspects taken into police custody that advises them of their constitutional protections. Reynolds v. Sims (1964) established that all state legislative districts must be of roughly equal population size, while the Court's holding in Wesberry v. Sanders (1964) required equal populations for congressional districts, thus achieving "one man, one vote" in the United States. Schmerber v. California (1966) established that forced extraction of a blood sample is not compelled testimony, illuminating the limits on the protections of the 4th and 5th Amendments and Warden v. Hayden (1967) dramatically expanded the rights of police to seize evidence with a search warrant, reversing the mere evidence rule. Furthermore, Griswold v. Connecticut (1965) established a constitutional right to privacy and struck down a state law that restricted access to contraceptives, and Loving v. Virginia (1967) struck down state anti-miscegenation laws, which had banned or otherwise regulated interracial marriage. Warren announced his retirement in 1968 and was succeeded by Appellate Judge Warren E. Burger in 1969. The Warren Court's rulings have received criticism, but have received widespread support and acclamation from both liberals and conservatives. As yet, few of the Court's decisions have been overturned.

Early life, family, and education

Warren was born in Los Angeles, California, on March 19, 1891, to Matt Warren and his wife, Crystal. Matt, whose original family name was Vaare, was born in Stavanger, Norway, in 1864, and he and his family migrated to the United States in 1866. Crystal, whose maiden name was Hernlund, was born in Hälsingland, Sweden; she and her family migrated to the United States when she was an infant. After marrying in Minneapolis, Minnesota, Mathias and Crystal settled in Southern California in 1889, where Matthias found work with the Southern Pacific Railroad. Earl Warren was the second of two children, after his older sister, Ethel. Earl did not receive a middle name; his father later commented that "when you were born I was too poor to give you a middle name." In 1896, the family resettled in Bakersfield, California, where Warren grew up. Though not an exceptional student, Warren graduated from Kern County High School in 1908.

Hoping to become a trial lawyer, Warren enrolled in the University of California, Berkeley after graduating from high school. He majored in political science and became a member of the La Junta Club, which became the Sigma Phi Society of California while Warren was attending college. Like many other students at Berkeley, Warren was influenced by the Progressive movement, and he was especially affected by Governor Hiram Johnson of California and Senator Robert M. La Follette of Wisconsin. While at Berkeley, Warren was little more than an average student who earned decent but undistinguished grades and after his third year, he entered the school's Department of Jurisprudence (now UC Berkeley School of Law). He received a Bachelor of Laws degree in 1914. Like his classmates upon graduation, Warren was admitted to the California bar without examination. After graduation, he took a position with the Associated Oil Company in San Francisco. Warren disliked working at the company and was disgusted by the corruption he saw in San Francisco, so he took a position with the Oakland law firm of Robinson and Robinson.

After the United States entered World War I in April 1917, Warren volunteered for an officer training camp, but was rejected due to hemorrhoids. Still hoping to become an officer, Warren underwent a procedure to remove the hemorrhoids, but by the time he fully recovered from the operation the officer training camp had closed. Warren enlisted in the United States Army as a private in August 1917, and was assigned to Company I of the 91st Division's 363rd Infantry Regiment at Camp Lewis, Washington. He was made acting first sergeant of the company before being sent to a three-month officer training course. After he returned to the company in May 1918 as a second lieutenant, the regiment was sent to Camp Lee, Virginia, to train draftees. Warren spent the rest of the war there and was discharged less than a month after Armistice Day, following a promotion to first lieutenant. Warren remained in the United States Army Reserve until 1934, rising to the rank of captain.

City and district attorney

In late 1918, Warren returned to Oakland, where he accepted a position as the legislative assistant to Leon E. Gray, a newly elected member of the California State Assembly. Shortly after arriving in the state capital of Sacramento, Warren was appointed as the clerk of the Assembly Judiciary Committee. After a brief stint as a deputy city attorney for Oakland, in 1920 Warren was hired as a deputy district attorney for Alameda County. By the end of 1924, Warren had become the most senior person in the department outside of the district attorney, Ezra Decoto. Though many of his professional colleagues supported Calvin Coolidge, Warren cast his vote for Progressive Party candidate Robert La Follette in the 1924 presidential election. That same year, Warren made his first foray into electoral politics, serving as the campaign manager for his friend, Republican Assemblyman Frank Anderson.

With the support of Governor Friend Richardson and publisher Joseph R. Knowland, a leader of the conservative faction of San Francisco Bay Area Republicans, Warren was appointed as the Alameda County district attorney in 1925. Warren faced a tough re-election campaign in 1926, as local Republican boss Michael Joseph Kelly sought to unseat him. Warren rejected political contributions and largely self-funded his campaign, leaving him at a financial disadvantage to Kelly's preferred candidate, Preston Higgins. Nonetheless, Warren won a landslide victory over Higgins, taking over two-thirds of the vote. When he ran for re-election again in 1930, he faced only token opposition.

Warren gained a statewide reputation as a tough, no-nonsense district attorney who fought corruption in government and ran his office in a nonpartisan manner. Warren strongly supported the autonomy of law enforcement agencies, but also believed that police and prosecutors had to act fairly. Unlike many other local law enforcement officials in the 1920s, Warren vigorously enforced Prohibition. In 1927, he launched a corruption investigation against Sheriff Burton Becker. After a trial that some in the press described as "the most sweeping exposé of graft in the history of the country," Warren won a conviction against Becker in 1930. When one of his own undercover agents admitted that he had perjured himself in order to win convictions in bootleg cases, Warren personally took charge of prosecuting the agent. Warren's efforts gained him national attention; a 1931 nationwide poll of law enforcement officials found that Warren was "the most intelligent and politically independent district attorney in the United States".

The Great Depression hit the San Francisco Bay area hard in the 1930s, leading to high levels of unemployment and a destabilization of the political order. Warren took a hard stance against labor in the buildup to the San Francisco General Strike. In Whitney v. California (1927) Warren prosecuted a woman under the California Criminal Syndicalism Act for attending a communist meeting in Oakland. In 1936, Warren faced one of the most controversial cases of his career after George W. Alberts, the chief engineer of a freighter, was found dead. Warren believed that Alberts was murdered in a conspiracy orchestrated by radical left-wing union members, and he won the conviction of union officials George Wallace, Earl King, Ernest Ramsay, and Frank Conner. Many union members argued that the defendants had been framed by Warren's office, and they organized protests of the trial.

State party leader

While continuing to serve as the district attorney of Alameda County, Warren emerged as leader of the state Republican Party. He served as the county chairman for Herbert Hoover's 1932 campaign and, after Franklin D. Roosevelt won that election, he attacked Roosevelt's New Deal policies. In 1934, Warren became chairman of the state Republican Party and he took a leading public role in opposing the gubernatorial candidacy of Democrat Upton Sinclair. Warren earned national notoriety in 1936 for leading a successful campaign to elect a slate of unpledged delegates to the 1936 Republican National Convention; he was motivated largely by his opposition to the influence of Governor Frank Merriam and publisher William Randolph Hearst. In the 1936 presidential election, Warren campaigned on behalf of the unsuccessful Republican nominee, Alf Landon.

Family and social life

After World War I, Warren lived with his sister and her husband in Oakland. In 1921, he met Nina Elisabeth Meyers (née Palmquist), a widowed, 28-year-old store manager with a three-year-old son. Nina had been born in Sweden to a Baptist minister and his wife, and her family had migrated to the United States when she was an infant. On October 4, 1925, shortly after Warren was appointed district attorney, Warren and Nina married. Their first child, Virginia, was born in 1928, and they had four more children: Earl Jr. (born 1930), Dorothy (born 1931), Nina Elisabeth (born 1933), and Robert (born 1935). Warren also adopted Nina's son, James. Warren was the father-in-law of John Charles Daly, the host of the television game show What's My Line through his daughter Virginia's marriage. Warren enjoyed a close relationship with his wife; one of their daughters later described it as "the most ideal relationship I could dream of." In 1935, the family moved to a seven-bedroom home just outside of downtown Oakland. Though the Warrens sent their children to Sunday school at a local Baptist church, Warren was not a regular churchgoer. In 1938, Warren's father, Matt, was murdered; investigators never discovered the identity of the murderer. Warren and his family moved to the state capital of Sacramento in 1943, and to Wardman-Park, a residential hotel in Washington, D.C., in 1953.

Warren was very active after 1919 in such groups as Freemasonry, the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, the Loyal Order of Moose (obtained the Pilgrim Degree of Merit, the highest award given in the fraternity) and the American Legion. Each one introduced Warren to new friends and political connections. He rose through the ranks in the Masons, culminating in his election in 1935 as the Grand Master of the Freemasons for the state of California from 1935 to 1936. Biographer Jim Newton says that Warren "thrived in the Masons because he shared their ideals, but those ideals also helped shape him, nurturing his commitment to service, deepening his conviction that society's problems were best addressed by small groups of enlightened, well-meaning citizens. Those ideals knitted together Warren's Progressivism, his Republicanism, and his Masonry."

Attorney General of California

In 1934, Warren and his allies won passage of a state ballot measure that transformed the position of Attorney General of California into a full-time office; previous officeholders had worked part-time while maintaining their own private practice. After incumbent Ulysses S. Webb announced his retirement, Warren jumped into the 1938 state attorney general election. Earlier in the 20th century, progressives had passed a state constitutional amendment allowing for "cross-filing," whereby a candidate could file to run in multiple party primaries for the same office. Warren took advantage of that amendment and ran in multiple primaries. Even though he continued to serve as chairman of the state Republican Party until April 1938, Warren won the Republican, Progressive, and, crucially, Democratic primaries for attorney general. He faced no serious opposition in the 1938 elections, even while incumbent Republican Governor Frank Merriam was defeated by Democratic nominee Culbert Olson.

Once elected, he organized state law enforcement officials into regions and led a statewide anti-crime effort. One of his major initiatives was to crack down on gambling ships operating off the coast of Southern California. Warren continued many of the policies from his predecessor Ulysses S. Webb's four decades in office. These included eugenic forced sterilizations and the confiscation of land from Japanese owners. Warren, who was a member of the outspoken anti-Asian society Native Sons of the Golden West, successfully sought legislation expanding the land confiscations. During his time as Attorney General, Warren appointed as one of his deputy attorneys general Roger J. Traynor, who was then a law professor at UC Berkeley and later became the 23rd chief justice of California, as well as one of the most influential judges of his time.

Internment of Japanese Americans

After World War II broke out in Europe in 1939, foreign policy became an increasingly important issue in the United States; Warren rejected the isolationist tendencies of many Republicans and supported Roosevelt's rearmament campaign. The United States entered World War II after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Following the attack, Warren organized the state's civilian defense program, warning in January 1942 that "the Japanese situation as it exists in this state today may well be the Achilles' heel of the entire civilian defense effort." He became a driving force behind the internment of over one hundred thousand Japanese Americans without any charges or due process.

Though the decision to intern Japanese Americans was made by General John L. DeWitt, and the internment was carried out by federal officials, Warren's advocacy played a major role in providing public justification for the internment. In particular, Warren had claimed that Japanese Americans had willfully infiltrated "every strategic spot" in California coastal and valley counties, had warned of potentially greater danger from American born ethnic Japanese than from first-generation immigrants, and asserted that although there were means to test the loyalty of a "Caucasian" that the same could not be said for ethnic Japanese. Warren further argued that the complete lack of disloyal acts among Japanese Americans in California to date indicated that they intended to commit such acts in the future. Later, Warren vigorously protested the return of released internees back into California.

By early 1944, Warren had come to regret his role in the internment of Japanese Americans, and he eventually approved of the federal government's decision to allow Japanese Americans to begin returning to California in December 1944. However, he long resisted any public expression of regret in spite of years of repeated requests from the Japanese American community.

In a 1972 oral history interview, Warren said that "I feel that everybody who had anything to do with the relocation of the Japanese, after it was all over, had something of a guilty consciousness about it, and wanted to show that it wasn't a racial thing as much as it was a defense matter". When during the interview Warren mentioned the faces of the children separated from their parents, he broke down in tears and the interview was temporarily halted. In 1974, shortly before his death, Warren privately confided to journalist and former internee Morse Saito that he greatly regretted his actions during the evacuation.

In his posthumously published memoirs, Warren fully acknowledged his error, stating that he

since deeply regretted the removal order and my own testimony advocating it, because it was not in keeping with our American concept of freedom and the rights of citizens... Whenever I thought of the innocent little children who were torn from home, school friends, and congenial surroundings, I was conscience-stricken... [i]t was wrong to react so impulsively, without positive evidence of disloyalty.

— The Memoirs of Earl Warren (1977)

Governor of California

Election

Warren frequently clashed with Governor Culbert Olson over various issues, partly because they belonged to different parties. As early as 1939, supporters of Warren began making plans for his candidacy in California's 1942 gubernatorial election. Though initially reluctant to run, Warren announced his gubernatorial candidacy in April 1942. He cross-filed in the Democratic and Republican primaries, ran without a party label, and refused to endorse candidates running for other offices. He sought to attract voters regardless of party, and stated "I can and will support President Roosevelt better than Olson ever has or ever will." Many Democrats, including Olson, criticized Warren for "put[ting] on a cloak of nonpartisanship," but Warren's attempts to appear above parties resonated with many voters. In August, Warren easily won the Republican primary, and surprised many observers by nearly defeating Olson in the Democratic primary. In November, he decisively defeated Olson in the general election, taking just under 57 percent of the vote. Warren's victory immediately made him a figure with national stature, and he enjoyed good relations with both the conservative wing of the Republican Party, led by Robert A. Taft, and the moderate wing of the Republican Party, led by Thomas E. Dewey.

Policies

Warren modernized the office of governor, and state government generally. Like most progressives, Warren believed in efficiency and planning. During World War II, he aggressively pursued postwar economic planning. Fearing another postwar decline that would rival the depression years, Governor Earl Warren initiated public works projects similar to those of the New Deal to capitalize on wartime tax surpluses and provide jobs for returning veterans. For example, his support of the Collier-Burns Act in 1947 raised gasoline taxes that funded a massive program of freeway construction. Unlike states where tolls or bonds funded highway construction, California's gasoline taxes were earmarked for building the system. Warren's support for the bill was crucial because his status as a popular governor strengthened his views, in contrast with opposition from trucking, oil, and gas lobbyists. The Collier-Burns Act helped influence passage of the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, setting a pattern for national highway construction. In the mid-1940s, Warren sought to implement a state universal health care, but he was unable to pass his plan due to opposition from the medical and business communities. In 1945, the United Nations Charter was signed in San Francisco while Warren was the governor of California. He played an important role in the United Nations Conference on International Organization from April 25 to June 26, 1945, which resulted in the United Nations Charter.

Warren also pursued social legislation. He built up the state's higher education system based on the University of California and its vast network of small universities and community colleges. After federal courts declared the segregation of Mexican schoolchildren illegal in Mendez v. Westminster (1947), Governor Warren signed legislation ending the segregation of American Indians and Asians. He sought the creation of a commission to study employment discrimination, but his plan was blocked by Republicans in the state legislature. Governor Warren stopped enforcing California's anti-miscegenation law after it was declared unconstitutional in Perez v. Sharp (1948). He also improved the hospital and prison systems. These reforms provided new services to a fast-growing population; the 1950 Census showed that California's population had grown by over 50% over the previous ten years.

Re-election campaigns

By 1946, California's economy was booming, Warren was widely popular, and he enjoyed excellent relations with the state's top Democratic officeholder, Attorney General Robert W. Kenny. At the urging of state party leaders, Kenny agreed to run against Warren in the 1946 gubernatorial election, but Kenny was reluctant to criticize his opponent and was distracted by his role in the Nuremberg trials. As in 1942, Warren refused to endorse candidates for other offices, and he sought to portray himself as an effective, nonpartisan governor. Warren easily won the Republican primary for governor and, in a much closer vote, defeated Kenny in the Democratic primary. After winning both primaries, Warren endorsed Republican William Knowland's U.S. Senate candidacy and Goodwin Knight's candidacy for lieutenant governor. Warren won the general election by an overwhelming margin, becoming the first Governor of California since Hiram Johnson in 1914 to win a second term.

Though he considered retiring after two terms, Warren ultimately chose to seek re-election in 1950, partly to prevent Knight from succeeding him. He easily won the Republican primary, but was defeated in the Democratic primary by James Roosevelt. Warren consistently led Roosevelt in general election polls and won re-election in a landslide, taking 65 percent of the vote. He was the first Governor of California elected to three consecutive terms. During the 1950 campaign, Warren refused to formally endorse Richard Nixon, the Republican nominee for the Senate. Warren disliked what he saw as Nixon's ruthless approach to politics and was wary of having a conservative rival for leadership of the state party. Despite Warren's refusal to campaign for him, Nixon defeated Democratic nominee Helen Gahagan Douglas by a decisive margin.

National politics, 1942–1952

After his election as governor, Warren emerged as a potential candidate for president or vice president in the 1944 election. Seeking primarily to ensure his status as the most prominent Republican in California, he ran as a favorite son candidate in the 1944 Republican primaries. Warren won the California primary with no opposition, but Thomas Dewey clinched the party's presidential nomination by the time of the 1944 Republican National Convention. Warren delivered the keynote address of the convention, in which he called for a more liberal Republican Party. Dewey asked Warren to serve as his running mate, but Warren was uninterested in the vice presidency and correctly believed that Dewey would be defeated by President Roosevelt in the 1944 election.

After his 1946 re-election victory, Warren began planning a run for president in the 1948 election. The two front-runners for the nomination were Dewey and Robert Taft, but Warren, Harold Stassen, Arthur Vandenberg, and General Douglas MacArthur each had significant support. Prior to the 1948 Republican National Convention, Warren attempted to position himself as a dark horse candidate who might emerge as a compromise nominee. However, Dewey won the nomination on the third ballot of the convention. Dewey once again asked Warren to serve as his running mate, and this time Warren agreed. Far ahead in the polls against President Harry S. Truman, the Democratic nominee, Dewey ran a cautious campaign that largely focused on platitudes rather than issues. Warren campaigned across the country on behalf of the ticket, but was frustrated by his inability to support specific policies. To the surprise of many observers, Truman won the election, and this became the only election Warren ever lost.

After his 1950 re-election, Warren decided that he would seek the Republican nomination in the 1952 presidential election, and he announced his candidacy in November 1951. Taft also sought the nomination, but Dewey declined to make a third run for president. Dewey and his supporters instead conducted a long campaign to draft General Dwight D. Eisenhower as the Republican presidential nominee. Warren ran in three Republican presidential primaries, but won just a handful of delegates outside of his home state. In the California primary, he defeated a challenge from Thomas H. Werdel, whose conservative backers alleged that Warren had "abandoned Republicanism and embraced the objectives of the New Deal." After Eisenhower entered the race, Warren realized that his only hope of nomination was to emerge as a compromise nominee at the 1952 Republican National Convention after a deadlock between supporters of Eisenhower and Taft.

After the primaries, Warren had the support of 80 delegates, while Eisenhower and Taft each had about 450 delegates. Though the California delegation was pledged to support Warren, many of the delegates personally favored Eisenhower or Taft. Unknown to Warren, Eisenhower supporters had promised Richard Nixon the vice presidency if he could swing the California delegation to Eisenhower. By the time of the convention, Nixon and his supporters had convinced most California delegates to switch their votes to Eisenhower after the first presidential ballot. Eisenhower won 595 votes on the first presidential ballot of the convention, just 9 short of the majority. Before the official end of the first ballot, several states shifted their votes to Eisenhower, giving him the nomination. Warren's decision to support a convention rule that unseated several contested delegations was critical to Eisenhower's victory; Eisenhower himself said that "if anyone ever clinched the nomination for me, it was Earl Warren." Nixon was named as Eisenhower's running mate, and Warren campaigned on behalf of the Republican ticket in fourteen different states. Ultimately, Eisenhower defeated Democratic nominee Adlai Stevenson II, taking 55 percent of the national popular vote. Nixon resigned from the Senate to become vice president, and Warren appointed Thomas Kuchel to the Senate seat vacated by Nixon.

Chief Justice of the United States

Appointment

After the 1952 election, President-elect Eisenhower promised that he would appoint Warren to the next vacancy on the Supreme Court of the United States. Warren turned down the position of Secretary of the Interior in the new administration, but in August 1953 he agreed to serve as the Solicitor General. In September 1953, before Warren's nomination as solicitor general was announced, Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson died. To fill the critical position of chief justice, Eisenhower first offered the position of chief justice to Thomas E. Dewey, but Dewey declined the offer. He then considered either elevating a sitting Supreme Court justice or appointing another individual with judicial experience but ultimately chose to honor his promise to appoint Warren to the first Supreme Court vacancy. Explaining Warren's qualifications for the Court, Eisenhower wrote to his brother, "Warren has had seventeen years of practice in public law, during which his record was one of remarkable accomplishment and success.... He has been very definitely a liberal-conservative; he represents the kind of political, economic, and social thinking that I believe we need on the Supreme Court."

Warren received a recess appointment in October 1953. In the winter of 1953–1954, the Senate Judiciary Committee reported him favorably by a 12–3 majority, with three southerners in James Eastland, Olin D. Johnston and Harley M. Kilgore reporting negatively. The Senate would then confirm Warren's appointment by acclamation in March 1954; unlike the future appointments of John Marshall Harlan II and Potter Stewart (who ironically would prove the most conservative members of the Warren Court) southern senators made no effort to block Warren. As of 2021, Warren is the most recent chief justice to have held statewide elected office at any point in his career and the most recent serving politician to be appointed Chief Justice. Warren was also the first Scandinavian American to be appointed to the Supreme Court.

Leadership and philosophy

When Warren was appointed, all of the other Supreme Court justices had been appointed by Presidents Franklin Roosevelt or Harry Truman, and most were committed New Deal liberal Democrats. Nonetheless, they disagreed about the role that courts should play. Felix Frankfurter led a faction that insisted upon judicial self-restraint and deference to the policymaking prerogatives of the White House and Congress. Hugo Black and William O. Douglas led the opposing faction by agreeing the Court should defer to Congress in matters of economic policy but favored a more activist role for the courts in matters related to individual liberties. Warren's belief that the judiciary must seek to do justice placed him with the Black and Douglas faction. William J. Brennan Jr. became the intellectual leader of the activist faction after he was appointed to the court by Eisenhower in 1956 and complemented Warren's political skills by the strong legal skills that Warren lacked.

As chief justice, Warren's most important prerogative was the power to assign opinions if he was in the majority. That power had a subtle but important role in shaping the Court's majority opinions, since different justices would write different opinions. Warren initially asked the senior associate justice, Hugo Black, to preside over conferences until he became accustomed to the processes of the Court. However, Warren learned quickly and soon was in fact, as well as in name, the Court's chief justice. Warren's strength lay in his public gravitas, his leadership skills, and his firm belief that the Constitution guaranteed natural rights and that the Court had a unique role in protecting those rights. His arguments did not dominate judicial conferences, but Warren excelled at putting together coalitions and cajoling his colleagues in informal meetings.

Warren saw the US Constitution as the embodiment of American values, and he cared deeply about the ethical implications of the Court's rulings. According to Justice Potter Stewart, Warren's philosophical foundations were the "eternal, rather bromidic, platitudes in which he sincerely believed" and "Warren's great strength was his simple belief in the things we now laugh at: motherhood, marriage, family, flag, and the like." The constitutional historian Melvin I. Urofsky concludes that "scholars agree that as a judge, Warren does not rank with Louis Brandeis, Black, or Brennan in terms of jurisprudence. His opinions were not always clearly written, and his legal logic was often muddled." Other scholars have also reached this conclusion.

1950s

Brown v. Board of Education

Soon after joining the Court, Warren presided over the case of Brown v. Board of Education, which arose from the NAACP's legal challenge against Jim Crow laws. The Southern United States had implemented Jim Crow laws in aftermath of the Reconstruction Era to disenfranchise African Americans and segregate public schools and other institutions. In the 1896 case of Plessy v. Ferguson, the Court had held that the Fourteenth Amendment did not prohibit segregation in public institutions if the institutions were "separate but equal." In the decades after Plessy, the NAACP had won several incremental victories, but 17 states required the segregation of public schools by 1954. In 1951, the Vinson Court had begun hearing the NAACP's legal challenge to segregated school systems but had not rendered a decision when Warren took office.

By the early 1950s, Warren had become personally convinced that segregation was morally wrong and legally indefensible. Warren sought not only to overturn Plessy but also to have a unanimous verdict. Warren, Black, Douglas, Burton, and Minton supported overturning the precedent, but for different reasons, Robert H. Jackson, Felix Frankfurter, Tom C. Clark, and Stanley Forman Reed were reluctant to overturn Plessy. Nonetheless, Warren won over Jackson, Frankfurter, and Clark, in part by allowing states and federal courts the flexibility to pursue desegregation of schools at different speeds. Warren extensively courted the last holdout, Reed, who finally agreed to join a unanimous verdict because he feared that a dissent would encourage resistance to the Court's holding. After the Supreme Court formally voted to hold that the segregation of public schools was unconstitutional, Warren drafted an eight-page outline from which his law clerks drafted an opinion, and the Court handed down its decision in May 1954. In the Deep South at the time, people could view signs claiming "Impeach Earl Warren."

Other decisions and events

In arranging a unanimous decision in Brown, Warren fully established himself as the leader of the Court. He also remained a nationally prominent figure. After a 1955 Gallup poll found that a plurality of Republican respondents favored Warren as the successor to Eisenhower, Warren publicly announced that he would not resign from the Court under any circumstance. Eisenhower seriously considered retiring after one term and encouraging Warren to run in the 1956 presidential election but ultimately chose to run after he had received a positive medical report after his heart attack. Despite that brief possibility, a split developed between Eisenhower and Warren, and some writers believe that Eisenhower once remarked that his appointment was "the biggest damn fool mistake I ever made."

Meanwhile, many Southern politicians expressed outrage at the Court's decisions and promised to resist any federal attempt to force desegregation, a strategy known as massive resistance. Although Brown did not mandate immediate school desegregation or bar other "separate but equal" institutions, most observers recognized that the decision marked the beginning of the end for the Jim Crow system. Throughout his years as chief justice, Warren succeeded in keeping decisions concerning segregation unanimous. Brown applied only to schools, but soon, the Court enlarged the concept to other state actions by striking down racial classification in many areas. Warren compromised by agreeing to Frankfurter's demand for the Court to go slowly in implementing desegregation. Warren used Frankfurter's suggestion for a 1955 decision (Brown II) to include the phrase "all deliberate speed." In 1956, after the Montgomery bus boycott, the Supreme Court affirmed a lower court's decision that segregated buses are unconstitutional. Two years later, Warren assigned Brennan to write the Court's opinion in Cooper v. Aaron. Brennan held that state officials were legally bound to enforce the Court's desegregation ruling in Brown.

In the 1956 term, the Warren Court received condemnation from right-wingers such as US Senator Joseph McCarthy by handing down a series of decisions, including Yates v. United States, which struck down laws designed to suppress communists and later led to the decline of McCarthyism. The Warren Court's decisions on those cases represented a major shift from the Vinson Court, which had generally upheld such laws during the Second Red Scare. That same year, Warren was elected to the American Philosophical Society. In 1957, he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

1960s

After the Republican Party nominated Richard Nixon in the 1960 presidential election, Warren privately supported the Democratic nominee, John F. Kennedy. They became personally close after Kennedy was inaugurated. Warren later wrote that "no American during my long life ever set his sights higher for a better America or centered his attacks more accurately on the evils and shortcomings of our society than did [Kennedy]." In 1962, Frankfurter retired and was replaced by Kennedy appointee Arthur Goldberg, which gave the liberal bloc a majority on the Court. Goldberg left the Court in 1965 but was replaced by Abe Fortas, who largely shared Goldberg's judicial philosophy. With the liberal bloc firmly in control, the Warren Court handed down a series of momentous rulings in the 1960s.

Bill of Rights

The 1960s marked a major shift in constitutional interpretation, as the Warren Court continued the process of the incorporation of the Bill of Rights in which the provisions of the first ten amendments to the US Constitution were applied to the states. Warren saw the Bill of Rights as a codification of "the natural rights of man" against the government and believed that incorporation would bring the law "into harmony with moral principles." When Warren took office, most of the provisions of the First Amendment already applied to the states, but the vast majority of the Bill of Rights applied only to the federal government. The Warren Court saw the incorporation of the remaining provisions of the First Amendment as well as all or part of the Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, and Eighth Amendments. The Warren Court also handed down numerous other important decisions regarding the Bill of Rights, especially in the field of criminal procedure.

In New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, the Supreme Court reversed a libel conviction of the publisher of the New York Times. In the majority opinion, Brennan articulated the actual malice standard for libel against public officials, which has become an enduring part of constitutional law. In Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, the Court reversed the suspension of an eighth-grade student who wore a black armband in protest of the Vietnam War. Fortas's majority opinion noted that students did not "shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate." The Court's holding in United States v. Seeger expanded those who could be classified as conscientious objectors under the Selective Service System by allowing nonreligious individuals with ethical objections to claim conscientious objector status. Another case, United States v. O'Brien, saw the Court uphold a prohibition against burning draft-cards. Warren dissented in Street v. New York in which the Court struck down a state law that prohibited the desecration of the American flag. When his law clerks asked why he dissented in the case, Warren stated, "Boys, it's the American flag. I'm just not going to vote in favor of burning the American flag." In the 1969 case of Brandenburg v. Ohio, the Court held that governments cannot punish speech unless it is "directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action."

In 1962, Engel v. Vitale held that the Establishment Clause prohibits mandatory prayer in public school. The ruling sparked a strong backlash from many political and religious leaders, some of whom called for the impeachment of Warren. Warren became a favored target of right-wing groups, such as the John Birch Society, as well as the 1964 Republican presidential nominee, Barry Goldwater. Engel, the criminal procedure cases, and the persistent criticism of conservative politicians like Goldwater and Nixon contributed to a decline in the Court's popularity in the mid- and the late 1960s. Griswold v. Connecticut had the Court strike down a state law designed to restrict access to contraception, and it established a constitutional right to privacy. Griswold later provided an important precedent for the case of Roe v. Wade, which disallowed many laws designed to restrict access to abortion.

Criminal procedure

In the early 1960s, the Court increasingly turned its attention to criminal procedure, which had traditionally been primarily a domain of the states. In Elkins v. United States (1960), Warren joined with the majority in striking down the "Silver Platter Doctrine," a loophole to the exclusionary rule that had allowed federal officials to use evidence that had been illegally gathered by state officials. The next year, in Mapp v. Ohio, the Court held that the Fourth Amendment's prohibition on "unreasonable searches and seizures" applied to state officials. Warren wrote the majority opinion in Terry v. Ohio (1968) in which the Court established that police officers may frisk a criminal suspect if they have a reasonable suspicion that the suspect is committing or is about to commit a crime. In Gideon v. Wainwright (1962), the Court held that the Sixth Amendment required states to furnish publicly funded attorneys to all criminal defendants accused of a felony and unable to afford counsel. Prior to Gideon, criminal defendants had been guaranteed the right to counsel only in federal trials and capital cases.

In Escobedo v. Illinois (1964), the Court held that the Sixth Amendment guarantees criminal suspects the right to speak to their counsel during police interrogations. Escobedo was limited to criminal suspects who had an attorney at the time of their arrest and requested to speak with that counsel. In the landmark case of Miranda v. Arizona, Warren wrote the majority opinion, which established a right to counsel for every criminal suspect and required police to give criminal suspects what became known as a "Miranda warning" in which suspects are notified of their right to an attorney and their right to silence. Warren incorporated some suggestions from Brennan, but his holding in Miranda was most influenced by his past experiences as a district attorney. Unlike many of the other Warren Court decisions, including Mapp and Gideon, Miranda created standards that went far beyond anything that had been established by any of the states. Miranda received a strong backlash from law enforcement and political leaders. Conservatives angrily denounced what they called the "handcuffing of the police."

Reapportionment (one man, one vote)

The right to vote freely for the candidate of one's choice is of the essence of a democratic society, and any restrictions on that right strike at the heart of representative government. And the right of suffrage can be denied by a debasement or dilution of the weight of a citizen's vote just as effectively as by wholly prohibiting the free exercise of the franchise.

--Chief Justice Earl Warren on the right to vote as the foundation of democracy in Reynolds v. Sims (1964).

In 1959, several residents dissatisfied with Tennessee's legislative districts brought suit against the state in Baker v. Carr. Like many other states, Tennessee had state legislative districts of unequal populations, and the plaintiffs sought more equitable legislative districts. In Colegrove v. Green (1946), the Supreme Court had declined to become involved in legislative apportionment and instead left the issue as a matter for Congress and the states. In Gomillion v. Lightfoot (1960), the Court struck down a redistricting plan designed to disenfranchise African-American voters, but many of the justices were reluctant to involve themselves further in redistricting. Frankfurter insisted that the Court should avoid the "political thicket" of apportionment and warned that the Court would never be able to find a clear formula to guide lower courts. Warren helped convince Associate Justice Potter Stewart to join Brennan's majority decision in Baker v. Carr, which held that redistricting was not a political question and so federal courts had jurisdiction over the issue. The opinion did not directly require Tennessee to implement redistricting but instead left it to a federal district court to determine whether Tennessee's districts violated the Constitution. In another case, Gray v. Sanders, the Court struck down Georgia's County Unit System, which granted disproportional power to rural counties in party primaries. In a third case, Wesberry v. Sanders, the Court required states to draw congressional districts of equal population.

In Reynolds v. Sims (1963), the chief justice wrote what biographer Ed Cray terms "the most influential of the 170 majority opinions [Warren] would write." While eight of the nine justices had voted to require congressional districts of equal population in Wesberry, some of the justices were reluctant to require state legislative districts to be of equal population. Warren indicated that the Equal Protection Clause required that state legislative districts be apportioned on an equal basis: "legislators represent people, not trees or acres. Legislators are elected by voters, not farms or cities or economic interests." His holding upheld the principle of "one man, one vote," which had previously been articulated by Douglas. After the decision, the states reapportioned their legislatures quickly and with minimal troubles. Numerous commentators have concluded reapportionment was the Warren Court's great "success story."

Civil rights

Civil rights continued to be a major issue facing the Warren Court in the 1960s. In Peterson v. Greenville (1963), Warren wrote the Court's majority opinion, which struck down local ordinances that prohibited restaurants from serving black and white individuals in the same room. Later that decade, the Court upheld the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States. The Court held that the Commerce Clause empowered the federal government to prohibit racial segregation in public accommodations like hotels. The ruling effectively overturned the 1883 Civil Rights Cases in which the Supreme Court had held that Congress could not regulate racial discrimination by private businesses. The Court upheld another landmark civil rights act, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, by holding that it was valid under the authority provided to Congress by the Fifteenth Amendment.

In 1967, Warren wrote the majority opinion in the landmark case of Loving v. Virginia in which the Court struck down state laws banning interracial marriage. Warren was particularly pleased by the ruling in Loving since he had long regretted that the Court had not taken up the similar case of Naim v. Naim in 1955. In Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections (1966), the Court struck down poll taxes in state elections. In another case, Bond v. Floyd, the Court required the Georgia legislature to seat the newly elected legislator Julian Bond; members of the legislature had refused to seat Bond because he opposed the Vietnam War.

Warren Commission

Shortly after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the newly sworn-in president, Lyndon B. Johnson, convinced Warren to serve as the head of a bipartisan commission tasked with investigating the assassination. From December 1963 to October 1964, Warren simultaneously served as chief justice of the United States and chairman of the Warren Commission.

At the start of the investigation, Warren decided to hire the commission's legal staff from outside the government to avoid any improper influence on their work. Warren appointed Lee Rankin as general counsel and worked closely with Rankin and his assistants, Howard P. Willens and Norman Redlich, to recruit staff lawyers, supervise their investigation and publish the Commission's report. To avoid the confusion and duplication of parallel investigations, Warren convinced the Texas authorities to defer any local inquiry into the assassination.

Warren was personally involved in several aspects of the investigation. He supervised four days of testimony by Lee Harvey Oswald's widow, Marina Oswald, and was widely criticized for telling the press that, although her testimony would be publicly disclosed, "it might not be in your lifetime." He attended the closed-door interview of Jacqueline Kennedy and insisted on participating in the deposition of Jack Ruby in Dallas, where he visited the book depository. Warren also participated in the investigation of Kennedy's medical treatment and autopsy. At Robert Kennedy's insistence, Warren handled the unwelcome task of reviewing the autopsy photos alone. Because the photos were so gruesome, Warren decided that they should not be included in the Commission's records.

Warren closely supervised the drafting of the Commission's report. He wanted to ensure that Commission members had ample opportunity to evaluate the staff's work and to make their own judgments about important conclusions in the report. He insisted that the report should be unanimous and so he compromised on a number of issues to get all the members to sign the final version. Although a reenactment of the assassination "produced convincing evidence" supporting the single-bullet theory, the Commission decided not to take a position on the single-bullet theory. The Commission unanimously concluded that the assassination was the result of a single individual, Lee Harvey Oswald, who acted alone.

The Warren Commission was an unhappy experience for the chief justice. As Willens recalled, "One can't say too much about the Chief's sacrifice. The work was a drain on his physical well-being." However, Warren always believed that the Commission's primary conclusion, that Oswald acted alone, was correct. In his memoirs, Warren wrote that Oswald was incapable of being the key operative in a conspiracy, and that any high-level government conspiracy would inevitably have been discovered. Newsweek magazine quoted Warren saying that, if he handled the Oswald case as a district attorney, "I could have gotten a conviction in two days and never heard about the case again." Warren wrote that "the facts of the assassination itself are simple, so simple that many people believe it must be more complicated and conspiratorial to be true." Warren told the Commission staff not to worry about conspiracy theories and other criticism of the report because “history will prove us right.”

Retirement

By 1968, Warren was ready to retire from the Court. He hoped to travel the world with his wife, and he wanted to leave the bench before he suffered a mental decline, something that he perceived in both Hugo Black and William Douglas. He also feared that Nixon would win the 1968 presidential election and appoint a conservative successor if Warren left the Court later. On 13 June 1968, Warren submitted his letter of resignation to President Johnson (who made it official on 21 June), effective upon the confirmation of a successor. In an election year, confirmation of a successor was not assured; after Warren announced his retirement, about half of the Senate Republican caucus pledged to oppose any Supreme Court appointment prior to the election.

Johnson nominated Associate Justice Fortas, a personal friend and adviser to the president, as Warren's successor, and nominated federal appellate judge Homer Thornberry to succeed Fortas. Republicans and Southern Democrats joined to scuttle Fortas's nomination. Their opposition centered on criticism of the Warren Court, including many decisions that had been handed down before Fortas joined the Court, as well as ethical concerns related to Fortas's paid speeches and closeness with Johnson. Though the majority of the Senate may have favored the confirmation of Fortas, opponents conducted a filibuster, which blocked the Senate from voting on the nomination, and Johnson withdrew the nomination. In early 1969, Warren learned that Fortas had made a secret lifetime contract for $20,000 a year to provide private legal advice to Louis Wolfson, a friend and financier in deep legal trouble. Warren immediately asked Fortas to resign, which he did after some consideration.

Nixon defeated Hubert Humphrey in the 1968 presidential election and took office in January 1969. Though reluctant to be succeeded by a Nixon appointee, Warren declined to withdraw his letter of resignation. He believed that withdrawing the letter would be "a crass admission that he was resigning for political reasons." Nixon and Warren jointly agreed that Warren would retire in June 1969 to ensure that the Court would have a chief justice throughout the 1968 term and to allow Nixon to focus on other matters in the first months of his presidency. Nixon did not solicit Warren's opinion regarding the next chief justice and ultimately appointed the conservative federal appellate judge Warren E. Burger. Warren later regretted his decision to retire and reflected, "If I had ever known what was going to happen to this country and this Court, I never would have resigned. They would have had to carry me out of there on a plank." In addition, he later remarked on his retirement and on the Warren Court, "I would like the Court to be remembered as the people's court."

Final years and death

After stepping down from the Court, Warren began working on his memoirs and took numerous speaking engagements. He also advocated for an end to the Vietnam War and the elimination of poverty. He avoided publicly criticizing the Burger Court, but was privately distressed by the Court's increasingly conservative holdings. He closely followed investigations into the Watergate scandal, a major political scandal that stemmed from a break-in of the Democratic National Committee's headquarters and the Nixon administration's subsequent attempts to cover up that break-in. Warren continued to hold Nixon in low regard, privately stating that Nixon was "perhaps the most despicable president that this country has ever had."

Five years into retirement, Warren died due to cardiac arrest at Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, D.C., at 8:10 p.m. on July 9, 1974, at the age of 83. He had been hospitalized since July 2 due to congestive heart failure and coronary insufficiency. On that same day, he was visited by Justices Brennan and Douglas, until 5:30 p.m. Warren could not resist asking his friends whether the Court would order President Nixon to release the sixty-four tapes demanded by the Watergate investigation. Both justices assured him that the court had voted unanimously in United States v. Nixon for the release of the tapes. Relieved, Warren died just a few hours later, safe in the knowledge that the Court he had so loved would force justice on the man who had been his most bitter foe.

Warren had his wife and one of his daughters, Nina Elizabeth Brien, at his bedside when he died. After he lay in repose in the Great Hall of the United States Supreme Court Building, his funeral was held at Washington National Cathedral, and he was interred at Arlington National Cemetery.

Legacy

Historical reputation

Warren is generally considered to be one of the most influential U.S. Supreme Court justices, as well as political leaders in the history of the United States. The Warren Court has been recognized by many to have created a liberal "Constitutional Revolution", which embodied a deep belief in equal justice, freedom, democracy, and human rights. In July 1974, after Warren died, the Los Angeles Times commented that "Mr. Warren ranked with John Marshall and Roger Taney as one of the three most important chief justices in the nation's history." In December 2006, The Atlantic cited Earl Warren as the 29th most influential person in the history of the United States and the second most influential Chief Justice, after John Marshall. In September 2018, The Economist named Warren as "the 20th century's most consequential American jurist" and one of "the 20th century's greatest liberal jurists".

President Harry S. Truman wrote in his tribute to Warren, which appeared in the California Law Review in 1970, "[t]he Warren record as Chief Justice has stamped him in the annals of history as the man who read and interpreted the Constitution in relation to its ultimate intent. He sensed the call of the times-and he rose to the call." Supreme Court Associate Justice William O. Douglas wrote, in the same article, "in my view [Warren] will rank with Marshall and Hughes in the broad sweep of United States history". According to biographer Ed Cray, Warren was "second in greatness only to John Marshall himself in the eyes of most impartial students of the Court as well as the Court's critics." Pulitzer Prize winner Anthony Lewis described Warren as "the closest thing the United States has had to a Platonic Guardian". In 1958, Martin Luther King Jr. sent one copy of his newly published book, Stride Toward Freedom, to Chief Justice Earl Warren, writing on the first free end page: "To: Justice Earl Warren. In appreciation for your genuine good-will, your great humanitarian concern, and your unswerving devotion to the sublime principles of our American democracy. With warm Regards, Martin L. King Jr." The book remained with Warren's family until 2015, when it was auctioned online for US$49,335 (including the buyer's premium).

Warren's critics found him a boring person. Dennis J. Hutchinson wrote: "Although Warren was an important and courageous figure and although he inspired passionate devotion among his followers...he was a dull man and a dull judge." Conservatives attacked the Warren Court's rulings as inappropriate and have called for courts to be deferential to the elected political branches. In his 1977 book Government by Judiciary, originalist and legal scholar Raoul Berger accuses the Warren Court of overstepping its authority by interpreting the 14th Amendment in a way contrary to the original intent of its draftsmen and framers in order to achieve results that it found desirable as a matter of public policy.

Overall, law professor Justin Driver divides interpretations of the Warren Court into three main groups: conservatives such as Robert Bork who attack the Court as "a legislator of policy...that was not theirs to make", liberals such as Morton Horwitz who strongly approve of the Court, and liberals such as Cass Sunstein who largely approve of the Court's overall legacy but believe that it went too far in making policy in some cases. Driver offers a fourth view, arguing that the Warren Court took overly conservative stances in such cases as Powell v. Texas and Hoyt v. Florida. As for the legacy of the Warren Court, Chief Justice Burger, who succeeded Earl Warren in 1969, proved to be quite ineffective at consolidating conservative control over the Court, so the Warren Court legacy continued in many respects until about 1986, when William Rehnquist became chief justice and took firmer control of the agenda. Even the more conservative Rehnquist Court refrained from expressly overturning major Warren Court cases such as Miranda, Gideon, Brown v. Board of Education, and Reynolds v. Sims. On occasion, the Rehnquist Court expanded Warren Court precedents, such as in Bush v. Gore, where the Rehnquist Court applied the principles of 1960s voting rights cases to invalidate Florida's recount in the 2000 U.S. presidential election.

Memorials and honors

Earl Warren was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom posthumously in 1981. He was also honored by the United States Postal Service with a 29¢ Great Americans series postage stamp. In December 2007, Warren was inducted into the California Hall of Fame. An extensive collection of Warren's papers, including case files from his Supreme Court service, is located at the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. Most of the collection is open for research.

On the campus of the University of California, Berkeley, Warren's alma mater, "Earl Warren Hall" is named after him. In addition, the UC Berkeley School of Law has established "The Chief Justice Earl Warren Institute on Race, Ethnicity and Diversity", or "Warren Institute" for short, in memory of Earl Warren, while the "Warren Room" inside the Law Building was also named in his honor.

In 2016 the United States Navy named the support ship USNS Earl Warren in his honour.

A number of governmental and educational institutions have been named for Warren:

- The Earl Warren Building, the headquarters of the Supreme Court of California in San Francisco

- The Earl Warren chapter of the American Inns of Court, Alameda County, California

- The Warren Freeway, the portion of California State Route 13 in Alameda County

Earl Warren College, University of California, San Diego - In 1977, Fourth College, one of the seven undergraduate colleges at the University of California, San Diego, was renamed Earl Warren College in his honor, and the Earl Warren Bill of Rights Project at UCSD is also named in his honor.

- Warren High School, Downey, California

- Earl Warren High School, San Antonio, Texas

- Warren Hall, Bakersfield High School (the high school Warren attended)

- Warren Junior High School, Bakersfield, California (Warren's hometown)

- Earl Warren Middle School, Solana Beach, California

- Warren Elementary School, Garden Grove, California

- Earl Warren Elementary School, Lake Elsinore, California

- The Earl Warren Showgrounds in Santa Barbara, California