Child discipline is the methods used to prevent future unwanted behaviour in children. The word discipline is defined as imparting knowledge and skill, in other words, to teach. In its most general sense, discipline refers to systematic instruction given to a disciple. To discipline means to instruct a person to follow a particular code of conduct.

Discipline is used by parents to teach their children about expectations, guidelines and principles. Child discipline can involve rewards and punishments to teach self-control, increase desirable behaviors and decrease undesirable behaviors. While the purpose of child discipline is to develop and entrench desirable social habits in children, the ultimate goal is to foster particular judgement and morals so the child develops and maintains self-discipline throughout the rest of their life.

Because the values, beliefs, education, customs and cultures of people vary so widely, along with the age and temperament of the child, methods of child discipline also vary widely. Child discipline is a topic that draws from a wide range of interested fields, such as parenting, the professional practice of behavior analysis, developmental psychology, social work, and various religious perspectives. In recent years, advances in the understanding of attachment parenting have provided a new background of theoretical understanding and advanced clinical and practical understanding of the effectiveness and outcome of parenting methods.

There has been debate in recent years over the use of corporal punishment for children in general, and increased attention to the concept of "positive parenting" where desirable behavior is encouraged and rewarded. The goal of positive discipline is to teach, train and guide children so that they learn, practice self-control and develop the ability to manage their emotions, and make desired choices regarding their personal behavior.

Cultural differences exist among many forms of child discipline. Shaming is a form of discipline and behavior modification. Children raised in different cultures experience discipline and shame in various ways. This generally depends on whether the society values individualism or collectivism.

History

Historical research suggests that there has been a great deal of individual variation in methods of discipline over time.

Medieval times

Nicholas Orme of the University of Exeter argues that children in medieval times were treated differently from adults in legal matters, and the authorities were as troubled about violence to children as they were to adults. In his article, Childhood in Medieval England, he states, "Corporal punishment was in use throughout society and probably also in homes, although social commentators criticized parents for indulgence towards children rather than for harsh discipline." Salvation was the main goal of discipline, and parents were driven to ensure their children a place in heaven. In one incident in early 14th-century London, neighbors intervened when a cook and clerk were beating a boy carrying water. A scuffle ensued and the child's tormentors were subdued. The neighbors did not even know the boy, but they firmly stood up for him even when they were physically attacked, and they stood by their actions when the cook and clerk later sued for damages.

Colonial times

During colonial times in the United States, parents were able to provide enjoyments for their children in the form of toys, according to David Robinson, writer for the Colonial Williamsburg Journal. Robinson notes that even the Puritans permitted their young children to play freely. Older children were expected to swiftly adopt adult chores and accountabilities, to meet the strict necessities of daily life. Harsh punishments for minor infractions were common. Beatings and other forms of corporal punishment occurred regularly; one legislator even suggested capital punishment for children's misbehavior.

Pre-Civil War and Post-Civil War times

According to Stacey Patton, corporal punishment in African American families has its roots in punishment meted out by parents and family members during the era of slavery in the United States. Europeans would use physical discipline on their children, whereas she states that it was uncommon in West African and Indigenous North American societies and only became more prevalent as their lives grew more difficult due to slavery and genocide. As such, Patton argues that traditional parenting styles were not preserved due to the "violent suppression of West African cultural practices". Parents were expected and pressured to teach their children to behave in a certain way in front of white people, as well as to expect the physical, sexual, and emotional violence and dehumanizing actions that typically came with slavery. While the Emancipation Proclamation ended the institution of slavery, in the south many expected former slaves to conform to the prior expectations of deference and demeanor. Patton states that black parents continued to use corporal punishment with their children out of fear that doing otherwise would put them and their family at risk of violence and discrimination, a form of parenting that she argues is still common today.

Biblical views

The Book of Proverbs mentions the importance of disciplining children, as opposed to leaving them neglected or unruly, in several verses. Interpretation of these verses varies, as do many passages from the Bible, from literal to metaphorical. The most often paraphrased is from Proverbs 13:24, "He that spareth his rod hateth his son: but he that loveth him chasteneth him betimes." (King James Version.) Other passages that mention the 'rod' are Proverbs 23:14, "Thou shalt beat him with the rod, and shalt deliver his soul from hell," and Proverbs 29:15, "The rod and reproof give wisdom: but a child left to himself bringeth his mother to shame."

Although the Bible's lessons have been paraphrased for hundreds of years, the modern phrase, "Spare the rod and spoil the child," was coined by Samuel Butler, in Hudibras, a mock heroic narrative poem published in 1663. The Contemporary English Version of Proverbs 13:24 is: 'If you love your children you will correct them; if you don't love them, you won't correct them'.

Medieval views

The primary guidelines followed by medieval parents in training their children were from the Bible. Scolding was considered ineffectual, and cursing a child was a terrible thing. In general, the use of corporal punishment was as a disciplinary action taken to shape behavior, not a pervasive dispensing of beatings for no reason. Corporal punishment was undoubtedly the norm. The medieval world was a dangerous place, and it could take harsh measures to prepare a child to live in it. Pain was the medieval way of illustrating that actions had consequences.

Influence of John Locke

In his 1690 Essay Concerning Human Understanding English physician and philosopher John Locke argued that the child resembled a blank tablet (tabula rasa) at birth, and was not inherently full of sin. In his 1693 Some Thoughts Concerning Education he suggested that the task of the parent was to build in the child the strong body and habits of mind that would allow the capacity of reason to develop, and that parents could reward good behavior with their esteem and punish bad behavior with disgrace – the withdrawal of parental approval and affection - as opposed to beatings.

The twentieth century

In the early twentieth century, child-rearing experts abandoned a romantic view of childhood and advocated formation of proper habits to discipline children. A 1914 U.S. Children's Bureau pamphlet, Infant Care, urged a strict schedule and admonished parents not to play with their babies. John B. Watson's 1924 Behaviorism argued that parents could train malleable children by rewarding good behavior and punishing bad, and by following precise schedules for food, sleep, and other bodily functions.

Although such principles began to be rejected as early as the 1930s, they were firmly renounced in the 1946 best-seller Baby and Child Care, by pediatrician Benjamin Spock, which told parents to trust their own instincts and to view the child as a reasonable, friendly human being. Dr. Spock revised his first edition to urge more parent-centered discipline in 1957, but critics blamed his popular book for its permissive attitude during the youth rebellions of the 1960s and 1970s.

In the last half of the century, Parent Management Training was developed and found to be effective in reducing child disruptive behavior in randomized controlled trials.

Conservative backlash

Following the permissive trend of the 1960s and early 1970s, American evangelical Christian James Dobson sought the return of a more conservative society and advocated spanking of children up to age eight. Dobson's position is controversial. As early as 1985, The New York Times stated that "most child-care experts today disapprove of physical punishment."

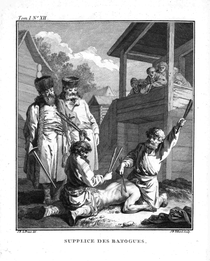

Corporal punishment

Corporal punishment of minors in the United States

In many cultures, parents have historically had the right to spank their children. A 2006 retrospective study in New Zealand, showed that physical punishment of children remained quite common in the 1970s and 1980s, with 80% of the sample reporting some kind of corporal punishment from parents, at some time during childhood. Among this sample, 29% reported being hit with an empty hand. However 45% were hit with an object, and 6% were subjected to serious physical abuse. The study noted that abusive physical punishment tended to be given by fathers and often involved striking the child's head or torso instead of the buttocks or limbs.

Attitudes have changed in recent years, and legislation in some countries, particularly in continental Europe, reflect an increased skepticism toward corporal punishment. As of December 2017, domestic corporal punishment has been outlawed in 56 countries around the world, most of them in Europe and Latin America, beginning with Sweden in 1966. Official figures show that just 10 percent of Swedish children had been spanked or otherwise struck by their parents by 2010, compared to more than 90 percent in the 1960s. The Swedish law does not actually lay down any legal punishment for smacking but requires social workers to support families with problems.

A 2013 study by Murray A. Straus at the University of New Hampshire found that children across numerous cultures who were spanked committed more crimes as adults than children who were not spanked, regardless of the quality of their relationship to their parents.

Even as corporal punishment became increasingly controversial in North America, Britain, Australia and much of the rest of the English-speaking world, limited corporal punishment of children by their parents remained lawful in all 50 states of the United States. It was not until 2012 that Delaware became the first state to pass a statute defining "physical injury" to a child to include "any impairment of physical condition or pain."

Cultural differences

A number of authors have emphasized the importance of cultural differences in assessing disciplinary methods. Clinical psychologist Diana Baumrind argues that "The cultural context critically determines the meaning and therefore the consequences of physical discipline...".

Child discipline is often affected by cultural differences. Many Eastern countries typically emphasize beliefs of collectivism in which social conformity and the interests of the group are valued above the individual. Families that promote collectivism will frequently employ tactics of shaming in the form of social comparisons and guilt induction in order to modify behavior. A child may have their behavior compared to that of a peer by an authority figure in order to guide their moral development and social awareness. Many Western countries place an emphasis on individualism. These societies often value independent growth and self esteem. Disciplining a child by contrasting them to better-behaved children is contrary to the individualistic societies value of nurturing children's self-esteem. These children of individualistic societies are more likely to feel a sense of guilt when shame is used as a form of behavior correction. For the collectivist societies, shaming corresponds with the value of promoting self improvement without negatively affecting self esteem.

Parenting styles

There are different parenting styles which parents use to discipline their children. Four types have been identified: authoritative parents, authoritarian parents, indulgent parents, and indifferent parents.

Authoritative parents are parents who use warmth, firm control, and rational, issue-oriented discipline, in which emphasis is placed on the development of self-direction. They place a high value on the development of autonomy and self-direction, but assume the ultimate responsibility for their child's behavior.

Authoritarian parents are parents who use punitive, absolute, and forceful discipline, and who place a premium on obedience and conformity. These parents believe it is their responsibility to provide for their children and that their children have little to no right to tell the parent how best to do this. Adults are expected to know from experience what is really in the child's best interest and so adult views are allowed to take precedence over child desires. Children are perceived to know what they want but not necessarily what is best for them.

Indulgent parents are parents who are characterized by responsiveness but low demandingness, and who are mainly concerned with the child's happiness. They behave in an accepting, benign, and somewhat more passive way in matters of discipline.

Indifferent parents are parents who are characterized by low levels of both responsiveness and demandingness. They try to do whatever is necessary to minimize the time and energy they must devote to interacting with their child. In extreme cases, indifferent parents may be neglectful. They ask very little of their children. For instance, they rarely assign their children chores. They tend to be relatively uninvolved in their children's lives. They believe their children should live their own lives, as free of parental control as possible.

Connected parents are parents who want to improve the way in which they connect with their children using an empathetic approach to challenging or even tumultuous relationships. Using the 'CALM' technique, by Jennifer Kolari, parents recognize the importance of empathy and aspire to build capacity in their children in hopes of them becoming confident and emotionally resilient. The CALM acronym stands for: Connect emotionally, match the Affect of the child, Listen to what your child is saying and Mirror their emotion back to show understanding.

Non-physical discipline

Non-physical discipline consists of both punitive and non-punitive methods but does not include any forms of corporal punishment such as hitting or spanking. Thus, no single method is considered to be for exclusive use. Non-Physical discipline is used in the concerted cultivation style of parenting that comes from the middle and upper class. Concerted cultivation is the method of parenting that includes heavy parental involvement, and use reasoning and bargaining as disciplinary methods.

Time-outs

A common method of child discipline is sending the child away from the family or group after misbehavior. Children may be told to stand in the corner ("corner time") or may be sent to their rooms for a period of time (room time). A time-out involves isolating or separating a child for a few minutes and is intended to give an over-excited child time to calm down.

Alternatively, time-outs have been recommended as a time for parents to separate feelings of anger toward the child for their behavior and to develop a plan for discipline.

If an individual decides to use the time-out with a child as a discipline strategy, the individual must be unemotional and consistent with the undesired behavior. Along with taking into consideration the child's temperament, professionals have recommended that the length of the time-out also should depend on the age of the child. For example, the time-out should last one minute per year of the child's age, so if the child is five years old, the time-out should go no longer than five minutes. However, research results have suggested that this does not improve its effectiveness.

Time-outs have been recommended by researchers and professional organizations on the basis of a large body of research. However, several anti-discipline experts do not recommend the use of any form of punishment, including time-outs. These authors include Thomas Gordon, Alfie Kohn, and Aletha Solter.

Grounding

Another common method of discipline used for, usually, preteens and teenagers, is restricting the child's freedom of movement, optionally compounded by restricting activities. Examples of restriction of movement would be confinement to the yard, to the house, or to just the bedroom and restroom, excepting for required activities, such as attending school or religious services, going to work, obtaining healthcare, performing chores, etc. Examples of restriction of activities would be disallowing visits by friends, forbidding use of a telephone and other means of communications, prohibiting games and electronic entertainment, taking away books and toys, and forbidding watching television and listening to music.

Hotsaucing

"Hotsaucing", or "Hot saucing", is the practice of putting hot sauce in the child's mouth, which can be considered a form of child abuse. Some pediatricians, psychologists and experts on childcare strongly recommend against this practice.

Former child star Lisa Whelchel advocates hot saucing in her parenting book Creative Correction. In the book, Whelchel claims the practice is more effective and humane than traditional corporal punishments, such as spanking; she repeated this opinion when promoting her book on Good Morning America, where she said in raising her own child she found the technique successful where other measures had failed. Whelchel's book recommends using only "tiny" amounts of hot sauce, and lists alternatives such as lemon juice or vinegar.

The practice had also been suggested in a 2001 article in Today's Christian Woman magazine, where only "a drop" is suggested, and alternative substances are listed.

While these publications are credited with popularizing hot saucing, the practice is believed by some to come from Southern United States culture. It is well known among pediatricians, psychologists and child welfare professionals. If a child is allergic to any of the ingredients in a hot sauce, it can cause swelling of the child's tongue and esophagus, presenting a choking hazard.

Scolding

Scolding involves reproving or criticizing a child's negative behavior and/or actions.

Some research suggests that scolding is counter-productive because parental attention (including negative attention) tends to reinforce behavior.

Non-punitive discipline

While punishments may be of limited value in consistently influencing rule-related behavior, non-punitive discipline techniques have been found to have greater impact on children who have begun to master their native language. Non-punitive discipline (also known as empathic discipline and positive discipline) is an approach to child-rearing that does not use any form of punishment. It is about loving guidance, and requires parents to have a strong relationship with their child so that the child responds to gentle guidance as opposed to threats and punishment. According to Dr. Laura Markham, the most effective discipline strategy is to make sure your child wants to please you.

Non-punitive discipline also excludes systems of "manipulative" rewards. Instead, a child's behavior is shaped by "democratic interaction" and by deepening parent-child communication. The reasoning behind it is that while punitive measures may stop the problem behavior in the short term, by themselves they do not provide a learning opportunity that allows children the autonomy to change their own behavior. Punishments such as time-outs may be seen as banishment and humiliation. Consequences as a form of punishment are not recommended, but natural consequences are considered to be possibly worthwhile learning experiences provided there is no risk of lasting harm.

Positive discipline is both non-violent discipline and non-punitive discipline. Criticizing, discouraging, creating obstacles and barriers, blaming, shaming, using sarcastic or cruel humor, or using physical punishment are some negative disciplinary methods used with young children. Any parent may occasionally do any of these things, but doing them more than once in a while may lead to low self-esteem becoming a permanent part of the child's personality.

Authors in this field include Aletha Solter, Alfie Kohn, Pam Leo, Haim Ginott, Thomas Gordon, Lawrence J. Cohen, and John Gottman.

Essential aspects

In the past, harsh discipline was the norm for families in society. However, research by psychologists has brought about new forms of effective discipline. Positive discipline is based on minimizing the child's frustrations and misbehavior rather than giving punishments. The main focus in this method is the "Golden Rule", treat others the way you want to be treated. Parents follow this when disciplining their children because they believe that their point will reach the children more effectively rather than traditional discipline. The foundation of this style of discipline is encouraging children to feel good about themselves and building the parent's relationship with the child so the child wants to please the parent. In traditional discipline, parents would instill fear in their child by using shame and humiliation to get their point across. In positive discipline the parents avoid negative treatment and focus on the importance of communication and showing unconditional love. Feeling loved, important and well liked has positive and negative effects on how a child perceives themselves. The child will feel important if the child feels well liked and loved by a person. Other important aspects are reasonable and age-appropriate expectations, feeding healthy foods and providing enough rest, giving clear instructions which may need to be repeated, looking for the causes of any misbehavior and making adjustments, and building routines. Children are helped by knowing what is happening in their lives. Having some predictability about their day without necessarily being regimental may help reduce frustration and misbehavior.

Methods

Praise and rewards

B. F. Skinner argued that simply giving the child spontaneous expressions of appreciation or acknowledgement when they are not misbehaving will act as a reinforcer for good behavior. Focusing on good behavior versus bad behavior will encourage appropriate behavior in the given situation. According to Skinner, past behavior that is reinforced with praise is likely to repeat in the same or similar situation.

In operant conditioning, schedules of reinforcement are an important component of the learning process. When and how often we reinforce a behavior can have a dramatic impact on the strength and rate of the response. A schedule of reinforcement is basically a rule stating which instances of a behavior will be reinforced. In some case, a behavior might be reinforced every time it occurs. Sometimes, a behavior might not be reinforced at all. Either positive reinforcement or negative reinforcement might be used, depending on the situation. In both cases, the goal of reinforcement is always to strengthen the behavior and increase the likelihood that it will occur again in the future. In real-world settings, behaviors are probably not going to be reinforced each and every time they occur. For situations where you are purposely trying to train and reinforce an action, such as in the classroom, in sports or in animal training, you might opt to follow a specific reinforcement schedule. As you'll see below, some schedules are best suited to certain types of training situations. In some cases, training might call for starting out with one schedule and switching to another once the desired behavior has been taught.

- Example of operant conditioning

Positive reinforcement: Whenever they are being cooperative, solves things non-aggressively, immediately reward those behaviors with praise, attention, goodies.

Punishment: If acting aggressively, give immediate, undesired consequence (send to corner; say "NO!" and couple with response cost).

Response cost: Most common would be "time-out". Removing sources of attention by placing in an environment without other people.

Negative reinforcement: One example would be to couple negative reinforcement with response cost—after some period of time in which he has acted cooperatively or calmly while in the absence of others, can bring him back with others. Thus, taking away the isolation should reinforce the desired behavior (being cooperative).

Extinction: Simply ignoring behaviors should lead to extinction. Note: that initially when ignored, can expect an initial increase in the behavior—a very trying time in situations such as a child that is acting out.

It is common for children who are otherwise ignored by their parents to turn to disruptive behaviour as a way of seeking attention. An example is a child screaming for attention. Parents often inadvertently reward the bad behavior by immediately giving them the attention, thereby reinforcing it. On the other hand, parents may wait until the child calms down and speaks politely, then reward the more polite behavior with the attention.

Natural consequences

Natural consequences involve children learning from their own mistakes. In this method, the parent's job is to teach the child which behaviors are inappropriate. In order to do this, parents should allow the child to make a mistake and let them experience the natural results from their behavior. For instance, if a child forgets to bring his lunch to school, he will find himself hungry later. Using natural consequences would be indicative of the theory of accomplishment of natural growth, which is the parenting style of the working class and poor. The accomplishment of natural growth focuses on separation between children and family. Children are given directives and expected to carry them out without complaint or delay. Children are responsible for themselves during their free time, and the parent's main concern is caring for the children's physical needs.

Research

Non-violent discipline options

A systematic overview of evidence on non-violent discipline options conducted by Karen Quail and Catherine Ward was published in 2020.This meta study reviewed 223 systematic reviews covering data from 3,921 primary studies, and available research evidence was summarized for over 50 discipline tools.

Non-violent parenting tools were defined as any skills "which can be used to address a child's resistance, lack of cooperation, problem behavior or dysregulation, or to teach and support appropriate behavior". This is distinguished from a coercive approach, "in which the adult tries to force a certain reaction from the child using threats, intimidation and punishment." Coercive approaches have been found to increase child aggression and conduct problems.

Quail and Ward observed that information on discipline skills on the internet and in parenting books is limited and often inaccurate and misleading. "There is advice against time-outs or praise and rewards, when in fact these are evidence-supported skills which, used appropriately, have positive effects on behavior.". They highlight the need for an evidence-based toolkit of individual skills from which parents and teachers can choose techniques that best suit the situation and fit with their cultural norms. The meta-study found a wide range of evidence-supported nonviolent discipline tools, many of which have been found effective with severe problem behavior. Quail organized these into a Peace Discipline model supported by a toolkit of techniques.

A few of the specific tools showing positive effects include the following.

- Good, warm, open communication between parent and child, especially the kind that encourages child disclosure. This could imply the use of skills such as active listening and open-ended questions, and the absence of judgment, criticism or other reactions on the part of the parent that would shut child disclosure down.

- Time-in. Time with parents during which there is physical touch and ample expressions of care, compassion and praise.

- Parental monitoring. It has been shown that aside from supervision or surveillance, child disclosure is an important part of monitoring. This underlines the importance of a good parent-child relationship, with warm, open communication and good listening skills.

- Setting expectations (rules).

- Distracting a child with an acceptable toy, object, or activity.

- Modelling the behavior parents wish to see.

- Prompting or reminding a child to do something.

- Feedback on behavior.

- Praise.

- Rewards.

- Goal-setting with the child.

- Promoting self-management.

- Promoting problem-solving skills. This can be done by collaborating with children to find solutions for discipline problems e.g. having a meeting with children to discuss the problem of them getting to school late every morning, brainstorming possible solutions with them, and together choosing the solution that would work best

- Giving appropriate choices.

- Time-out. There are two kinds, exclusionary (e.g. the child must stay in their room for a few minutes if they lash out and hurt someone) and non-exclusionary (e.g. a time-out from a toy or cell phone if they are fighting over the toy or abusing phone privileges). Time-outs are most often used for aggression or non-compliance. Exclusionary timeouts may be necessary in the case of aggression, but in other situations either kind has been shown to work. The wide variation in timeouts that work suggests that parents can tailor timeouts according to what feels right for them and what best suits their child's needs. Some examples are: time-out in a room, timeout from a toy, screen time, attention, or from playing in a game they are disrupting. Timeouts in the studies reviewed were implemented calmly, not in a harsh or rejecting manner, and work better in a context where interaction between parent and child is usually of good quality (see time-in).

- Emotion Coaching or teaching children emotional communication skills. This involves the parents developing an emotional vocabulary for themselves and their children, and learning to become comfortable using emotional experiences as teaching and connection opportunities.

Other, more technical tools include behavior contracts, utilizing cost, group contingencies, and restorative justice interventions.

Quail and Ward suggest that parental attunement is a key parent-skill to effectively use positive parenting tools. Attunement involves giving focused attention to the child's needs behavioral signals, and matching an appropriate choice of discipline tool. They use this example as an illustration: "rewards undermined intrinsic motivation for children who were already motivated, but had positive effects where motivation was low, and were found to be particularly important for children with ADHD." From this perspective, reward should not be considered a good or bad tool in itself, but rather evaluated according to its fit with the needs and signals of the child.

Beyond their effectiveness and usefulness as alternatives to corporal punishment, reviewed skills also showed important and often long-term positive effects. Examples included "improved school engagement, academic achievement, participation, communication and social relationships, better self-regulation, higher self-esteem and independence, and lower rates of depression, suicide, substance abuse, sexual risk behavior, conduct disorders, aggression and crime.". Quail and Ward concluded that the "important positive outcomes shown suggest that use of these tools should be promoted not only for prevention of violence, but for optimum child development."