https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naturalism_(philosophy)

In philosophy, naturalism is the idea that only natural laws and forces (as opposed to supernatural ones) operate in the universe. In its primary sense it is also known as ontological naturalism, metaphysical naturalism, pure naturalism, philosophical naturalism and antisupernaturalism. "Ontological" refers to ontology, the philosophical study of what exists. Philosophers often treat naturalism as equivalent to materialism.

For example, philosopher Paul Kurtz argues that nature is best accounted for by reference to material principles. These principles include mass, energy, and other physical and chemical properties accepted by the scientific community. Further, this sense of naturalism holds that spirits, deities, and ghosts are not real and that there is no "purpose" in nature. This stronger formulation of naturalism is commonly referred to as metaphysical naturalism. On the other hand, the more moderate view that naturalism should be assumed in one's working methods as the current paradigm, without any further consideration of whether naturalism is true in the robust metaphysical sense, is called methodological naturalism.

With the exception of pantheists – who believe that Nature is identical with divinity while not recognizing a distinct personal anthropomorphic god – theists challenge the idea that nature contains all of reality. According to some theists, natural laws may be viewed as secondary causes of God(s).

In the 20th century, Willard Van Orman Quine, George Santayana, and other philosophers argued that the success of naturalism in science meant that scientific methods should also be used in philosophy. According to this view, science and philosophy are not always distinct from one another, but instead form a continuum.

"Naturalism is not so much a special system as a point of view or tendency common to a number of philosophical and religious systems; not so much a well-defined set of positive and negative doctrines as an attitude or spirit pervading and influencing many doctrines. As the name implies, this tendency consists essentially in looking upon nature as the one original and fundamental source of all that exists, and in attempting to explain everything in terms of nature. Either the limits of nature are also the limits of existing reality, or at least the first cause, if its existence is found necessary, has nothing to do with the working of natural agencies. All events, therefore, find their adequate explanation within nature itself. But, as the terms nature and natural are themselves used in more than one sense, the term naturalism is also far from having one fixed meaning".

History of naturalism

Ancient and medieval philosophy

Naturalism is most notably a Western phenomenon, but an equivalent idea has long existed in the East. Naturalism was the foundation of two out of six orthodox schools and one heterodox school of Hinduism. Samkhya, one of the oldest schools of Indian philosophy puts nature (Prakriti) as the primary cause of the universe, without assuming the existence of a personal God or Ishvara. The Carvaka, Nyaya, Vaisheshika schools originated in the 7th, 6th, and 2nd century BCE, respectively. Similarly, though unnamed and never articulated into a coherent system, one tradition within Confucian philosophy embraced a form of Naturalism dating to the Wang Chong in the 1st century, if not earlier, but it arose independently and had little influence on the development of modern naturalist philosophy or on Eastern or Western culture.

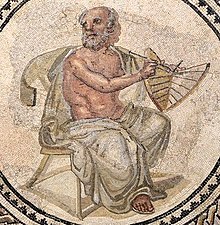

Western metaphysical naturalism originated in ancient Greek philosophy. The earliest pre-Socratic philosophers, especially the Milesians (Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes) and the atomists (Leucippus and Democritus), were labeled by their peers and successors "the physikoi" (from the Greek φυσικός or physikos, meaning "natural philosopher" borrowing on the word φύσις or physis, meaning "nature") because they investigated natural causes, often excluding any role for gods in the creation or operation of the world. This eventually led to fully developed systems such as Epicureanism, which sought to explain everything that exists as the product of atoms falling and swerving in a void.

Aristotle surveyed the thought of his predecessors and conceived of nature in a way that charted a middle course between their excesses.

Plato's world of eternal and unchanging Forms, imperfectly represented in matter by a divine Artisan, contrasts sharply with the various mechanistic Weltanschauungen, of which atomism was, by the fourth century at least, the most prominent ... This debate was to persist throughout the ancient world. Atomistic mechanism got a shot in the arm from Epicurus ... while the Stoics adopted a divine teleology ... The choice seems simple: either show how a structured, regular world could arise out of undirected processes, or inject intelligence into the system. This was how Aristotle… when still a young acolyte of Plato, saw matters. Cicero… preserves Aristotle's own cave-image: if troglodytes were brought on a sudden into the upper world, they would immediately suppose it to have been intelligently arranged. But Aristotle grew to abandon this view; although he believes in a divine being, the Prime Mover is not the efficient cause of action in the Universe, and plays no part in constructing or arranging it ... But, although he rejects the divine Artificer, Aristotle does not resort to a pure mechanism of random forces. Instead he seeks to find a middle way between the two positions, one which relies heavily on the notion of Nature, or phusis.

With the rise and dominance of Christianity in the West and the later spread of Islam, metaphysical naturalism was generally abandoned by intellectuals. Thus, there is little evidence for it in medieval philosophy.

Modern philosophy

It was not until the early modern era of philosophy and the Age of Enlightenment that naturalists like Benedict Spinoza (who put forward a theory of psychophysical parallelism), David Hume, and the proponents of French materialism (notably Denis Diderot, Julien La Mettrie, and Baron d'Holbach) started to emerge again in the 17th and 18th centuries. In this period, some metaphysical naturalists adhered to a distinct doctrine, materialism, which became the dominant category of metaphysical naturalism widely defended until the end of the 19th century.

Thomas Hobbes was a proponent of naturalism in ethics who acknowledged normative truths and properties. Immanuel Kant rejected (reductionist) materialist positions in metaphysics, but he was not hostile to naturalism. His transcendental philosophy is considered to be a form of liberal naturalism.

In late modern philosophy, Naturphilosophie, a form of natural philosophy, was developed by Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel as an attempt to comprehend nature in its totality and to outline its general theoretical structure.

A version of naturalism that arose after Hegel was Ludwig Feuerbach's anthropological materialism, which influenced Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels's historical materialism, Engels's "materialist dialectic" philosophy of nature (Dialectics of Nature), and their follower Georgi Plekhanov's dialectical materialism.

Another notable school of late modern philosophy advocating naturalism was German materialism: members included Ludwig Büchner, Jacob Moleschott, and Carl Vogt.

The current usage of the term naturalism "derives from debates in America in the first half of the 20th century. The self-proclaimed 'naturalists' from that period included John Dewey, Ernest Nagel, Sidney Hook, and Roy Wood Sellars."

Contemporary philosophy

A politicized version of naturalism that has arisen in contemporary philosophy is Ayn Rand's Objectivism. Objectivism is an expression of capitalist ethical idealism within a naturalistic framework. An example of a more progressive naturalistic philosophy is secular humanism.

The current usage of the term naturalism "derives from debates in America in the first half of the last century.

Currently, metaphysical naturalism is more widely embraced than in previous centuries, especially but not exclusively in the natural sciences and the Anglo-American, analytic philosophical communities. While the vast majority of the population of the world remains firmly committed to non-naturalistic worldviews, contemporary defenders of naturalism and/or naturalistic theses and doctrines today include Kai Nielsen, J. J. C. Smart, David Malet Armstrong, David Papineau, Paul Kurtz, Brian Leiter, Daniel Dennett, Michael Devitt, Fred Dretske, Paul and Patricia Churchland, Mario Bunge, Jonathan Schaffer, Hilary Kornblith, Leonard Olson, Quentin Smith, Paul Draper and Michael Martin, among many other academic philosophers.

According to David Papineau, contemporary naturalism is a consequence of the build-up of scientific evidence during the twentieth century for the "causal closure of the physical", the doctrine that all physical effects can be accounted for by physical causes.

By the middle of the twentieth century, the acceptance of the causal closure of the physical realm led to even stronger naturalist views. The causal closure thesis implies that any mental and biological causes must themselves be physically constituted, if they are to produce physical effects. It thus gives rise to a particularly strong form of ontological naturalism, namely the physicalist doctrine that any state that has physical effects must itself be physical. From the 1950s onwards, philosophers began to formulate arguments for ontological physicalism. Some of these arguments appealed explicitly to the causal closure of the physical realm (Feigl 1958, Oppenheim and Putnam 1958). In other cases, the reliance on causal closure lay below the surface. However, it is not hard to see that even in these latter cases the causal closure thesis played a crucial role.

In contemporary continental philosophy, Quentin Meillassoux proposed speculative materialism, a post-Kantian return to David Hume which can strengthen classical materialist ideas.

Etymology

The term "methodological naturalism" is much more recent, though. According to Ronald Numbers, it was coined in 1983 by Paul de Vries, a Wheaton College philosopher. De Vries distinguished between what he called "methodological naturalism", a disciplinary method that says nothing about God's existence, and "metaphysical naturalism", which "denies the existence of a transcendent God". The term "methodological naturalism" had been used in 1937 by Edgar S. Brightman in an article in The Philosophical Review as a contrast to "naturalism" in general, but there the idea was not really developed to its more recent distinctions.

Description

According to Steven Schafersman, naturalism is a philosophy that maintains that;

- "Nature encompasses all that exists throughout space and time;

- Nature (the universe or cosmos) consists only of natural elements, that is, of spatio-temporal physical substance – mass –energy. Non-physical or quasi-physical substance, such as information, ideas, values, logic, mathematics, intellect, and other emergent phenomena, either supervene upon the physical or can be reduced to a physical account;

- Nature operates by the laws of physics and in principle, can be explained and understood by science and philosophy;

- The supernatural does not exist, i.e., only nature is real. Naturalism is therefore a metaphysical philosophy opposed primarily by supernaturalism".

Or, as Carl Sagan succinctly put it: "The Cosmos is all that is or ever was or ever will be."

In addition Arthur C. Danto states that Naturalism, in recent usage, is a species of philosophical monism according to which whatever exists or happens is natural in the sense of being susceptible to explanation through methods which, although paradigmatically exemplified in the natural sciences, are continuous from domain to domain of objects and events. Hence, naturalism is polemically defined as repudiating the view that there exists or could exist any entities which lie, in principle, beyond the scope of scientific explanation.

Arthur Newell Strahler states: "The naturalistic view is that the particular universe we observe came into existence and has operated through all time and in all its parts without the impetus or guidance of any supernatural agency." "The great majority of contemporary philosophers urge that that reality is exhausted by nature, containing nothing 'supernatural', and that the scientific method should be used to investigate all areas of reality, including the 'human spirit'." Philosophers widely regard naturalism as a "positive" term, and "few active philosophers nowadays are happy to announce themselves as 'non-naturalists'". "Philosophers concerned with religion tend to be less enthusiastic about 'naturalism'" and that despite an "inevitable" divergence due to its popularity, if more narrowly construed, (to the chagrin of John McDowell, David Chalmers and Jennifer Hornsby, for example), those not so disqualified remain nonetheless content "to set the bar for 'naturalism' higher."

Alvin Plantinga stated that Naturalism is presumed to not be a religion. However, in one very important respect it resembles religion by performing the cognitive function of a religion. There is a set of deep human questions to which a religion typically provides an answer. In like manner naturalism gives a set of answers to these questions".

Providing assumptions required for science

According to Robert Priddy, all scientific study inescapably builds on at least some essential assumptions that cannot be tested by scientific processes; that is, that scientists must start with some assumptions as to the ultimate analysis of the facts with which it deals. These assumptions would then be justified partly by their adherence to the types of occurrence of which we are directly conscious, and partly by their success in representing the observed facts with a certain generality, devoid of ad hoc suppositions." Kuhn also claims that all science is based on assumptions about the character of the universe, rather than merely on empirical facts. These assumptions – a paradigm – comprise a collection of beliefs, values and techniques that are held by a given scientific community, which legitimize their systems and set the limitations to their investigation. For naturalists, nature is the only reality, the "correct" paradigm, and there is no such thing as supernatural, i.e. anything above, beyond, or outside of nature. The scientific method is to be used to investigate all reality, including the human spirit.

Some claim that naturalism is the implicit philosophy of working scientists, and that the following basic assumptions are needed to justify the scientific method:

- That there is an objective reality shared by all rational observers.

"The basis for rationality is acceptance of an external objective reality." "Objective reality is clearly an essential thing if we are to develop a meaningful perspective of the world. Nevertheless its very existence is assumed." "Our belief that objective reality exist is an assumption that it arises from a real world outside of ourselves. As infants we made this assumption unconsciously. People are happy to make this assumption that adds meaning to our sensations and feelings, than live with solipsism." "Without this assumption, there would be only the thoughts and images in our own mind (which would be the only existing mind) and there would be no need of science, or anything else. - That this objective reality is governed by natural laws;

"Science, at least today, assumes that the universe obeys knowable principles that don't depend on time or place, nor on subjective parameters such as what we think, know or how we behave." Hugh Gauch argues that science presupposes that "the physical world is orderly and comprehensible." - That reality can be discovered by means of systematic observation and experimentation.

Stanley Sobottka said: "The assumption of external reality is necessary for science to function and to flourish. For the most part, science is the discovering and explaining of the external world." "Science attempts to produce knowledge that is as universal and objective as possible within the realm of human understanding." - That Nature has uniformity of laws and most if not all things in nature must have at least a natural cause.

Biologist Stephen Jay Gould referred to these two closely related propositions as the constancy of nature's laws and the operation of known processes. Simpson agrees that the axiom of uniformity of law, an unprovable postulate, is necessary in order for scientists to extrapolate inductive inference into the unobservable past in order to meaningfully study it. "The assumption of spatial and temporal invariance of natural laws is by no means unique to geology since it amounts to a warrant for inductive inference which, as Bacon showed nearly four hundred years ago, is the basic mode of reasoning in empirical science. Without assuming this spatial and temporal invariance, we have no basis for extrapolating from the known to the unknown and, therefore, no way of reaching general conclusions from a finite number of observations. (Since the assumption is itself vindicated by induction, it can in no way "prove" the validity of induction — an endeavor virtually abandoned after Hume demonstrated its futility two centuries ago)." Gould also notes that natural processes such as Lyell's "uniformity of process" are an assumption: "As such, it is another a priori assumption shared by all scientists and not a statement about the empirical world." According to R. Hooykaas: "The principle of uniformity is not a law, not a rule established after comparison of facts, but a principle, preceding the observation of facts ... It is the logical principle of parsimony of causes and of economy of scientific notions. By explaining past changes by analogy with present phenomena, a limit is set to conjecture, for there is only one way in which two things are equal, but there are an infinity of ways in which they could be supposed different." - That experimental procedures will be done satisfactorily without any deliberate or unintentional mistakes that will influence the results.

- That experimenters won't be significantly biased by their presumptions.

- That random sampling is representative of the entire population.

A simple random sample (SRS) is the most basic probabilistic option used for creating a sample from a population. The benefit of SRS is that the investigator is guaranteed to choose a sample that represents the population that ensures statistically valid conclusions.

Methodological naturalism

Methodological naturalism, the second sense of the term "naturalism",(see above) is "the adoption or assumption of philosophical naturalism … with or without fully accepting or believing it.” Robert T. Pennock used the term to clarify that the scientific method confines itself to natural explanations without assuming the existence or non-existence of the supernatural. “We may therefore be agnostic about the ultimate truth of [philosophical] naturalism, but nevertheless adopt it and investigate nature as if nature is all that there is."

According to Ronald Numbers, the term "methodological naturalism" was coined in 1983 by Paul de Vries, a Wheaton College philosopher.

Both Schafersman and Strahler assert that it is illogical to try to decouple the two senses of naturalism. "While science as a process only requires methodological naturalism, the practice or adoption of methodological naturalism entails a logical and moral belief in philosophical naturalism, so they are not logically decoupled." This “[philosophical] naturalistic view is espoused by science as its fundamental assumption."

But Eugenie Scott finds it imperative to do so for the expediency of deprogramming the religious. “Scientists can defuse some of the opposition to evolution by first recognizing that the vast majority of Americans are believers, and that most Americans want to retain their faith.” Scott apparently believes that “individuals can retain religious beliefs and still accept evolution through methodological naturalism. Scientists should therefore avoid mentioning metaphysical naturalism and use methodological naturalism instead.” “Even someone who may disagree with my logic … often understands the strategic reasons for separating methodological from philosophical naturalism—if we want more Americans to understand evolution.”

Scott’s approach has found success as illustrated in Ecklund’s study where some religious scientists reported that their religious beliefs affect the way they think about the implications – often moral – of their work, but not the way they practice science within methodological naturalism. Papineau notes that "Philosophers concerned with religion tend to be less enthusiastic about metaphysical naturalism and that those not so disqualified remain content "to set the bar for 'naturalism' higher."

In contrast to Schafersman, Strahler, and Scott, Robert T. Pennock, an expert witness at the Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District trial and cited by the Judge in his Memorandum Opinion. described "methodological naturalism" stating that it is not based on dogmatic metaphysical naturalism.

Pennock further states that as supernatural agents and powers "are above and beyond the natural world and its agents and powers" and "are not constrained by natural laws", only logical impossibilities constrain what a supernatural agent cannot do. In addition he says: "If we could apply natural knowledge to understand supernatural powers, then, by definition, they would not be supernatural." "Because the supernatural is necessarily a mystery to us, it can provide no grounds on which one can judge scientific models." "Experimentation requires observation and control of the variables.... But by definition we have no control over supernatural entities or forces."

The position that the study of the function of nature is also the study of the origin of nature is in contrast with opponents who take the position that functioning of the cosmos is unrelated to how it originated. While they are open to supernatural fiat in its invention and coming into existence, during scientific study to explain the functioning of the cosmos, they do not appeal to the supernatural. They agree that allowing “science to appeal to untestable supernatural powers to explain how nature functions would make the scientist's task meaningless, undermine the discipline that allows science to make progress, and would be as profoundly unsatisfying as the ancient Greek playwright's reliance upon the deus ex machina to extract his hero from a difficult predicament."

Views on methodological naturalism

W. V. O. Quine

W. V. O. Quine describes naturalism as the position that there is no higher tribunal for truth than natural science itself. In his view, there is no better method than the scientific method for judging the claims of science, and there is neither any need nor any place for a "first philosophy", such as (abstract) metaphysics or epistemology, that could stand behind and justify science or the scientific method.

Therefore, philosophy should feel free to make use of the findings of scientists in its own pursuit, while also feeling free to offer criticism when those claims are ungrounded, confused, or inconsistent. In Quine's view, philosophy is "continuous with" science, and both are empirical. Naturalism is not a dogmatic belief that the modern view of science is entirely correct. Instead, it simply holds that science is the best way to explore the processes of the universe and that those processes are what modern science is striving to understand.

Karl Popper

Karl Popper equated naturalism with inductive theory of science. He rejected it based on his general critique of induction (see problem of induction), yet acknowledged its utility as means for inventing conjectures.

A naturalistic methodology (sometimes called an "inductive theory of science") has its value, no doubt. ... I reject the naturalistic view: It is uncritical. Its upholders fail to notice that whenever they believe to have discovered a fact, they have only proposed a convention. Hence the convention is liable to turn into a dogma. This criticism of the naturalistic view applies not only to its criterion of meaning, but also to its idea of science, and consequently to its idea of empirical method.

— Karl R. Popper, The Logic of Scientific Discovery, (Routledge, 2002), pp. 52–53, ISBN 0-415-27844-9.

Popper instead proposed that science should adopt a methodology based on falsifiability for demarcation, because no number of experiments can ever prove a theory, but a single experiment can contradict one. Popper holds that scientific theories are characterized by falsifiability.

Alvin Plantinga

Alvin Plantinga, Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at Notre Dame, and a Christian, has become a well-known critic of naturalism. He suggests, in his evolutionary argument against naturalism, that the probability that evolution has produced humans with reliable true beliefs, is low or inscrutable, unless the evolution of humans was guided (for example, by God). According to David Kahan of the University of Glasgow, in order to understand how beliefs are warranted, a justification must be found in the context of supernatural theism, as in Plantinga's epistemology. (See also supernormal stimuli).

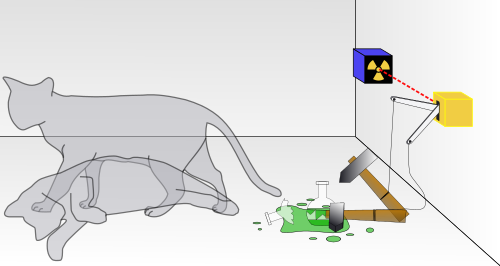

Plantinga argues that together, naturalism and evolution provide an insurmountable "defeater for the belief that our cognitive faculties are reliable", i.e., a skeptical argument along the lines of Descartes' evil demon or brain in a vat.

Take philosophical naturalism to be the belief that there aren't any supernatural entities – no such person as God, for example, but also no other supernatural entities, and nothing at all like God. My claim was that naturalism and contemporary evolutionary theory are at serious odds with one another – and this despite the fact that the latter is ordinarily thought to be one of the main pillars supporting the edifice of the former. (Of course I am not attacking the theory of evolution, or anything in that neighborhood; I am instead attacking the conjunction of naturalism with the view that human beings have evolved in that way. I see no similar problems with the conjunction of theism and the idea that human beings have evolved in the way contemporary evolutionary science suggests.) More particularly, I argued that the conjunction of naturalism with the belief that we human beings have evolved in conformity with current evolutionary doctrine ... is in a certain interesting way self-defeating or self-referentially incoherent.

— Alvin Plantinga, Naturalism Defeated?: Essays on Plantinga's Evolutionary Argument Against Naturalism, "Introduction"

The argument is controversial and has been criticized as seriously flawed, for example, by Elliott Sober.

Robert T. Pennock

Robert T. Pennock states that as supernatural agents and powers "are above and beyond the natural world and its agents and powers" and "are not constrained by natural laws", only logical impossibilities constrain what a supernatural agent cannot do. He says: "If we could apply natural knowledge to understand supernatural powers, then, by definition, they would not be supernatural." As the supernatural is necessarily a mystery to us, it can provide no grounds on which one can judge scientific models. "Experimentation requires observation and control of the variables.... But by definition we have no control over supernatural entities or forces." Science does not deal with meanings; the closed system of scientific reasoning cannot be used to define itself. Allowing science to appeal to untestable supernatural powers would make the scientist's task meaningless, undermine the discipline that allows science to make progress, and "would be as profoundly unsatisfying as the ancient Greek playwright's reliance upon the deus ex machina to extract his hero from a difficult predicament."

Naturalism of this sort says nothing about the existence or nonexistence of the supernatural, which by this definition is beyond natural testing. As a practical consideration, the rejection of supernatural explanations would merely be pragmatic, thus it would nonetheless be possible for an ontological supernaturalist to espouse and practice methodological naturalism. For example, scientists may believe in God while practicing methodological naturalism in their scientific work. This position does not preclude knowledge that is somehow connected to the supernatural. Generally however, anything that one can examine and explain scientifically would not be supernatural, simply by definition.

Criticism

Colin Murray Turbayne

The Australian philosopher Colin Murray Turbayne puts forth an objection to naturalism which is based upon linguistic grounds. His objections refer to several of the concepts which form the a priori foundation for naturalism in general. In particular, Turbayne calls attention to the concepts of "substance" and "substratum" which in his view convey little if any meaning at best. He asserts that along with several "physicalist" constructs, these concepts have been mistakenly incorporated through the use of deductive reasoning into the hypotheses underlying materialism in the modern world. In addition, he argues further that they are more properly characterized as being purely metaphorical in nature rather than literal descriptions of an independent objective truth. Specifically, he identifies the "mechanistic" metaphors utilized by Isaac Newton and the mind-body dualism which was embraced by René Descartes as being particularly problematic. Turbayne argues that over time humanity has become victimized by mistaking such metaphorical constructs for literal truths, which now form the basis for considerable obfuscation and confusion within the realms of metaphysics and epistemology. He concludes by observing that humanity can readily adopt more useful models of the natural world only after first acknowledging the manner in which such purely metaphorical constructs have taken on the guise of literal truth within much of the modern world.