In some countries, early in-person voting or postal voting (or both) are available to all voters. In other countries, only some voters (such as those who are expected to be out of the country or hospitalized on election day are eligible) are eligible to cast ballots via these methods.

Australia and New Zealand

Australia

In Australia, where voting is compulsory, early voting is usually known as "pre-poll voting". Voters are able to cast a pre-poll vote for a number of reasons, including being away from the electorate, travelling, impending maternity, being unable to leave one's workplace, having religious beliefs that prevent attendance at a polling place, or being more than 8 km from a polling place. There were over 600 early voting centres available in 2016.

At the 2019 Australian federal election, 6.1 million votes were cast early (including postal votes), equating to 40.7 percent of total votes cast. This represented an increase from 26.4 percent at the 2013 election and 13.7 percent at the 2007 election. Following the 2019 elections, members of the parliamentary standing committee on electoral matters expressed concern about the length of the pre-poll voting period, suggesting that it was imposing costs on both the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) and political parties, and that electors voting too early may be unable to respond to developments in the final weeks of the election campaign.

New Zealand

Early voting, or advance voting, has been possible in New Zealand without a reason since 2008. Advance voting opens 12 days before the election day, with around 500 polling booths set up across the country. Voters attending an appropriate advance polling booth for their electorate (constituency) can cast an ordinary vote in the same way they would if voting on election day. If the voter is outside the electorate, enrolled after the cutoff date (31 days before election day), or is on the unpublished roll, they must cast a special vote.

In the 2011 election, 334,600 advance votes were cast, representing 14.7% of all votes cast. This grew to 48% in the 2017 election and to 66.7% in the 2020 election

Europe

A 2020 report by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA) surveyed the use of voting arrangements in Europe, reporting on the prevalence of in-country postal voting, early voting, mobile voting, and proxy voting in various European countries.

The IDEA report defined early voting, for purposes of the IDEA dataset was defined as "in-person opportunities for submitting one's vote at a polling station before election day," excluding "other early methods that are not in-person (such as postal or e-voting) or that do not take place in a polling station (such as mobile voting)." Applying this definition, Switzerland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Estonia, and Latvia offer early voting to all voters. Iceland, Portugal, Slovenia, Lithuania, Belarus, and Russia offer early voting to some voters.

The IDEA report defined in-country postal voting, for purposes of its dataset, as "those measures that allow a voter to submit their ballot by physical post to the election administration" and noted that "While postal voting is in principle early voting, it differs in that the vote can be physically submitted remotely by the voter themselves." Iceland, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Germany, Poland, Liechtenstein, and Luxembourg offer in-country postal voting to all voters. The Republic of Ireland, Spain, the Netherlands, Austria, Slovenia, and Lithuania offer in-country postal voting to some voters.

Finland

In Finland, eligible voters may cast ballots either on election day or by advance voting. Advancing voting begins on a Wednesday, eleven days before election day. The advance-voting period ends eight days before election day (for votes cast abroad at designated Finnish embassies) and five days before election day (for votes cast within Finland). Any qualified voter may cast a ballot at a "general advance polling station" (a Finland municipal office or certain post offices and Finnish embassies abroad). "Special advance polling stations" are set up at hospitals for patients and prisons for detainees. Additionally, Finnish voters who are unable to travel to advance polling stations due to mobility impairments or illness may cast advance ballots at home (election commissioners make house calls to receive votes from such person). Crews of traveling Finnish ships may also cast ballots via advance voting, beginning 18 days before election day.

Germany

Germany does not have in-person early voting, but allows all eligible voters to vote by mail. Voting by mail was adopted in West Germany beginning in 1957, but was originally a method mostly used for those with a particular reason preventing them from casting an in-person ballot. The proportion of German voters casting postal ballots has steadily increased since the 1990 reunification of Germany, and the excuse requirement was eliminated in 2008. In the 2005 German federal election, 19% of all voters voted early. In the 2017 German federal election, a then-record 28.6% of voters cast ballots by mail. In the 2021 German federal election, 47.3% of voters cast ballots by mail, setting a new record.

Ireland

In the Republic of Ireland, it is traditional for voters on the remote coastal islands to vote on the day prior to the official date of the election. This aims to avoid the possibility that bad weather might impede the delivery of ballot boxes to the count center on the mainland. However, the practice is not universally popular.

Norway

In Norway early voting is known as "forhåndsstemming". By law, election day is set to a Monday in September in the year of the end of the current term. Early voting is usually opened 1 month before election day, and closes the Friday before. Up to and including the Friday, everyone can vote anywhere in the country. On election day, voting has to occur within the municipality the voter is a resident of by the end of June.

At the general election of 2009, 707,489 Norwegians voted in advance, 200 000 more than the previous record, in 2001.

The share that do early voting has steadily increased and in the national elections in 2021, 57.9% of votes cast were early votes. With 1.7 million early voters.

Sweden

Sweden has traditionally had a high participation in elections and tries to make it as easy as possible to vote. No registration is needed, since everyone is generally registered with a home address. Normally, a voter should vote on the election day in the specified polling station, but everyone can vote during the last week at an early polling station, anywhere in the country, usually municipality-owned places like libraries.

Also, on election day, some polling places are open, even though the election day is always on Sunday. In hospitals and homes for the elderly, there are special voting opportunities. In elections until 1998, post offices were used for several decades as early voting stations (post offices now belong to a commercial company and are no longer nationally administered). Swedes living abroad must register their address and can vote at embassies or through mail.

The early votes are transported to the voter's polling station in double envelopes. On election day, a voter can vote at the polling station. Before the early vote is counted, officials check if the voter has voted at the polling station. If that is the case, the early vote is destroyed, with the inner envelope unopened. Early votes that do not reach the polling station in time are transported to the County Administrative Board and counted if the voter has not already voted.

Switzerland

Swiss federal law allows postal voting in all federal elections and referendums, and all cantons allow it for cantonal ballot issues. All voters receive their personal ballot by mail a few weeks before the election or referendum. They may cast it at a polling station on election day or mail it back at any prior time.

Asia and elsewhere

Russia

In Russia, early voting, according to the decision of the election commission, can be organized in special poll stations formed in remote and hard-to-reach areas, on ships that will be sailing on election day and at polar stations. At the same time, early voting can be held no earlier than twenty days before the election day.

In 2020, against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, a law was passed allowing early voting at all polling stations. For the first time, this system was used in the referendum on amendments to the constitution, which was held on 1 July 2020, but citizens had the opportunity to vote within a week before the main day. This was done for sanitary purposes, to reduce the number of people present at the same time at the polling stations. Later, the period of early voting was reduced to two days before the election day. Such a three-day voting was used for regional elections in September 2020. However, such a decision is not mandatory and can be made by the election commission within ten days after the election is scheduled. If the election Commission has not made such a decision, voting takes place only within one day.

Thailand

In Thailand, early voting is known as เลือกตั้งล่วงหน้า (advance voting). The Election Commission administers advancing voting. Early voting in the 2011 Thai general election was arranged on a Sunday (June 26, 2011) while prior elections were arranged on both Saturday and Sunday. Around 2.6 million people, including 1.07 million in Bangkok turned up to vote, however, many potential voters were unable to vote because of large crowds.

North America

Canada

In Canada, elections are administered by Elections Canada. Early in-person voting is called advance polls, which are held on the 10th, 9th, 8th and 7th days before election day at designated advance-poll stations. Canadian voters may locate the date, hours, and address of their advance-poll station at the Elections Canada website, on their voter information card, or by telephoning Elections Canada. About 4.9 million Canadians cast advance votes in the 2019 election, and almost 5.8 million Canadians cast ballots during the four advance-poll dates of the 2021 election, setting a record.

Canadians may also vote, upon application, at Elections Canada local offices (established during election seasons in every riding in Canada), or by mail. Ballots cast via these methods are termed "special ballots." Historically, voting by mail has been fairly rare in Canada; of the 18.4 million total votes in the 2019 Canadian election, slightly under 50,000 voters cast ballots by mail, with most of these ballots coming from Canadians living abroad. Voting by mail in Canada increased during the 2021 election, with more than 1.1 million special ballots received (including from Canadian Forces servicemembers, Canadians living abroad, Canadians away from home on election day, and incarcerated Canadians); of this total, about 99,988 special ballots were not counted because they arrived after the receipt deadline (6 p.m. on election day), did not have a voter signature, or had some other problem.

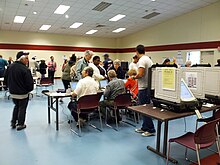

United States

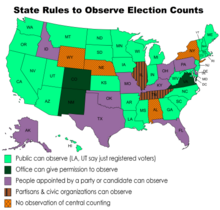

As of 2022, 46 states, the District of Columbia, American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands offer in-person voting before Election Day. Of the 46 states that allow early in-person voting seven states have all-mail voting. In these states, each eligible, registered voter is sent a ballot, which can either be returned by mail, or dropped off at designated site during the early voting period.

The duration, start date, and end date of the early in-person voting period varies from state to state, from a low of 3 days to a high of 46 days; the average number of days of early in-person voting is 23. Some states give discretion to local election officials (sometimes county clerks) to add certain days of early voting.

Of states that permit early in-person voting (excluding the seven states that have "all-mail" elections), 23 states and D.C. allow some weekend early voting (on Saturdays, Sundays, or both).

The National Conference of State Legislatures provides up-to-date information on each state's laws with links to relevant election statutes.

As of 2022, only four states do not currently offer in-person early voting: Alabama, Connecticut, Mississippi, and New Hampshire. However, in 2022, Connecticut voters approved a state constitutional amendment authorizing in-person early voting in Connecticut for future elections.

In addition to (or in lieu of) in-person early voting, all states offer absentee ballots to some voters, with significant differences among states. As of 2022, 35 states and D.C. offer "no-excuse absentee voting" in which any qualified voter may cast an absentee ballot without an excuse; in the remaining states, an absentee ballot will only be provided to a voter with a valid excuse. Absentee ballots (also called mail-in ballots) are often returned to election offices by mail (see postal voting in the United States) but some states offer "in-person absentee voting" (in which the voter requests, completes, signs, and submits the absentee ballot at a polling place). The voting experience for in-person absentee balloting is similar to the early-voting experience.

States adopted early voting at different times. For example, Florida officially began early voting in 2004, and voters in Maryland approved a constitutional amendment in November 2008 to allow early voting, starting with the primary elections in 2010. Early voting was first used in Massachusetts for the general election of November 2016.w York began early voting in 2019, as a result of a state law requiring eight days of early voting throughout the state.

The COVID-19 pandemic in the United States led many states both to reduce the number of polling stations for the 2020 United States elections and to relax requirements for both mail-in and early voting, including mailing applications to all active registered voters and providing drop-boxes for ballots. In the November 2020 elections, about 26% of votes nationwide were cast by early in-person voting, as compared to 46% of votes cast by mail/absentee ballot and 28% of votes cast in Election Day in-person voting.

After the attempts to overturn the 2020 United States presidential election, following false claims of widespread voter fraud in the election by Donald Trump, Republican lawmakers initiated a push to restrict early voting (see Republican efforts to restrict voting following the 2020 presidential election).

In 2020, MTV founded the campaign for "Vote Early Day" as a civic holiday to celebrate the concept of early voting, directed primarily at young people. The MTV program partnered with businesses and nonprofits, and its advantage being that it isn’t ‘owned’ by any one entity.