| Cascades Volcanoes | |

|---|---|

Mount Rainier from the northeast | |

| Geography | |

| Location | California, Oregon, and Washington, United States, and British Columbia, Canada |

The Cascade Volcanoes (also known as the Cascade Volcanic Arc or the Cascade Arc) are a number of volcanoes in a volcanic arc in western North America, extending from southwestern British Columbia through Washington and Oregon to Northern California, a distance of well over 700 miles (1,100 km). The arc formed due to subduction along the Cascadia subduction zone. Although taking its name from the Cascade Range, this term is a geologic grouping rather than a geographic one, and the Cascade Volcanoes extend north into the Coast Mountains, past the Fraser River which is the northward limit of the Cascade Range proper.

Some of the major cities along the length of the arc include Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver, and the population in the region exceeds 10 million. All could be potentially affected by volcanic activity and great subduction-zone earthquakes along the arc. Because the population of the Pacific Northwest is rapidly increasing, the Cascade volcanoes are some of the most dangerous, due to their eruptive history and potential for future eruptions, and because they are underlain by weak, hydrothermally altered volcanic rocks that are susceptible to failure. Consequently, Mount Rainier is one of the Decade Volcanoes identified by the International Association of Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth's Interior (IAVCEI) as being worthy of particular study, due to the danger it poses to Seattle and Tacoma. Many large, long-runout landslides originating on Cascade volcanoes have engulfed valleys tens of kilometers from their sources, and some of the areas affected now support large populations.

The Cascade Volcanoes are part of the Pacific Ring of Fire, the ring of volcanoes and associated mountains around the Pacific Ocean. The Cascade Volcanoes have erupted several times in recorded history. Two most recent were Lassen Peak in 1914 to 1921 and a major eruption of Mount St. Helens in 1980. It is also the site of Canada's most recent major eruption about 2,350 years ago at the Mount Meager massif.

Geology

The Cascade Arc includes nearly 20 major volcanoes, among a total of over 4,000 separate volcanic vents including numerous stratovolcanoes, shield volcanoes, lava domes, and cinder cones, along with a few isolated examples of rarer volcanic forms such as tuyas. Volcanism in the arc began about 37 million years ago; however, most of the present-day Cascade volcanoes are less than 2,000,000 years old, and the highest peaks are less than 100,000 years old. Twelve volcanoes in the arc are over 10,000 feet (3,000 m) in elevation, and the two highest, Mount Rainier and Mount Shasta, exceed 14,000 feet (4,300 m). By volume, the two largest Cascade volcanoes are the broad shields of Medicine Lake Volcano and Newberry Volcano, which are about 145 and 108 cubic miles (600 and 450 km3) respectively. Glacier Peak is the only Cascade volcano that is made exclusively of dacite. The history of the cascade volcanoes can be separated into three major chapters which are discussed below.

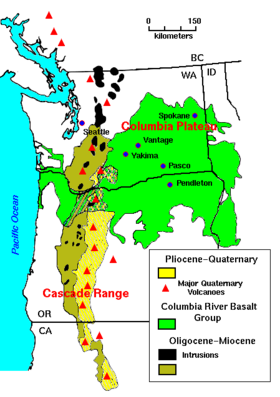

West Cascades period

The time between 37 million and 17 million years ago is known as the West Cascades period, this era is characterized as being when the volcanoes in this region were exceptionally active. During this time the arc was situated a little farther west than it is today. One volcano that was active during this time was the Mount Aix Volcanic Complex, which erupted more than 100 km3 (24 cu mi) of tephra and pyroclastic debris over the span of just three eruptions. Lavas representing the earliest stage in the development of the Cascade Volcanic Arc mostly crop out south of the North Cascades proper, where uplift of the Cascade Range has been less, and a thicker blanket of Cascade Arc volcanic rocks has been preserved. In the North Cascades, geologists have not yet identified with any certainty any volcanic rocks as old as 35 million years, but remnants of the ancient arc's internal plumbing system persist in the form of plutons, which are the crystallized magma chambers that once fed the early Cascade volcanoes. The greatest mass of exposed Cascade Arc plumbing is the Chilliwack batholith, which makes up much of the northern part of North Cascades National Park and adjacent parts of British Columbia beyond. Individual plutons range in age from about 35 million years old to 2.5 million years old. The older rocks invaded by all this magma were affected by the heat. Around the plutons of the batholith, the older rocks recrystallized. This contact metamorphism produced a fine mesh of interlocking crystals in the old rocks, generally strengthening them and making them more resistant to erosion. Where the recrystallization was intense, the rocks took on a new appearance dark, dense and hard. Many rugged peaks in the North Cascades owe their prominence to this baking. The rocks holding up many such North Cascade giants, as Mount Shuksan, Mount Redoubt, Mount Challenger, and Mount Hozomeen, are all partly recrystallized by plutons of the nearby and underlying Chilliwack batholith.

Widespread dormancy period

The West Cascades period came to an end 17 million years ago when the Columbia River flood basalts began erupting in eastern Washington and Oregon. For a reason unknown to scientists the initiation of the flood basalts seemingly caused a significant dip in volcanic activity in the cascade chain lasting for over 8 million years. During this time the volcanoes were stripped down to their cores by weathering and erosion because they were not active enough to rebuild. This low point lasted from 17 to 9 million years ago and came to end when the Columbia flood basalts waned.

High Cascades period

As production of the Columbia River flood basalts slowed 9 million years ago the Cascade volcanoes became active again. The volcanic arc also drifted farther east to its present location. When the Columbia basalts stopped entirely 6 million years ago the Cascades of central Oregon spectacularly flared up. This flare up lasted between 6.25 and 5.45 million years ago and is known as the Deschutes Formation. During this 800,000 year span approximately 400 km3 to 675 km3 of pyroclastic material was expelled in 78 distinct eruptions. It has been hypothesized that a heightened flux of basalt, possibly induced by tectonic slab-rollback, was focused beneath the volcanic arc and into the shallow crust by minor amounts of crustal extension. This extension allowed for the high flux of basalt to be stored at shallow levels beneath a new arc locus within fertile crust, resulting in the silica-rich volcanism we see in the Deschutes Formation. After this pulse of activity the cascades retreated to the levels of activity we are more familiar with today.

For the remaining 5 or so million years the ancestors of many of the modern day Cascade volcanoes were built. Around half a million years ago a generation of older volcanoes died and many of the stratovolcanoes that we see today began their growth such as Glacier Peak and Mt. Shasta (600,000 years ago), Mt. Rainier and Mt. Hood (500,000 years ago), Mt. Adams (450,000 years ago), and Mt. Mazama (420,000 years ago).

Modern arc

The volcanoes of the Cascade Arc share some general characteristics, but each has its own unique geological traits and history. Lassen Peak in California, which last erupted in 1917, is the southernmost historically active volcano in the arc, while the Mount Meager massif in British Columbia, which erupted about 2,350 years ago, is generally considered the northernmost member of the arc. A few isolated volcanic centers northwest of the Mount Meager massif such as the Silverthrone Caldera, which is a circular 20 km (12 mi) wide, deeply dissected caldera complex, may also be the product of Cascadia subduction because the igneous rocks andesite, basaltic andesite, dacite and rhyolite can also be found at these volcanoes as they are elsewhere along the subduction zone. At issue are the current estimates of plate configuration and rate of subduction, but based on the chemistry of these volcanoes, they are also subduction related and therefore part of the Cascade Volcanic Arc. The Cascade Volcanic Arc appears to be segmented; the central portion of the arc is the most active and the northern end least active.

The Garibaldi Volcanic Belt is the northern extension of the Cascade Arc. Volcanoes within the volcanic belt are mostly stratovolcanoes along with the rest of the arc, but also include calderas, cinder cones, and small isolated lava masses. The eruption styles within the belt range from effusive to explosive, with compositions from basalt to rhyolite. Due to repeated continental and alpine glaciations, many of the volcanic deposits in the belt reflect complex interactions between magma composition, topography, and changing ice configurations. Four volcanoes within the belt appear related to seismic activity since 1975, including: Mount Meager massif, Mount Garibaldi and Mount Cayley.

The Pemberton Volcanic Belt is an eroded volcanic belt north of the Garibaldi Volcanic Belt, which appears to have formed during the Miocene before fracturing of the northern end of the Juan de Fuca Plate. The Silverthrone Caldera is the only volcano within the belt that appears related to seismic activity since 1975.

The Mount Meager massif is the most unstable volcanic massif in Canada. It has dumped clay and rock several meters deep into the Pemberton Valley at least three times during the past 7,300 years. Recent drilling into the Pemberton Valley bed encountered remnants of a debris flow that had traveled 50 km (31 mi) from the volcano shortly before it last erupted 2,350 years ago. About 1,000,000,000 cubic metres (0.24 cu mi) of rock and sand extended over the width of the valley. Two previous debris flows, about 4,450 and 7,300 years ago, sent debris at least 32 km (20 mi) from the volcano. Recently, the volcano has created smaller landslides about every ten years, including one in 1975 that killed four geologists near Meager Creek. The possibility of the Mount Meager massif covering stable sections of the Pemberton Valley in a debris flow is estimated at one in 2,400 years. There is no sign of volcanic activity with these events. However, scientists warn the volcano could release another massive debris flow over populated areas any time without warning.

In the past, Mount Rainier has had large debris avalanches, and has also produced enormous lahars due to the large amount of glacial ice present. Its lahars have reached all the way to Puget Sound. Around 5,000 years ago, a large chunk of the volcano slid away and that debris avalanche helped to produce the massive Osceola Mudflow, which went all the way to the site of present-day Tacoma and south Seattle. This massive avalanche of rock and ice took out the top 1,600 feet (490 m) of Rainier, bringing its height down to around 14,100 feet (4,300 m). About 530 to 550 years ago, the Electron Mudflow occurred, although this was not as large-scale as the Osceola Mudflow.

While the Cascade volcanic arc (a geological term) includes volcanoes such as the Mount Meager massif and Mount Garibaldi, which lie north of the Fraser River, the Cascade Range (a geographic term) is considered to have its northern boundary at the Fraser.

Largest eruptions

Human history

Native Americans have inhabited the area for thousands of years and developed their own myths and legends concerning the Cascade volcanoes. According to some of these tales, Mounts Baker, Jefferson, Shasta and Garibaldi were used as refuge from a great flood. Other stories, such as the Bridge of the Gods tale, had various High Cascades such as Hood and Adams, act as god-like chiefs who made war by throwing fire and stone at each other. St. Helens with its pre-1980 graceful appearance, was regaled as a beautiful maiden for whom Hood and Adams feuded. Among the many stories concerning Mount Baker, one tells that the volcano was formerly married to Mount Rainier and lived in that vicinity. Then, because of a marital dispute, she picked herself up and marched north to her present position. Native tribes also developed their own names for the High Cascades and many of the smaller peaks, the most well known to non-natives being Tahoma, the Lushootseed name for Mount Rainier. Mount Cayley and The Black Tusk are known to the Squamish people who live nearby as "the Landing Place of the Thunderbird".

Hot springs in the Canadian side of the arc, were originally used and revered by First Nations people. The springs located on Meager Creek are called Teiq in the language of the Lillooet people and were the farthest up the Lillooet River. The spirit-beings/wizards known as "the Transformers" reached them during their journey into the Lillooet Country, and were a "training" place for young First Nations men to acquire power and knowledge. In this area, also, was found the blackstone chief's head pipe that is famous of Lillooet artifacts; found buried in volcanic ash, one supposes from the 2350 BP eruption of the Mount Meager massif.

Legends associated with the great volcanoes are many, as well as with other peaks and geographical features of the arc, including its many hot springs and waterfalls and rock towers and other formations. Stories of Tahoma – today Mount Rainier and the namesake of Tacoma, Washington – allude to great, hidden grottos with sleeping giants, apparitions and other marvels in the volcanoes of Washington, and Mount Shasta in California has long been well known for its associations with everything from Lemurians to aliens to elves and, as everywhere in the arc, Sasquatch or Bigfoot.

In the spring of 1792 British navigator George Vancouver entered Puget Sound and started to give English names to the high mountains he saw. Mount Baker was named for Vancouver's third lieutenant, the graceful Mount St. Helens for a famous diplomat, Mount Hood was named in honor of Samuel Hood, 1st Viscount Hood (an admiral of the Royal Navy) and the tallest Cascade, Mount Rainier, is the namesake of Admiral Peter Rainier. Vancouver's expedition did not, however, name the arc these peaks belonged to. As marine trade in the Strait of Georgia and Puget Sound proceeded in the 1790s and beyond, the summits of Rainier and Baker became familiar to captains and crews (mostly British and American).

With the exception of the 1915 eruption of remote Lassen Peak in Northern California, the arc was quiet for more than a century. Then, on May 18, 1980, the dramatic eruption of little-known Mount St. Helens shattered the quiet and brought the world's attention to the arc. Geologists were also concerned that the St. Helens eruption was a sign that long-dormant Cascade volcanoes might become active once more, as in the period from 1800 to 1857 when a total of eight erupted. None have erupted since St. Helens, but precautions are being taken nevertheless, such as the Mount Rainier Volcano Lahar Warning System in Pierce County, Washington.

Cascadia subduction zone

The Cascade Volcanoes were formed by the subduction of the Juan de Fuca, Explorer and the Gorda Plate (remnants of the much larger Farallon Plate) under the North American Plate along the Cascadia subduction zone. This is a 680-mile (1,090 km) long fault, running 50 miles (80 km) off the coast of the Pacific Northwest from northern California to Vancouver Island, British Columbia. The plates move at a relative rate of over 0.4 inches (10 mm) per year at a somewhat oblique angle to the subduction zone.

Because of the very large fault area, the Cascadia subduction zone can produce very large earthquakes, magnitude 9.0 or greater, if rupture occurred over its whole area. When the "locked" zone stores up energy for an earthquake, the "transition" zone, although somewhat plastic, can rupture. Thermal and deformation studies indicate that the locked zone is fully locked for 60 km (37 mi) downdip from the deformation front. Farther downdip, there is a transition from fully locked to aseismic sliding.

Unlike most subduction zones worldwide, there is no oceanic trench present along the continental margin in Cascadia. Instead, terranes and the accretionary wedge have been uplifted to form a series of coast ranges and exotic mountains. A high rate of sedimentation from the outflow of the three major rivers (Fraser River, Columbia River, and Klamath River) which cross the Cascade Range contributes to further obscuring the presence of a trench. However, in common with most other subduction zones, the outer margin is slowly being compressed, similar to a giant spring. When the stored energy is suddenly released by slippage across the fault at irregular intervals, the Cascadia subduction zone can create very large earthquakes such as the Mw 8.7–9.2 Cascadia earthquake of 1700.

Famous eruptions

1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens

The 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens was one of the most closely studied volcanic eruptions in the arc and one of the best studied ever. It was a plinian style eruption with a VEI 5 and was the most significant to occur in the lower 48 U.S. states in recorded history. An earthquake at 8:32 a.m. on May 18, 1980, caused the entire weakened north face to slide away. An ash column rose 15 miles into the atmosphere and deposited ash in 11 U.S. states. The eruption killed 57 people and thousands of animals and caused more than a billion U.S. dollars in damage. Over 1.3 km3 of tephra was ejected during this eruption.

1914–1917 eruptions of Lassen Peak

On May 22, 1915, an explosive eruption at Lassen Peak devastated nearby areas and rained volcanic ash as far away as 200 miles (320 km) to the east. A huge column of volcanic ash and gas rose more than 30,000 feet (9,100 m) into the air and was visible from as far away as Eureka, California, 150 miles (240 km) to the west. A pyroclastic flow swept down the side of the volcano, devastating a 3-square-mile (7.8 km2) area. This explosion was the most powerful in a 1914–1917 series of eruptions at Lassen Peak.

2350 BP (400 BC) eruption of the Mount Meager massif

The Mount Meager massif produced the most recent major eruption in Canada, sending ash as far away as Alberta. The eruption sent an ash column approximately 20 km (12 mi) high into the stratosphere. This activity produced a diverse sequence of volcanic deposits, well exposed in the bluffs along the Lillooet River, which is defined as the Pebble Creek Formation. The eruption was episodic, occurring from a vent on the north-east side of Plinth Peak. An unusual, thick apron of welded vitrophyric breccia may represent the explosive collapse of an early lava dome, depositing ash several meters (a dozen or so feet) in thickness near the vent area. The volume of magma erupted in this event is equal to 2 km3.

7700 BP (5783 BC) eruption of Mount Mazama

The 7,700 BP eruption of Mount Mazama was a large catastrophic eruption in the U.S. state of Oregon. It began with a large eruption column with pumice and ash that erupted from a single vent. The eruption was so great that most of Mount Mazama collapsed to form a caldera and subsequent smaller eruptions occurred as water began to fill in the caldera to form Crater Lake. Volcanic ash from the eruption was carried across most of the Pacific Northwest as well as parts of western Canada.

13100 BP (11,150 BC) eruptions of Glacier Peak

About 13,000 years ago, Glacier Peak generated an unusually strong sequence of eruptions depositing volcanic ash as far away as Wyoming. These eruptions were some of the largest to occur in Washington state in the last 15,000 years, with one of them being a staggering 5 times larger than the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens.

| Unit Name | DRE Volume | Bulk Deposit Volume | Plume Height |

|---|---|---|---|

| Layer B | 2.1 km3 (0.50 cu mi) | 6.5 km3 (1.6 cu mi) | 31 km (19 mi) |

| Layer M | 0.4 km3 (0.096 cu mi) | 1.1 km3 (0.26 cu mi) | N/A |

| Layer G | 1.9 km3 (0.46 cu mi) | 6.0 km3 (1.4 cu mi) | 32 km (20 mi) |

Other eruptions

Silverthrone Caldera

Most of the Silverthrone Caldera's eruptions in the Pacific Range occurred during the Last Glacial Period and was episodically active during both Pemberton and Garibaldi Volcanic Belt stages of volcanism. The caldera is one of the largest of the few calderas in western Canada, measuring about 30 kilometres (19 mi) long (north-south) and 20 kilometres (12 mi) wide (east-west). The last eruption from Mount Silverthrone ran up against ice in Chernaud Creek. The lava was dammed by the ice and made a cliff with a waterfall up against it. The most recent activity was 1000 years ago.

Mount Garibaldi

Mount Garibaldi in the Pacific Range was last active about 10,700 to 9,300 years ago from a cinder cone called Opal Cone. It produced a 15 km (9.3 mi) long broad dacite lava flow with prominent wrinkled ridges. The lava flow is unusually long for a silicic lava flow.

Mount Baker

During the mid-19th century, Mount Baker erupted for the first time in several thousand years. Fumarole activity remains in Sherman Crater, just south of the volcano's summit, became more intense in 1975 and is still energetic. However, an eruption is not expected in the near future.

Glacier Peak

Glacier Peak last erupted about 200–300 years ago and has erupted about six times in the past 4,000 years.

Mount Rainier

Mount Rainier last erupted between 1824 and 1854, but many eyewitnesses reported eruptive activity in 1858, 1870, 1879, 1882, and in 1894 as well. Mount Rainier has created at least four eruptions and many lahars in the past 4,000 years.

Mount Adams

Mount Adams was last active about 1,000 years ago and has created few eruptions during the past several thousand years, resulting in several major lava flows, the most notable being the A. G. Aiken Lava Bed, the Muddy Fork Lava Flows, and the Takh Takh Lava Flow. One of the most recent flows issued from South Butte created the 4.5-mile (7.2 km) long by 0.5-mile (0.80 km) wide A.G. Aiken Lava Bed. Thermal anomalies (hot spots) and gas emissions (including hydrogen sulfide) have occurred especially on the summit plateau since the Great Slide of 1921.

Mount Hood

Mount Hood was last active about 200 years ago, creating pyroclastic flows, lahars, and a well-known lava dome close to its peak called Crater Rock. Between 1856 and 1865, a sequence of steam explosions took place at Mount Hood.

Newberry Volcano

A great deal of volcanic activity has occurred at Newberry Volcano, which was last active about 1,300 years ago. It has one of the largest collections of cinder cones, lava domes, lava flows and fissures in the world.

Medicine Lake Volcano

Medicine Lake Volcano has erupted about eight times in the past 4,000 years and was last active about 1,000 years ago when rhyolite and dacite erupted at Glass Mountain and associated vents near the caldera's eastern rim.

Mount Shasta

Mount Shasta last erupted around 1250 and has been the most active volcano in California for about 4,000 years. Previous claims of a 1786 eruption have been discredited.

Eruptions in the Cascade Range

Eleven of the thirteen volcanoes in the Cascade Range have erupted at least once in the past 4,000 years, and seven have done so in just the past 200 years. The Cascade volcanoes have had more than 100 eruptions over the past few thousand years, many of them explosive eruptions. However, certain Cascade volcanoes can be dormant for hundreds or thousands of years between eruptions, and therefore the great risk caused by volcanic activity in the regions is not always readily apparent.

When Cascade volcanoes do erupt, pyroclastic flows, lava flows, and landslides can devastate areas more than 10 miles (16 km) away; and huge mudflows of volcanic ash and debris, called lahars, can inundate valleys more than 50 miles (80 km) downstream. Falling ash from explosive eruptions can disrupt human activities hundreds of miles downwind, and drifting clouds of fine ash can cause severe damage to jet aircraft even thousands of miles away.

All of the known historical eruptions have occurred in Washington, Oregon and in Northern California. The three most recent were Lassen Peak from 1914 to 1921, a major eruption of Mount St. Helens in 1980, and a minor eruption of Mount St. Helens from 2004 to 2008. In contrast, volcanoes in southern British Columbia, central and southern Oregon are currently dormant. The regions lacking new eruptions keep in touch to positions of fracture zones that offset the Gorda Ridge, Explorer Ridge and the Juan de Fuca Ridge. The volcanoes with historical eruptions include: Mount Rainier, Glacier Peak, Mount Baker, Mount Hood, Lassen Peak, and Mount Shasta.

Renewed volcanic activity in the Cascade Arc, such as the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens, has offered a great deal of evidence about the structure of the Cascade Arc. One effect of the 1980 eruption was a greater knowledge of the influence of landslides and volcanic development in the evolution of volcanic terrain. A vast piece on the north side of Mount St. Helens dropped and formed a jumbled landslide environment several kilometers away from the volcano. Pyroclastic flows and lahars moved across the countryside. Parallel episodes have also happened at Mount Shasta and other Cascade volcanoes in prehistoric times.