From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Online_dating

Online dating, also known as internet dating, virtual dating, or mobile app dating, is a method used by people with a goal of searching for and interacting with potential romantic or sexual partners, via the internet. An online dating service is a company that promotes and provides specific mechanisms for the practice of online dating, generally in the form of dedicated websites or software applications accessible on personal computers or mobile devices connected to the internet. A wide variety of unmoderated matchmaking services, most of which are profile-based with various communication functionalities, is offered by such companies.

Online dating services allow users to become "members" by creating a profile and uploading personal information including (but not limited to) age, gender, sexual orientation, location, and appearance. Most services also encourage members to add photos or videos to their profile. Once a profile has been created, members can view the profiles of other members of the service, using the visible profile information to decide whether or not to initiate contact. Most services offer digital messaging, while others provide additional services such as webcasts, online chat, telephone chat (VOIP), and message boards. Members can constrain their interactions to the online space, or they can arrange a date to meet in person.

A great diversity of online dating services currently exist. Some have a broad membership base of diverse users looking for many different types of relationships. Other sites target highly specific demographics based on features like shared interests, location, religion, sexual orientation or relationship type. Online dating services also differ widely in their revenue streams. Some sites are completely free and depend on advertising for revenue. Others utilize the freemium revenue model, offering free registration and use, with optional, paid, premium services. Still others rely solely on paid membership subscriptions.

Matching algorithms

In 2012, social psychologists Benjamin Karney, Harry Reis, and others published an analysis of online dating in Psychological Science in the Public Interest that concluded that the matching algorithms of online dating services are only negligibly better at matching people than if they were matched at random. In 2014, Kang Zhao at the University of Iowa constructed a new approach based on the algorithms used by Amazon and Netflix, based on recommendations rather than the autobiographical notes of match seekers. Users' activities reflect their tastes and attractiveness, or the lack thereof, they reasoned. This algorithm increases the chances of a response by 40%, the researchers found. E-commerce firms also employ this "collaborative filtering" technique. Nevertheless, it is still not known what the algorithm for finding the perfect match would be.

However, while collaborative filtering and recommender systems have been demonstrated to be more effective than matching systems based on similarity and complementarity, they have also been demonstrated to be highly skewed to the preferences of early users and against racial minorities such as African Americans and Hispanic Americans which led to the rise of niche dating sites for those groups. In 2014, the Better Business Bureau's National Advertising Division criticized eHarmony's claims of creating a greater number of marriages and more durable and satisfying marriages than alternative dating websites, and in 2018, the Advertising Standards Authority banned eHarmony advertisements in the United Kingdom after the company was unable to provide any evidence to verify its advertisements' claims that its website's matching algorithm was scientifically proven to give its users a greater chance of finding long-term intimate relationships.

Trends

Social trends and public opinions

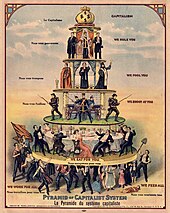

Opinions and usage of online dating services also differ widely. A 2005 study of data collected by the Pew Internet & American Life Project found that individuals are more likely to use an online dating service if they use the Internet for a greater number of tasks, and less likely to use such a service if they are trusting of others. It is possible that the mode of online dating resonates with some participants' conceptual orientation towards the process of finding a romantic partner. That is, online dating sites use the conceptual framework of a "marketplace metaphor" to help people find potential matches, with layouts and functionalities that make it easy to quickly browse and select profiles in a manner similar to how one might browse an online store. Under this metaphor, members of a given service can both "shop" for potential relationship partners and "sell" themselves in hopes of finding a successful match.

Attitudes towards online dating improved visibly between 2005 and 2015, the Pew Research Center found. In particular, the number of people who thought that online dating was a good way to meet people rose from 44% in 2005 to 59% in 2015 whereas those who believed that people who used online dating services were desperate fell from 29% to 23% during the same period. Although only a negligible number of people dated online in 2005, that rose to 11% in 2013 and then 15% in 2015. In particular, the number of American adults who had used an online dating site went from 9% in 2013 to 12% in 2015 while those who used an online dating software application on their mobile phones jumped from 3% to 9% during the same period. This increase was driven mainly by people aged 18 to 24, for whom usage almost tripled. At the same time, usage among those between the ages of 55 and 64 doubled. People in their mid-30s to mid-50s all saw noticeable increases in usage, but people aged 25 to 34 saw no change. Nevertheless, only one in three had actually gone out on a date with someone they met online. About one in five, especially women, at 30%, compared to 16% for men, asked for help with their online profile. Only five out of a hundred said they were married to or in a committed long-term relationship with someone they met online. For comparison, 88% of Americans who were with their current spouse or partner for no more than five years said their met their mates offline.

Online daters may have more liberal social attitudes compared to the general population in the United States. According to a 2015 study by the Pew Research Center, people who had used online dating services had a higher opinion of such services than those who had not. 80% of the users said that online dating sites are a good way to meet potential partners, compared to 55% of non-users. In addition, online daters felt that online dating is easier and more efficient than other methods (61%), and gives access to a larger pool of potential partners (62%), compared to 44% and 50% of non-users, respectively. Meanwhile, 60% of non-users thought that online dating was a more dangerous way of meeting people and 24% deemed people who dated online were desperate, compared to 45% and 16% of online daters, respectively. Nevertheless, a similar number of online daters (31%) and non-users (32%) agreed that online dating kept people from settling down. In all, there was little difference among the sexes with regards to their opinions on online dating. Safety was, however, the exception, with 53% of women and 38% of men expressing concern.

It is not clear that social networking websites and online dating services are leading to the formation of long-term intimate relationships more efficiently. In 2000, a majority of U.S. households had personal computers, and in 2001, a majority of U.S. households had internet access. In 1995, Match.com was created, followed by eHarmony in 2000, Myspace and Plenty of Fish in 2003, Facebook and OkCupid in 2004, Zoosk in 2007, and Tinder in 2012. In 2011, the percentage of all U.S. adults who were married declined to a historic low at 51 percent, while from 2007 to 2017 the percentage of U.S. adults living without spouses or partners rose to 42 percent (including 61 percent of adults under the age of 35) because declines in marriage since 1960 (when 72 percent of U.S. adults were married) have not been offset by increases in cohabitation. In 2014, the percentage of U.S. adults above the age of 25 who had never married rose to a record one-fifth (with the rate of growth in the category accelerating since 2000).

Psychologists Douglas T. Kenrick, Sara E. Gutierres, Laurie L. Goldberg, Steven Neuberg, Kristin L. Zierk, and Jacquelyn M. Krones have demonstrated experimentally that following exposure to photographs or stories about desirable potential mates, human subjects decrease their ratings of commitment to their current partners. Social psychologist David Buss has estimated that approximately 30 percent of the men on Tinder are married, and a significant criticism of Facebook has been its effect on its users' marriages. In 2012, Benjamin Karney, Harry Reis, and their co-authors suggested that the availability of a large pool of potential partners "may lead online daters to objectify potential partners and might even undermine their willingness to commit to one of them." In October 2019, a Pew Research Center survey of 4,860 U.S. adults showed that 54 percent of U.S. adults believed that relationships formed through dating sites or apps were just as successful as those that began in person, 38 percent believed these relationships were less successful, while only 5 percent believed them to be more successful.

Noting the research of Karney, Reis, and their co-authors comparing online to offline dating and the research of communications studies scholar Nicole Ellison and her co-authors comparing online dating to comparative shopping, political scientist Robert D. Putnam cited the October 2019 Pew Research Center survey in the afterword to the second edition of Bowling Alone (2020) in expressing skepticism about whether online dating was leading to a greater number of long-term intimate relationships. In October 2021, a representative survey conducted by Savanta ComRes of 2,027 ever-married adults 30 years of age or older in the United Kingdom was released that studied differences in the first marriage divorce rate by whether subjects met their spouse: (1) online; (2) at school or at a post-secondary institution; (3) through family, friends, or neighbors; (4) through work; or (5) at a bar or party. After controlling for age, sex, and occupation, the survey found that for first marriages with weddings since 2000 that spouses who met online had the highest rate of divorce after 3 years of marriage and after 5 years of marriage and the second highest rate of divorce after 7 years of marriage and after 10 years of marriage after spouses who met through work.

Mate preferences and mating strategies

Online dating services offer goldmines of information for social scientists studying human mating behavior.

Data from the Chinese online dating giant Zhenai.com reveals that while men are most interested in how a woman looks, women care more about a man's income. Profession is also quite important. Chinese men favor women working as primary school teachers and nurses while Chinese women prefer men in the IT or finance industry. Women in IT or finance are the least desired. Zhenai enables users to send each other digital "winks." For a man, the more money he earns the more "winks" he receives. For a woman, her income does not matter until the 50,000-yuan mark (US$7,135), after which the number of "winks" falls slightly. Men typically prefer women three years younger than they are whereas women look for men who are three years older on average. However, this changes if the man becomes exceptionally wealthy; the more money he makes the more likely he is to look for younger women.

In general, people in their 20s employ the "self-service dating service" while women in their late 20s and up tend to use the matchmaking service. This is because of the social pressure in China on "leftover women" (Sheng nu), meaning those in their late 20s but still not married. Women who prefer not to ask potentially embarrassing questions – such as whether both spouses will handle household finances, whether or not they will live with his parents, or how many children he wants to have, if any – will get a matchmaker to do it for them. Both sexes prefer matchmakers who are women.

In a 2009 paper, sociologist George Yancey from the University of North Texas observed that prior research from the late 1980s to the early 2000s revealed that African-Americans were the least desired romantic partners compared to all other racial groups in the United States, a fact that is reflected in their relatively low interracial marriage rates. (They were also less likely to form interracial friendships than other groups.) According to data from the U.S. Census, 5.4% of all marriages in the U.S. in 2005 were between people of different races. For his research, Yancey downloaded anonymized data of almost a thousand heterosexual individuals from Yahoo! Personals. He discovered that Internet daters felt lukewarm towards racial exogamy in general. In particular, 45.8% of whites, 32.6% of blacks, 47.6% of Hispanics, and 64.4% of Asians were willing to out-date with any other racial group. Dating members of one's own racial group was the most popular option, at 98.0% for whites, 92.1% for blacks, 93.2% for Hispanics, and 92.2% for Asians. Those who were more willing to out-date than average tended to be younger men. Education was not a predictor of willingness to out-date. This means that the higher interracial marriage rates among the highly educated were due to the fact that higher education provided more opportunities to meet people of different races.

There is, however, great variation along gender lines. In 2008, Cynthia Feliciano, Belinda Robnett, and Golnaz Komaie from the University of California, Irvine, investigated the preferences of online daters long gendered and racial lines by selecting profiles on Yahoo! Personals – then one of the top Internet romance sites in the U.S.– of 6,070 heterosexual individuals, 1558 of whom white, between the ages of 18 and 50 living within 50 miles (80 km) of New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Atlanta. They found that consistent with prior research, including speed-dating studies, women tended to be pickier than men. In fact, while 29% of white men wanted to date only white women, 64% of white women were willing to date white men only. Of those who stated a racial preference, 97% of white men excluded black women, 48% Latinas, and 53% Asian women. In contrast, white men are excluded by 76% of black women, 33% Latinas, and only 11% Asian women. Similarly, 92% of white women exclude black men, 77% exclude Latinos, and 93% exclude Asian men. 71% of black men, 31% of Latinos, and 36% of Asian men excluded white women. In short, after opposite-sex members of their own group, white men were open to dating Asian women, and white women black men than members of other racial or ethnic groups. At the same time, Latinos were generally favored by both white men and women willing to out-date.

Feliciano, Robnett, and Komaie found that white women who described themselves as athletic, average, fit, or slim were more likely to exclude black men than those who considered themselves large, thick, or voluptuous. Body type, however, was not a predictor for white women's avoidance of Asian men, nor was it for the white men's preferences. On the other hand, white men with a particular body type in mind were considerably more likely to exclude black women while women who preferred a particular height were slightly more likely to exclude Asian men. Women who deemed themselves very liberal or liberal were less likely than apolitical, moderate, or conservative women to exclude black men. In contrast, left-leaning white women were slightly more likely to exclude Asian men. Being Jewish was the perfect predictor of black exclusion. All white men and women who identified as Jewish and who had a racial preference excluded blacks, and all white Jewish women also avoided Asian men. White men with a religious preference were four times as likely to exclude black women, and white women with the same were twice as likely to exclude black men. However, religious preferences were not linked to avoiding Asians.

Prior research has shown that in the absence of direct personal contact, one's perception of members of a different group is often shaped by stereotypes, or "cognitive structures that contain the perceiver’s knowledge, beliefs, and expectancies about some human group," which are typically reinforced by mass media. Feliciano, Robnett, and Komaie found some support for this. In particular, white men's exclusion of black women was linked to the perception that black women deviate from (Western) idealized notions of femininity, for example by being bossy, while their favoring Asian women was likely due to the latter's portrayal in the media as "the embodiment of perfect womanhood" and "good wives." On the other hand, white women's exclusion of Asian men correlated with the stereotype that the latter were asexual or lacked masculinity whereas their preferring black men corresponded with the latter's positive portrayal in the media as "independent and respected." Feliciano, Robnett, and Komaie observed that their findings on mate preferences mirrored actual cohabitation and marriage patterns.

In a separate paper from 2011 analyzing the same data set, Cynthia Feliciano and Belinda Robnett found in general, gender was a predictor of openness to dating outside of one's racial or ethnic group, with 74% of women and 58% of men stating a racial preference, though there was considerable variation among each. Latinos were quite open to out-dating, with only 15% of men and 16% of women preferring to date only other Latinos. 45% of black women and 23% of black men would rather not date non-blacks. 6% of Asian women and 21% of Asian men decided against out-dating. In addition, 4% of white women, 8% of black women, 16% of Latino women, and 40% of Asian women wanted to date only outside of their respective race or ethnicity. Therefore, all groups except white women were willing to out-date, albeit with great variations. 55% of Latino men excluded Asian women while 73% of Asian women excluded Latino men. An overwhelming majority of Asians, 94%, excluded blacks. By contrast, 81% of Latinos and 76% of Latinas avoided the same. For blacks willing to out-date, Latinos were most preferred.

In 2018, Elizabeth Bruch and M.E.J. Newman from the University of Michigan published in the journal Science Advances a study of approximately 200,000 heterosexual individuals living in New York City, Chicago, Boston and Seattle, who used a certain "popular, free online-dating service." The researchers were able to discern some general trends in the overall desirability of a given individual. For a man, his desirability increased till the age of 50; for a woman, her desirability declined steeply after the age of 18 till the age of 65. In terms of educational attainment, the more educated a man was, the more desirable he became; for a woman, however, her desirability rose up to the bachelor's degree before declining. Bruch suggested that besides individual preferences and partner availability, this pattern may be due to the fact that by the late 2010s, women were more likely to attend and graduate from university. In order to estimate the desirability of a given individual, the researchers looked at the number of messages they received and the desirability of the senders.

Developmental psychologist Michelle Drouin, who was not involved in the study, told The New York Times this finding is in accordance with theories in psychology and sociology based on biological evolution in that youth is a sign of fertility. She added that women with advanced degrees are often viewed as more focused on their careers than family. Licensed psychotherapist Stacy Kaiser told MarketWatch men typically prefer younger women because "they are more easy to impress; they are more (moldable) in terms of everything from emotional behavior to what type of restaurant to eat at," and because they tend to be "more fit, have less expectations and less baggage." On the other hand, women look for (financial) stability and education, attributes that come with age, said Kaiser. These findings regarding age and attractiveness are consistent with earlier research by the online dating services OKCupid and Zoosk. In an 2010 blog post, OKCupid observed that, "The median 30-year-old man spends as much time messaging teenage girls as he does women his own age." By analyzing data from between 2013 and 2017, OKCupid discovered that 61% what they called "successful" conversations, or those with "at least at four messages back and forth with contact exchange" took place between a man who was older than the woman. In half of these, the man was at least five years older. 2018 data from Zoosk revealed that 60% of men desired younger women, while 56% of younger women felt attracted to older men.

Aided by the text-analysis program Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count, Bruch and Newman discovered that men generally had lower chances of receiving a response after sending more "positively worded" messages. When a man tried to woo a woman more desirable than he was, he received a response 21% of the time; by contrast, when a woman attempted to court a man, she received a reply about half the time. In fact, over 80% of the first messages in the data set obtained for the purposes of the study were from men, and women were highly selective in choosing whom to respond to, a rate of less than 20%. Therefore, studying women's replies yielded much insight into their preferences. Bruch and Newman were also able to establish the existence of dating 'leagues'. Generally speaking, people were able to accurately estimate where they ranked on the dating hierarchy. Very few responded to the messages of people less desirable than they were. Nevertheless, although the probability of a response is low, it is well above zero, and if the other person does respond, it can a self-esteem booster, said Kaiser. Co-author of the study Mark Newman told BBC News, "There is a trade-off between how far up the ladder you want to reach and how low a reply rate you are willing to put up with." Bruch and Newman found that while people spent a lot of time crafting lengthy messages to those they considered to be a highly desirable partner, this hardly made a difference, judging by the response rate. Keeping messages concise is well-advised. Previous studies also suggest that about 70% of the dating profile should be about oneself and the rest about the desired partner.

At least three quarters of the sample surveyed attempted to date aspirationally, meaning they tried to initiate a relationship with someone who was more desirable, 25% more desirable, to be exact. Bruch recommended sending out more greeting messages, noting that people sometimes managed to upgrade their 'league'. Michael Rosenfeld, a sociologist not involved with the study, told The Atlantic, "The idea that persistence pays off makes sense to me, as the online-dating world has a wider choice set of potential mates to choose from. The greater choice set pays dividends to people who are willing to be persistent in trying to find a mate." Using optimal stopping theory, one can show that the best way to select the best potential partner is to reject the first 37%, then pick the one who is better than the previous set. The probability of picking the best potential mate this way is 37%. (This is approximately the reciprocal of Euler's number, . See derivation of the optimal policy.) However, making online contact is only the first step, and indeed, most conversations failed to birth a relationship. As two potential partners interact more and more, the superficial information available from a dating website or smartphone application becomes less important than their characters. Bruch and Newman found that overall, white men and Asian women were the most desired in all the four cities.

Despite being a platform designed to be less centered on physical appearance, OkCupid co-founder Christian Rudder stated in 2009 that the male OkCupid users who were rated most physically attractive by female OkCupid users received 11 times as many messages as the lowest-rated male users did, the medium-rated male users received about four times as many messages, and the one-third of female users who were rated most physically attractive by the male users received about two-thirds of all messages sent by male users. Data released by Tinder has shown that of the 1.6 billion swipes it records per day, only 26 million result in matches (a match rate of approximately only 1.63%), despite users logging into the app on average 11 times per day, with male user sessions averaging 7.2 minutes and female user sessions averaging 8.5 minutes (or 79.2 minutes and 93.5 minutes per day respectively). Also, a Tinder user interviewed anonymously in an article published in the December 2018 issue of The Atlantic estimated that only one in 10 of their matches actually resulted in an exchange of messages with the other user they were matched with, with another anonymous Tinder user saying, "Getting right-swiped is a good ego boost even if I have no intention of meeting someone." According to a former company product manager, the majority of female Bumble users typically set a floor height of six feet for male users which limits their matching opportunities to only 15% of the population.

According to University of Texas at Austin psychologist David Buss, "Apps like Tinder and OkCupid give people the impression that there are thousands or millions of potential mates out there. One dimension of this is the impact it has on men's psychology. When there is ... a perceived surplus of women, the whole mating system tends to shift towards short-term dating," and there is a feeling of disconnect when choosing future partners. In addition, the cognitive process identified by psychologist Barry Schwartz as the "paradox of choice" (also referred to as "choice overload" or "fear of a better option") was cited in an article published in The Atlantic that suggested that the appearance of an abundance of potential partners causes online daters to be less likely to choose a partner and be less satisfied with their choices of partners.

Before 2012, most online dating services matched people according to their autobiographical information, such as interests, hobbies, future plans, among other things. But the advent of Tinder that year meant that first impressions could play a crucial role. For social scientists studying human courtship behavior, Tinder offers a much simpler environment than its predecessors. In 2016, Gareth Tyson of the Queen Mary University of London and his colleagues published a paper analyzing the behavior of Tinder users in New York City and London. In order to minimize the number of variables, they created profiles of white heterosexual people only. For each sex, there were three accounts using stock photographs, two with actual photographs of volunteers, one with no photos whatsoever, and one that was apparently deactivated. The researchers pointedly only used pictures of people of average physical attractiveness. Tyson and his team wrote an algorithm that collected the biographical information of all the matches, liked them all, then counted the number of returning likes.

They found that men and women employed drastically different mating strategies. Men liked a large proportion of the profiles they viewed, but received returning likes only 0.6% of the time; women were much more selective but received matches 10% of the time. Men received matches at a much slower rate than women. Once they received a match, women were far more likely than men to send a message, 21% compared to 7%, but they took more time before doing so. Tyson and his team found that for the first two-thirds of messages from each sex, women sent them within 18 minutes of receiving a match compared to five minutes for men. Men's first messages had an average of a dozen characters, and were typical simple greetings; by contrast, initial messages by women averaged 122 characters.

Tyson and his collaborators found that the male profiles that had three profile pictures received 238 matches while the male profiles with only one profile picture received only 44 matches (or approximately a 5 to 1 ratio). Additionally, male profiles that had a biography received 69 matches while those without received only 16 matches (or approximately a 4 to 1 ratio). By sending out questionnaires to frequent Tinder users, the researchers discovered that the reason why men tended to like a large proportion of the women they saw was to increase their chances of getting a match. This led to a feedback loop in which men liked more and more of the profiles they saw while women could afford to be even more selective in liking profiles because of a greater probability of a match. The mathematical limit of the feedback loop occurs when men like all profiles they see while women find a match whenever they like a profile. It was not known whether some evolutionarily stable strategy has emerged, nor has Tinder revealed such information.

Tyson and his team found that even though the men-to-women ratio of their data set was approximately one, the male profiles received 8,248 matches in total while the female profiles received only 532 matches in total because the vast majority of the matches for both the male and female profiles came from male profiles (with 86 percent of the matches for the male profiles alone coming from other male profiles), leading the researchers to conclude that homosexual men were "far more active in liking than heterosexual women." On the other hand, the deactivated male account received all of its matches from women. The researchers were not sure why this happened.

Niche dating sites

Sites with specific demographics have become popular as a way to narrow the pool of potential matches. Successful niche sites pair people by race, sexual orientation or religion. In March 2008, the top 5 overall sites held 7% less market share than they did one year ago while the top sites from the top five major niche dating categories made considerable gains. Niche sites cater to people with special interests, such as sports fans, racing and automotive fans, medical or other professionals, people with political or religious preferences, people with medical conditions, or those living in rural farm communities.

Some dating services have been created specifically for those living with HIV and other venereal diseases in an effort to eliminate the need to lie about one's health in order to find a partner. Public health officials in Rhode Island and Utah claimed in 2015 that Tinder and similar apps were responsible for uptick of such conditions.

Economic trends

Although some sites offer free trials and/or profiles, most memberships can cost upwards of $60 per month. In 2008, online dating services in the United States generated $957 million in revenue.

Most free dating websites depend on advertising revenue, using tools such as Google AdSense and affiliate marketing. Since advertising revenues are modest compared to membership fees, this model requires numerous page views to achieve profitability. However, Sam Yagan describes dating sites as ideal advertising platforms because of the wealth of demographic data made available by users.

In November 2023, the stock prices of Match Group and Bumble were down 31% and 35% on the year respectively, continuing a more than two-year decline since the latter's initial public offering in February 2021 and after posting declines more than double that of the S&P 500 during the 2022 stock market decline. In addition to price increases, slowing paid user growth, and flattening app download rates following the end of the COVID-19 lockdowns, assessments among financial analysts of an oversaturated market and growing skepticism about dating app features and algorithms and consumer satisfaction with the services contributed to the declines.

Online matchmaking services

In 2008, a variation of the online dating model emerged in the form of introduction sites, where members have to search and contact other members, who introduce them to other members whom they deem compatible. Introduction sites differ from the traditional online dating model, and attracted many users and significant investor interest.

In China, the number of separations per a thousand couples doubled, from 1.46 in 2006 to about three in 2016, while the number of actual divorces continues to rise, according to the Ministry of Civil Affairs. Demand for online dating services among divorcees keeps growing, especially in the large cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen and Guangzhou. In addition, more and more people are expected to use online dating and matchmaking services as China continues to urbanize in the late 2010s and 2020s.

Reception

In 2016, Consumer Reports surveyed approximately 115,000 online dating service subscribers across multiple platforms and found that while 44 percent of survey respondents stated that usage of online dating services led to a serious long-term intimate relationship or marriage, a subset of approximately 9,600 subscribers that had used at least one online dating service within the previous two years rated satisfaction with the services they used lower than Consumer Reports surveys of consumer satisfaction with technical support services and rated satisfaction with free online dating services as slightly more satisfactory than services with paid subscriptions.

Trust and safety issues

As online dating services are not required to routinely conduct background checks on members, it is possible for profile information to be misrepresented or falsified. Also, there may be users on dating services that have illicit intentions (i.e. date rape, procurement, etc).

OKCupid once introduced a real name policy, but that was later taken removed due to unpopularity with its users.

Only some online dating services are providing important safety information such as STD status of its users or other infectious diseases, but many do not.

Some online dating services which are popular amongst members of queer communities are sometimes used by people as a means of meeting these audiences for the purpose of gaybashing or trans bashing.

A form of misrepresentation is that members may lie about their height, weight, age, or marital status in an attempt to market or brand themselves in a particular way. Users may also carefully manipulate profiles as a form of impression management. Online daters have raised concerns about ghosting, the practice of ceasing all communication with a person without explaining why. Ghosting appears to be becoming more common. Various explanations have been suggested, but social media is often blamed, as are dating apps and the relative anonymity and isolation in modern-day dating and hookup culture, which make it easier to behave poorly with few social repercussions.

Online dating site members may try to balance an accurate representation with maintaining their image in a desirable way. One study found that nine out of ten participants had lied on at least one attribute, though lies were often slight; weight was the most lied about attribute, and age was the least lied about. Furthermore, knowing a large amount of superficial information about a potential partner's interests may lead to a false sense of security when meeting up with a new person. Gross misrepresentation may be less likely on matrimonials sites than on casual dating sites.

Some profiles may not even represent real humans but rather they may be fake "bait profiles" placed online by site owners to attract new paying members, or "spam profiles" created by advertisers to market services and products.

Opinions on regarding the safety of online dating are mixed. Over 50% of research participants in a 2011 study did not view online dating as a dangerous activity, whereas 43% thought that online dating involved risk. Date rape is a form of acquaintance rape and dating violence. The two phrases are often used interchangeably, but date rape specifically refers to a rape in which there has been some sort of romantic or potentially sexual relationship between the two parties. Acquaintance rape also includes rapes in which the victim and perpetrator have been in a non-romantic, non-sexual relationship, for example as co-workers or neighbors. According to the United States Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), date rapes are among the most common forms of rape cases. Date rape most commonly takes place among college students when alcohol is involved or date rape drugs are taken. One of the most targeted groups are women between the ages of 16 and 24.

In response to these issues, over 120 Facebook groups named Are We Dating The Same Guy? were created where women share red flags about men and check that he is not dating another person. It is done by taking screenshots of a man's dating profile and posting it onto her city's designated Facebook group, asking "any tea?". Other users in the group will then share information about the man and share warnings. The groups are moderated by volunteers, and have been described as a feminist group.

Billing complaints

Online subscription-based services can suffer from complaints about billing practices. Some online dating service providers may have fraudulent membership fees or credit card charges. Some sites do not allow members to preview available profiles before paying a subscription fee. Furthermore, different functionalities may be offered to members who have paid or not paid for subscriptions, resulting in some confusion around who can view or contact whom.

Consolidation within the online dating industry has led to different newspapers and magazines now advertising the same website database under different names. In the UK, for example, Time Out ("London Dating"), The Times ("Encounters"), and The Daily Telegraph ("Kindred Spirits"), all offer differently named portals to the same service—meaning that a person who subscribes through more than one publication has unwittingly paid more than once for access to the same service.

Imbalanced gender ratios

Little is known about the sex ratio controlled for age. eHarmony's membership is about 57% female and 43% male, whereas the ratio at Match.com is about the reverse of that. On specialty niche websites where the primary demographic is male, there is typically a very unbalanced ratio of male to female or female to male. As of June 2015, 62% of Tinder users were male and 38% were female.

Studies have suggested that men are far more likely to send messages on dating sites than women. In addition, men tend to message the most attractive women regardless of their own attractiveness. This leads to the most attractive women on these sites receiving an overwhelming number of messages, which can in some cases result in them leaving the site.

There is some evidence that there may be differences in how women online rate male attractiveness as opposed to how men rate female attractiveness. The distribution of ratings given by men of female attractiveness appears to be the normal distribution, while ratings of men given by women is highly skewed, with 80% of men rated as below average.

Allegations of discrimination

Gay rights groups have complained that certain websites that restrict their dating services to heterosexual couples are discriminating against homosexuals. Homosexual customers of the popular eHarmony dating website have made many attempts to litigate discriminatory practices. eHarmony was sued in 2007 by a lesbian claiming that "[s]uch outright discrimination is hurtful and disappointing for a business open to the public in this day and age." In light of discrimination by sexual orientation by dating websites, some services such as GayDar.net and Chemistry.com cater more to homosexual dating.

Lawsuits filed against online dating services

A 2011 class action lawsuit alleged Match.com failed to remove inactive profiles, did not accurately disclose the number of active members, and does not police its site for fake profiles; the inclusion of expired and spam profiles as valid served to both artificially inflate the total number of profiles and camouflage a skewed gender ratio in which active users were disproportionately single males. The suit claimed up to 60 percent were inactive profiles, fake or fraudulent users. Some of the spam profiles were alleged to be using images of porn actresses, models, or people from other dating sites. Former employees alleged Match routinely and intentionally over-represented the number of active members on the website and a huge percentage were not real members but 'filler profiles'.

A 2012 class action against Successful Match ended with a November 2014 California jury award of $1.4 million in compensatory damages and $15 million in punitive damages. SuccessfulMatch operated a dating site for people with STDs, PositiveSingles, which it advertised as offering a "fully anonymous profile" which is "100% confidential". The company failed to disclose that it was placing those same profiles on a long list of affiliate site domains such as GayPozDating.com, AIDSDate.com, HerpesInMouth.com, ChristianSafeHaven.com, MeetBlackPOZ.com, HIVGayMen.com, STDHookup.com, BlackPoz.com, and PositivelyKinky.com. This falsely implied that those users were black, Christian, gay, HIV-positive or members of other groups with which the registered members did not identify. The jury found PositiveSingles guilty of fraud, malice, and oppression as the plaintiffs' race, sexual orientation, HIV status, and religion were misrepresented by exporting each dating profile to niche sites associated with each trait.

In 2013, a former employee sued adultery website Ashley Madison claiming repetitive strain injuries as creating 1000 fake profiles in one three week span "required an enormous amount of keyboarding" which caused the worker to develop severe pain in her wrists and forearms. AshleyMadison's parent company, Avid Life Media, countersued in 2014, alleging the worker kept confidential documents, including copies of her "work product and training materials." The firm claimed the fake profiles were for "quality assurance testing" to test a new Brazilian version of the site for "consistency and reliability."

In January 2014, an already-married Facebook user attempting to close a pop-up advertisement for Zoosk.com found that one click instead copied personal info from her Facebook profile to create an unwanted online profile seeking a mate, leading to a flood of unexpected responses from amorous single males.

In 2014, It's Just Lunch International was the target of a New York class action alleging unjust enrichment as IJL staff relied on a uniform, misleading script which informed prospective customers during initial interviews that IJL already had at least two matches in mind for those customers' first dates regardless of whether or not that was true.

In 2014, the US Federal Trade Commission fined UK-based JDI Dating (a group of 18 websites, including Cupidswand.com and FlirtCrowd.com) over US$600000, finding that "the defendants offered a free plan that allowed users to set up a profile with personal information and photos. As soon as a new user set up a free profile, he or she began to receive messages that appeared to be from other members living nearby, expressing romantic interest or a desire to meet. However, users were unable to respond to these messages without upgrading to a paid membership ... [t]he messages were almost always from fake, computer-generated profiles — 'Virtual Cupids' — created by the defendants, with photos and information designed to closely mimic the profiles of real people." The FTC also found that paid memberships were being renewed without client authorisation.

On June 30, 2014, co-founder and former marketing vice president of Tinder, Whitney Wolfe, filed a sexual harassment and sex discrimination suit in Los Angeles County Superior Court against IAC-owned Match Group, the parent company of Tinder. The lawsuit alleged that her fellow executives and co-founders Rad and Mateen had engaged in discrimination, sexual harassment, and retaliation against her, while Tinder's corporate supervisor, IAC's Sam Yagan, did nothing. IAC suspended CMO Mateen from his position pending an ongoing investigation, and stated that it "acknowledges that Mateen sent private messages containing 'inappropriate content,' but it believes Mateen, Rad and the company are innocent of the allegations". In December 2018, The Verge reported that Tinder had dismissed Rosette Pambakian, the company's vice president of marketing and communication who had accused Tinder's former CEO Greg Blatt of sexual assault, along with several other employees who were part of the group of Tinder employees who had previously sued the Match Group for $2 billion.

Government regulation

U.S. government regulation of dating services began with the International Marriage Broker Regulation Act (IMBRA) which took effect in March 2007 after a federal judge in Georgia upheld a challenge from the dating site European Connections. The law requires dating services meeting specific criteria—including having as their primary business to connect U.S. citizens/residents with foreign nationals—to conduct, among other procedures, sex offender checks on U.S. customers before contact details can be provided to the non-U.S. citizen. In 2008, the state of New Jersey passed a law which requires the sites to disclose whether they perform background checks.

In the People's Republic of China, using a transnational matchmaking agency involving a monetary transaction is illegal. The Philippines prohibits the business of organizing or facilitating marriages between Filipinas and foreign men under the Republic Act 6955 (the Anti-Mail-Order Bride Law) of June 13, 1990; this law is routinely circumvented by basing mail-order bride websites outside the country.

Singapore's Social Development Network is the governmental organization facilitating dating activities in the country. Singapore's government has actively acted as a matchmaker for singles for the past few decades, and thus only 4% of Singaporeans have ever used an online dating service, despite the country's high rate of internet penetration.

In December 2010, a New York State Law called the "Internet Dating Safety Act" (S5180-A) went into effect that requires online dating sites with customers in New York State to warn users not to disclose personal information to people they do not know.