The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined is a 2011 book by Steven Pinker, in which the author argues that violence in the world has declined both in the long run and in the short run and suggests explanations as to why this has occurred. The book uses data simply documenting declining violence across time and geography. This paints a picture of massive declines in the violence of all forms, from war, to improved treatment of children. He highlights the role of nation-state monopolies on force, of commerce (making other people become more valuable alive than dead), of increased literacy and communication (promoting empathy), as well as a rise in a rational problem-solving orientation as possible causes of this decline in violence. He notes that paradoxically, our impression of violence has not tracked this decline, perhaps because of increased communication, and that further decline is not inevitable, but is contingent on forces harnessing our better motivations such as empathy and increases in reason.

Thesis

The book's title was taken from the ending of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln's first inaugural address. Pinker uses the phrase as a metaphor for four human motivations – empathy, self-control, the "moral sense", and reason – that, he writes, can "orient us away from violence and towards cooperation and altruism."

Pinker presents a large amount of data (and statistical analysis thereof) that, he argues, demonstrate that violence has been in decline over millennia and that the present is probably the most peaceful time in the history of the human species. The decline in violence, he argues, is enormous in magnitude, visible on both long and short time scales and found in many domains including military conflict, homicide, genocide, torture, criminal justice, and treatment of children, homosexuals, animals and racial and ethnic minorities. He stresses that "The decline, to be sure, has not been smooth; it has not brought violence down to zero; and it is not guaranteed to continue."

Pinker argues that the radical declines in violent behavior that he documents do not result from major changes in human biology or cognition. He specifically rejects the view that humans are necessarily violent, and thus have to undergo radical change in order to become more peaceable. However, Pinker also rejects what he regards as the simplistic nature versus nurture argument, which would imply that the radical change must therefore have come purely from external "(nurture)" sources. Instead, he argues that: "The way to explain the decline of violence is to identify the changes in our cultural and material milieu that have given our peaceable motives the upper hand."

Pinker identifies five "historical forces" that have favored "our peaceable motives" and "have driven the multiple declines in violence". They are:

- The Leviathan – the rise of the modern nation-state and judiciary "with a monopoly on the legitimate use of force", which can defuse the [individual] temptation of exploitative attack, inhibit the impulse for revenge and circumvent self-serving biases.

- Commerce – the rise of technological progress [allowing] the exchange of goods and services over longer distances and larger groups of trading partners, so that other people become more valuable alive than dead and are less likely to become targets of demonization and dehumanization.

- Feminization – increasing respect for the interests and values of women.

- Cosmopolitanism – the rise of forces such as literacy, mobility, and mass media, which can prompt people to take the perspectives of people unlike themselves and to expand their circle of sympathy to embrace them.

- The Escalator of Reason – an intensifying application of knowledge and rationality to human affairs which can force people to recognize the futility of cycles of violence, to ramp down the privileging of their own interests over others and to reframe violence as a problem to be solved rather than a contest to be won." Pinker credits Peter Singer for the metaphor "escalator of reason".

Outline

The first section of the book, chapters 2 through 7, seeks to demonstrate and to analyze historical trends related to declines of violence on different scales. Chapter 8 discusses five "inner demons" – psychological systems that can lead to violence. Chapter 9 examines four "better angels" or motives that can incline people away from violence. The last chapter examines the five historical forces listed above that have led to declines in violence.

Six trends of declining violence (Chapters 2 through 7)

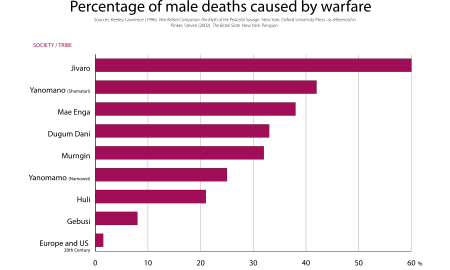

- The Pacification Process: Pinker describes this as the transition from the anarchy of hunting, gathering, and horticultural societies to the first agricultural civilizations with cities and governments, beginning around five thousand years ago which brought a reduction in the chronic raiding and feuding that characterized life in a state of nature and a more or less fivefold decrease in rates of violent death.

- The Civilizing Process: Pinker argues that "between the late Middle Ages and the 20th century, European countries saw a tenfold-to-fiftyfold decline in their rates of homicide." He attributes the idea of the Civilizing Process to the sociologist Norbert Elias, who attributed this surprising decline to the consolidation of a patchwork of feudal territories into large kingdoms with centralized authority and an infrastructure on commerce.

- The Humanitarian Revolution – Pinker attributes this term and concept to the historian Lynn Hunt. He says this revolution "unfolded on the [shorter] scale of centuries and took off around the time of the Age of Reason and the European Enlightenment in the 17th and 18th centuries." Although, he also points to historical antecedents and to "parallels elsewhere in the world", he writes: "It saw the first organized movements to abolish slavery, dueling, judicial torture, superstitious killing, sadistic punishment, and cruelty to animals, together with the first stirrings of systematic pacifism."

- The Long Peace: a term he attributes to the historian John Lewis Gaddis's The Long Peace: Inquiries into the history of the Cold War. Pinker states this fourth "major transition" took place after the end of World War II. During it, he says, the great powers, and the developed states in general, have stopped waging war on one another.

- The New Peace: Pinker calls this trend "more tenuous", but since the end of the Cold War in 1989, organized conflicts of all kinds – civil wars, genocides, repression by autocratic governments, and terrorist attacks – have declined throughout the world.

- The Rights Revolutions: The postwar period has seen, Pinker argues, "a growing revulsion against aggression on smaller scales, including violence against ethnic minorities, women, children, homosexuals, and animals. These spin-offs from the concept of human rights – civil rights, women's rights, children's rights, gay rights, and animal rights – were asserted in a cascade of movements from the late 1950s to the present day."

Five inner demons (Chapter 8)

Pinker rejects what he calls the "Hydraulic Theory of Violence" – the idea "that humans harbor an inner drive toward aggression (a death instinct or thirst for blood), which builds up inside us and must periodically be discharged. Nothing could be further from contemporary scientific understanding of the psychology of violence." Instead, he argues, research suggests that "aggression is not a single motive, let alone a mounting urge. It is the output of several psychological systems that differ in their environmental triggers, their internal logic, their neurological basis, and their social distribution." He examines five such systems:

- Predatory or Practical Violence: violence deployed as a practical means to an end.

- Dominance: the urge for authority, prestige, glory, and power. Pinker argues that dominance motivations can occur within individuals and coalitions of racial, ethnic, religious, or national groups.

- Revenge: the moralistic urge toward retribution, punishment, and justice.

- Sadism: the deliberate infliction of pain for no purpose but to enjoy a person's suffering.

- Ideology: a shared belief system, usually involving a vision of utopia, that justifies unlimited violence in pursuit of unlimited good.

Four better angels (Chapter 9)

Pinker examines four motives that can orient [humans] away from violence and towards cooperation and altruism. He identifies:

- Empathy: which prompts us to feel the pain of others and to align their interests with our own.

- Self-Control: which allows us to anticipate the consequences of acting on our impulses and to inhibit them accordingly.

- The Moral Sense: which sanctifies a set of norms and taboos that govern the interactions among people in a culture. These sometimes decrease violence but can also increase it when the norms are tribal, authoritarian, or puritanical.

- Reason: which allows us to extract ourselves from our parochial vantage points.

In this chapter Pinker also examines and partially rejects the idea that humans have evolved in the biological sense to become less violent.

Influences

Because of the interdisciplinary nature of the book, Pinker uses a range of sources from different fields. Particular attention is paid to philosopher Thomas Hobbes who Pinker argues has been undervalued. Pinker's use of "un-orthodox" thinkers follows directly from his observation that the data on violence contradict our current expectations. In an earlier work, Pinker characterized the general misunderstanding concerning Hobbes:

Hobbes is commonly interpreted as proposing that man in a state of nature was saddled with an irrational impulse for hatred and destruction. In fact his analysis is more subtle, and perhaps even more tragic for he showed how the dynamics of violence fall out of interactions among rational and self-interested agents.

Pinker also references ideas from occasionally overlooked contemporary academics, for example the works of political scientist John Mueller and sociologist Norbert Elias, among others. The extent of Elias's influence on Pinker can be adduced from the title of Chapter 3, which is taken from the title of Elias's seminal The Civilizing Process. Pinker also draws upon the work of international relations scholar Joshua Goldstein. They co-wrote a New York Times op-ed article titled "War Really Is Going Out of Style" that summarizes many of their shared views, and appeared together at Harvard's Institute of Politics to answer questions from academics and students concerning their similar thesis.

Reception

Praise

Bill Gates considers the book one of the most important books he has ever read, and on the BBC radio program Desert Island Discs he selected the book as the one he would take with him to a deserted island. He has written that "Steven Pinker shows us ways we can make those positive trajectories a little more likely. That's a contribution, not just to historical scholarship, but to the world." After Gates recommended the book as a graduate present in May 2017, the book re-entered the bestseller list.

The philosopher Peter Singer gave the book a positive review in The New York Times. Singer concludes: "[It] is a supremely important book. To have command of so much research, spread across so many different fields, is a masterly achievement. Pinker convincingly demonstrates that there has been a dramatic decline in violence, and he is persuasive about the causes of that decline."

Political scientist Robert Jervis, in a long review for The National Interest, states that Pinker "makes a case that will be hard to refute. The trends are not subtle – many of the changes involve an order of magnitude or more. Even when his explanations do not fully convince, they are serious and well-grounded."

In a review for The American Scholar, Michael Shermer writes, "Pinker demonstrates that long-term data trumps anecdotes. The idea that we live in an exceptionally violent time is an illusion created by the media's relentless coverage of violence, coupled with our brain's evolved propensity to notice and remember recent and emotionally salient events. Pinker's thesis is that violence of all kinds – from murder, rape, and genocide to the spanking of children to the mistreatment of blacks, women, gays, and animals – has been in decline for centuries as a result of the civilizing process... Picking up Pinker's 832-page opus feels daunting, but it's a page-turner from the start."

In The Guardian, Cambridge University political scientist David Runciman writes, "I am one of those who like to believe that... the world is just as dangerous as it has always been. But Pinker shows that for most people in most ways it has become much less dangerous." Runciman concludes "everyone should read this astonishing book."

In a later review for The Guardian, written when the book was shortlisted for the Royal Society Winton Prize for Science Books, Tim Radford wrote, "in its confidence and sweep, the vast timescale, its humane standpoint and its confident world-view, it is something more than a science book: it is an epic history by an optimist who can list his reasons to be cheerful and support them with persuasive instances.... I don't know if he's right, but I do think this book is a winner."

Adam Lee writes, in a blog review for Big Think, that "even people who are inclined to reject Pinker's conclusions will sooner or later have to grapple with his arguments."

In a long review in The Wilson Quarterly, psychologist Vaughan Bell calls it "an excellent exploration of how and why violence, aggression, and war have declined markedly, to the point where we live in humanity's most peaceful age.... [P]owerful, mind changing, and important."

In a long review for the Los Angeles Review of Books, anthropologist Christopher Boehm, Professor of Biological Sciences at the University of Southern California and co-director of the USC Jane Goodall Research Center, called the book "excellent and important."

Political scientist James Q. Wilson, in The Wall Street Journal, called the book "a masterly effort to explain what Mr. Pinker regards as one of the biggest changes in human history: We kill one another less frequently than before. But to give this project its greatest possible effect, he has one more book to write: a briefer account that ties together an argument now presented in 800 pages and that avoids the few topics about which Mr. Pinker has not done careful research." Specifically, the assertions to which Wilson objected were Pinker's writing that (in Wilson's summation), "George W. Bush 'infamously' supported torture; John Kerry was right to think of terrorism as a 'nuisance'; 'Palestinian activist groups' have disavowed violence and now work at building a 'competent government'. Iran will never use its nuclear weapons... [and] Mr. Bush... is 'unintellectual.'"

Brenda Maddox, in The Telegraph, called the book "utterly convincing" and "well-argued".

Clive Cookson, reviewing it in the Financial Times, called it "a marvelous synthesis of science, history and storytelling, demonstrating how fortunate the vast majority of us are today to experience serious violence only through the mass media."

The science journalist John Horgan called it "a monumental achievement" that "should make it much harder for pessimists to cling to their gloomy vision of the future" in a largely positive review in Slate.

In The Huffington Post, Neil Boyd, Professor and Associate Director of the School of Criminology at Simon Fraser University, strongly defended the book against its critics, saying:

While there are a few mixed reviews (James Q. Wilson in the Wall Street Journal comes to mind), virtually everyone else either raves about the book or expresses something close to ad hominem contempt and loathing... At the heart of the disagreement are competing conceptions of research and scholarship, perhaps epistemology itself. How are we to study violence and to assess whether it has been increasing or decreasing? What analytic tools do we bring to the table? Pinker, sensibly enough chooses to look at the best available evidence regarding the rate of violent death over time, in pre-state societies, in medieval Europe, in the modern era, and always in a global context; he writes about inter-state conflicts, the two world wars, intrastate conflicts, civil wars, and homicides. In doing so, he takes a critical barometer of violence to be the rate of homicide deaths per 100,000 citizens... Pinker's is a remarkable book, extolling science as a mechanism for understanding issues that are all too often shrouded in unstated moralities, and highly questionable empirical assumptions. Whatever agreements or disagreements may spring from his specifics, the author deserves our respect, gratitude, and applause."

The book also saw positive reviews from The Spectator, and The Independent.

Criticism

Statistician and philosophical essayist Nassim Nicholas Taleb was the first scholar to challenge Pinker's analysis of the data on war, after first corresponding with Pinker. "Pinker doesn't have a clear idea of the difference between science and journalism, or the one between rigorous empiricism and anecdotal statements. Science is not about making claims about a sample, but using a sample to make general claims and discuss properties that apply outside the sample." In a reply, Pinker denied that his arguments had any similarity to "great moderation" arguments about financial markets, and stated that "Taleb's article implies that Better Angels consists of 700 pages of fancy statistical extrapolations which lead to the conclusion that violent catastrophes have become impossible... [but] the statistics in the book are modest and almost completely descriptive" and "the book explicitly, adamantly, and repeatedly denies that major violent shocks cannot happen in the future." Taleb, with statistician and probabilist Pasquale Cirillo, went on to publish an article in the journal Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications that proposes a new methodology for drawing inferences about power-law relationships. In their reanalysis of the data, they find no decline in the lethality of war.

Following the publication of Cirillo and Taleb's article, a growing literature has focused on the claims about the decline of war in Better Angels. In a 2018 article in the journal Science Advances, computer scientist Aaron Clauset explored data on the onset and lethality of wars from 1815 to the present and found that the apparent trends described by Pinker, including the "long peace", were plausibly the result of chance variation. Clauset concluded that recent trends would have to continue for another 100 to 140 years before any statistically significant trend would become evident. A team of scholars from the University of Oslo and the Peace Research Institute Oslo, led by mathematician Céline Cunen, explored the statistical assumptions underpinning Clauset's conclusions. While they reproduced Clauset's result when the data on the lethality of war were assumed to conform to a power-law distribution, as they typically are in the conflict literature they found that a more flexible distribution, the inverse Burr distribution, provided a better fit to the data. Based on this change, they argued for a decrease in the lethality of war after about 1950.

In the first book-length response to Pinker's claims about trends in the data, political scientist Bear Braumoeller explored trends in the initiation of both interstate wars and interstate uses of force, the lethality of wars, and the impact of other phenomena commonly thought to cause conflict. The latter tests represented a new statistical implication of Pinker's claim – that the causes of war in the past had lost their potency over time. Braumoeller found no evidence of consistent upward or downward trends in any of these phenomena, with the exception of interstate uses of force, which steadily increased prior to the end of the Cold War and declined thereafter. Braumoeller argues that these patterns of conflict are much more consistent with the spread of international orders, such as the Concert of Europe and the liberal international order, than with the gradual victory of Pinker's "better angels".

R. Brian Ferguson, professor of Anthropology at Rutgers University–Newark, has challenged Pinker's archaeological evidence for the frequency of war in prehistoric societies, which he contends "consists of cherry-picked cases with high casualties, clearly unrepresentative of history in general." To Ferguson,

[b]y considering the total archaeological record of prehistoric populations of Europe and the Near East up to the Bronze Age, evidence clearly demonstrates that war began sporadically out of warless condition, and can be seen in varying trajectories in different areas, to develop over time as societies become larger, more sedentary, more complex, more bounded, more hierarchical, and in one critically important region, impacted by an expanding state.

Ferguson's examination contradicts Pinker's claim that violence has declined under civilization, indicating the opposite is true.

Despite recommending the book as worth reading, the economist Tyler Cowen was skeptical of Pinker's analysis of the centralization of the use of violence in the hands of the modern nation state.

In his review of the book in Scientific American, psychologist Robert Epstein criticizes Pinker's use of relative violent death rates, that is, of violent deaths per capita, as an appropriate metric for assessing the emergence of humanity's "better angels". Instead, Epstein believes that the correct metric is the absolute number of deaths at a given time. Epstein also accuses Pinker of an over-reliance on historical data, and argues that he has fallen prey to confirmation bias, leading him to focus on evidence that supports his thesis while ignoring research that does not.

Several negative reviews have raised criticisms related to Pinker's humanism and atheism. John N. Gray, in a critical review of the book in Prospect, writes, "Pinker's attempt to ground the hope of peace in science is profoundly instructive, for it testifies to our enduring need for faith."

New York Times columnist Ross Douthat, while "broadly convinced by the argument that our current era of relative peace reflects a longer term trend away from violence, and broadly impressed by the evidence that Pinker marshals to support this view", offered a list of criticisms and concludes Pinker assumes almost all the progress starts with "the Enlightenment, and all that came before was a long medieval dark."

Theologian David Bentley Hart wrote that "one encounters [in Pinker's book] the ecstatic innocence of a faith unsullied by prudent doubt." Furthermore, he says, "it reaffirms the human spirit's lunatic and heroic capacity to believe a beautiful falsehood, not only in excess of the facts, but in resolute defiance of them." Hart continues:

In the end, what Pinker calls a "decline of violence" in modernity actually has been, in real body counts, a continual and extravagant increase in violence that has been outstripped by an even more exorbitant demographic explosion. Well, not to put too fine a point on it: So what? What on earth can he truly imagine that tells us about "progress" or "Enlightenment" or about the past, the present, or the future? By all means, praise the modern world for what is good about it, but spare us the mythology.

Craig S. Lerner, a professor at George Mason University School of Law, in an appreciative but ultimately negative review in the Claremont Review of Books does not dismiss the claim of declining violence, writing, "let's grant that the 65 years since World War II really are among the most peaceful in human history, judged by the percentage of the globe wracked by violence and the percentage of the population dying by human hand", but disagrees with Pinker's explanations and concludes that "Pinker depicts a world in which human rights are unanchored by a sense of the sacredness and dignity of human life, but where peace and harmony nonetheless emerge. It is a future – mostly relieved of discord, and freed from an oppressive God – that some would regard as heaven on earth. He is not the first and certainly not the last to entertain hopes disappointed so resolutely by the history of actual human beings." In a sharp exchange in the correspondence section of the Spring 2012 issue, Pinker attributes to Lerner a "theo-conservative agenda" and accuses him of misunderstanding a number of points, notably Pinker's repeated assertion that "historical declines of violence are 'not guaranteed to continue'." Lerner, in his response, says Pinker's "misunderstanding of my review is evident from the first sentence of his letter" and questions Pinker's objectivity and refusal to "acknowledge the gravity" of issues he raises.

Professor emeritus of finance and media analyst Edward S. Herman of the University of Pennsylvania, together with independent journalist David Peterson, wrote detailed negative reviews of the book for the International Socialist Review and for The Public Intellectuals Project, concluding it "is a terrible book, both as a technical work of scholarship and as a moral tract and guide. But it is extremely well-attuned to the demands of U.S. and Western elites at the start of the 21st century." Herman and Peterson take issue with Pinker's idea of a 'Long Peace' since World War Two: "Pinker contends not only that the 'democracies avoid disputes with each other', but that they 'tend to stay out of disputes across the board...' This will surely come as a surprise to the many victims of US assassinations, sanctions, subversions, bombings, and invasions since 1945."

Elizabeth Kolbert wrote a critical review in The New Yorker, to which Pinker posted a reply. Kolbert states that "The scope of Pinker's attentions is almost entirely confined to Western Europe." Pinker replies that his book has sections on "Violence Around the World", "Violence in These United States", and the history of war in the Ottoman Empire, Russia, Japan, and China. Kolbert states that "Pinker is virtually silent about Europe's bloody colonial adventures." Pinker replies that "a quick search would have turned up more than 25 places in which the book discusses colonial conquests, wars, enslavements, and genocides." Kolbert concludes, "Name a force, a trend, or a 'better angel' that has tended to reduce the threat, and someone else can name a force, a trend, or an 'inner demon' pushing back the other way." Pinker calls this conclusion "the postmodernist sophistry that The New Yorker so often indulges when reporting on science."

Ben Laws argues on CTheory that "if we take a 'perspectivist' stance in relation to matters of truth would it not be possible to argue the direct inverse of Pinker's historical narrative of violence? Have we in fact become even more violent over time? Each interpretation could invest a certain stake in 'truth' as something fixed and valid – and yet, each view could be considered misguided." Pinker argues in his FAQ page that economic inequality, like other forms of "metaphorical" violence, "may be deplorable, but to lump it together with rape and genocide is to confuse moralization with understanding. Ditto for underpaying workers, undermining cultural traditions, polluting the ecosystem, and other practices that moralists want to stigmatize by metaphorically extending the term violence to them. It's not that these aren't bad things, but you can't write a coherent book on the topic of 'bad things'.... physical violence is a big enough topic for one book (as the length of Better Angels makes clear). Just as a book on cancer needn't have a chapter on metaphorical cancer, a coherent book on violence can't lump together genocide with catty remarks as if they were a single phenomenon." Quoting this, Laws argues that Pinker suffers from "a reductive vision of what it means to be violent."

John Arquilla of the Naval Postgraduate School criticized the book in Foreign Policy for using statistics that he said did not accurately represent the threats of civilians dying in war:

The problem with the conclusions reached in these studies is their reliance on "battle death" statistics. The pattern of the past century – one recurring in history – is that the deaths of noncombatants due to war has risen, steadily and very dramatically. In World War I, perhaps only 10 percent of the 10 million-plus who died were civilians. The number of noncombatant deaths jumped to as much as 50 percent of the 50 million-plus lives lost in World War II, and the sad toll has kept on rising ever since".

Stephen Corry, director of the charity Survival International, criticized the book from the perspective of indigenous people's rights. He asserts that Pinker's book "promotes a fictitious, colonialist image of a backward 'Brutal Savage', which pushes the debate on tribal peoples' rights back over a century and [which] is still used to justify their destruction."

Anthropologist Rahul Oka has suggested that the apparent reduction in violence is just a scaling issue. Wars can be expected to kill larger percentages of smaller populations. As the population grows, fewer warriors are needed, proportionally.

Sinisa Malesevic has argued that Pinker and other similar theorists, such as Azar Gat, articulate a false vision of human beings as being genetically predisposed to violence. He states that Pinker conflates organised and interpersonal violence and cannot explain the proliferation of war, genocides, revolutions and terrorism in modernity. Malesevic argues that organised violence has been on the rise since the formation of the first states (10,000–12,000 years ago) and this process has accelerated with the increased organisational capacity, greater ideological penetration and ability of social organisations to penetrate the networks of micro-solidarity.

A 2016 study in Nature found that lethal violence caused 2% of human deaths around the time of human origin, an estimated six times higher than the rate of mammal death around the time of mammal origin, and rose higher at times (such as the Iron Age) before falling to less than 2% in modern times. Douglas P. Fry of the University of Alabama at Birmingham stated that "recent assertions by Steven Pinker and others that violent death in the Paleolithic was shockingly high are greatly exaggerated. On the contrary, the findings show that social organization is critically important in affecting human violence." Pinker stated the Nature study confirms his book's claims that humans have a natural tendency to engage in lethal violence, that lethal violence was more common in chiefdoms than in prehistoric hunter-gatherer bands, and is less common in modern society.

In March 2018, the academic journal Historical Reflections published the first issue of their 44th volume entirely devoted to responding to Pinker's book in light of its significant influence on the wider culture, such as its appraisal by Bill Gates. The issue contains essays by twelve historians on Pinker's thesis, and the editors of the issue Mark S. Micale, Professor of History at the University of Illinois, and Philip Dwyer, Professor of History at Newcastle University write in the introductory paper that

Not all of the scholars included in this journal agree on everything, but the overall verdict is that Pinker's thesis, for all the stimulus it may have given to discussions around violence, is seriously, if not fatally, flawed. The problems that come up time and again are: the failure to genuinely engage with historical methodologies; the unquestioning use of dubious sources; the tendency to exaggerate the violence of the past in order to contrast it with the supposed peacefulness of the modern era; the creation of a number of straw men, which Pinker then goes on to debunk; and its extraordinarily Western-centric, not to say Whiggish, view of the world.

David Graeber found Pinker's claims to be founded on false accusations of false-dilemma thinking, and also argued that Pinker, through these very accusations, was culpable of false-dilemma assumptions himself. In particular, Graeber criticized Pinker's simultaneous claims that strivings towards utopia would cause violence while Pinker's fear of things getting worse would not. To Graeber, the latter belief's believability lay strongly in its absence of overt utopianism: Pinker merely did not say that the systems he endorsed were perfect. Graeber wrote that Pinker failed to note that the historic political systems which Pinker rejected did not overtly promise utopia in the first place as well. Pinker, to Graeber, dogmatically presupposed a single linear scale, and thereby charged any contrarians thereof of rejecting all linear scales and adopting "black and white thinking". Pinker thereby purportedly constructed a false dilemma between false-dilemma-fraught utopianism, and Pinker's own endorsements.

Awards and honors

- 2011 New York Times Notable Books of 2011

- 2012 Samuel Johnson Prize, shortlist

- 2012 Royal Society Winton Prize for Science Books, shortlist

- 2012–2013 Gifford Lectures at the University of Edinburgh

- 2015 Mark Zuckerberg book club selection, January