Abortion-rights movements, also self-styled as pro-choice movements, advocate for the right to have legal access to induced abortion services including elective abortion. They seek to represent and support women who wish to terminate their pregnancy without fear of legal or social backlash. These movements are in direct opposition to anti-abortion movements.

The issue of induced abortion remains divisive in public life, with recurring arguments to liberalize or to restrict access to legal abortion services. Some abortion-rights supporters are divided as to the types of abortion services that should be available under different circumstances, including periods in the pregnancy such as late term abortions, in which access may or may not be restricted.

Terminology

Many of the terms used in the debate are political framing terms used to validate one's own stance while invalidating the opposition's. For example, the labels pro-choice and pro-life imply endorsement of widely held values such as liberty and freedom, while suggesting that the opposition must be "anti-choice" or "anti-life".

These views do not always fall along a binary; in one Public Religion Research Institute poll, they noted that the vagueness of the terms led to seven in ten Americans describing themselves as "pro-choice", while almost two-thirds described themselves as "pro-life". It was found that, in polling, respondents would label themselves differently when given specific details about the circumstances around an abortion including factors such as rape, incest, viability of the fetus, and survivability of the mother.

The Associated Press favors the terms "abortion rights" and "anti-abortion" instead.

History

Abortion practices date back to 1550 BCE, based on the findings of practices recorded on documents. Abortion has been an active practice since Egyptian medicine. Centuries later, abortion was a topic taken up by feminism. According to historian James C. Mohr, there was an earlier acceptance of abortion, and opposition to abortion, including anti-abortion laws, only came into being in the 19th century. It was not always a crime and was generally not illegal until quickening, which occurred between the fourth and sixth month of pregnancy. In the 19th century, the medical profession was generally opposed to abortion, which Mohr argues it arose due to competition between men with medical degrees and women without one, such as Madame Drunette. The practice of abortion was one of the first medical specialities, and was practiced by unlicensed people; well-off people had abortions and paid well. The press played a key role in rallying support for anti-abortion laws.

The ideas of the legalization of abortion in the late 19th century were often opposed by feminists, seeing it as a means of relieving men of responsibility. In The Revolution, which was an official published newspaper of women's rights that went out weekly, operated by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, an anonymous contributor signing "A" wrote in 1869 about the subject, arguing that instead of merely attempting to pass a law against abortion, the root cause must also be addressed. The Revolution newspaper highly impacted the women's rights movement, and for the first time, it seemed like women's voices were being heard through the proclamations of these unacknowledged subjects regarding women and their everyday rights and safety as citizens. The writer wrote that simply passing an anti-abortion law would "be only mowing off the top of the noxious weed, while the root remains. ... No matter what the motive, love of ease, or a desire to save from suffering the unborn innocent, the woman is awfully guilty who commits the deed. It will burden her conscience in life, it will burden her soul in death; But oh! thrice guilty is he who drove her to the desperation which impelled her to the crime."

Between 1900 and 1965, there were not any anti-abortion movements or rallies because states had already passed a law banning abortions at all levels, including prescriptions and procedures. The only exception for a woman to get an abortion without fear of legal retribution was if a licensed physician determined the abortion would protect the mother's life. Physicians who provide abortions and women who have abortions were constantly harassed by courts and prosecutors. In the 1960s, some states began to request changes with the abortion law. In 1959, a group of experts set up a model enactment that supported the advancement of the abortion laws. These experts suggested that the abortion laws should provide exemptions for women that were sexually assaulted or for a baby that may not have a good quality of life. The abortion-rights movement became a controversial topic in the United States regarding abortion and reproduction.

United Kingdom

The movement towards the liberalization of abortion law emerged in the 1920s and 1930s in the context of the victories that had been recently won in the area of birth control. Campaigners including Marie Stopes in England and Margaret Sanger in the US had succeeded in bringing the issue into the open, and birth control clinics were established which offered family planning advice and contraceptive methods to women in need. Birth control is a method of pregnancy prevention through controlled contraception.

In 1929, the Infant Life Preservation Act was passed in the United Kingdom, which amended the law (Offences against the Person Act 1861) so that an abortion carried out in good faith, for the sole purpose of preserving the life of the mother, would not be an offense. Many citizens had mixed opinions on this, but ultimately started protesting this as child destruction. Child destruction was known as taking the life of a viable unborn child during a pregnancy or at birth, before it is independent of its mother. If there is an intent of death and no good faith is carried out in the process in order to protect the mother's livelihood, the offense carries a maximum punishment of life imprisonment. The Infant Life Preservation Act defines the difference between murder and abortion-the causing of a miscarriage.

Stella Browne was a leading birth control campaigner, who increasingly began to venture into the more contentious issue of abortion in the 1930s. Browne's beliefs were heavily influenced by the work of Havelock Ellis, Edward Carpenter and other sexologists. She came to strongly believe that working women should have the choice to become pregnant and to terminate their pregnancy while they worked in the horrible circumstances surrounding a pregnant woman who was still required to do hard labor during her pregnancy. In this case she argued that doctors should give free information about birth control to women that wanted to know about it. This would give women agency over their own circumstances and allow them to decide whether they wanted to be mothers or not.

In the late 1920s, Browne began a speaking tour around England, providing information about her beliefs on the need for accessibility of information about birth control for women, women's health problems, problems related to puberty and sex education and high maternal morbidity rates among other topics. These talks urged women to take matters of their sexuality and their health into their own hands. She became increasingly interested in her view of the woman's right to terminate their pregnancies, and in 1929, she brought forward her lecture "The Right to Abortion" in front of the World Sexual Reform Congress in London. In 1931, Browne began to develop her argument for women's right to decide to have an abortion. She again began touring, giving lectures on abortion and the negative consequences that followed if women were unable to terminate pregnancies of their own choosing such as: suicide, injury, permanent invalidism, madness and blood-poisoning.

Other prominent feminists, including Frida Laski, Dora Russell, Joan Malleson and Janet Chance began to champion this cause – the cause broke dramatically into the mainstream in July 1932 when the British Medical Association council formed a committee to discuss making changes to the laws on abortion. On February 17, 1936, Janet Chance, Alice Jenkins and Joan Malleson established the Abortion Law Reform Association as the first advocacy organization for abortion liberalization. The association promoted access to abortion in the United Kingdom and campaigned for the elimination of legal obstacles. In its first year ALRA recruited 35 members, and by 1939 had almost 400 members.

The ALRA was very active between 1936 and 1939 sending speakers around the country to talk about Labour and Equal Citizenship and attempted, though most often unsuccessfully, to have letters and articles published in newspapers. They became the most popular when a member of the ALRA's Medico-Legal Committee received the case of a fourteen-year-old girl who had been raped, and received a termination of this pregnancy from Dr. Joan Malleson, a progenitor of the ALRA.

In 1938, Joan Malleson precipitated one of the most influential cases in British abortion law when she referred a pregnant fourteen-year old rape survivor to gynaecologist Aleck Bourne. He performed an abortion, then illegal, and was put on trial on charges of procuring abortion. Bourne was eventually acquitted in R v. Bourneas his actions were "...an example of disinterested conduct in consonance with the highest traditions of the profession". This court case set a precedent that doctors could not be prosecuted for performing an abortion in cases where pregnancy would probably cause "mental and physical wreck".

The Abortion Law Reform Association continued its campaigning after the Second World War, and this, combined with broad social changes brought the issue of abortion back into the political arena in the 1960s. President of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists John Peel chaired the committee advising the British Government on what became the Abortion Act 1967, which allowed for legal abortion on a number of grounds, including to avoid injury to the physical or mental health of the woman or her existing child(ren) if the pregnancy was still under 28 weeks.

United States

In America an abortion reform movement emerged in the 1960s. In 1964, Gerri Santoro of Connecticut died trying to obtain an illegal abortion and her photo became the symbol of the abortion rights movement. Some women's rights activist groups developed their own skills to provide abortions to women who could not obtain them elsewhere. As an example, in Chicago, a group known as "Jane" operated a floating abortion clinic throughout much of the 1960s. Women seeking the procedure would call a designated number and be given instructions on how to find "Jane".

In the late 1960s, a number of organizations were formed to mobilize opinion both against and for the legalization of abortion. The forerunner of the NARAL Pro-Choice America was formed in 1969 to oppose restrictions on abortion and expand access to abortion. In late 1973, NARAL became the National Abortion Rights Action League.

The landmark judicial ruling of the Supreme Court in Roe v. Wade ruled that a Texas statute forbidding abortion except when necessary to save the life of the mother was unconstitutional. This was back in 1970, where Jane Roe, (which was actually a fictional name used in the court documents in order to protect the plaintiff's identity), had filed a lawsuit against Henry Wade. He was the district attorney of Dallas County in Texas, where Jane Roe resided. She was challenging a Texas law making abortion illegal except by a doctor's orders to save a woman's life. The Court arrived at its decision by concluding that the issue of abortion and abortion rights falls under the right to privacy. The Court held that a right to privacy existed and included the right to have an abortion. The court found that a mother had a right to abortion until viability, a point to be determined by the abortion doctor. After viability a woman can obtain an abortion for health reasons, which the Court defined broadly to include psychological well-being in the decision Doe v. Bolton, delivered concurrently.

From the 1970s, and the spread of second-wave feminism, abortion and reproductive rights became unifying issues among various women's rights groups in Canada, the United States, the Netherlands, Britain, Norway, France, Germany, and Italy.

In 2015, in the wake of the House of Representatives' vote to defund Planned Parenthood, Lindy West, Amelia Bonow and Kimberly Morrison launched ShoutYourAbortion to "remind supporters and critics alike abortion is a legal right to anyone who wants or needs it". The women encouraged other women to share positive abortion experiences online using the hashtag #ShoutYourAbortion in order to "denounce the stigma surrounding abortion."

In 2019, the You Know Me movement started as a response to the successful 2019 passage of fetal heartbeat bills in five states in the United States, most notably the passing of anti-abortion laws in Georgia (House Bill 381), Ohio (House Bill 68) and Alabama (House Bill 314). This movement was started off by actress Busy Philipps because she had previously had an abortion when she was a teen. The actress and many others believe that it is important for women to speak up and shift the narrative, especially because abortion is such a taboo subject.

In the mid-19th century, concerns around abortion only consisted of the danger of a woman being poisoned and risking her health, not because of religion, ethics, or diplomacy. Ending a pregnancy before the fetus began movement, or "post-quickening" was only a wrongdoing, not a crime. The laws that were against abortions post-quickening removals were put in place to protect the well-being of the women that were pregnant, not the fetal life. It was more common for women to die during early terminations due to the usage of pre-owned instruments as opposed to natural abortifacients. Some women who engaged in quickening abortions were not prosecuted because there was no evidence and quickening was hard to prove.

Between 1900 and 1965, there were not any anti-abortion movements or rallies because states had already passed a law banning abortions at all levels included the prescription of drugs or undergoing procedures. The only exception for a woman to proceed with an abortion without worrying about breaking any anti-abortion laws is if a licensed physician were to prove that the abortion was for the protection of the mother's life. Abortion care providers and women who had obtained an abortion were pestered by courts and prosecutors.

In the 1960s, some states began to request changes, around the abortion law, from their states. In 1959, a group of experts set up a model enactment that supported the advancement of the fetus removal laws that were put in place. These experts suggested that the abortion laws should exempt women that were sexually assaulted, whose babies well-being were to be questioned and whose babies that were to be born out of its true, natural or original state. The Abortion Rights Movement became a cultural shift in The United States about the intentions of reproduction and abortion.

In 1973, the Roe v. Wade verdict changed the abortion laws altogether, making abortion legal. Many physicians and healthcare professionals jeopardized their medical licenses, risked being put in prison and fined by the state because they wanted to continue to provide abortions.

There were more than 1,000 abortion laws passed and enacted between 2011 and 2019 that limited access to abortion procedures. Some of these laws forbid a woman getting an abortion past a certain gestational age and was also based on race and specific pregnancy conditions. Other laws were established that ban particular abortion methods.

Targeted regulation of abortion providers (TRAP) was put in place to target abortion clinics by demanding unnecessary requirements that made it hard for women to get an abortion. Anti-abortion rights claim that these requirements are for the safety of the mother and child, but that has not been scientifically proven. TRAP has placed limitations on abortion facilities to make it more difficult for them to provide abortion services that will essentially force them to not provide abortion services at all. TRAP policies have been put in place by 26 states as of 2020. During the pandemic, numerous states prohibited non-essential medical procedures, including abortion services. Policymakers in twelve states saw this as a chance to certify abortion as non-essential, therefore ending services.

Around the world

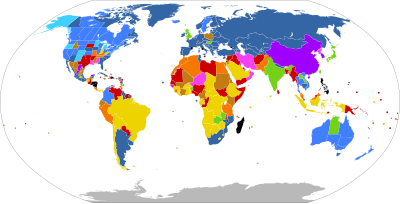

| Legal on request: | |

| No gestational limit | |

| Gestational limit after the first 17 weeks | |

| Gestational limit in the first 17 weeks | |

| Unclear gestational limit | |

| Legally restricted to cases of: | |

| Risk to woman's life, to her health*, rape*, fetal impairment*, or socioeconomic factors | |

| Risk to woman's life, to her health*, rape, or fetal impairment | |

| Risk to woman's life, to her health*, or fetal impairment | |

| Risk to woman's life*, to her health*, or rape | |

| Risk to woman's life or to her health | |

| Risk to woman's life | |

| Illegal with no exceptions | |

| No information | |

| * Does not apply to some countries or territories in that category | |

Africa

South Africa allows abortion on demand under its Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act. Most African nations, however, have abortion bans except in cases where the woman's life or health is at risk. A number of abortion-rights international organizations have made altering abortion laws and expanding family planning services in sub-Saharan Africa and the developing world a top priority.

To classify the reasons as to which abortion should be legally permitted, countries in Africa fall within six categories: abortion is not permitted at all, abortion is only allowed to save the life of a woman, abortion can be performed if a woman's physical health is at risk, to save the mental health of a woman, to save or preserve socioeconomic reasons and abortions are allowed without any restrictions. But there are only five countries in Africa where abortion is legal and those countries are Cape Verde, South Africa, Tunisia, Mozambique and Saõ Tome & Principe.

During 2010–2014. 8.2 million abortions were performed each year in Africa. This number increased drastically compared to the 4.6 million abortions that were performed during 1990–1994. But this increased number of abortions is due to the increase of women that are reproducing at a young age. Approximately 93% of women within their reproductive age live in countries that have very restrictive abortion laws and abortion is only legal in 10 out of 54 African countries, leading to fewer women not being able to obtain a safe procedure. The World Health Organization only recommends trained personnel when performing induced abortions but not many women in Africa have access to trained professionals who are able to provide them with the best service to decrease the number of complications due to abortion. Approximately 1.6 million women are treated for abortion-related complications and only one in four abortions in Africa are safe. Africa has the highest number of deaths that are related to abortion and this is due to the most common complication of abortion that consist of excessive blood loss and an incomplete abortion that can lead to an infection.

Asia

During 2010–2014, 36 million abortions were performed in Asia. Majority of abortions occurred in Central and South Asia at a rate of 16 million in India and Asia and 13 million in China alone.

Although the abortions performed in Asia are not known, there is an estimated 4.6 million women who are treated because they have complications due to the performance of an unsafe abortion. The major complication of abortion is an incomplete abortion where a woman can experience an immoderate amount of blood loss and can develop an infection. Less common complications of abortion include a woman going into septic shock, damaging the internal organs and causing the peritoneum to be inflamed, all due to the unclean and unsterilized instruments that are being used doing the procedure. Untreated complications from abortions can leave women to experience negative health consequences for life that include infertility, chronic pain, inflammation of the reproductive organs and pelvic inflammatory disease. Unsafe abortions go deeper than just a woman's health but they lead to reduced productivity for women increased costs to an already struggling family. Although it is not completely known, a drug known as misoprostol is used to perform abortions in Asian countries and evidence shows that the sales of this drug has increased in Asia over the course of years.

On record, out of all the pregnancies in Asia, 27 percent of them end in abortions. This is the reason for the Asia Safe Abortion Partnership (ASAP). This program was formed to increase the accessibility to safe and legal abortions and health care that is needed after any abortion service. 50 countries occupy Asia and out of those 50, 17 countries do not have a restriction on abortions excluding, gestational limits and permission from a spouse or parent. ASAP satisfies the demand for safe and accessible abortions through educational and advocacy. By grouping with other countries to promote advocacy networks, ASAP has created a worldwide and generational feminist power that advocates for women's abortion rights, autonomy and dignity. Anti-abortion groups have tried their best to discriminate the reproductive autonomy of women but ASAP has members spread across 20 countries that promote the women's movement for abortion rights, laws, and access.

Even though abortion is legal in Asia, that does not mean that women always have access or adequate health care during these times. For example, abortions in India have been legal since 1951 but women who are particularly poor or marginalized make up 50% of unsafe abortions. Women in the Philippines are more than likely to undergo an unsafe and unsanitary abortion causing around 1,000 death annually due to abortion complications. The Philippines along with Iraq and Laos are the countries that has not made abortion legal, excluding legal exceptions, therefore they have not made it available to where women can have admissions to legal abortions that are safe for them and their bodies. Countries such as Afghanistan, Thailand, China and Lebanon, have all been impacted by the determined long-term feminist motion by ASAP for women's abortion rights.

This work ranges from workshops, journalist, advocates to menstrual management, violence against women, and issues surrounded around unplanned pregnancies. "Youth champions" were created by ASAP to share the knowledge that they have learned to their peers about sexual activity, abortions, women's rights and reproductions, reproductive health, and the abortion rights movement in general. Youth champions have been trained directly by members of ASAP and have been very successful in their training that include issues around disability rights that can widen the interrelation research of the women's forces to help assimilate reproductive and sexual rights within the human rights movement.

Japan

Chapter XXIX of the Penal Code of Japan makes abortion illegal in Japan. However, the Maternal Health Protection Law allows approved doctors to practice abortion with the consent of the mother and her spouse, if the pregnancy has resulted from rape, or if the continuation of the pregnancy may severely endanger the maternal health because of physical reasons or economic reasons. Other people, including the mother herself, trying to abort the fetus can be punished by the law. People trying to practice abortion without the consent of the woman can also be punished, including the doctors.

South Korea

Abortion has been illegal in South Korea since 1953 but on April 11, 2019, South Korea's Constitutional Court ruled the abortion ban unconstitutional and called for the law to be amended. The law stands until the end of 2020. The Constitutional Court has taken into consideration abortion-rights cases by women because they find the abortion ban as unconstitutional. To help support the legalization of abortion in South Korea, thousands of advocates compiled a petition for the Blue House to consider lifting the ban. Due to the abortion ban, this has led to many dangerous self-induced abortions and other illegal practices of abortion that needs more attention. This is why there are advocates challenging the law to put into perspective the negative factors this abortion ban brings. By making abortion illegal in South Korea, this also creates an issue when it comes to women's rights and their own rights to their bodies. As a result, many women's advocate groups were created and acted together to protest against the abortion ban law.

Global Day of Action is a form of protest that advocates to make a change and bring more awareness to global warming. During this protest, a group of feminist Korean advocates called, "The Joint Action for Reproductive Justice" connected with one another to promote concerns that requires more attention and needs a quick change such as making abortion legal. By combining different advocate groups that serves different purposes and their own goals they want to achieve into one event, it helps promote all the different aspects of reality that needs to change.

Abortion-rights Advocate Groups:

- Center for Health and Social Change

- Femidangdang

- Femimonsters

- Flaming Feminist Action

- Korea Sexual Violence Relief Center

- Korean Women's Associations United

- Korea Women's Hot Line

- Network for Glocal Activism

- Sexual and Reproductive Rights Forum

- Womenlink

- Women with Disabilities Empathy

Russia

In 1920, under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin, Russia became the first country in the world to legally permit abortion, no matter the circumstances.

But in the 20th century, the laws surrounding abortion were repeatedly modified between the years of 1936 and 1955. According to data from the United Nations in 2010, Russia had the highest rates of abortion per woman of reproduction. Results from the abortion rates of China and Russia were compared and out of a population of 1.3 billion people, China only reported 13 million abortions, a huge difference when contrasted to the population in Russia of 143 million people with 1.2 million abortions. Since abortion was illegal in the Russian Empire, it was not recognized in the Domostroi. The Domostroi was a set of tasks that were to be followed that were structured around rules, instructions surrounded by religious, social and domestic issues that were centered within the Russian Society. These rules enforced respect and compliance to God and the church.

Different rulers had different views about abortion. During Romanov's reign, abortion was illegal, frowned up, and if a woman were to go through with an abortion, her punishment was death. But after Romanov's reign ended, Peter the Great lifted the punishment of death for abortions but it was still considered a serious issue in 1917. Before the punishment for abortions was death, according to the Russian Penal Code that dates back to 1462–1463, women were dispossessed of their basic human and civil rights and banned from the city or they were forced into hard labor.

These harsh treatments and illegality surrounded around abortion still did not stop women from pursuing abortions. "Black Market" abortions were known as unauthorized and discreet procedures done by women who have experience in childbirth. These women were known as older women that were midwives and rural midwives, respectfully. Although these women were not abortion care providers, they were the only accessible obstetric personnel that women could go to without facing the harsh punishment and consequences forced upon by the Russian Society. Since adequate medical care was not provided for women looking to terminate their pregnancy, midwives and nurses from villages were trained to care for these women the best to their ability, but of course with illegal abortions there are always repercussions.

During the Soviet period in Russia, abortions ranked as the highest rates world-wide. After the Soviet period ended inn the Russian union, abortion numbers decreased with further enforced sex education courses and use of contraceptive birth control.

Europe

Ireland

Republic of Ireland

Abortion was illegal in the Republic of Ireland except when the woman's life was threatened by a medical condition (including risk of suicide), since a 1983 referendum (aka 8th Amendment) amended the constitution. Subsequent amendments in 1992 (after the X Case) – the thirteenth and fourteenth – guaranteed the right to travel abroad (for abortions) and to distribute and obtain information of "lawful services" available in other countries. Two proposals to remove suicide risk as a ground for abortion were rejected by the people, in a referendum in 1992 and in 2002. Thousands of women get around the ban by privately traveling to the other European countries (typically Britain and the Netherlands) to undergo termination, or by ordering abortion pills from Women on Web online and taking them in Ireland.

Sinn Féin, the Labour Party, Social Democrats, Green Party, Communist Party, Socialist Party and Irish Republican Socialist Party have made their official policies to support abortion rights. Mainstream center-right parties such as Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael do not have official policies on abortion rights but allow their members to take a conscience vote in support of abortion in limited circumstances. Aontú, founded in January 2019, is firmly anti-abortionist and seeks to "protect the right to life".

After the death of Savita Halappanavar in 2012, there has been a renewed campaign to repeal the eighth amendment and legalize abortion. As of January 2017, the Irish government has set up a citizens assembly to look at the issue. Their proposals, broadly supported by a cross-party Oireachtas committee, include repeal of the 8th Amendment, unrestricted access to abortion for the first 12 weeks of pregnancy and no-term limits for special cases of fatal foetal abnormalities, rape and incest.

A referendum on the repealing of the 8th Amendment was held on May 25, 2018. Together for Yes, a cross-society group formed from the Coalition to Repeal the 8th Amendment, the National Women's Council of Ireland and the Abortion Rights Campaign, were the official campaign group for repeal in the referendum. Activists utilized social media to bring the narrative of women's voices to the forefront of the campaign, making clear that the Eighth Amendment was dangerous for pregnant women to try and encourage voters to vote in favor of repeal. The 67% majority in favor of repeal is a testament to these stories and the women who braved the public Twitter sphere to change the law around women's reproductive lives.

Northern Ireland

Despite being part of the United Kingdom, abortion remained illegal in Northern Ireland, except in cases when the woman is threatened by a medical condition, physical or mental, until 2019. Women seeking abortions had to travel to England. In October 2019, abortion up to 12 weeks was legalized, to begin in April 2020, but remains near-unobtainable.

Poland

Poland initially held abortion to be legal in 1958 by the communist government, but was later banned after restoration of democracy in 1989.

Currently, abortion is illegal in all cases except for rape or when the fetus or mother is in fatal conditions. The wide spread of Catholic Church in Poland within the country has made abortion socially 'unacceptable'. The Pope has had major influence on the acceptance of abortion within Poland. Several landmark court cases have had substantial influence on the current status of abortion, including Tysiac v Poland.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, the Abortion Act 1967 legalized abortion on a wide number of grounds, except in Northern Ireland. In Great Britain, the law states that pregnancy may be terminated up to 24 weeks if it:

- puts the life of the pregnant woman at risk

- poses a risk to the mental and physical health of the pregnant woman

- poses a risk to the mental and physical health of the fetus

- shows there is evidence of extreme fetal abnormality i.e. the child would be seriously physically or mentally handicapped after birth and during life.

However, the criterion of risk to mental and physical health is applied broadly, and de facto makes abortion available on demand, though this still requires the consent of two National Health Service doctors. Abortions in Great Britain are provided at no out-of-pocket cost to the patient by the NHS.

The Labour Party and the Liberal Democrats are predominantly pro-abortion-rights parties, though with significant minorities in each either holding more restrictive definitions of the right to choose, or subscribing to an anti-abortion analysis. The Conservative Party is more evenly split between both camps and its former leader, David Cameron, supports abortion on demand in the early stages of pregnancy.

Middle East

Abortion laws in the Middle East reflect variation of opinions. Some countries permit abortion in cases involving a pregnant woman's well-being, fetal impairment, and rape. Abortion was widely practiced during the colonial period, and allowed a longer term termination. By the 19th century, progressive interpretations cut the abortion time limit down to the first trimester. However, a 2008 World Health Organization report estimated 900,000 unsafe abortion occurred each year in the Middle Eastern and Northern Africa regions. While many countries have decriminalized abortions and made it more accessible, there are still a few remaining countries yet to do so.

Iran

Abortion was first legalized in 1978. In April 2005, the Iranian Parliament approved a new bill easing the conditions by also allowing abortion in certain cases when the fetus shows signs of handicap. Legal abortion is now allowed if the mother's life is in danger, and also in cases of fetal abnormalities that makes it not viable after birth (such as anencephaly) or produce difficulties for mother to take care of it after birth, such as major thalassemia or bilateral polycystic kidney disease.

North America

United States

Abortion-rights advocacy in the United States is centered in the United States abortion-rights movement.

South America

Across the world, there are only four countries in which abortion is completely banned. Honduras, Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, and El Salvador have yet to legalize abortions, even if it is for the woman's health and safety. Since 2018, there have been no changes in the laws regarding abortion in these Latin-America countries. The Ministry of Public Health collected data that showed nearly half the pregnancies in the Dominican Republic alone are unwanted or unplanned; often stemming from incest or rape. Women in South America continue fighting for their rights and protection, but there has been no recent call of action.

Argentina

Because Argentina has been very restrictive against abortion, reliable reporting on abortion rates is unavailable. Argentina has long been a strongly Catholic country, and protesters seeking liberalized abortion in 2013 directed anger toward the Catholic Church. Argentina is the home of the anti-violence organization Ni una menos, which was formed in 2015 to protest the murder of Daiana García, which opposes the violation of a woman's right to choose the number and interval of pregnancies.

On December 11, 2020, after a 20-hour debate, the Chamber of Deputies voted 131 to 117 (6 abstentions) to approve a bill legalizing abortion up to 14 weeks after conception. The bill's passing resulted in large-scale celebrations by abortion rights activists who had long campaigned for it. The Argentine Senate approved the bill 38–29 on December 29, and it is expected to be signed by President Alberto Fernandez. Argentina will become the fourth Latin American country to legalize abortion.

Because of the ongoing discrimination that women face around the world, many organizations have come together and will come together to work and make efforts to equalize the rights and respect for women. Women's Autonomic, Equality and Reproductive Health and International Human Rights: Between Recognition, Backlash and Regressive Trends is a group that makes efforts towards the discrimination against women in law. This organization represents and advocates the rights of women to equality, dignity, and respect for her private life without discrimination. They have certain beliefs and outlooks towards humanitarian rights regarding termination of pregnancy at any time during the full pregnancy, and make aware that they believe the right of pregnant women to access termination of pregnancy should be autonomous affordable and effective. The fight for women's right, especially regarding her choice to abortion, has been an ongoing event with many negotiations, arguments, and exception. Overtime, many political figures have tried to contribute to the best of their ability to equalize women's rights, which surfaces the main discriminators of all women who seek out abortion. It is not limited to the political figures, but the women's peers, authorities, family, friends, coworkers, etc. Discrimination is not limited to law, and as this becomes more apparent, it is the goal of this movement, the Abortion Rights Movement, to allow women to choose discreetly what is best fitting for their lifestyle and their needs.