Ocean deoxygenation is the reduction of the oxygen content in different parts of the ocean due to human activities. It occurs firstly in coastal zones where eutrophication has driven some quite rapid (in a few decades) declines in oxygen to very low levels. This type of ocean deoxygenation is also called "dead zones". Secondly, there is now an ongoing reduction in oxygen levels in the open ocean: naturally occurring low oxygen areas (so called oxygen minimum zones (OMZs)) are now expanding slowly. This expansion is happening as a consequence of human caused climate change. The resulting decrease in oxygen content of the oceans poses a threat to marine life, as well as to people who depend on marine life for nutrition or livelihood. Ocean deoxygenation poses implications for ocean productivity, nutrient cycling, carbon cycling, and marine habitats.

Ocean warming exacerbates ocean deoxygenation and further stresses marine organisms, reducing nutrient availability by increasing ocean stratification through density and solubility effects while at the same time increasing metabolic demand. The rising temperatures in the oceans cause a reduced solubility of oxygen in the water, which can explain about 50% of oxygen loss in the upper level of the ocean (>1000 m). Warmer ocean water holds less oxygen and is more buoyant than cooler water. This leads to reduced mixing of oxygenated water near the surface with deeper water, which naturally contains less oxygen. Warmer water also raises oxygen demand from living organisms; as a result, less oxygen is available for marine life.

Studies have shown that oceans have already lost 1-2% of their oxygen since the middle of the 20th century, and model simulations predict a decline of up to 7% in the global ocean O2 content over the next hundred years. The decline of oxygen is projected to continue for a thousand years or more.

Terminology

The term ocean deoxygenation has been used increasingly by international scientific bodies because it captures the decreasing trend of the world ocean's oxygen inventory. Oceanographers and others have discussed what phrase best describes the phenomenon to non-specialists. Among the options considered have been ocean suffocation, ocean oxygen deprivation, decline in ocean oxygen, marine deoxygenation, ocean oxygen depletion and ocean hypoxia.

Types and mechanisms

There are two types of ocean deoxygenation, taking place in two different zones and having different causes: the reduction of oxygen in coastal zones versus in the open ocean as well as deep ocean (oxygen minimum zones). These are coupled but different.

Coastal zones

Open and deep ocean zones (oxygen minimum zones)

In the open ocean there are natural low oxygen areas and these are expanding slowly. These oceanic oxygen minimum zones (OMZ) generally occur in the middle depths of the ocean, from 100 – 1000 m deep. They are natural phenomena that result from respiration of sinking organic material produced in the surface ocean. However, as the oxygen content of the ocean decreases, oxygen minimum zones are expanding both vertically and horizontally. In these low oxygen areas the water circulation is slow. This stability means it is easier to see quite small changes in oxygen, such as a decline of 1-2%. In many of these areas, this decline does not mean these low oxygen regions become uninhabitable for fish and other marine life but over many decades may do, particularly in the Pacific and Indian Ocean.

Oxygen is input into the ocean at the surface, through the processes of photosynthesis by phytoplankton and mixing with the atmosphere. Organisms, both microbial and multicellular, use oxygen in respiration throughout the entire depth of the ocean, so when the supply of oxygen from the surface is less than the utilization of oxygen in deep water, oxygen loss occurs.

This phenomenon is natural, but is exacerbated with increased stratification and increasing ocean temperature. Stratification occurs when water masses with different properties, primarily temperature and salinity, are layered, with lower density water on top of higher density water. The larger the differences in the properties between layers, the less mixing occurs between the layers. Stratification is increased when the temperature of the surface ocean or the amount of freshwater input into the ocean from rivers and ice melt increases, enhancing ocean deoxygenation by reducing supply. Another factor that can reduce supply is the solubility of oxygen. As temperature and salinity increase, the solubility of oxygen decreases, meaning that less oxygen can be dissolved into water as it warms and becomes more salty.

Role of climate change

While oxygen minimum zones (OMZs) occur naturally, they can be exacerbated by human impacts like climate change and land-based pollution from agriculture and sewage. The prediction of current climate models and climate change scenarios is that substantial warming and loss of oxygen throughout the majority of the upper ocean will occur. Global warming increases ocean temperatures, especially in shallow coastal areas. When the water temperature increases, its ability to hold oxygen decreases, leading to oxygen concentrations going down in the water. This compounds the effects of eutrophication in coastal zones described above.

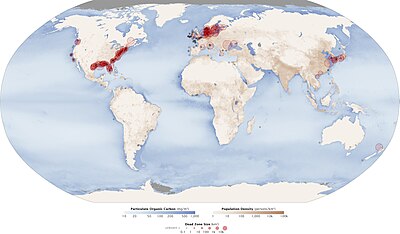

Open ocean areas with no oxygen have grown more than 1.7 million square miles in the last 50 years, and coastal waters have seen a tenfold increase in low-oxygen areas in the same time.

Measurement of dissolved oxygen in coastal and open ocean waters for the past 50 years has revealed a marked decline in oxygen content. This decline is associated with expanding spatial extent, expanding vertical extent, and prolonged duration of oxygen-poor conditions in all regions of the global oceans. Examinations of the spatial extent of OMZs in the past through paleoceanographical methods clearly shows that the spatial extent of OMZs has expanded through time, and this expansion is coupled to ocean warming and reduced ventilation of thermocline waters.

Research has attempted to model potential changes to OMZs as a result of rising global temperatures and human impact. This is challenging due to the many factors that could contribute to changes in OMZs. The factors used for modeling change in OMZs are numerous, and in some cases hard to measure or quantify. Some of the processes being studied are changes in oxygen gas solubility as a result of rising ocean temperatures, as well as changes in the amount of respiration and photosynthesis occurring around OMZs. Many studies have concluded that OMZs are expanding in multiple locations, but fluctuations of modern OMZs are still not fully understood. Existing Earth system models project considerable reductions in oxygen and other physical-chemical variables in the ocean due to climate change, with potential ramifications for ecosystems and humans.

The global decrease in oceanic oxygen content is statistically significant and emerging beyond the envelope of natural fluctuations. This trend of oxygen loss is accelerating, with widespread and obvious losses occurring after the 1980s. The rate and total content of oxygen loss varies by region, with the North Pacific emerging as a particular hotspot of deoxygenation due to the increased amount of time since its deep waters were last ventilated (see thermohaline circulation) and related high apparent oxygen utilization (AOU). Estimates of total oxygen loss in the global ocean range from 119 to 680 T mol decade−1 since the 1950s. These estimates represent 2% of the global ocean oxygen inventory.

Melting of gas hydrates in bottom layers of water may result in the release of more methane from sediments and subsequent consumption of oxygen by aerobic respiration of methane to carbon dioxide. Another effect of climate change on oceans that causes ocean deoxygenation is circulation changes. As the ocean warms from the surface, stratification is expected to increase, which shows a tendency for slowing down ocean circulation, which then increases ocean deoxygenation.

Estimates for the future

The results from mathematical models show that global ocean oxygen loss rates will continue to accelerate up to 125 T mol year−1 by 2100 due to persistent warming, a reduction in ventilation of deeper waters, increased biological oxygen demand, and the associated expansion of OMZs into shallower areas.

Variations

Expanding oxygen minimum zones (OMZ)

Several areas of the open ocean have naturally low oxygen concentration due to biological oxygen consumption that cannot be supported by the rate of oxygen input to the area from physical transport, air-sea mixing, or photosynthesis. These areas are called oxygen minimum zones (OMZs), and there is a wide variety of open ocean systems that experience these naturally low oxygen conditions, such as upwelling zones, deep basins of enclosed seas, and the cores of some mode-water eddies.

Ocean deoxygenation has led to suboxic, hypoxic, and anoxic conditions in both coastal waters and the open ocean. Since 1950, more than 500 sites in coastal waters have reported oxygen concentrations below 2 mg liter−1, which is generally accepted as the threshold of hypoxic conditions.

The extent of OMZs has expanded in tropical oceans during the past half century.

Oxygen-poor waters of coastal and open ocean systems have largely been studied in isolation of each other, with researchers focusing on eutrophication-induced hypoxia in coastal waters and naturally occurring (without apparent direct input of anthropogenic nutrients) open ocean OMZs. However, coastal and open ocean oxygen-poor waters are highly interconnected and therefore both have seen an increase in the intensity, spatial extent, and temporal extent of deoxygenated conditions.

The spatial extent of deoxygenated conditions can vary widely. In coastal waters, regions with deoxygenated conditions can extend from less than one to many thousands of square kilometers. Open ocean OMZs exist in all ocean basins and have similar variation in spatial extent; an estimated 8% of global ocean volume is within OMZs. The largest OMZ is in the eastern tropical north Pacific and comprises 41% of this global volume, and the smallest OMZ is found in the eastern tropical North Atlantic and makes up only 5% of the global OMZ volume.

Vertical extent of low oxygen conditions

The vertical extent of low oxygen conditions is also variable, and areas of persistent low oxygen have annual variation in the upper and lower limits of oxygen-poor waters. Typically, OMZs are expected to occur at depths of about 200 to 1,000 meters. The upper limit of OMZs is characterized by a strong and rapid gradient in oxygenation, called the oxycline. The depth of the oxycline varies between OMZs, and is mainly affected by physical processes such as air-sea fluxes and vertical movement in the thermocline depth. The lower limit of OMZs is associated with the reduction in biological oxygen consumption, as the majority of organic matter is consumed and respired in the top 1,000 m of the vertical water column. Shallower coastal systems may see oxygen-poor waters extend to bottom waters, leading to negative effects on benthic communities.

Many persistent OMZs have increased in thickness over the last five decades. This happened because the upper limit of the OMZ became shallower and also because the OMZ expanded downward.

Variations in temporal duration

The temporal duration of oxygen-poor conditions can vary on seasonal, annual, or multi-decadal scales. Hypoxic conditions in coastal systems like the Gulf of Mexico are usually tied to discharges of rivers, thermohaline stratification of the water column, wind-driven forcing, and continental shelf circulation patterns. As such, there are seasonal and annual patterns in the initiation, persistence, and break down of intensely hypoxic conditions. Oxygen concentrations in open oceans and the margins between coastal areas and the open ocean may see variation in intensity, spatial extent, and temporal extent from multi-decadal oscillations in climatic conditions.

Coastal regions have also seen expanded spatial extent and temporal duration due to increased anthropogenic nutrient input and changes in regional circulation. Areas that have not previously experienced low oxygen conditions, like the coastal shelf of Oregon on the West coast of the United States, have recently and abruptly developed seasonal hypoxia.

Impacts

Ocean deoxygenation poses implications for ocean productivity, nutrient cycling, carbon cycling, and marine habitats. Studies have shown that oceans have already lost 1-2% of their oxygen since the middle of the 20th century, and model simulations predict a decline of up to 7% in the global ocean O2 content over the next hundred years. The decline of oxygen is projected to continue for a thousand years or more.

The viability of species is being disrupted throughout the ocean food web due to changes in ocean chemistry. As the ocean warms, mixing between water layers decreases, resulting in less oxygen and nutrients being available for marine life.

Ocean deoxygenation is an additional stressor on marine life. Ocean deoxygenation results in the expansion of oxygen minimum zones in the oceans . Along with this ocean deoxygenation is caused by an imbalance of sources and sinks of oxygen in dissolved water. The change has been fairly rapid and poses a threat to fish and other types of marine life, as well as to people who depend on marine life for nutrition or livelihood. Ocean deoxygenation poses implications for ocean productivity, nutrient cycling, carbon cycling, and marine habitats.

As low oxygen zones expand vertically nearer to the surface, they can affect coastal upwelling systems such as the California Current on the coast of Oregon (US). These upwelling systems are driven by seasonal winds that force the surface waters near the coast to move offshore, which pulls deeper water up along the continental shelf. As the depth of the deoxygenated deeper water becomes shallower, more of the deoxygenated water can reach the continental shelf, causing coastal hypoxia and fish kills. Impacts of massive fish kills on the aquaculture industry are projected to be profound.

Marine organisms and biodiversity

Short term effects can be seen in acutely fatal circumstances, but other sublethal consequences can include impaired reproductive ability, reduced growth, and increase in diseased population. These can be attributed to the co-stressor effect. When an organism is already stressed, for example getting less oxygen than it would prefer, it does not do as well in other areas of its existence like reproduction, growth, and warding off disease. Additionally, warmer water not only holds less oxygen, but it also causes marine organisms to have higher metabolic rates, resulting in them using up available oxygen more quickly, lowering the oxygen concentration in the water even more and compounding the effects seen. Finally, for some organisms, habitat reduction will be a problem. Habitable zones in the water column are expected to compress and habitable seasons are expected to be shortened. If the water an organism's regular habitat sits in has oxygen concentrations lower than it can tolerate, it will not want to live there anymore. This leads to changed migration patterns as well as changed or reduced habitat area.

Long term effects can be seen on a broader scale of changes in biodiversity and food web makeup. Due to habitat change of many organisms, predator-prey relationships will be altered. For example, when squeezed into a smaller well-oxygenated area, predator-prey encounter rates will increase, causing an increase in predation, potentially putting strain on the prey population. Additionally, diversity of ecosystems in general is expected to decrease due to decrease in oxygen concentrations.

Effects on fisheries

Vertical expansion of tropical OMZs has reduced the area between the OMZ and surface. This means that many species that live near the surface, such as fish, could be affected periodically. Ongoing research is investigating how OMZ expansion affects food webs in these areas. Studies on OMZ expansion in the tropical Pacific and Atlantic have observed negative effects on fish populations and commercial fisheries that likely occurred from reduced habitat when the OMZ moved to a shallower depth.

A fish's behavior in response to ocean deoxygenation is based upon their tolerance to oxygen poor conditions. Species with low anoxic tolerance tend to undergo habitat compression in response to the expansion of OMZs. Fish species with a low tolerance for low oxygen conditions may move to live nearer the ocean surface where oxygen concentration will usually be higher. Biological responses to habitat compression can be varied. Some species of billfish, predatory pelagic predators such as sailfish and marlin, that have undergone habitat compression actually have increased growth since their prey, smaller pelagic fish, experienced the same habitat compression, resulting in increased prey vulnerability to billfishes. Fish with tolerance to anoxic conditions, such as jumbo squid and lanternfish, can remain active in anoxic environments at a reduced level, which can improve their survival by increasing avoidance of anoxia intolerant predators and have increased access to resources that their anoxia intolerant competitors cannot.

The relationship between zooplankton and low oxygen zones is complex and varies by species and life stage. Some gelatinous zooplankton reduce their growth rates when exposed to hypoxia while others utilize this habitat to forage on high prey concentrations with their growth rates unaffected. The ability of some gelatinous zooplankton to tolerate hypoxia may be attributed to the ability to store oxygen in intragel regions. The movements of zooplankton as a result of ocean deoxygenation can affect fisheries, global nitrogen cycling, and trophic relationships. These changes have the potential to have large economic and environmental consequences through overfishing or collapsed food webs.