https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indigenous_response_to_colonialism

Indigenous response to colonialism has varied depending on the Indigenous group, historical period, territory, and colonial state(s) they have interacted with. Indigenous peoples have had agency in their response to colonialism. They have employed armed resistance, diplomacy, and legal procedures. Others have fled to inhospitable, undesirable or remote territories to avoid conflict. Nevertheless, some Indigenous peoples were forced to move to reservations or reductions, and work in mines, plantations, construction, and domestic tasks. They have detribalized and culturally assimilated into colonial societies. On occasion, Indigenous peoples have formed alliances with one or more Indigenous or non-Indigenous nations. Overall, the response of Indigenous peoples to colonialism during this period has been diverse and varied in its effectiveness. Indigenous resistance has a centuries-long history that is complex and carries on into contemporary times.

Background

Indigenous peoples are the earliest known inhabitants of a territory that was or remains colonized by a dominant group. Before the age of colonialism, there were hundreds of nations and tribes throughout the territories that would be colonized, with diverse languages, religions and cultures. The peoples that would come to be known as Indigenous had large cities, city-states, chiefdoms, states, kingdoms, republics, confederacies, and empires. These societies had varying degrees of knowledge of the arts, agriculture, engineering, architecture, mathematics, astronomy, writing, physics, medicine, irrigation, geology, mining, weather forecasting, navigation, metallurgy and more. Their population would experience a significant collapse due to the effects of colonization. Most Indigenous groups in the world today have been displaced from some or all of their ancestral lands. Indigenous peoples have existed in a context of colonialism, as they are not "Indigenous" without experiencing the practice of colonialism, that is, when their sovereignty and self-determination are realized.

In recent decades, non-Indigenous historiography has paid increased attention to Indigenous agency. Before, Indigenous peoples were studied as passive objects of colonial policy and administration, but now the growing areas of borderland studies and Indigenous agency have emerged.

As European colonialism has spread throughout the world, settlers have become dominant through conquest, occupation, or invasion. In this process, there has been and continues to be conflict between settlers and Indigenous peoples. For hundreds of years in recent history, Indigenous groups have been the target of a number of atrocity crimes including multiple genocides that have destroyed entire nations. In spite of this, Indigenous peoples survive and some are thriving. They account for a population of 476 million, residing in 90 countries around the world and speaking over 5000 languages from several language families, even though hundreds of Indigenous groups are extinct. Some examples of important surviving Indigenous languages include Aymara, Guaraní, Quechua and Mapuche in South America; Lakota and Navajo in North America; Maya and Nahua in Central America; Inuit in the circumpolar region; Sámi in northwest Eurasia; and Torres Strait Islanders and Māori in Oceania. For comparison, at the time of contact in 1492, there were 40 to 70 languages spoken in Europe, mostly from the Indo-European language family.

Indigenous peoples continue to struggle as they suffer discrimination in most countries where they coexist with non-Indigenous peoples. The majority of the world's Indigenous peoples are among the poorest groups within the states where they live, and they amount to 19% of the world's poor.

Contact and conquest

Before Europeans set out to discover what had been populated by others in their Age of Discovery and before the European colonization, Indigenous peoples resided in a large proportion of the world's territory. For example, in the Americas, there are estimates of a population of up to 100 million people. The Indigenous response to colonization has been varied and also changed over time as each group chose to flee, fight, submit, support or seek diplomatic solutions. One example of an Indigenous group that fled is the Beothuk in Newfoundland, which is now practically extinct. The Charrúa were massacred in what is now Uruguay and were completely destroyed. In contrast, the Nenets have accommodated the Russian state.

For a long time, scholars have explained that the large fatality rates of Indigenous peoples upon contact with settlers have been caused by new infectious diseases brought to Indigenous territories from overseas. Recent scholarship has shifted to explore the nature of the difficult conditions of life imposed on Indigenous peoples due to colonization itself, which made Indigenous peoples more vulnerable to any disease, including new diseases. In other words, causes of death such as forced labor combined with hunger that converged during the colonization process made Indigenous peoples weaker and less resistant to disease. For example, scholars maintain that smallpox probably killed a third of the population in colonial Mexico but admit that there is no evidence to quantify the impact with certainty.

During the colonization of New Spain from the 16th to the 18th centuries, the focus of the colonizers was to practice agriculture, farming, mining, and infrastructure construction while exploiting Indigenous labor. Slavery was one of the main factors that decimated the Indigenous population of North America. Indigenous slavery predated and outlasted the African slave trade until the 20th century. The Spanish crown allowed slavery of Indigenous peoples captured in "just wars", which included Indigenous resistance to colonialism, such as religious conversion or forced labor. Indigenous forced labor took place in repartimientos, encomiendas, Spanish missions and haciendas. Indigenous women and children were forced to do domestic work. Even after slavery was outlawed by the Spanish Empire, and then ex-colonies such as the Mexican and United States governments, those that benefitted from slavery used legal frameworks to avoid enforcement such as vagrancy laws, convict leasing, and debt peonage.

Indigenous nations sought diplomacy or military alliances to survive, seeking allies in other nations, including neighbouring Indigenous nations and other colonizing powers, as in the French and Indian War and the War of 1812. In Central America, Miskito people allied with the English to resist Spanish colonialism. Indigenous peoples have sought alliances if the alliance has improved their chances of survival or worked to their advantage. Some Indigenous nations attempted to show their allegiance to the colonizing power by becoming a military ally in the attacks of other Indigenous nations, as in the case of the Tlaxcalans in the central valley of Mexico. Other times, they would ally themselves with escaped African slaves, as in the case of the Seminoles.

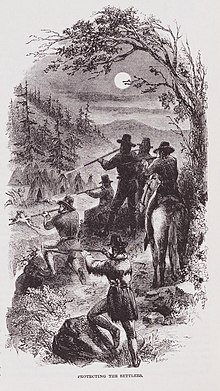

On rare occasions, Indigenous peoples would be successful in battle against European armies. Examples include the Battle of Curalaba, La Noche Triste, Chichimeca War and the Battle of Big Horn. The Mapuche in Chile, the Māori in New Zealand, the Yaquis in Mexico, and the Seminoles in Florida resisted for decades or even centuries. However, in many parts of the world, Indigenous peoples moved away from fertile, resource-rich territories to inaccessible and inhospitable territories such as swamps, deserts and jungles. They were displaced from fertile places in Argentina, Brazil, the Philippines and temperate Africa. Some examples include small Indigenous groups moving to parts of the Amazon basin, Australia, Central America, the Arctic and Siberia. Others came into conflict with other Indigenous groups as they were forcefully displaced and occupied territory that was inhabited by other Indigenous groups. On occasions, the reaction of Indigenous peoples to attacks resulted in their transformation into warrior horse cultures that used European fire guns to resist further invasion of their territories. Even today, the stereotypical Native American depicted in Indian Wars is riding on a horse. For example, the people of the Great Plains and Mapuche adopted the horse into their everyday cultures.

Indigenous peoples also adopted newly introduced domestic animals in their diet as Europeans introduced chicken, cattle, pigs, goats, and sheep in the Columbian exchange. Indigenous peoples have hunted their territory for centuries or millennia, and many times killed the animals belonging to settlers, and this has been the cause of much conflict between settlers and Indigenous peoples.

Indigenous peoples were not always conquered militarily, as in the case of treaties made between Great Britain and France with Indigenous peoples. The 1840 Treaty of Waitangi of the Maori, and the 1868 Treaty of Bosque Redondo of the Navajo are two examples of treaties that remain important today.

Colonization

Modern colonialism that started in the 15th century, along with European transatlantic navigation, resulted in the expansion of European empires and the associated settler colonialism that occurred in the Americas, Oceania, South Africa and beyond.

According to historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, the fact that Indigenous peoples survive today against genocidal attacks is proof of resistance:

Native nations and communities, while struggling to maintain fundamental values and collectivity, have from the beginning resisted modern colonialism using both defensive and offensive techniques, including the modern forms of armed resistance of national liberation movements and what now is called terrorism. In every instance they have fought for survival as peoples.

Dunbar-Ortiz sets examples of resistance in North America in the cases of the Pueblo Revolt, the Pequot War, King Philip's War, and the Seminole Wars.

Historical Indigenous resistance leaders throughout the world include Cajemé, Caupolican, Dundalli, Geronimo, Lautaro, Lempira, Mangas Coloradas, Manco Inca, Tupac Amaru II, Tecumseh, and Tenskwatawa.

At times, Indigenous peoples used violent resistance, at times successfully or at times involving two or more Indigenous allies. Examples include the Mixton rebellion, the Zapatista uprising, the Caste War of Yucatán, Rebellion of Tupac Amaru II, the Tzeltal Rebellion of 1712, Pontiac's War and the North-West Rebellion. Academic Benjamin Madley said that throughout the world, groups targeted for annihilation resist, often violently. He details the case of the Modoc War comparing the casualties of the conflict. Furthermore, he says that "The Modoc genocide is hardly the only genocide against Indigenous people that has been sanitized as war." According to Frank Chalk, in the 19th century United States, the federal government policy toward Native Americans was ethnocide, but when they resisted, the result sometimes was genocidal. Historically, victims of genocide have resisted, and this resistance has been criminalized to justify massacres.

According to Ken Coates, sexual relations between Indigenous women and non-Indigenous men took place to some extent in New Zealand, New Spain, the Metis in Canada, whereas they generally did not take place in other places such as Australia and British North America. People of mixed settler-Indigenous ancestry have been discriminated against. The mixing blurred the lines between Indigenous and newcomer populations, and most learned the language of the colony, which was a European language. Some scholars have argued that the concept of mestizaje, the process of transcultural mixing, has been used to promote assimitionalism and monoculturalism in Latin America.

In North America, where the British made treaties with Indigenous peoples, they learned that these treaties could be broken and would not protect their communities. Faced with the risk that their people would be destroyed, leaders of Indian resistance agreed to treaties requiring land cessions, and the redefinition of borders in the hope that the settlers would not encroach further on Indigenous territory. One of such examples is the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians, a federally recognized Indian Nation, which was led by Potawatomi leader Leopold Pokagon. Other times, treaties were signed under coercion or right after Indigenous groups suffered massacres, such as in the case of the Treaty of Hartford of 1638. Colonial powers also sought control of new territories by appropriating the Indigenous elite through bribery and assimilation.

In North America, the United States and Canada established residential schools, removing Indigenous children from their families for years while prohibiting the use of their Indigenous language and cultural practices. Australia focused on children with mixed ethnicity and removed children to be placed in residential schools or to be adopted by non-Indigenous families. Canada and the United States have assimilated Indigenous peoples via Indian termination policies, in which incentives are offered for Indigenous peoples to renounce Indigenous rights in exchange for benefits such as citizenship rights. Furthermore, Canada removed Indigenous rights if an Indigenous woman married a non-Indigenous person, an Indigenous person graduated from university, or joined the military.

The Cherokee Nation is one of the federally recognized tribes within the United States. It is now located in Oklahoma after being forcefully removed in the Trail of Tears along with other Indigenous groups. Indigenous groups in North America were assigned to small reservations, typically on remote and economically marginal territories that would not support crops, fishing or hunting. Some of the reservations were then dismantled through an allotment process such as the Dawes act in North America, but some Indigenous peoples refused to sign.

A 2009 United Nations report stated that Indigenous peoples have "...documented histories of resistance, interface or cooperation with states...Indigenous peoples were often recognized as sovereign peoples by states, as witnessed by the hundreds of treaties concluded between Indigenous peoples and the governments of the United States, Canada, New Zealand and others".

Contemporary response

Strategies

Indigenous strategies continue to pursue Indigenous rights and freedom and seek to rebuild their nations and cultures to maintain national groups with distinct cultural identities. Indigenous nations continue to pursue self-determination and sovereignty.

Contemporary Indigenous strategies have included negotiations, mediation, arbitration, political statements, blockades, legal challenges, activism, political demonstrations and civil disobedience. A few have worked on the removal from public spaces of symbols of Indigenous oppression, such as monuments to Christopher Columbus, John A. Macdonald, and Junipero Serra. Much resistance has also been used to bring Indigenous issues to public attention.

Indigenous peoples commemorate historical events and processes on an annual or periodic basis. Examples include Unthanksgiving Day and Indigenous Peoples Day. Activists have also protested what they consider controversial colonial holidays, such as Australia Day, and Columbus Day and its quincentenary celebration.

Erich Steinman has compiled a record of Native American resistance processes and responses that he says are not well studied by American sociology.

In New Zealand and Ecuador, Indigenous peoples have formed political parties, Te Pāti Māori and Pachakutik respectively. Bolivia has had an Indigenous president, Evo Morales.

Indigenous nations and peoples have managed to survive despite sustained long-term attacks to their survival as Indigenous nations, cultures or as members of an Indigenous group. Hall argues that Indigenous peoples challenge the idea that the state is the basic form of political organization. He argues that the Indigenous fight for self-determination today is part of a cycle of centuries of resistance to colonialism.

Views on ongoing colonialism

Elaine Coburn and historian Lorenzo Veracini say that colonialism is present in contemporary settler colonial states, including Canada, New Zealand, Australia, and the United States. Michael Grewcock has argued that in Australia, there are Indigenous peoples "who still resist the colonization of country that was never ceded".

Native American anthropologist Audra Simpson argues that the colonial project is ongoing, as the case of the Mohawks of Kahnawake, a self-governing territory of the Mohawk Nation within the borders of Canada.

Pablo G. Casanova has said that in Mexico there has been a practice of internal colonialism. According to sociologist Anibal Quijano, Bolivia and Mexico have undergone limited decolonialization through a revolutionary process. In Mexico, the case of the Ejercito Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (EZLN) denotes resistance in many areas, including education, territorial, epistemological, political and economic terms. EZLN is viewed as a continuation of the struggle against more than 500 years of oppression of Indigenous peoples.

According to Ken Coates, liberal democracies do not like being called up on internal human rights abuses "when these same governments are often prominent in criticizing other nations for abuses of human and civil rights". Furthermore, post-independence era countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia have been dismissive of Indigenous rights as much as colonial empires.

Indigenous storytelling

Oral storytelling is important to Indigenous culture, but it has been underepresented. Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz has said that when Howard Zinn wrote his United States' history book, he did not include the history of the Indigenous peoples, so he said that she could write what would become such a book: An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States. Rigoberta Menchu published an essay about her life with personal experiences directly related to the Guatemalan genocide and went on to win the Nobel Peace Prize.

Truth commissions

There are Truth Commissions that have investigated and reported on Indigenous atrocities. Some of them include the Guatemala Historical Clarification Commission, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Norway.

Museums

In Latin America, there are only a few museums whose central theme is that of colonization and history of Indigenous peoples.

Indigenous peoples and others have protested against museum´s exhibitions. Notable examples of Indigenous museums are Museu do Índio (Rio de Janeiro, Brasil), Royal Museum for Central Africa (Brussels, Belgium), Musée du Quai Branly (Paris, France), National Museum of Anthropology (Mexico City), Museum of the Tropics (Amsterdam, Netherlands), Museo Nacional de Antropología and Museo de América (Madrid, Spain), American Indian Genocide Museum (Houston, USA), George Gustav Heye Center (New York City, USA), and National Museum of the American Indian (Washington, D.C., USA).

Many smaller European colonial museums have closed after the end of European colonization. According to Pascal Blanchard, the political climate in France has not allowed the emergence of a museum about French colonialism. In Bristol, England, the only museum dedicated to colonialism, British Empire and Commonwealth Museum, has been closed after operating for just 6 years.

In North America, American Museum of Natural History in New York, Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History, Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology and Cleveland Museum of Art have begun to close exhibits with Indigenous themes to comply with federal regulations that mandate tribal consent and repatriation of human remains.

Indigenous media

There are a number of Indigenous broadcasting organizations from countries serving Indigenous themes, including APTN, First Nations Experience, NITV, NRK Sami and Whakaata Māori.

Language

Some movements, such as the Hawaiian sovereignty movement, have sought to promote the use of Indigenous languages in educational programs. In recent years, there has been a revival in the use of Māori language in New Zealand, where it is an official language and taught in 350 schools. New technologies are making access to educational language programs accessible to the general public. Furthermore, there are examples of Indigenous schools that move away from Eurocentric curriculums while considering the graduates' future prospects within a non-Indigenous majority state. In Paraguay, Guaraní is the official language and is spoken by 6.5 million people in the region. Quechua and Aymara are official languages in Peru and Bolivia and are spoken by 8 and 2.5 million people, respectively. Nationalism has promoted the use of local languages in most of Eurasia, but in the rest of the world, European languages remain dominant in mass media, education and the internet.

Culture

Today, Indigenous peoples can react to cultural processes in various ways, including acculturation, transculturation, assimilation, and cultural loss, while some remain separated from the dominant culture or marginalized from any group, including their own. In Hispanic America, Indigenous peoples have adopted Spanish religion, institutions, language, and literature, as well as non-endemic domestic animals and crops.

Some scholars and Indigenous peoples argue that renaming geographical entities should be part of a reclaiming process of Indigenous cultures.

International law

In the area of international law, the Working Group on Indigenous Populations participated directly in the development of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and worked on the development of the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention of 1989. Indigenous scholar Jeff Corntassel said that article 46 of UNDRIP may be detrimental to some Indigenous rights: "...the restoration of their land-based and water-based cultural relationships and practices is often portrayed as a threat to the territorial integrity of the country(ies) in which they reside, and thus, a threat to state sovereignty".

For decades, Indigenous peoples had demanded that the Catholic Church rescinded the Doctrine of Discovery theories that justified the seizure of Indigenous land and supported a legal basis.