During the High Middle Ages, the Islamic world was at its cultural peak, supplying information and ideas to Europe, via Al-Andalus, Sicily and the Crusader kingdoms in the Levant. These included Latin translations of the Greek Classics and of Arabic texts in astronomy, mathematics, science, and medicine. Translation of Arabic philosophical texts into Latin "led to the transformation of almost all philosophical disciplines in the medieval Latin world", with a particularly strong influence of Muslim philosophers being felt in natural philosophy, psychology and metaphysics. Other contributions included technological and scientific innovations via the Silk Road, including Chinese inventions such as paper, compass and gunpowder.

The Islamic world also influenced other aspects of medieval European culture, partly by original innovations made during the Islamic Golden Age, including various fields such as the arts, agriculture, alchemy, music, pottery, etc.

Many Arabic loanwords in Western European languages, including English, mostly via Old French, date from this period. This includes traditional star names such as Aldebaran, scientific terms like alchemy (whence also chemistry), algebra, algorithm, etc. and names of commodities such as sugar, camphor, cotton, coffee, etc.

Transmission routes

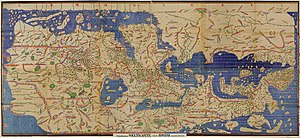

Europe and the Islamic lands had multiple points of contact during the Middle Ages. The main points of transmission of Islamic knowledge to Europe lay in Sicily and in Spain, particularly in Toledo (with Gerard of Cremone, 1114–1187, following the conquest of the city by Spanish Christians in 1085). In Sicily, following the Islamic conquest of the island in 965 and its reconquest by the Normans in 1091, a syncretistic Norman–Arab–Byzantine culture developed, exemplified by rulers such as King Roger II, who had Islamic soldiers, poets and scientists at his court. The Moroccan Muhammad al-Idrisi wrote The Book of Pleasant Journeys into Faraway Lands or Tabula Rogeriana, one of the greatest geographical treatises of the Middle Ages, for Roger.

The Crusades also intensified exchanges between Europe and the Levant, with the Italian maritime republics taking a major role in these exchanges. In the Levant, in such cities as Antioch, Arab and Latin cultures intermixed intensively.

During the 11th and 12th centuries, many Christian scholars traveled to Muslim lands to learn sciences. Notable examples include Leonardo Fibonacci (c. 1170 –c. 1250), Adelard of Bath (c. 1080–c. 1152) and Constantine the African (1017–1087). (inaccurate: None of the three mentioned actually "traveled to Muslim lands to learn sciences", Constantine may possibly have been born there in Arab lands, Fibonacci found himself there for family reasons, while Adelard probably learnt Arabic in Christian lands). From the 11th to the 14th centuries, numerous European students attended Muslim centers of higher learning (which the author calls "universities") to study medicine, philosophy, mathematics, cosmography and other subjects.

Aristotelianism and other philosophies

In the Middle East, many classical Greek texts, especially the works of Aristotle, were translated into Syriac during the 6th and 7th centuries by Nestorian, Melkite or Jacobite monks living in Palestine, or by Greek exiles from Athens or Edessa who visited Islamic centres of higher learning. The Islamic world then kept, translated, and developed many of these texts, especially in centers of learning such as Baghdad, where a "House of Wisdom" with thousands of manuscripts existed as early as 832. These texts were in turn translated into Latin by scholars such as Michael Scot (who made translations of Historia Animalium and On the Soul as well as of Averroes's commentaries) during the Middle Ages. Eastern Christians played an important role in exploiting this knowledge, especially through the Christian Aristotelian School of Baghdad in the 11th and 12th centuries.

Later Latin translations of these texts originated in multiple places. Toledo, Spain (with Gerard of Cremona's Almagest) and Sicily became the main points of transmission of knowledge from the Islamic world to Europe. Burgundio of Pisa (died 1193) discovered lost texts of Aristotle in Antioch and translated them into Latin.

From Islamic Spain, the Arabic philosophical literature was translated into Hebrew, Latin, and Ladino. The Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides, Muslim sociologist-historian Ibn Khaldun, Carthage citizen Constantine the African who translated Greek medical texts, and Al-Khwarizmi's collation of mathematical techniques were important figures of the Golden Age.

Avicennism and Averroism are terms for the revival of the Peripatetic school in medieval Europe due to the influence of Avicenna and Averroes, respectively. Avicenna was an important commentator on the works of Aristotle, modifying it with his own original thinking in some areas, notably logic. The main significance of Latin Avicennism lies in the interpretation of Avicennian doctrines such as the nature of the soul and his existence-essence distinction, along with the debates and censure that they raised in scholastic Europe. This was particularly the case in Paris, where so-called Arabic culture was proscribed in 1210, though the influence of his psychology and theory of knowledge upon William of Auvergne and Albertus Magnus have been noted.

The effects of Avicennism were later submerged by the much more influential Averroism, the Aristotelianism of Averroes, one of the most influential Muslim philosophers in the West. Averroes disagreed with Avicenna's interpretations of Aristotle in areas such as the unity of the intellect, and it was his interpretation of Aristotle which had the most influence in medieval Europe. Dante Aligheri argues along Averroist lines for a secularist theory of the state in De Monarchia. Averroes also developed the concept of "existence precedes essence".

Al-Ghazali also had an important influence on medieval Christian philosophy along with Jewish thinkers like Maimonides.

George Makdisi (1989) has suggested that two particular aspects of Renaissance humanism have their roots in the medieval Islamic world, the "art of dictation, called in Latin, ars dictaminis," and "the humanist attitude toward classical language". He notes that dictation was a necessary part of Arabic scholarship (where the vowel sounds need to be added correctly based on the spoken word), and argues that the medieval Italian use of the term "ars dictaminis" makes best sense in this context. He also believes that the medieval humanist favouring of classical Latin over medieval Latin makes most sense in the context of a reaction to Arabic scholarship, with its study of the classical Arabic of the Koran in preference to medieval Arabic.

Sciences

During the Islamic Golden Age, certain advances were made in scientific fields, notably in mathematics and astronomy (algebra, spherical trigonometry), and in chemistry, etc. which were later also transmitted to the West.

Stefan of Pise translated into Latin around 1127 an Arab manual of medical theory. The method of algorism for performing arithmetic with the Hindu–Arabic numeral system was developed by the Persian al-Khwarizmi in the 9th century, and introduced in Europe by Leonardo Fibonacci (1170–1250). A translation by Robert of Chester of the Algebra by al-Kharizmi is known as early as 1145. Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen, 980–1037) compiled treatises on optical sciences, which were used as references by Newton and Descartes. Medical sciences were also highly developed in Islam as testified by the Crusaders, who relied on Arab doctors on numerous occasions. Joinville reports he was saved in 1250 by a "Saracen" doctor.

Contributing to the growth of European science was the major search by European scholars such as Gerard of Cremona for new learning. These scholars were interested in ancient Greek philosophical and scientific texts (notably the Almagest) which were not obtainable in Latin in Western Europe, but which had survived and been translated into Arabic in the Muslim world. Gerard was said to have made his way to Toledo in Spain and learnt Arabic specifically because of his "love of the Almagest". While there he took advantage of the "abundance of books in Arabic on every subject". Islamic Spain and Sicily were particularly productive areas because of the proximity of multi-lingual scholars. These scholars translated many scientific and philosophical texts from Arabic into Latin. Gerard personally translated 87 books from Arabic into Latin, including the Almagest, and also Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī's On Algebra and Almucabala, Jabir ibn Aflah's Elementa astronomica, al-Kindi's On Optics, Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Kathīr al-Farghānī's On Elements of Astronomy on the Celestial Motions, al-Farabi's On the Classification of the Sciences, the chemical and medical works of Rhazes, the works of Thabit ibn Qurra and Hunayn ibn Ishaq, and the works of Arzachel, Jabir ibn Aflah, the Banū Mūsā, Abū Kāmil Shujā ibn Aslam, Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi (Abulcasis), and Ibn al-Haytham (including the Book of Optics).

Alchemy

Western alchemy was directly dependent upon Arabic sources. Latin translations of Arabic alchemical works such as those attributed to Khalid ibn Yazid (Latin: Calid), Jabir ibn Hayyan (Latin: Geber), Abu Bakr al-Razi (Latin: Rhazes) and Ibn Umayl (Latin: Senior Zadith) were standard texts for European alchemists. Some important texts translated from the Arabic include the Liber de compositione alchemiae ("Book on the Composition of Alchemy") attributed to Khalid ibn Yazid and translated by Robert of Chester in 1144, the Liber de septuaginta ("Book of Seventy") attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan and translated by Gerard of Cremona (before 1187), Abu Bakr al-Razi's Liber secretorum Bubacaris, and Ibn Umayl's Tabula chemica.

Many texts were also translated from anonymous Arabic sources and then falsely attributed to various authors, as for example the De aluminibus et salibus ("On Alums and Salts"), an 11th- or 12th-century text attributed in some manuscripts to Hermes Trismegistus or Abu Bakr al-Razi. Other texts were directly written in Latin but still attributed to Arabic authors, such as the influential Summa perfectionis ("The Sum of Perfection") and other 13th-/14th-century works by pseudo-Geber. Although these were original and often innovative texts, their anonymous authors probably knew Arabic and were still intimately familiar with Arabic sources.

Several technical Arabic words from Arabic alchemical works, such as alkali, found their way into European languages and became part of scientific vocabulary.

Astronomy, mathematics and physics

The translation of Al-Khwarizmi's work greatly influenced mathematics in Europe. As Professor Victor J. Katz writes: "Most early algebra works in Europe in fact recognized that the first algebra works in that continent were translations of the work of al-Khwärizmï and other Islamic authors. There was also some awareness that much of plane and spherical trigonometry could be attributed to Islamic authors". The words algorithm, deriving from Al-Khwarizmi's Latinized name Algorismi, and algebra, deriving from the title of his AD 820 book Hisab al-jabr w’al-muqabala, Kitab al-Jabr wa-l-Muqabala are themselves Arabic loanwords. This and other Arabic astronomical and mathematical works, such as those by al-Battani and Muhammad al-Fazari's Great Sindhind (based on the Surya Siddhanta and the works of Brahmagupta). were translated into Latin during the 12th century.

Al-Khazini's Zij as-Sanjari (1115–1116) was translated into Greek by Gregory Chioniades in the 13th century and was studied in the Byzantine Empire. The astronomical modifications to the Ptolemaic model made by al-Battani and Averroes led to non-Ptolemaic models produced by Mo'ayyeduddin Urdi (Urdi lemma), Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī (Tusi-couple) and Ibn al-Shatir, which were later adapted into the Copernican heliocentric model. Abū al-Rayhān al-Bīrūnī's Ta'rikh al-Hind and Kitab al-qanun al-Mas’udi were translated into Latin as Indica and Canon Mas’udicus respectively.

Fibonacci presented the first complete European account of Arabic numerals and the Hindu–Arabic numeral system in his Liber Abaci (1202).

Al-Jayyani's The book of unknown arcs of a sphere (a treatise on spherical trigonometry) had a "strong influence on European mathematics". Regiomantus' On Triangles (c. 1463) certainly took his material on spherical trigonometry (without acknowledgment) from Arab sources. Much of the material was taken from the 12th-century work of Jabir ibn Aflah, as noted in the 16th century by Gerolamo Cardano.

A short verse used by Fulbert of Chartres (952-970 –1028) to help remember some of the brightest stars in the sky gives us the earliest known use of Arabic loanwords in a Latin text: "Aldebaran stands out in Taurus, Menke and Rigel in Gemini, and Frons and bright Calbalazet in Leo. Scorpio, you have Galbalagrab; and you, Capricorn, Deneb. You, Batanalhaut, are alone enough for Pisces."

Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) wrote the Book of Optics (1021), in which he developed a theory of vision and light which built on the work of the Roman writer Ptolemy (but which rejected Ptolemy's theory that light was emitted by the eye, insisting instead that light rays entered the eye), and was the most significant advance in this field until Kepler. The Book of Optics was an important stepping stone in the history of the scientific method and history of optics. The Latin translation of the Book of Optics influenced the works of many later European scientists, including Roger Bacon and Johannes Kepler. The book also influenced other aspects of European culture. In religion, for example, John Wycliffe, the intellectual progenitor of the Protestant Reformation, referred to Alhazen in discussing the seven deadly sins in terms of the distortions in the seven types of mirrors analyzed in De aspectibus. In literature, Alhazen's Book of Optics is praised in Guillaume de Lorris' Roman de la Rose. In art, the Book of Optics laid the foundations for the linear perspective technique and may have influenced the use of optical aids in Renaissance art (see Hockney-Falco thesis). These same techniques were later employed in the maps made by European cartographers such as Paolo Toscanelli during the Age of Exploration.

The theory of motion developed by Avicenna from Aristotelian physics may have influenced Jean Buridan's theory of impetus (the ancestor of the inertia and momentum concepts). The work of Galileo Galilei on classical mechanics (superseding Aristotelian physics) was also influenced by earlier medieval physics writers, including Avempace.

Other notable works include those of Nur Ed-Din Al Betrugi, notably On the Motions of the Heavens, Abu Ma'shar al-Balkhi's Introduction to Astrology, Abū Kāmil Shujā ibn Aslam's Algebra, and De Proprietatibus Elementorum, an Arabic work on geology written by a pseudo-Aristotle.

Medicine

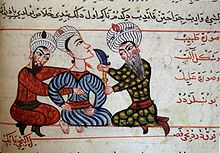

One of the most important medical works to be translated was Avicenna's The Canon of Medicine (1025), which was translated into Latin and then disseminated in manuscript and printed form throughout Europe. It remained a standard medical textbook in Europe until the early modern period, and during the 15th and 16th centuries alone, The Canon of Medicine was published more than thirty-five times. Avicenna noted the contagious nature of some infectious diseases (which he attributed to "traces" left in the air by a sick person), and discussed how to effectively test new medicines. He also wrote The Book of Healing, a more general encyclopedia of science and philosophy, which became another popular textbook in Europe. Muhammad ibn Zakarīya Rāzi wrote the Comprehensive Book of Medicine, with its careful description of and distinction between measles and smallpox, which was also influential in Europe. Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi wrote Kitab al-Tasrif, an encyclopedia of medicine which was particularly famed for its section on surgery. It included descriptions and diagrams of over 200 surgical instruments, many of which he developed. The surgery section was translated into Latin by Gerard of Cremona in the 12th century, and used in European medical schools for centuries, still being reprinted in the 1770s.

Other medical Arabic works translated into Latin during the medieval period include the works of Razi and Avicenna (including The Book of Healing and The Canon of Medicine), and Ali ibn Abbas al-Majusi's medical encyclopedia, The Complete Book of the Medical Art. Mark of Toledo in the early 13th century translated the Qur'an as well as various medical works.

Technology and culture

Agriculture and textiles

Various fruits and vegetables were introduced to Europe in this period via the Middle East and North Africa, some from as far as China and India, including the artichoke, spinach, and aubergine.

Arts

Islamic decorative arts were highly valued imports to Europe throughout the Middle Ages. Largely because of accidents of survival, most surviving examples are those that were in the possession of the church. In the early period textiles were especially important, used for church vestments, shrouds, hangings and clothing for the elite. Islamic pottery of everyday quality was still preferred to European wares. Because decoration was mostly ornamental, or small hunting scenes and the like, and inscriptions were not understood, Islamic objects did not offend Christian sensibilities. Medieval art in Sicily is interesting stylistically because of the mixture of Norman, Arab and Byzantine influences in areas such as mosaics and metal inlays, sculpture, and bronze-working.

Writing

The Arabic Kufic script was often imitated for decorative effect in the West during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, to produce what is known as pseudo-Kufic: "Imitations of Arabic in European art are often described as pseudo-Kufic, borrowing the term for an Arabic script that emphasizes straight and angular strokes, and is most commonly used in Islamic architectural decoration". Numerous cases of pseudo-Kufic are known from European art from around the 10th to the 15th century; usually the characters are meaningless, though sometimes a text has been copied. Pseudo-Kufic would be used as writing or as decorative elements in textiles, religious halos or frames. Many are visible in the paintings of Giotto. The exact reason for the incorporation of pseudo-Kufic in early Renaissance painting is unclear. It seems that Westerners mistakenly associated 13th- and 14th-century Middle-Eastern scripts as being identical with the scripts current during Jesus's time, and thus found natural to represent early Christians in association with them: "In Renaissance art, pseudo-Kufic script was used to decorate the costumes of Old Testament heroes like David". Another reason might be that artist wished to express a cultural universality for the Christian faith, by blending together various written languages, at a time when the church had strong international ambitions.

Carpets

Carpets of Middle-Eastern origin, either from the Ottoman Empire, the Levant or the Mamluk state of Egypt or Northern Africa, were a significant sign of wealth and luxury in Europe, as demonstrated by their frequent occurrence as important decorative features in paintings from the 13th century and continuing into the Baroque period. Such carpets, together with Pseudo-Kufic script offer an interesting example of the integration of Eastern elements into European painting, most particularly those depicting religious subjects.

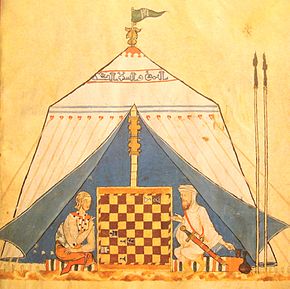

Music

A number of musical instruments used in European music were influenced by Arabic musical instruments, including the rebec (an ancestor of the violin) from the rebab and the naker from naqareh The oud is cited as one of several precursors to the modern guitar.

Some scholars believe that the troubadors may have had Arabian origins, with Magda Bogin stating that the Arab poetic and musical tradition was one of several influences on European "courtly love poetry". Évariste Lévi-Provençal and other scholars stated that three lines of a poem by William IX of Aquitaine were in some form of Arabic, indicating a potential Andalusian origin for his works. The scholars attempted to translate the lines in question and produced various different translations; the medievalist Istvan Frank contended that the lines were not Arabic at all, but instead the result of the rewriting of the original by a later scribe.

The theory that the troubadour tradition was created by William after his experiences with Moorish arts while fighting with the Reconquista in Spain has been championed by Ramón Menéndez Pidal and Idries Shah, though George T. Beech states that there is only one documented battle that William fought in Spain, and it occurred towards the end of his life. However, Beech adds that William and his father did have Spanish individuals within their extended family, and that while there is no evidence he himself knew Arabic, he may have been friendly with some European Christians who could speak the language. Others state that the notion that William created the concept of troubadours is itself incorrect, and that his "songs represent not the beginnings of a tradition but summits of achievement in that tradition."

Technology

A number of technologies in the Islamic world were adopted in European medieval technology. These included various crops; various astronomical instruments, including the Greek astrolabe which Arab astronomers developed and refined into such instruments as the Quadrans Vetus, a universal horary quadrant which could be used for any latitude, and the Saphaea, a universal astrolabe invented by Abū Ishāq Ibrāhīm al-Zarqālī; the astronomical sextant; various surgical instruments, including refinements on older forms and completely new inventions; and advanced gearing in waterclocks and automata. Distillation was known to the Greeks and Romans, but was rediscovered in medieval Europe through the Arabs. The word alcohol (to describe the liquid produced by distillation) comes from Arabic al-kuhl. The word alembic (via the Greek Ambix) comes from Arabic al-anbiq. Islamic examples of complex water clocks and automata are believed to have strongly influenced the European craftsmen who produced the first mechanical clocks in the 13th century.

The importation of both the ancient and new technology from the Middle East and the Orient to Renaissance Europe represented “one of the largest technology transfers in world history.”

In an influential 1974 paper, historian Andrew Watson suggested that there had been an Arab Agricultural Revolution between 700 and 1100, which had diffused a large number of crops and technologies from Spain into medieval Europe, where farming was mostly restricted to wheat strains obtained much earlier via central Asia. Watson listed eighteen crops, including sorghum from Africa, citrus fruits from China, and numerous crops from India such as mangos, rice, cotton and sugar cane, which were distributed throughout Islamic lands that, according to Watson, had previously not grown them. Watson argued that these introductions, along with an increased mechanization of agriculture, led to major changes in economy, population distribution, vegetation cover, agricultural production and income, population levels, urban growth, the distribution of the labour force, linked industries, cooking, diet and clothing in the Islamic world. Also transmitted via Muslim influence, a silk industry flourished, flax was cultivated and linen exported, and esparto grass, which grew wild in the more arid parts, was collected and turned into various articles. However Michael Decker has challenged significant parts of Watson's thesis, including whether all these crops were introduced to Europe during this period. Decker used literary and archaeological evidence to suggest that four of the listed crops (i.e. durum wheat, Asiatic rice, sorghum and cotton) were common centuries before the Islamic period, that the crops which were new were not as important as Watson had suggested, and generally arguing that Islamic agricultural practices in areas such as irrigation were more of an evolution from those of the ancient world than the revolution suggested by Watson.

The production of sugar from sugar cane, water clocks, pulp and paper, silk, and various advances in making perfume, were transferred from the Islamic world to medieval Europe. Fulling mills and advances in mill technology may have also been transmitted from the Islamic world to medieval Europe, along with the large-scale use of inventions like the suction pump, noria and chain pumps for irrigation purposes. According to Watson, "The Islamic contribution was less in the invention of new devices than in the application on a much wider scale of devices which in pre-Islamic times had been used only over limited areas and to a limited extent." These innovations made it possible for some industrial operations that were previously served by manual labour or draught animals to be driven by machinery in medieval Europe.

The spinning wheel was invented in the Islamic world by 1030. It later spread to China by 1090, and then spread from the Islamic world to Europe and India by the 13th century. The spinning wheel was fundamental to the cotton textile industry prior to the Industrial Revolution. It was a precursor to the spinning jenny, which was widely used during the Industrial Revolution. The spinning jenny was essentially an adaptation of the spinning wheel.

Coinage

While the earliest coins were minted and widely circulated in Europe, and Ancient Rome, Islamic coinage had some influence on Medieval European minting. The 8th-century English king Offa of Mercia minted a near-copy of Abbasid dinars struck in 774 by Caliph Al-Mansur with "Offa Rex" centered on the reverse. The moneyer visibly had little understanding of Arabic, as the Arabic text contains a number of errors.

In Sicily, Malta and Southern Italy from about 913 tarì gold coins of Islamic origin were minted in great number by the Normans, Hohenstaufens and the early Angevins rulers. When the Normans invaded Sicily in the 12th century, they issued tarì coins bearing legends in Arabic and Latin. The tarìs were so widespread that imitations were made in southern Italy (Amalfi and Salerno) which only used illegible "pseudo-Kufic" imitations of Arabic.

According to Janet Abu-Lughod:

The preferred specie for international transactions before the 13th century, in Europe as well as the Middle East and even India, were the gold coins struck by Byzantium and then Egypt. It was not until after the 13th century that some Italian cities (Florence and Genoa) began to mint their own gold coins, but these were used to supplement rather than supplant the Middle Eastern coins already in circulation.

Literature

It was first suggested by Miguel Asín Palacios in 1919 that Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy, considered the greatest epic of Italian literature, derived many features of and episodes about the hereafter directly or indirectly from Arabic works on Islamic eschatology, such as the Hadith and the spiritual writings of Ibn Arabi. The Kitab al-Miraj, concerning Muhammad's ascension to Heaven, was translated into Latin in 1264 or shortly before as Liber scalae Machometi, "The Book of Muhammad's Ladder". Dante was certainly aware of Muslim philosophy, naming Avicenna and Averroes last in his list of non-Christian philosophers in Limbo, alongside the great Greek and Latin philosophers. How strong the similarities are to Kitab al-Miraj remains a matter of scholarly debate however, with no clear evidence that Dante was in fact influenced.