Chinese creation myths are symbolic narratives about the origins of the universe, earth, and life. Myths in China vary from culture to culture. In Chinese mythology, the term "cosmogonic myth" or "origin myth" is more accurate than "creation myth", since very few stories involve a creator deity or divine will. Chinese creation myths fundamentally differ from monotheistic traditions with one authorized version, such as the Judeo-Christian Genesis creation narrative: Chinese classics record numerous and contradictory origin myths. Traditionally, the world was created on Chinese New Year and the animals, people, and many deities were created during its 15 days.

Some Chinese cosmogonic myths have familiar themes in comparative mythology. For example, creation from chaos (Chinese Hundun and Hawaiian Kumulipo), dismembered corpses of a primordial being (Pangu, Indo-European Yemo and Mesopotamian Tiamat), world parent siblings (Fuxi and Nüwa and Japanese Izanagi and Izanami), and dualistic cosmology (yin and yang and Zoroastrian Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu). In contrast, other mythic themes are uniquely Chinese. While the mythologies of Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Greece believed primeval water was the single element that existed "in the beginning", the basic element of Chinese cosmology was qi ("breath; air; life force"). Anne Birrell explains that qi "was believed to embody cosmic energy governing matter, time, and space. This energy, according to Chinese mythic narratives, undergoes a transformation at the moment of creation, so that the nebulous element of vapor becomes differentiated into dual elements of male and female, Yin and Yang, hard and soft matter, and other binary elements."

Cosmogonic mythologies

Tao Te Ching

The Tao Te Ching, written sometime before the 4th century BC, suggests a less mystical Chinese cosmogony and has some of the earliest allusions to creation.

There was something featureless yet complete, born before heaven and earth; Silent—amorphous—it stood alone and unchanging. We may regard it as the mother of heaven and earth. Commonly styled "The Way."

The Way gave birth to unity, Unity gave birth to duality, Duality gave birth to trinity, Trinity gave birth to the myriad creatures. The myriad creatures bear yin on their back and embrace yang in their bosoms. They neutralize these vapors and thereby achieve harmony.

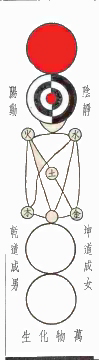

Later Taoists interpreted this sequence to mean the Tao (Dao, "Way"), formless (Wuji, "Without Ultimate"), unitary (Taiji, "Great Ultimate"), and binary (yin and yang or Heaven and Earth).

Girardot reasons that Tao Te Ching evokes the Tao as "a cosmic principle of the beginnings would seem to make little sense without seeing the possibility that it was rooted in the symbolic remembrance of archaic mythological, especially cosmogonic, themes."

Songs of Chu

The "Heavenly Questions" section of the "Chu Ci", written around the 4th century BC, begins by asking catechistic questions about creation myths. Birrell calls it "the most valuable document in Chinese mythography" and surmises an earlier date for its mythos "since it clearly draws on a preexisting fund of myths."

Who passed down the story of the far-off, ancient beginning of things? How can we be sure what it was like before the sky above and the earth below had taken shape? Since none could penetrate that murk when darkness and light were yet undivided, how do we know about the chaos of insubstantial forms? What manner of things are the darkness and light? How did Yin and Yang come together, and how did they originate and transform all things that are by their commingling? Whose compass measured out the ninefold heavens? Whose work was this, and how did he accomplish it? Where were the circling cords fastened, and where was the sky's pole fixed? Where did the Eight Pillars meet the sky, and why were they too short for it in the south-east? Where do the nine fields of heaven extend to and where do they join each other? The ins and outs of their edges must be very many: who knows their number? How does heaven coordinate its motions? Where are the Twelve Houses divided? How do the sun and the moon hold to their courses and the fixed stars keep their places?

Birrell describes this Chu creation narrative as a "vivid world picture. It mentions no prime cause, no first creator. From the "formless expanse" the primeval element of misty vapor emerges spontaneously as a creative force, which is organically constructed as a set of binary forces in opposition to each other — upper and lower spheres, darkness and light, Yin and Yang — whose mysterious transformations bring about the ordering of the universe.".

Daoyuan

The Daoyuan (道原, "Origins of the Tao") is one of the Huangdi Sijing manuscripts discovered in 1973 among the Mawangdui Silk Texts excavated from a tomb dated to 168 BC. Like the Songs of Chu above, this text is believed to date from the 4th century BC and from the same southern state of Chu. This Taoist cosmogonic myth describes the creation of the universe and humans out of formless misty vapor, and Birrell notes the striking resemblance between its ancient "all was one" concept of unity before creation and the modern cosmogonic concept of gravitational singularity.

At the beginning of eternal past all things penetrated and were identical with great vacuity, Vacuous and identical with the One, rest at the One eternally. Unsettled and confusing, there was no distinction of dark and light. Though Tao is undifferentiated, it is autonomous: "It has no cause since ancient times", yet "the ten thousand things are caused by it without any exception". Tao is great and universal on the one hand, but also formless and nameless.

Taiyi Shengshui

The 4th or 3rd century BC Taiyi Shengshui ("Great One Giving Birth to Water"), a Taoist text recently excavated in the Guodian Chu Slips, seems to offer its own unique creation myth, but analysis remains uncertain.

Huainanzi

The 139 BC Huainanzi, an eclectic text compiled under the direction of the Han prince Liu An, contains two cosmogonic myths that develop the dualistic concept of Yin and Yang:

When Heaven and Earth were yet unformed, all was ascending and flying, diving and delving. Thus it was called the Grand Inception. The Grand Inception produced the Nebulous Void. The Nebulous Void produced space-time, space-time produced the original qi. A boundary [divided] the original qi. That which was pure and bright spread out to form Heaven; that which was heavy and turbid congealed to form Earth. It is easy for that which is pure and subtle to converge but difficult for the heavy and turbid to congeal. Therefore, Hell was completed first; Earth was fixed afterward. The conjoined essences of Heaven and Earth produced yin and yang. The supersessive essences of yin and yang caused the four seasons. The scattered essences of the four seasons created the myriad things. The hot qi of accumulated yang produced fire; the essence of fiery qi became the sun. The cold qi of accumulated yin produced water; the essence of watery qi became the moon. The overflowing qi of the essences of the sun and the moon made the stars and planets. To Heaven belong the sun, moon, stars, and planets; to Earth belong waters and floods, dust and soil.

Of old, in the time before there was Heaven and Earth: There were only images and no forms. All was obscure and dark, vague and unclear, shapeless and formless, and no one knows its gateway. There were two spirits, born in murkiness, one that established Heaven and the other that constructed Earth. So vast! No one knows where they ultimately end. So broad! No one knows where they finally stop. Thereupon they differentiated into the yin and the yang and separated into the eight cardinal directions. The firm and the yielding formed each other; the myriad things thereupon took shape. The turbid vital energy became creatures; the refined vital energy became humans.

Birrell suggests this abstract Yin-Yang dualism between the two primeval spirits or gods may be the "vestige of a much older mythological paradigm that was then rationalized and diminished", comparable to the Akkadian Enûma Eliš creation myth of Abzu and Tiamat, male fresh water and female salt water.

Lingxian

The Lingxian (靈憲), written around AD 120 by the polymath Zhang Heng, thoroughly accounts for the creation of Heaven and Earth.

Before the Great Plainness [or Great Basis, Taisu, 太素] came to be, there was dark limpidity and mysterious quiescence, dim and dark. No image of it can be formed. Its midst was void; its exterior was non-existence. Things remained thus for long ages; this is called obscurity [mingxing, 溟涬]. It was the root of the Dao… When the stem of the Dao had been grown, creatures came into being and shapes were formed. At this stage, the original qi split and divided, hard and soft first divided, pure and turbid took up different positions. Heaven formed on the outside, and Earth became fixed within. Heaven took its body from the Yang, so it was round and in motion; Earth took its body from the Yin, so it was flat and quiescent. Through motion there was action and giving forth; through quiescence there was conjoining and transformation. Through binding together there was fertilization, and in time all the kinds of things were brought to growth. This is called the Great Origin [Taiyuan, 太元]. It was the fruition of the Dao.

Later texts

The Neo-Confucianist philosopher Zhou Dunyi provided a multifaceted cosmology in his Taiji Tushuo (太極圖說, "Diagram Explaining the Supreme Ultimate"), which integrated the I Ching with Taoism and Chinese Buddhism.

The Nuwa and Fuxi and Pangu mythologies

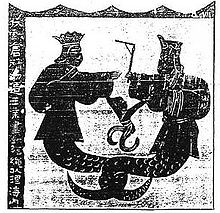

In contrast to the above Chinese cosmogonic myths about the world and humans originating spontaneously without a creator (e.g., from "refined vital energy" in the Huainanzi), two later origin myths for humans involve divinities. The female Nüwa fashioned people from loess and mud (in early myths) or from procreating with her brother/husband Fuxi (in later versions). Myths about the male Pangu say that people derived from mites on his corpse.

Nüwa

In Chinese mythology, the goddess Nüwa repaired the fallen pillars holding up the sky, creating human beings either before or after. The ancient Chinese believed in a square earth and a round, domelike sky supported by eight giant pillars (cf. the European ideas of an axis mundi).

The "Heavenly Questions" of the Songs of Chu from around the 4th century BC is the first surviving text that refers to Nüwa: "By what law was Nü Wa raised up to become high lord? By what means did she fashion the different creatures?"

Two Huainanzi chapters record Nüwa mythology two centuries later:

Going back to more ancient times, the four [of 8] pillars were broken; the nine provinces were in tatters. Heaven did not completely cover [the earth]; Earth did not hold up [Heaven] all the way around [its circumference]. Fires blazed out of control and could not be extinguished; water flooded in great expanses and would not recede. Ferocious animals ate blameless people; predatory birds snatched the elderly and the weak. Thereupon, Nüwa smelted together five-colored stones in order to patch up the azure sky, cut off the legs of the great turtle to set them up as the four pillars, killed the black dragon to provide relief for Ji Province, and piled up reeds and cinders to stop the surging waters. The azure sky was patched; the four pillars were set up; the surging waters were drained; the province of Ji was tranquil; crafty vermin died off; blameless people [preserved their] lives. Bearing the square [nine] provinces on her back and embracing Heaven, [Fuxi and Nüwa established] the harmony of spring and the yang of summer, the slaughtering of autumn and the restraint of winter.

The Yellow Emperor produced yin and yang. Shang Pian produced ears and eyes; Sang Lin produced shoulders and arms. Nüwa used these to carry out the seventy transformations?

Shang Pian (上駢) and Sang Lin (桑林) are obscure mythic divinities. The commentary of Xu Shen written around AD 100 says "seventy transformations" refers to Nuwa's power to create everything in the world.

The Fengsu Tongyi ("Common Meanings in Customs"), written by Ying Shao around AD 195, describes Han-era beliefs about the primeval goddess.

People say that when Heaven and earth opened and unfolded, humankind did not yet exist, Nü Kua kneaded yellow earth and fashioned human beings. Though she worked feverishly, she did not have enough strength to finish her task, so she drew her cord in a furrow through the mud and lifted it out to make human beings. That is why rich aristocrats are the human beings made from yellow earth, while ordinary poor commoners are the human beings made from the cord's furrow.

Birrell identifies two worldwide mythic motifs in Ying Shao's account. Myths commonly say the first humans were created from clay, dirt, soil, or bone; Nüwa used mud and loess. Myths widely refer to social stratification; Nüwa created the rich from loess and the poor from mud. In contrast, the builder's cord motif is uniquely Chinese and iconographic of the Goddess. In Han iconography, Nüwa sometimes holds a builder's compass.

The 9th-century Duyi Zhi (獨異志, "A Treatise on Extraordinary Things") by Li Rong records a later tradition that Nüwa and her brother Fuxi were the first humans. In this version, the goddess has been demoted from "primal creatrix to a mortal subservient to God in Heaven" and a "lowly female subservient to the male, in the traditional manner of marital relations."

Long ago, when the world first began, there were two people, Nü Kua and her older brother. They lived on Mount K'un-lun. And there were not yet any ordinary people in the world. They talked about becoming husband and wife, but they felt ashamed. So the brother at once went with his sister up Mount K'un-lun and made this prayer: "Oh Heaven, if Thou wouldst send us two forth as man and wife, then make all the misty vapor gather. If not, then make all the misty vapor disperse." At this, the misty vapor immediately gathered. When the sister became intimate with her brother, they plaited some grass to make a fan to screen their faces. Even today, when a man takes a wife, they hold a fan, which is a symbol of what happened long ago.

Pangu

One of the most popular creation myths in Chinese mythology describes the first-born semidivine human Pangu (盤古, "Coiled Antiquity") separating the world egg-like Hundun (混沌, "primordial chaos") into Heaven and Earth. However, none of the ancient Chinese classics mentions the Pangu myth, which was first recorded in the 3rd-century Sanwu Liji (三五歴記, "Historical Records of the Three Sovereign Divinities and the Five Gods"), attributed to the Three Kingdoms period Taoist author Xu Zheng. Thus, in classical Chinese mythology, Nüwa predates Pangu by six centuries.

Heaven and earth were in chaos like a chicken's egg, and Pangu was born in the middle of it. In eighteen thousand years Heaven and the earth opened and unfolded. The limpid that was Yang became the heavens, the turbid that was Yin became the earth. Pangu lived within them, and in one day he went through nine transformations, becoming more divine than Heaven and wiser than earth. Each day the heavens rose ten feet higher, each day the earth grew ten feet thicker, and each day Pangu grew ten feet taller. And so it was that in eighteen thousand years the heavens reached their fullest height, earth reached its lowest depth, and Pangu became fully grown. Afterwards, there was the Three Sovereign Divinities. Numbers began with one, were established with three, perfected by five, multiplied with seven, and fixed with nine. That is why Heaven is ninety thousand leagues from earth.

Like the Sanwu Liji, the Wuyun Linian Ji (五遠歷年紀, "A Chronicle of the Five Cycles of Time") is another 3rd-century text attributed to Xu Zheng. This version details the cosmological metamorphosis of Pangu's microcosmic body into the macrocosm of the physical world.

When the firstborn, Pangu, was approaching death, his body was transformed. His breath became the wind and clouds; his voice became peals of thunder. His left eye became the sun; his right eye became the moon. His four limbs and five extremities became the four cardinal points and the five peaks. His blood and semen became water and rivers. His muscles and veins became the earth's arteries; his flesh became fields and land. His hair and beard became the stars; his bodily hair became plants and trees. His teeth and bones became metal and rock; his vital marrow became pearls and jade. His sweat and bodily fluids became streaming rain. All the mites on his body were touched by the wind and evolved into the black-haired people.

Lincoln found parallels between Pangu and the Indo-European world parent myth, such as the primeval being's flesh becoming earth and hair becoming plants.

Tianlong and Diya myths

In another myth, the children of the spiritual beings Tianlong and Diya are the first humans.

Western scholarship

Norman J. Girardot, professor of Chinese religion at Lehigh University, analyzed complications within studies of Chinese creation mythology. On the one hand,

With regard to China there is the very real problem of the extreme paucity and fragmentation of mythological accounts, an almost total absence of any coherent mythic narratives dating to the early periods of Chinese culture. This is even more true with respect to authentic cosmogonic myths, since the preserved fragments are extremely meager and in most cases are secondary accounts historicized and moralized by the redactors of the Confucian school that was emerging as the predominant classical tradition during the Former Han period.

On the other hand, there are issues with what Girardot calls the "China as a special case fallacy"; presuming that unlike "other ancient cultures more blatantly caught up in the throes of religion and myth", China did not have any creation myths, with the exception of Pangu, which was a late, and likely foreign, importation.

Girardot traces the origins of this "methodological rigidity" or "benign neglect" for the study of Chinese religion and mythology back to early 19th-century missionary scholars who sought creation myths in early Chinese texts, "the concern for the study of Chinese cosmogony on the part of the missionaries resulted in a frustration over not finding anything that resembled the Christian doctrine of a rational creator God." For instance, the missionary and translator Walter Henry Medhurst claimed Chinese religions suffered because "'no first cause' characterizes all the sects", "the Supreme, self-existent God is scarcely traceable through the entire range of their metaphysics", and the whole system of Chinese cosmogony "is founded in materialism".

This "China as a special case" theory became an article of faith among 20th-century scholars. The French sinologist Marcel Granet's influential Chinese Thought said:

it is necessary to notice the privileged place given to politics by the Chinese. For them, the history of the world does not start before the start of civilization. It does not originate by a recitation of a creation or by cosmological speculations, but with the biographies of the sage kings. The biographies of the ancient heroes of China contain numerous mythic elements; but no cosmogonic theme has entered into the literature without having undergone a transformation. All of the legends pretend to report the facts of a human history.... The predominance accorded to political preoccupation is accompanied for the Chinese by a profound repulsion for all theories of creation.

Some further examples are:

- "In contrast to other nations the Chinese have no mythological cosmogony; the oldest sources already attempt to account for creation in a scientific way."

- "It is rather striking that, aside from this one myth [concerning Pangu], China—perhaps alone among the major civilizations of antiquity—has no real story of creation. This situation is paralleled by what we find in Chinese philosophy, where, from the very start, there is a keen interest in the relationship of man to man and in the adjustment of man to the physical universe, but relatively little interest in cosmic origins."[34]

- "…the Chinese, amongst all peoples ancient and recent, primitive and modern, are apparently unique in having no creation myth; that is, they have regarded the world and man as uncreated, as constituting the central features of a spontaneously self-generating cosmos having no creator, god, ultimate cause, or will external to itself."