Some Christian Democratic political parties have advocated distributism in their economic policies.

Overview

According to distributists, property ownership is a fundamental right, and the means of production should be spread as widely as possible, rather than being centralized under the control of the state (state capitalism/state socialism), a few individuals (plutocracy), or corporations (corporatocracy). Distributism, therefore, advocates a society marked by widespread property ownership. Co-operative economist Race Mathews argues that such a system is key to bringing about a just social order.

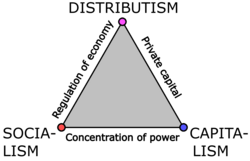

Distributism has often been described in opposition to both socialism and capitalism, which distributists see as equally flawed and exploitative.

Further, some distributists argue that socialism is the logical

conclusion of capitalism, as capitalism's concentrated powers eventually

capture the state, resulting in a form of socialism. Thomas Storck argues: "Both socialism and capitalism are products of the European Enlightenment

and are thus modernizing and anti-traditional forces. In contrast,

distributism seeks to subordinate economic activity to human life as a

whole, to our spiritual life, our intellectual life, our family life." A few distributists were influenced by the economic ideas of Proudhon and his mutualist economic theory, thus the lesser-known anarchist branch of distributism of Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker Movement could be considered a form of free-market libertarian socialism due to their opposition to both state capitalism and state socialism.

Some have seen it more as an aspiration, which has been

successfully realised in the short term by commitment to the principles

of subsidiarity and solidarity (these being built into financially independent local cooperatives and small family businesses), though proponents also cite such periods as the Middle Ages as examples of the historical long-term viability of distributism. Particularly influential in the development of distributist theory were Catholic authors G. K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc, the Chesterbelloc, two of distributism's earliest and strongest proponents.

Background

The mid-to-late 19th century witnessed an increase in popularity of political Catholicism across Europe. According to historian Michael A. Riff, a common feature of these movements was opposition not only to secularism, but also to both capitalism and socialism. In 1891 Pope Leo XIII promulgated Rerum novarum,

in which he addressed the "misery and wretchedness pressing so unjustly

on the majority of the working class" and spoke of how "a small number

of very rich men" had been able to "lay upon the teeming masses of the

laboring poor a yoke little better than that of slavery itself". Affirmed in the encyclical was the right of all men to own property, the necessity of a system that allowed "as many as possible of the people to become owners", the duty of employers to provide safe working conditions and sufficient wages, and the right of workers to unionize. Common and government property ownership was expressly dismissed as a means of helping the poor.

Around the start of the 20th century, G. K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc drew together the disparate experiences of the various cooperatives and friendly societies

in Northern England, Ireland, and Northern Europe into a coherent

political ideology which specifically advocated widespread private

ownership of housing and control of industry through owner-operated

small businesses and worker-controlled cooperatives. In the United

States in the 1930s, distributism was treated in numerous essays by

Chesterton, Belloc and others in The American Review, published and edited by Seward Collins. Pivotal among Belloc's and Chesterton's other works regarding distributism are The Servile State, and Outline of Sanity.

Although a majority of distributism's later supporters were not Catholics and many were in fact former radical socialists who had become disillusioned with socialism, distributist thought was adopted by the Catholic Worker Movement, conjoining it with the thought of Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin concerning localized and independent communities. It also influenced the thought behind the Antigonish Movement, which implemented cooperatives and other measures to aid the poor in the Canadian Maritimes. Its practical implementation in the form of local cooperatives has been documented by Race Mathews in his 1999 book Jobs of Our Own: Building a Stakeholder Society.

Position within the political spectrum

Distributism is more than a compromise between socialism and capitalism.

William Cobbett's social views influenced Chesterton.

The position of distributists when compared to other political philosophies is somewhat paradoxical and complicated. Strongly entrenched in an organic but very English Catholicism, advocating culturally traditionalist and agrarian values, directly challenging the precepts of Whig history—Belloc

was nonetheless an MP for the Liberal Party and Chesterton once stated

"As much as I ever did, more than I ever did, I believe in Liberalism.

But there was a rosy time of innocence when I believed in Liberals." This liberalism is different from most modern forms, taking influence from William Cobbett and John Ruskin, who combined elements of radicalism,

challenging the establishment position, but from a perspective of

renovation, not revolution; seeing themselves as trying to restore the

traditional liberties of England and her people which had been taken

away from them, amongst other things, since the Industrial Revolution.

While converging with certain elements of traditional Toryism, especially an appreciation of the Middle Ages

and organic society, there were several points of significant

contention. While many Tories were strongly opposed to reform, the

distributists in certain cases saw this not as conserving a legitimate

traditional concept of England, but in many cases, entrenching harmful

errors and innovations. Belloc was quite explicit in his opposition to Protestantism as a concept and schism from the Catholic Church in general, considering the division of Christendom

in the 16th century one of the most harmful events in European history.

Elements of Toryism on the other hand were quite intransigent when it

came to the Church of England as the established church, some even spurning their original legitimist ultra-royalist principles in regards to James II to uphold it.

Much of Dorothy L. Sayers'

writings on social and economic matters has affinity with distributism.

She may have been influenced by them, or have come to similar

conclusions on her own; as an Anglican, the reasonings she gave are rooted in the theologies of Creation and Incarnation, and thus are slightly different from the Catholic Chesterton and Belloc.

Economic theory

Private property

Self-portrait of G. K. Chesterton based on the distributist slogan "Three acres and a cow".

Under such a system, most people would be able to earn a living without having to rely on the use of the property

of others to do so. Examples of people earning a living in this way

would be farmers who own their own land and related machinery,

carpenters and plumbers who own their own tools, etc. The "cooperative"

approach advances beyond this perspective to recognize that such

property and equipment may be "co-owned" by local communities larger

than a family, e.g., partners in a business.

In Rerum novarum, Leo XIII states that people are likely

to work harder and with greater commitment if they themselves possess

the land on which they labor, which in turn will benefit them and their

families, as workers will be able to provide for themselves and their

household. He puts forward the idea that when men have the opportunity

to possess property and work on it, they will "learn to love the very

soil which yields in response to the labor of their hands, not only food

to eat, but an abundance of the good things for themselves and those

that are dear to them". He states also that owning property is not only beneficial for a person

and their family, but is in fact a right, due to God having "...given

the earth for the use and enjoyment of the whole human race".

Similar views are presented by G. K. Chesterton in his 1910 book What’s Wrong with the World.

Chesterton believes that whilst God has limitless capabilities, man

has limited abilities in terms of creation. As such, man therefore is

entitled to own property and to treat it as he sees fit. He states

"Property is merely the art of the democracy. It means that every man

should have something that he can shape in his own image, as he is

shaped in the image of heaven. But because he is not God, but only a

graven image of God, his self-expression must deal with limits; properly

with limits that are strict and even small." Chesterton summed up his distributist views in the phrase "Three acres and a cow".

According to Belloc, the distributive state (the state which has

implemented distributism) contains "an agglomeration of families of

varying wealth, but by far the greater number of owners of the means of

production". This broader distribution does not extend to all property,

but only to productive property; that is, that property which produces

wealth, namely, the things needed for man to survive. It includes land,

tools, and so on. Distributism allows for society to have public goods such as parks and transit systems.

Guild system

The kind of economic order envisaged by the early distributist thinkers would involve the return to some sort of guild system. The present existence of labor unions does not constitute a realization of this facet of distributist economic order, as labour unions are organized along class lines to promote class interests and frequently class struggle,

whereas guilds are mixed class syndicates composed of both employers

and employees cooperating for mutual benefit, thereby promoting class collaboration.

Banks

Distributism favors the dissolution of the current private bank system, or more specifically its profit-making basis in charging interest. Dorothy Day, for example, suggested abolishing legal enforcement of interest-rate contracts (usury). It would not entail nationalization but could involve government involvement of some sort. Distributists look favorably on credit unions as a preferable alternative to banks.

Anti-trust legislation

Distributism appears to have one of its greatest influences in anti-trust legislation

in America and Europe designed to break up monopolies and excessive

concentration of market power in one or only a few companies, trusts, interests, or cartels.

Embodying the philosophy explained by Chesterton, above, that too much

capitalism means too few capitalists, not too many, America's extensive

system of anti-trust legislation seeks to prevent the concentration of

market power in a given industry into too few hands. Requiring that no

company gain too great a share of any market is an example of how

distributism has found its way into government policy.

The assumption behind this legislation is the idea that having

economic activity decentralized among many different industry

participants is better for the economy than having one or a few large

players in an industry. (Note that anti-trust regulation does take into

account cases when only large companies are viable because of the

nature of an industry, as in the case of natural monopolies

like electricity distribution. It also accepts that mergers and

acquisitions may improve consumer welfare; however, it generally prefers

more economic agents to fewer, as this generally improves competition.)

Social credit

Social credit is an interdisciplinary distributive philosophy developed by C. H. Douglas

(1879–1952), a British engineer, who wrote a book by that name in 1924.

It encompasses the fields of economics, political science, history,

accounting, and physics. Its policies are designed, according to

Douglas, to disperse economic and political power to individuals.

Social theory

Human family

Distributism sees the family of two parents and their child or children as the central and primary social unit

of human ordering and the principal unit of a functioning distributist

society and civilization. This unit is also the basis of a

multi-generational extended family,

which is embedded in socially as well as genetically inter-related

communities, nations, etc., and ultimately in the whole human family

past, present and future. The economic system of a society should

therefore be focused primarily on the flourishing of the family unit,

but not in isolation: at the appropriate level of family context, as is

intended in the principle of subsidiarity. Distributism reflects this

doctrine most evidently by promoting the family, rather than the

individual, as the basic type of owner; that is, distributism seeks to

ensure that most families, rather than most individuals, will be owners

of productive property. The family is, then, vitally important to the

very core of distributist thought.

Subsidiarity

Distributism puts great emphasis on the principle of subsidiarity.

This principle holds that no larger unit (whether social, economic, or

political) should perform a function which can be performed by a smaller

unit. Pope Pius XI, in Quadragesimo anno,

provided the classical statement of the principle: "Just as it is

gravely wrong to take from individuals what they can accomplish by their

own initiative and industry and give it to the community, so also it is

an injustice and at the same time a grave evil and disturbance of right

order to assign to a greater and higher association what lesser and

subordinate organizations can do."

Thus, any activity of production (which distributism holds to be the

most important part of any economy) ought to be performed by the

smallest possible unit. This helps support distributism's argument that

smaller units, families if possible, ought to be in control of the

means of production, rather than the large units typical of modern

economies.

Pope Pius XI further stated, again in Quadragesimo anno,

"every social activity ought of its very nature to furnish help to the

members of the body social, and never destroy and absorb them".

To prevent large private organizations from thus dominating the body

politic, distributism applies this principle of subsidiarity to economic

as well as to social and political action.

Social security

Distributism favors the elimination of social security on the basis that it further alienates man by making him more dependent on the Servile State. Distributists such as Dorothy Day

did not favor social security when it was introduced by the United

States government. This rejection of this new program was due to the

direct influence of the ideas of Hilaire Belloc over American Distributists.

Society of artisans

Distributism promotes a society of artisans

and culture. This is influenced by an emphasis on small business,

promotion of local culture, and favoring of small production over

capitalistic mass production.

A society of artisans promotes the distributist ideal of the

unification of capital, ownership, and production rather than what

distributism sees as an alienation of man from work.

This does not, however, suggest that distributism necessarily favors a technological regression to a pre-Industrial Revolution

lifestyle, but a more local ownership of factories and other industrial

centers. Products such as food and clothing would be preferably

returned to local producers and artisans instead of being mass-produced

overseas.

Geopolitical theory

Political order

Distributism does not favor one political order over another (political accidentalism). While some distributists, such as Dorothy Day, have been anarchists,

it should be remembered that most Chestertonian distributists are

opposed to the mere concept of anarchism. Chesterton thought that

Distributism would benefit from the discipline that theoretical analysis

imposes, and that distributism is best seen as a widely encompassing

concept inside of which any number of interpretations and perspectives

can fit. This concept should fit in a political system broadly

characterized by widespread ownership of productive property.

Political parties

The Brazilian political party, Humanist Party of Solidarity is a distributist party, and distributism has influenced Christian Democratic parties in Continental Europe and the Democratic Labor Party in Australia. Ross Douthat and Reihan Salam view their Grand New Party, a roadmap for revising the Republican Party in the United States, as "a book written in the distributist tradition".

War

Distributists usually use Just War Theory

in determining whether a war should be fought or not. Historical

positions of distributist thinkers provide insight into a distributist

position on war. Both Belloc and Chesterton opposed British imperialism

in general, as well as specifically opposing the Second Boer War, but supported British involvement in World War I.

On the other hand, prominent distributists such as Dorothy Day

and those involved in the Catholic Worker Movement were/are strict pacifists, even to the point of condemning involvement in World War II at much personal cost.

Influence

E. F. Schumacher

Distributism is known to have had an influence on the economist E. F. Schumacher, a convert to Catholicism.

Mondragon Corporation

The Mondragon Corporation, based in the Basque Country in a region of Spain and France, was founded by a Catholic priest, Father José María Arizmendiarrieta, who seems to have been influenced by the same Catholic social and economic teachings that inspired Belloc, Chesterton, Father Vincent McNabb, and the other founders of distributism.

Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic

Distributist ideas were put into practice by The Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic, a group of artists and craftsmen who established a community in Ditchling,

Sussex, England, in 1920, with the motto "Men rich in virtue studying

beautifulness living in peace in their houses". The Guild sought to

recreate an idealized medieval lifestyle in the manner of the Arts and Crafts Movement; it survived almost 70 years, until 1989.

Big Society

The Big Society was the flagship policy idea of the 2010 UK Conservative Party general election manifesto.

Some distributists claim that the rhetorical marketing of this policy

was influenced by aphorisms of the distributist ideology and promotes

distributism. It purportedly formed a part of the legislative program of the Conservative – Liberal Democrat Coalition Agreement.

The stated aim was "to create a climate that empowers local people and

communities, building a big society that will 'take power away from

politicians and give it to people.'" The idea of the Big Society was suggested by Steve Hilton,

who worked as director of strategy for David Cameron during the

Coalition government before moving on to live and work in California.