Graduation ceremony on Convocation day at the University of Oxford. The Pro-Vice-Chancellor in MA gown and hood, Proctor in official dress and new Doctors of Philosophy in scarlet full dress. Behind them, a bedel, a Doctor and Bachelors of Arts and Medicine graduate.

A university (Latin: universitas, 'a whole') is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in various academic disciplines. Universities typically provide undergraduate education and postgraduate education.

The word university is derived from the Latin universitas magistrorum et scholarium, which roughly means "community of teachers and scholars". While antecedents had existed in Asia and Africa, the modern university system has roots in the European medieval university, which was created in Italy and evolved from cathedral schools for the clergy during the High Middle Ages.

History

Definition

The original Latin word universitas refers in general to "a number of persons associated into one body, a society, company, community, guild, corporation, etc". At the time of the emergence of urban town life and medieval guilds, specialized "associations of students and teachers

with collective legal rights usually guaranteed by charters issued by

princes, prelates, or the towns in which they were located" came to be

denominated by this general term. Like other guilds, they were

self-regulating and determined the qualifications of their members.

In modern usage the word has come to mean "An institution of

higher education offering tuition in mainly non-vocational subjects and

typically having the power to confer degrees," with the earlier emphasis on its corporate organization considered as applying historically to Medieval universities.

The original Latin word referred to degree-awarding institutions of learning in Western and Central Europe, where this form of legal organisation was prevalent and from where the institution spread around the world.

Academic freedom

An important idea in the definition of a university is the notion of academic freedom. The first documentary evidence of this comes from early in the life of the University of Bologna, which adopted an academic charter, the Constitutio Habita, in 1158 or 1155,

which guaranteed the right of a traveling scholar to unhindered passage

in the interests of education. Today this is claimed as the origin of

"academic freedom". This is now widely recognised internationally - on 18 September 1988, 430 university rectors signed the Magna Charta Universitatum, marking the 900th anniversary of Bologna's foundation. The number of universities signing the Magna Charta Universitatum continues to grow, drawing from all parts of the world.

Antecedents

According to Encyclopædia Britannica, the earliest universities were founded in Asia and Africa, predating the first European medieval universities. The University of Al Quaraouiyine, founded in Morocco by Fatima al-Fihri in 859, is considered by some to be the oldest degree-granting university.

Their endowment by a prince or monarch and their role in training government officials made early Mediterranean universities similar to Islamic madrasas,

although madrasas were generally smaller, and individual teachers,

rather than the madrasa itself, granted the license or degree. Scholars like Arnold H. Green and Hossein Nasr have argued that starting in the 10th century, some medieval Islamic madrasas became universities. However, scholars like George Makdisi, Toby Huff and Norman Daniel argue that the European university has no parallel in the medieval Islamic world. Several other scholars consider the university as uniquely European in origin and characteristics. Darleen Pryds questions this view, pointing out that madaris

and European universities in the Mediterranean region shared similar

foundations by princely patrons and were intended to provide loyal

administrators to further the rulers' agenda.

Some scholars, including Makdisi, have argued that early medieval universities were influenced by the madrasas in Al-Andalus, the Emirate of Sicily, and the Middle East during the Crusades. Norman Daniel, however, views this argument as overstated.

Roy Lowe and Yoshihito Yasuhara have recently drawn on the

well-documented influences of scholarship from the Islamic world on the

universities of Western Europe to call for a reconsideration of the

development of higher education, turning away from a concern with local

institutional structures to a broader consideration within a global

context.

Medieval universities

The University of Bologna in Italy, founded in 1088, is the oldest university, the word university (Latin: universitas) having been coined at its foundation.

The university is generally regarded as a formal institution that has its origin in the Medieval Christian tradition. European higher education took place for hundreds of years in cathedral schools or monastic schools (scholae monasticae), in which monks and nuns taught classes; evidence of these immediate forerunners of the later university at many places dates back to the 6th century. The earliest universities were developed under the aegis of the Latin Church by papal bull as studia generalia

and perhaps from cathedral schools. It is possible, however, that the

development of cathedral schools into universities was quite rare, with

the University of Paris being an exception. Later they were also founded by Kings (University of Naples Federico II, Charles University in Prague, Jagiellonian University in Kraków) or municipal administrations (University of Cologne, University of Erfurt). In the early medieval period,

most new universities were founded from pre-existing schools, usually

when these schools were deemed to have become primarily sites of higher

education. Many historians state that universities and cathedral schools

were a continuation of the interest in learning promoted by The residence of a religious community. Pope Gregory VII was critical in promoting and regulating the concept of modern university as his 1079 Papal Decree ordered the regulated establishment of cathedral schools that transformed themselves into the first European universities.

The first universities in Europe with a form of corporate/guild structure were the University of Bologna (1088), the University of Paris (c.1150, later associated with the Sorbonne), and the University of Oxford (1167).

The University of Bologna began as a law school teaching the ius gentium or Roman law

of peoples which was in demand across Europe for those defending the

right of incipient nations against empire and church. Bologna's special

claim to Alma Mater Studiorum

is based on its autonomy, its awarding of degrees, and other structural

arrangements, making it the oldest continuously operating institution independent of kings, emperors or any kind of direct religious authority.

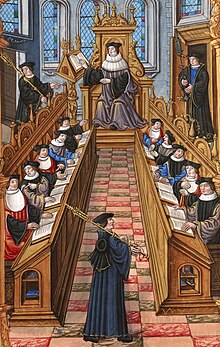

Meeting of doctors at the University of Paris. From a medieval manuscript.

The conventional date of 1088, or 1087 according to some, records when Irnerius commences teaching Emperor Justinian's 6th century codification of Roman law, the Corpus Iuris Civilis,

recently discovered at Pisa. Lay students arrived in the city from many

lands entering into a contract to gain this knowledge, organising

themselves into 'Nationes', divided between that of the Cismontanes and

that of the Ultramontanes. The students "had all the power … and

dominated the masters".

In Europe, young men proceeded to university when they had completed their study of the trivium–the preparatory arts of grammar, rhetoric and dialectic or logic–and the quadrivium: arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy.

All over Europe rulers and city governments began to create

universities to satisfy a European thirst for knowledge, and the belief

that society would benefit from the scholarly expertise generated from

these institutions. Princes and leaders of city governments perceived

the potential benefits of having a scholarly expertise develop with the

ability to address difficult problems and achieve desired ends. The

emergence of humanism was essential to this understanding of the

possible utility of universities as well as the revival of interest in

knowledge gained from ancient Greek texts.

The rediscovery of Aristotle's

works–more than 3000 pages of it would eventually be translated–fuelled

a spirit of inquiry into natural processes that had already begun to

emerge in the 12th century. Some scholars believe that these works

represented one of the most important document discoveries in Western

intellectual history. Richard Dales, for instance, calls the discovery of Aristotle's works "a turning point in the history of Western thought."

After Aristotle re-emerged, a community of scholars, primarily

communicating in Latin, accelerated the process and practice of

attempting to reconcile the thoughts of Greek antiquity, and especially

ideas related to understanding the natural world, with those of the

church. The efforts of this "scholasticism"

were focused on applying Aristotelian logic and thoughts about natural

processes to biblical passages and attempting to prove the viability of

those passages through reason. This became the primary mission of

lecturers, and the expectation of students.

Heidelberg University is the oldest university in Germany and among Europe's best ranked. It was established in 1386.

The university culture developed differently in northern Europe than

it did in the south, although the northern (primarily Germany, France

and Great Britain)

and southern universities (primarily Italy) did have many elements in

common. Latin was the language of the university, used for all texts,

lectures, disputations and examinations. Professors lectured on the books of Aristotle for logic, natural philosophy, and metaphysics; while Hippocrates, Galen, and Avicenna

were used for medicine. Outside of these commonalities, great

differences separated north and south, primarily in subject matter.

Italian universities focused on law and medicine, while the northern

universities focused on the arts and theology. There were distinct

differences in the quality of instruction in these areas which were

congruent with their focus, so scholars would travel north or south

based on their interests and means. There was also a difference in the

types of degrees awarded at these universities. English, French and

German universities usually awarded bachelor's degrees, with the

exception of degrees in theology, for which the doctorate was more

common. Italian universities awarded primarily doctorates. The

distinction can be attributed to the intent of the degree holder after

graduation – in the north the focus tended to be on acquiring teaching

positions, while in the south students often went on to professional

positions. The structure of northern universities tended to be modeled after the system of faculty governance developed at the University of Paris. Southern universities tended to be patterned after the student-controlled model begun at the University of Bologna.

Among the southern universities, a further distinction has been noted

between those of northern Italy, which followed the pattern of Bologna

as a "self-regulating, independent corporation of scholars" and those of

southern Italy and Iberia, which were "founded by royal and imperial

charter to serve the needs of government."

Early modern universities

During the Early Modern period

(approximately late 15th century to 1800), the universities of Europe

would see a tremendous amount of growth, productivity and innovative

research. At the end of the Middle Ages, about 400 years after the first

European university was founded, there were twenty-nine universities

spread throughout Europe. In the 15th century, twenty-eight new ones

were created, with another eighteen added between 1500 and 1625.

This pace continued until by the end of the 18th century there were

approximately 143 universities in Europe, with the highest

concentrations in the German Empire (34), Italian countries (26), France

(25), and Spain (23) – this was close to a 500% increase over the

number of universities toward the end of the Middle Ages. This number

does not include the numerous universities that disappeared, or

institutions that merged with other universities during this time.

The identification of a university was not necessarily obvious during

the Early Modern period, as the term is applied to a burgeoning number

of institutions. In fact, the term "university" was not always used to

designate a higher education institution. In Mediterranean countries, the term studium generale was still often used, while "Academy" was common in Northern European countries.

The University of Basel is Switzerland's oldest university (1460) and through the heritage of Erasmus counted among the birth places of Renaissance humanism

17th century classroom at the University of Salamanca

The propagation of universities was not necessarily a steady

progression, as the 17th century was rife with events that adversely

affected university expansion. Many wars, and especially the Thirty Years' War, disrupted the university landscape throughout Europe at different times. War, plague, famine, regicide,

and changes in religious power and structure often adversely affected

the societies that provided support for universities. Internal strife

within the universities themselves, such as student brawling and

absentee professors, acted to destabilize these institutions as well.

Universities were also reluctant to give up older curricula, and the

continued reliance on the works of Aristotle defied contemporary

advancements in science and the arts. This era was also affected by the rise of the nation-state.

As universities increasingly came under state control, or formed under

the auspices of the state, the faculty governance model (begun by the

University of Paris) became more and more prominent. Although the older

student-controlled universities still existed, they slowly started to

move toward this structural organization. Control of universities still

tended to be independent, although university leadership was

increasingly appointed by the state.

Although the structural model provided by the University of

Paris, where student members are controlled by faculty "masters",

provided a standard for universities, the application of this model took

at least three different forms. There were universities that had a

system of faculties whose teaching addressed a very specific curriculum;

this model tended to train specialists. There was a collegiate or

tutorial model based on the system at University of Oxford

where teaching and organization was decentralized and knowledge was

more of a generalist nature. There were also universities that combined

these models, using the collegiate model but having a centralized

organization.

Early Modern universities initially continued the curriculum and research of the Middle Ages: natural philosophy, logic, medicine, theology, mathematics, astronomy, astrology, law, grammar and rhetoric.

Aristotle was prevalent throughout the curriculum, while medicine also

depended on Galen and Arabic scholarship. The importance of humanism for

changing this state-of-affairs cannot be underestimated. Once humanist professors joined the university faculty, they began to transform the study of grammar and rhetoric through the studia humanitatis.

Humanist professors focused on the ability of students to write and

speak with distinction, to translate and interpret classical texts, and

to live honorable lives.

Other scholars within the university were affected by the humanist

approaches to learning and their linguistic expertise in relation to

ancient texts, as well as the ideology that advocated the ultimate

importance of those texts. Professors of medicine such as Niccolò Leoniceno, Thomas Linacre

and William Cop were often trained in and taught from a humanist

perspective as well as translated important ancient medical texts. The

critical mindset imparted by humanism was imperative for changes in

universities and scholarship. For instance, Andreas Vesalius

was educated in a humanist fashion before producing a translation of

Galen, whose ideas he verified through his own dissections. In law,

Andreas Alciatus infused the Corpus Juris with a humanist perspective, while Jacques Cujas humanist writings were paramount to his reputation as a jurist. Philipp Melanchthon cited the works of Erasmus

as a highly influential guide for connecting theology back to original

texts, which was important for the reform at Protestant universities. Galileo Galilei, who taught at the Universities of Pisa and Padua, and Martin Luther, who taught at the University of Wittenberg

(as did Melanchthon), also had humanist training. The task of the

humanists was to slowly permeate the university; to increase the

humanist presence in professorships and chairs, syllabi and textbooks so

that published works would demonstrate the humanistic ideal of science

and scholarship.

Although the initial focus of the humanist scholars in the

university was the discovery, exposition and insertion of ancient texts

and languages into the university, and the ideas of those texts into

society generally, their influence was ultimately quite progressive. The

emergence of classical texts brought new ideas and led to a more

creative university climate (as the notable list of scholars above

attests to). A focus on knowledge coming from self, from the human, has a

direct implication for new forms of scholarship and instruction, and

was the foundation for what is commonly known as the humanities. This

disposition toward knowledge manifested in not simply the translation

and propagation of ancient texts, but also their adaptation and

expansion. For instance, Vesalius was imperative for advocating the use

of Galen, but he also invigorated this text with experimentation,

disagreements and further research.

The propagation of these texts, especially within the universities, was

greatly aided by the emergence of the printing press and the beginning

of the use of the vernacular, which allowed for the printing of

relatively large texts at reasonable prices.

Examining the influence of humanism on scholars in medicine,

mathematics, astronomy and physics may suggest that humanism and

universities were a strong impetus for the scientific revolution.

Although the connection between humanism and the scientific discovery

may very well have begun within the confines of the university, the

connection has been commonly perceived as having been severed by the

changing nature of science during the Scientific Revolution. Historians such as Richard S. Westfall

have argued that the overt traditionalism of universities inhibited

attempts to re-conceptualize nature and knowledge and caused an

indelible tension between universities and scientists.

This resistance to changes in science may have been a significant

factor in driving many scientists away from the university and toward

private benefactors, usually in princely courts, and associations with

newly forming scientific societies.

Other historians find incongruity in the proposition that the

very place where the vast number of the scholars that influenced the

scientific revolution received their education should also be the place

that inhibits their research and the advancement of science. In fact,

more than 80% of the European scientists between 1450–1650 included in

the Dictionary of Scientific Biography were university trained, of which approximately 45% held university posts.

It was the case that the academic foundations remaining from the Middle

Ages were stable, and they did provide for an environment that fostered

considerable growth and development. There was considerable reluctance

on the part of universities to relinquish the symmetry and

comprehensiveness provided by the Aristotelian system, which was

effective as a coherent system for understanding and interpreting the

world. However, university professors still utilized some autonomy, at

least in the sciences, to choose epistemological foundations and

methods. For instance, Melanchthon and his disciples at University of

Wittenberg were instrumental for integrating Copernican mathematical

constructs into astronomical debate and instruction.

Another example was the short-lived but fairly rapid adoption of

Cartesian epistemology and methodology in European universities, and the

debates surrounding that adoption, which led to more mechanistic

approaches to scientific problems as well as demonstrated an openness to

change. There are many examples which belie the commonly perceived

intransigence of universities.

Although universities may have been slow to accept new sciences and

methodologies as they emerged, when they did accept new ideas it helped

to convey legitimacy and respectability, and supported the scientific

changes through providing a stable environment for instruction and

material resources.

Regardless of the way the tension between universities,

individual scientists, and the scientific revolution itself is

perceived, there was a discernible impact on the way that university

education was constructed. Aristotelian epistemology provided a coherent

framework not simply for knowledge and knowledge construction, but also

for the training of scholars within the higher education setting. The

creation of new scientific constructs during the scientific revolution,

and the epistemological challenges that were inherent within this

creation, initiated the idea of both the autonomy of science and the

hierarchy of the disciplines. Instead of entering higher education to

become a "general scholar" immersed in becoming proficient in the entire

curriculum, there emerged a type of scholar that put science first and

viewed it as a vocation in itself. The divergence between those focused

on science and those still entrenched in the idea of a general scholar

exacerbated the epistemological tensions that were already beginning to

emerge.

The epistemological tensions between scientists and universities

were also heightened by the economic realities of research during this

time, as individual scientists, associations and universities were vying

for limited resources. There was also competition from the formation of

new colleges funded by private benefactors and designed to provide free

education to the public, or established by local governments to provide

a knowledge hungry populace with an alternative to traditional

universities.

Even when universities supported new scientific endeavors, and the

university provided foundational training and authority for the research

and conclusions, they could not compete with the resources available

through private benefactors.

Universities in northern Europe were more willing to accept the ideas of Enlightenment and were often greatly influenced by them. For instance the historical ensemble of the University of Tartu in Estonia, that was erected around that time, is now included into European Heritage Label list as an example of a university in the Age of Enlightenment

By the end of the early modern period, the structure and orientation

of higher education had changed in ways that are eminently recognizable

for the modern context. Aristotle was no longer a force providing the

epistemological and methodological focus for universities and a more

mechanistic orientation was emerging. The hierarchical place of

theological knowledge had for the most part been displaced and the

humanities had become a fixture, and a new openness was beginning to

take hold in the construction and dissemination of knowledge that were

to become imperative for the formation of the modern state.

Modern universities

King's College London, established by Royal Charter having been founded by King George IV and Duke of Wellington in 1829, is one of the founding colleges of the University of London.

Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, a German technical university, founded in the 19th century

By the 18th century, universities published their own research journals

and by the 19th century, the German and the French university models

had arisen. The German, or Humboldtian model, was conceived by Wilhelm von Humboldt and based on Friedrich Schleiermacher's liberal ideas pertaining to the importance of freedom, seminars, and laboratories in universities. The French university model involved strict discipline and control over every aspect of the university.

Until the 19th century, religion

played a significant role in university curriculum; however, the role

of religion in research universities decreased in the 19th century, and

by the end of the 19th century, the German university model had spread

around the world. Universities concentrated on science in the 19th and

20th centuries and became increasingly accessible to the masses. In the

United States, the Johns Hopkins University was the first to adopt the (German) research university model; this pioneered the adoption by most other American universities. In Britain, the move from Industrial Revolution to modernity saw the arrival of new civic universities with an emphasis on science and engineering, a movement initiated in 1960 by Sir Keith Murray (chairman of the University Grants Committee) and Sir Samuel Curran, with the formation of the University of Strathclyde. The British also established universities worldwide, and higher education became available to the masses not only in Europe.

In 1963, the Robbins Report

on universities in the United Kingdom concluded that such institutions

should have four main "objectives essential to any properly balanced

system: instruction in skills; the promotion of the general powers of

the mind so as to produce not mere specialists but rather cultivated men

and women; to maintain research in balance with teaching, since

teaching should not be separated from the advancement of learning and

the search for truth; and to transmit a common culture and common

standards of citizenship."

In the early 21st century, concerns were raised over the

increasing managerialisation and standardisation of universities

worldwide. Neo-liberal management models have in this sense been

critiqued for creating "corporate universities (where) power is

transferred from faculty to managers, economic justifications dominate,

and the familiar 'bottom line' ecclipses pedagogical or intellectual

concerns".

Academics' understanding of time, pedagogical pleasure, vocation, and

collegiality have been cited as possible ways of alleviating such

problems.

National universities

A national university

is generally a university created or run by a national state but at the

same time represents a state autonomic institution which functions as a

completely independent body inside of the same state. Some national

universities are closely associated with national cultural, religious or political aspirations, for instance the National University of Ireland, which formed partly from the Catholic University of Ireland

which was created almost immediately and specifically in answer to the

non-denominational universities which had been set up in Ireland in

1850. In the years leading up to the Easter Rising, and in no small part a result of the Gaelic Romantic revivalists, the NUI collected a large amount of information on the Irish language and Irish culture. Reforms in Argentina were the result of the University Revolution of 1918 and its posterior reforms by incorporating values that sought for a more equal higher education system.

Intergovernmental universities

Campus universities with most buildings clustered closely together became especially widespread since the 19th century (Cornell University)

Universities created by bilateral or multilateral treaties between states are intergovernmental. An example is the Academy of European Law, which offers training in European law to lawyers, judges, barristers, solicitors, in-house counsel and academics. EUCLID (Pôle Universitaire Euclide, Euclid University) is chartered as a university and umbrella organisation dedicated to sustainable development in signatory countries, and the United Nations University

engages in efforts to resolve the pressing global problems that are of

concern to the United Nations, its peoples and member states. The European University Institute,

a post-graduate university specialised in the social sciences, is

officially an intergovernmental organisation, set up by the member

states of the European Union.

Organization

The University of Sydney is Australia's oldest university.

Although each institution is organized differently, nearly all universities have a board of trustees; a president, chancellor, or rector;

at least one vice president, vice-chancellor, or vice-rector; and deans

of various divisions. Universities are generally divided into a number

of academic departments, schools or faculties. Public university

systems are ruled over by government-run higher education boards. They

review financial requests and budget proposals and then allocate funds

for each university in the system. They also approve new programs of

instruction and cancel or make changes in existing programs. In

addition, they plan for the further coordinated growth and development

of the various institutions of higher education in the state or country.

However, many public universities in the world have a considerable

degree of financial, research and pedagogical autonomy. Private universities

are privately funded and generally have broader independence from state

policies. However, they may have less independence from business

corporations depending on the source of their finances.

Around the world

The funding and organization of universities varies widely between

different countries around the world. In some countries universities are

predominantly funded by the state, while in others funding may come

from donors or from fees which students attending the university must

pay. In some countries the vast majority of students attend university

in their local town, while in other countries universities attract

students from all over the world, and may provide university

accommodation for their students.

Classification

The definition of a university varies widely, even within some

countries. Where there is clarification, it is usually set by a

government agency. For example:

In Australia, the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency

(TEQSA) is Australia's independent national regulator of the higher

education sector. Students rights within university are also protected

by the Education Services for Overseas Students Act (ESOS).

In the United States there is no nationally standardized definition for the term university, although the term has traditionally been used to designate research institutions and was once reserved for doctorate-granting research institutions. Some states, such as Massachusetts, will only grant a school "university status" if it grants at least two doctoral degrees.

In the United Kingdom, the Privy Council is responsible for approving the use of the word university in the name of an institution, under the terms of the Further and Higher Education Act 1992.

In India, a new designation deemed universities

has been created for institutions of higher education that are not

universities, but work at a very high standard in a specific area of

study ("An Institution of Higher Education, other than universities,

working at a very high standard in specific area of study, can be

declared by the Central Government on the advice of the University Grants Commission

as an Institution 'Deemed-to-be-university'"). Institutions that are

'deemed-to-be-university' enjoy the academic status and the privileges

of a university.

Through this provision many schools that are commercial in nature and

have been established just to exploit the demand for higher education

have sprung up.

In Canada, college generally refers to a two-year, non-degree-granting institution, while university connotes a four-year, degree-granting institution. Universities may be sub-classified (as in the Macleans rankings) into large research universities with many PhD-granting programs and medical schools (for example, McGill University); "comprehensive" universities that have some PhDs but are not geared toward research (such as Waterloo); and smaller, primarily undergraduate universities (such as St. Francis Xavier).

In Germany, universities are institutions of higher education

which have the power to confer bachelor, master and PhD degrees. They

are explicitly recognised as such by law and cannot be founded without

government approval. The term Universitaet (i.e. the German term for

university) is protected by law and any use without official approval is

a criminal offense. Most of them are public institutions, though a few

private universities exist. Such universities are always research

universities. Apart from these universities, Germany has other

institutions of higher education (Hochschule, Fachhochschule). Fachhochschule means a higher education institution which is similar to the former polytechnics

in the British education system, the English term used for these German

institutions is usually 'university of applied sciences'. They can

confer master degrees but no PhDs. They are similar to the model of teaching universities

with less research and the research undertaken being highly practical.

Hochschule can refer to various kinds of institutions, often specialised

in a certain field (e.g. music, fine arts, business). They might or

might not have the power to award PhD degrees, depending on the

respective government legislation. If they award PhD degrees, their rank

is considered equivalent to that of universities proper (Universitaet),

if not, their rank is equivalent to universities of applied sciences.

Colloquial usage

Colloquially, the term university may be used to describe a phase in one's life: "When I was at university..." (in the United States and Ireland, college

is often used instead: "When I was in college..."). In Ireland,

Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Nigeria, the

Netherlands, Italy, Spain and the German-speaking countries, university is often contracted to uni.

In Ghana, New Zealand, Bangladesh and in South Africa it is sometimes

called "varsity" (although this has become uncommon in New Zealand in

recent years). "Varsity" was also common usage in the UK in the 19th

century. "Varsity" is still in common usage in Scotland.

Cost

Comenius University in Bratislava - the largest public university in Slovakia

University of Helsinki, the oldest and largest public university in Finland, founded in 1640.

In many countries, students are required to pay tuition fees.

Many students look to get 'student grants' to cover the cost of

university. In 2016, the average outstanding student loan balance per

borrower in the United States was US$30,000.

In many U.S. states, costs are anticipated to rise for students as a

result of decreased state funding given to public universities.

There are several major exceptions on tuition fees. In many

European countries, it is possible to study without tuition fees. Public

universities in Nordic countries

were entirely without tuition fees until around 2005. Denmark, Sweden

and Finland then moved to put in place tuition fees for foreign

students. Citizens of EU

and EEA member states and citizens from Switzerland remain exempted

from tuition fees, and the amounts of public grants granted to promising

foreign students were increased to offset some of the impact.

The situation in Germany is similar; public universities usually do not

charge tuition fees apart from a small administrative fee. For degrees

of a postgraduate professional level sometimes tuition fees are levied.

Private universities, however, almost always charge tuition fees.