| Hydrocephalus | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Water on the brain |

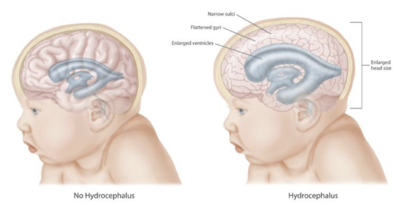

| |

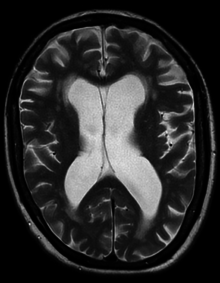

| Hydrocephalus as seen on a CT scan of the brain. The black areas in the middle of the brain (the lateral ventricles) are abnormally large and filled with fluid. | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Neurosurgery |

| Symptoms | Babies: rapid head growth, vomiting, sleepiness, seizures Older people: Headaches, double vision, poor balance, urinary incontinence, personality changes, mental impairment |

| Causes | Neural tube defects, meningitis, brain tumors, traumatic brain injury, intraventricular hemorrhage |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms and medical imaging |

| Treatment | Surgery |

| Prognosis | Variable, often normal life |

| Frequency | 1.5 per 1,000 (babies) |

Hydrocephalus is a condition in which an accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) occurs within the brain. This typically causes increased pressure inside the skull. Older people may have headaches, double vision, poor balance, urinary incontinence, personality changes, or mental impairment. In babies, it may be seen as a rapid increase in head size. Other symptoms may include vomiting, sleepiness, seizures, and downward pointing of the eyes.

Hydrocephalus can occur due to birth defects or be acquired later in life. Associated birth defects include neural tube defects and those that result in aqueductal stenosis. Other causes include meningitis, brain tumors, traumatic brain injury, intraventricular hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage. The four types of hydrocephalus are communicating, noncommunicating, ex vacuo, and normal pressure. Diagnosis is typically made by physical examination and medical imaging.

Hydrocephalus is typically treated by the surgical placement of a shunt system. A procedure called a third ventriculostomy may be an option in a few people. Complications from shunts may include overdrainage, underdrainage, mechanical failure, infection, or obstruction. This may require replacement. Outcomes are variable, but many people with shunts live normal lives. Without treatment, death or permanent disability may occur.

About one to two per 1,000 newborns have hydrocephalus. Rates in the developing world may be higher. Normal pressure hydrocephalus is estimated to affect about 5 per 100,000 people, with rates increasing with age. Description of hydrocephalus by Hippocrates dates back more than 2,000 years. The word "hydrocephalus" is from the Greek ὕδωρ, hydōr, meaning "water" and κεφαλή, kephalē, meaning "head".

Signs and symptoms

Illustration showing different effects of hydrocephalus on the brain and cranium

The clinical presentation of hydrocephalus varies with chronicity. Acute dilatation of the ventricular system

is more likely to manifest with the nonspecific signs and symptoms of

increased intracranial pressure (ICP). By contrast, chronic dilatation

(especially in the elderly population) may have a more insidious onset

presenting, for instance, with Hakim's triad (Adams' triad).

Symptoms of increased ICP may include headaches, vomiting, nausea, papilledema, sleepiness, or coma. Elevated ICP may result in uncal or tonsillar herniation, with resulting life-threatening brain stem compression.

Hakim's triad of gait instability, urinary incontinence, and dementia is a relatively typical manifestation of the distinct entity normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Focal neurological deficits may also occur, such as abducens nerve palsy and vertical gaze palsy (Parinaud syndrome due to compression of the quadrigeminal plate, where the neural centers coordinating the conjugated vertical eye movement are located). The symptoms depend on the cause of the blockage, the person's age, and how much brain tissue has been damaged by the swelling.

In infants with hydrocephalus, CSF builds up in the central nervous system (CNS), causing the fontanelle (soft spot) to bulge and the head to be larger than expected. Early symptoms may also include:

- Eyes that appear to gaze downward

- Irritability

- Seizures

- Separated sutures

- Sleepiness

- Vomiting

Symptoms that may occur in older children can include:

- Brief, shrill, high-pitched cry

- Changes in personality, memory, or the ability to reason or think

- Changes in facial appearance and eye spacing (craniofacial disproportion)

- Crossed eyes or uncontrolled eye movements

- Difficulty feeding

- Excessive sleepiness

- Headaches

- Irritability, poor temper control

- Loss of bladder control (urinary incontinence)

- Loss of coordination and trouble walking

- Muscle spasticity (spasm)

- Slow growth (child 0–5 years)

- Delayed milestones

- Failure to thrive

- Slow or restricted movement

- Vomiting

Because hydrocephalus can injure the brain, thought and behavior may be adversely affected. Learning disabilities, including short-term memory loss,

are common among those with hydrocephalus, who tend to score better on

verbal IQ than on performance IQ, which is thought to reflect the

distribution of nerve damage to the brain.

However, the severity of hydrocephalus can differ considerably between

individuals, and some are of average or above-average intelligence.

Someone with hydrocephalus may have coordination and visual problems, or

clumsiness. They may reach puberty earlier than the average child (this

is called precocious puberty). About one in four develops epilepsy.

Cause

Congenital

A one-year-old girl with hydrocephalus showing "sunset eyes", before shunt surgery

Congenital hydrocephalus is present in the infant prior to birth, meaning the fetus developed hydrocephalus in utero during fetal development.

The most common cause of congenital hydrocephalus is aqueductal

stenosis, which occurs when the narrow passage between the third and

fourth ventricles in the brain is blocked or too narrow to allow

sufficient cerebral spinal fluid to drain. Fluid accumulates in the

upper ventricles, causing hydrocephalus.

Other causes of congenital hydrocephalus include neural-tube defects, arachnoid cysts, Dandy–Walker syndrome, and Arnold–Chiari malformation.

The cranial bones

fuse by the end of the third year of life. For head enlargement to

occur, hydrocephalus must occur before then. The causes are usually

genetic, but can also be acquired and usually occur within the first few

months of life, which include intraventricular matrix hemorrhages in premature infants, infections, type II Arnold-Chiari malformation, aqueduct atresia and stenosis, and Dandy-Walker malformation.

In newborns and toddlers with hydrocephalus, the head

circumference is enlarged rapidly and soon surpasses the 97th

percentile. Since the skull bones have not yet firmly joined together,

bulging, firm anterior and posterior fontanelles may be present even when the person is in an upright position.

The infant exhibits fretfulness, poor feeding, and frequent vomiting. As the hydrocephalus progresses, torpor

sets in, and infants show lack of interest in their surroundings. Later

on, their upper eyelids become retracted and their eyes are turned

downwards ("sunset eyes") (due to hydrocephalic pressure on the mesencephalic tegmentum and paralysis of upward gaze). Movements become weak and the arms may become tremulous. Papilledema is absent, but vision may be reduced. The head becomes so enlarged that they eventually may be bedridden.

About 80–90% of fetuses or newborn infants with spina bifida—often associated with meningocele or myelomeningocele—develop hydrocephalus.

Acquired

This condition is acquired as a consequence of CNS infections, meningitis, brain tumors, head trauma, toxoplasmosis, or intracranial hemorrhage (subarachnoid or intraparenchymal), and is usually painful.

Type

The cause of

hydrocephalus is not known with certainty and is probably

multifactorial. It may be caused by impaired CSF flow, reabsorption, or

excessive CSF production.

- Obstruction to CSF flow hinders its free passage through the ventricular system and subarachnoid space (e.g., stenosis of the cerebral aqueduct or obstruction of the interventricular foramina secondary to tumors, hemorrhages, infections or congenital malformations) and can cause increases in ICP.

- Hydrocephalus can also be caused by overproduction of CSF (relative obstruction) (e.g., choroid plexus papilloma, villous hypertrophy).

- Bilateral ureteric obstruction is a rare, but reported, cause of hydrocephalus.

Based on its underlying mechanisms, hydrocephalus can be classified

into communicating and noncommunicating (obstructive). Both forms can be

either congenital or acquired.

Communicating

Communicating

hydrocephalus, also known as nonobstructive hydrocephalus, is caused by

impaired CSF reabsorption in the absence of any obstruction of CSF flow

between the ventricles and subarachnoid space. This may be due to

functional impairment of the arachnoidal granulations (also called arachnoid granulations or Pacchioni's granulations), which are located along the superior sagittal sinus,

and is the site of CSF reabsorption back into the venous system.

Various neurologic conditions may result in communicating hydrocephalus,

including subarachnoid/intraventricular hemorrhage, meningitis, and

congenital absence of arachnoid villi. Scarring and fibrosis of the

subarachnoid space following infectious, inflammatory, or hemorrhagic

events can also prevent resorption of CSF, causing diffuse ventricular

dilatation.

Noncommunicating

Noncommunicating hydrocephalus, or obstructive hydrocephalus, is caused by a CSF-flow obstruction.

- Foramen of Monro obstruction may lead to dilation of one, or if large enough (e.g., in colloid cyst), both lateral ventricles.

- The aqueduct of Sylvius, normally narrow, may be obstructed by a number of genetic or acquired lesions (e.g., atresia, ependymitis, hemorrhage, or tumor) and lead to dilation of both lateral ventricles, as well as the third ventricle.

- Fourth ventricle obstruction leads to dilatation of the aqueduct, as well as the lateral and third ventricles (e.g., Chiari malformation).

- The foramina of Luschka and foramen of Magendie may be obstructed due to congenital malformation (e.g., Dandy-Walker malformation).

Other

Hydrocephalus ex vacuo from vascular dementia as seen on MRI

- Normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) is a particular form of chronic communicating hydrocephalus, characterized by enlarged cerebral ventricles, with only intermittently elevated cerebrospinal fluid pressure. Characteristic triad of symptoms are; dementia, apraxic gait and urinary incontinence. The diagnosis of NPH can be established only with the help of continuous intraventricular pressure recordings (over 24 hours or even longer), since more often than not instant measurements yield normal pressure values. Dynamic compliance studies may be also helpful. Altered compliance (elasticity) of the ventricular walls, as well as increased viscosity of the cerebrospinal fluid, may play a role in the pathogenesis.

- Hydrocephalus ex vacuo also refers to an enlargement of cerebral ventricles and subarachnoid spaces, and is usually due to brain atrophy (as it occurs in dementias), post-traumatic brain injuries, and even in some psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia. As opposed to hydrocephalus, this is a compensatory enlargement of the CSF-spaces in response to brain parenchyma loss; it is not the result of increased CSF pressure.

Mechanism

Spontaneous intracerebral and intraventricular hemorrhage with hydrocephalus shown on CT scan

3D cast of lateral ventricles in hydrocephalus

Hydrocephalus is usually due to blockage of CSF outflow in the

ventricles or in the subarachnoid space over the brain. In a person

without hydrocephalus, CSF continuously circulates through the brain,

its ventricles and the spinal cord

and is continuously drained away into the circulatory system.

Alternatively, the condition may result from an overproduction of the

CSF, from a congenital malformation blocking normal drainage of the

fluid, or from complications of head injuries or infections.

Compression of the brain by the accumulating fluid eventually may cause neurological symptoms such as convulsions, intellectual disability, and epileptic seizures.

These signs occur sooner in adults, whose skulls are no longer able to

expand to accommodate the increasing fluid volume within. Fetuses,

infants, and young children with hydrocephalus typically have an

abnormally large head, excluding the face, because the pressure of the

fluid causes the individual skull bones—which have yet to fuse—to bulge

outward at their juncture points. Another medical sign,

in infants, is a characteristic fixed downward gaze with whites of the

eyes showing above the iris, as though the infant were trying to examine

its own lower eyelids.

The elevated ICP may cause compression of the brain, leading to

brain damage and other complications. Conditions among affected

individuals vary widely.

If the foramina of the fourth ventricle or the cerebral aqueduct

are blocked, CSF can accumulate within the ventricles. This condition is

called internal hydrocephalus and it results in increased CSF pressure.

The production of CSF continues, even when the passages that normally

allow it to exit the brain are blocked. Consequently, fluid builds

inside the brain, causing pressure that dilates the ventricles and

compresses the nervous tissue. Compression of the nervous tissue usually results in irreversible brain damage. If the skull bones are not completely ossified

when the hydrocephalus occurs, the pressure may also severely enlarge

the head. The cerebral aqueduct may be blocked at the time of birth or may become blocked later in life because of a tumor growing in the brainstem.

Treatment

Procedures

Baby recovering from shunt surgery

Hydrocephalus treatment is surgical, creating a way for the excess fluid to drain away. In the short term, an external ventricular drain

(EVD), also known as an extraventricular drain or ventriculostomy,

provides relief. In the long term, some people will need any of various

types of cerebral shunt. It involves the placement of a ventricular catheter (a tube made of silastic)

into the cerebral ventricles to bypass the flow

obstruction/malfunctioning arachnoidal granulations and drain the excess

fluid into other body cavities, from where it can be resorbed. Most

shunts drain the fluid into the peritoneal cavity (ventriculoperitoneal shunt), but alternative sites include the right atrium (ventriculoatrial shunt), pleural cavity (ventriculopleural shunt), and gallbladder. A shunt system can also be placed in the lumbar space of the spine and have the CSF redirected to the peritoneal cavity (lumbar-peritoneal shunt). An alternative treatment for obstructive hydrocephalus in selected people is the endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV), whereby a surgically created opening in the floor of the third ventricle allows the CSF to flow directly to the basal cisterns,

thereby shortcutting any obstruction, as in aqueductal stenosis. This

may or may not be appropriate based on individual anatomy. For infants,

ETV is sometimes combined with choroid plexus cauterization, which

reduces the amount of cerebrospinal fluid produced by the brain. The

technique, known as ETV/CPC, was pioneered in Uganda by neurosurgeon Benjamin Warf and is now in use in several U.S. hospitals.

Hydrocephalus can be successfully treated by placing a drainage tube

(shunt) between the brain ventricles and abdominal cavity. Some risk

exists of infection being introduced into the brain through these shunts, however, and the shunts must be replaced as the person grows.

External hydrocephalus

External

hydrocephalus is a condition generally seen in infants which involves

enlarged fluid spaces or subarachnoid spaces around the outside of the

brain. This is generally a benign condition that resolves spontaneously by two years of age

and therefore usually does not require insertion of a shunt. Imaging

studies and a good medical history can help to differentiate external

hydrocephalus from subdural hemorrhages or symptomatic chronic extra-axial fluid collections which are accompanied by vomiting, headaches, and seizures.

Shunt complications

Examples

of possible complications include shunt malfunction, shunt failure, and

shunt infection, along with infection of the shunt tract following

surgery (the most common reason for shunt failure is infection of the

shunt tract). Although a shunt generally works well, it may stop working

if it disconnects, becomes blocked (clogged) or infected, or it is

outgrown. If this happens, the CSF begins to accumulate again and a

number of physical symptoms develop (headaches, nausea, vomiting, photophobia/light sensitivity), some extremely serious, such as seizures.

The shunt failure rate is also relatively high (of the 40,000 surgeries

performed annually to treat hydrocephalus, only 30% are a person's

first surgery) and people not uncommonly have multiple shunt revisions

within their lifetimes.

Another complication can occur when CSF drains more rapidly than it is produced by the choroid plexus, causing symptoms of listlessness, severe headaches, irritability, light sensitivity, auditory hyperesthesia (sound sensitivity), nausea, vomiting, dizziness, vertigo, migraines, seizures, a change in personality, weakness in the arms or legs, strabismus, and double vision to appear when the person is vertical. If the person lies down, the symptoms usually vanish quickly. A CT scan

may or may not show any change in ventricle size, particularly if the

person has a history of slit-like ventricles. Difficulty in diagnosing

over-drainage can make treatment of this complication particularly

frustrating for people and their families. Resistance to traditional analgesic pharmacological therapy may also be a sign of shunt overdrainage or failure.

The diagnosis of CSF buildup is complex and requires specialist

expertise. Diagnosis of the particular complication usually depends on

when the symptoms appear, that is, whether symptoms occur when the

person is upright or in a prone position, with the head at roughly the

same level as the feet.

Standardized protocols for inserting cerebral shunts have been shown to reduce shunt infections.

History

Skull of a hydrocephalic child (1800s)

References to hydrocephalic skulls can be found in ancient Egyptian medical literature from 2,500 BC to 500 AD.

Hydrocephalus was described more clearly by the ancient Greek physician

Hippocrates in the fourth century BC, while a more accurate description

was later given by the Roman physician Galen in the second century AD.

The first clinical description of an operative procedure for hydrocephalus appears in the Al-Tasrif (1,000 AD) by the Arab surgeon Abulcasis, who clearly described the evacuation of superficial intracranial fluid in hydrocephalic children. He described it in his chapter on neurosurgical disease, describing infantile hydrocephalus as being caused by mechanical compression. He wrote:

The skull of a newborn baby is often full of liquid, either because the matron has compressed it excessively or for other, unknown reasons. The volume of the skull then increases daily, so that the bones of the skull fail to close. In this case, we must open the middle of the skull in three places, make the liquid flow out, then close the wound and tighten the skull with a bandage.

Historical specimen of an infant with severe hydrocephalus, probably untreated

In 1881, a few years after the landmark study of Retzius and Key, Carl Wernicke pioneered sterile ventricular puncture and external drainage of CSF for the treatment of hydrocephalus.

It remained an intractable condition until the 20th century, when

cerebral shunt and other neurosurgical treatment modalities were

developed.

It is a lesser-known medical condition; relatively little

research is conducted to improve treatment, and still no cure has been

found. In developing countries, the condition often goes untreated at

birth. Before birth, the condition is difficult to diagnose, and access

to medical treatment is limited. However, when head swelling is

prominent, children are taken at great expense for treatment. By then,

brain tissue is undeveloped and neurosurgery is rare and difficult.

Children more commonly live with undeveloped brain tissue and

consequential intellectual disabilities and restrictions.

Society and culture

Name

The word "hydrocephalus" is from the Greek ὕδωρ, hydōr meaning "water" and κεφαλή, kephalē meaning "head". Other names for hydrocephalus include "water on the brain", a historical name, and "water baby syndrome".

Awareness campaign

Hydrocephalus awareness ribbon

September was designated National Hydrocephalus Awareness Month in July 2009 by the U.S. Congress in H.Res. 373.

The resolution campaign is due in part to the advocacy work of the

Pediatric Hydrocephalus Foundation. Prior to July 2009, no awareness

month for this condition had been designated. Many of the hydrocephalus

organizations within the U.S. use various ribbon designs as a part of their awareness and fundraising activities.

Exceptional case

One

exceptional case of hydrocephalus was a man whose brain shrank to a

thin sheet of tissue, due to a buildup of cerebrospinal fluid in his

skull. As a child, the man had a shunt, but it was removed when he was

14. In July 2007, at age 44, he went to a hospital due to mild weakness

in his left leg. When doctors learned of the man's medical history, they

performed a CT and MRI scan, and were astonished to see "massive

enlargement" of the lateral ventricles in the skull. Dr. Lionel Feuillet

of Hôpital de la Timone in Marseille said, "The images were most unusual... the brain was virtually absent."

Intelligence tests showed the person had an IQ of 75, considered

"borderline intellectual functioning", just above what would be

officially considered mentally challenged.

The person was a married father of two children, and worked as a

civil servant, leading an at least superficially normal life, despite

having enlarged ventricles with a decreased volume of brain tissue.

"What I find amazing to this day is how the brain can deal with

something which you think should not be compatible with life", commented

Dr. Max Muenke, a pediatric brain-defect specialist at the National Human Genome Research Institute.

"If something happens very slowly over quite some time, maybe over

decades, the different parts of the brain take up functions that would

normally be done by the part that is pushed to the side."

Notable cases

- Author Sherman Alexie, born with the condition, wrote about it in his semi-autobiographical junior fiction novel The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian.

- Prince William, Duke of Gloucester (1689–1700) probably contracted meningitis at birth, which resulted in this condition.

- Emperor Ferdinand I of Austria (1793–1875) became emperor in 1835 despite various health issues including hydrocephalus and epilepsy.