| Autism therapies | |

|---|---|

A

three-year-old with autism points to fish in an aquarium, as part of an

experiment on the effect of intensive shared-attention training on

language development.

|

Autism therapies are interventions that attempt to lessen the deficits and problem behaviours associated with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in order to increase the quality of life and functional independence of individuals with autism. Treatment is typically catered to the person's needs. Treatments fall into two major categories: educational interventions and medical management. Training and support are also given to families of those with ASD.

Studies of interventions have some methodological problems that prevent definitive conclusions about efficacy. Although many psychosocial interventions have some positive evidence, suggesting that some form of treatment is preferable to no treatment, the systematic reviews have reported that the quality of these studies has generally been poor, their clinical results are mostly tentative, and there is little evidence for the relative effectiveness of treatment options. Intensive, sustained special education programs and behavior therapy early in life can help children with ASD acquire self-care, social, and job skills, and often can improve functioning, and decrease symptom severity and maladaptive behaviors; claims that intervention by around age three years is crucial are not substantiated. Although, new research shows that Children who receive intervention can lose their diagnosis and be indistinguishable from their typically developing peers. The earlier the intervention the more likely this to occur. Available approaches include applied behavior analysis (ABA), developmental models, structured teaching, speech and language therapy, social skills therapy, and occupational therapy. Educational interventions have some effectiveness in children: intensive ABA treatment has demonstrated effectiveness in enhancing global functioning in preschool children, and is well established for improving intellectual performance of young children. Neuropsychological reports are often poorly communicated to educators, resulting in a gap between what a report recommends and what education is provided. The limited research on the effectiveness of adult residential programs shows mixed results.

Many medications are used to treat problems associated with ASD. More than half of U.S. children diagnosed with ASD are prescribed psychoactive drugs or anticonvulsants, with the most common drug classes being antidepressants, stimulants, and antipsychotics. Aside from antipsychotics, there is scant reliable research about the effectiveness or safety of drug treatments for adolescents and adults with ASD. A person with ASD may respond atypically to medications, the medications can have adverse effects, and no known medication relieves autism's core symptoms of social and communication impairments.

Some newer treatments are geared towards children with ASD and focus on community-based education and living, and early intervention. The treatments that may have the most benefit focus on early behavioral development and have shown significant improvements in communication and language. These treatments include parental involvement as well as special educational methods. Further research will examine the long term outcome of these treatments and the details surrounding the process and execution of them.

Many alternative therapies and interventions are available, ranging from elimination diets to chelation therapy. Few are supported by scientific studies. Treatment approaches lack empirical support in quality-of-life contexts, and many programs focus on success measures that lack predictive validity and real-world relevance. Scientific evidence appears to matter less to service providers than program marketing, training availability, and parent requests. Even if they do not help, conservative treatments such as changes in diet are expected to be harmless aside from their bother and cost. Dubious invasive treatments are a much more serious matter: for example, in 2005, botched chelation therapy killed a five-year-old boy with autism.

Treatment is expensive; indirect costs are more so. For someone born in 2000, a U.S. study estimated an average discounted lifetime cost of $4.39 million (2020 dollars, inflation-adjusted from 2003 estimate), with about 10% medical care, 30% extra education and other care, and 60% lost economic productivity. A UK study estimated discounted lifetime costs at £1.8 million and £1.16 million for an autistic person with and without intellectual disability, respectively (2020 pounds, inflation-adjusted from 2005/06 estimate). Legal rights to treatment are complex, vary with location and age, and require advocacy by caregivers. Publicly supported programs are often inadequate or inappropriate for a given child, and unreimbursed out-of-pocket medical or therapy expenses are associated with likelihood of family financial problems; one 2008 U.S. study found a 14% average loss of annual income in families of children with ASD, and a related study found that ASD is associated with higher probability that child care problems will greatly affect parental employment. After childhood, key treatment issues include residential care, job training and placement, sexuality, social skills, and estate planning.

Educational interventions

Educational interventions attempt to help children not only to learn

academic subjects and gain traditional readiness skills, but also to

improve functional communication and spontaneity, enhance social skills

such as joint attention,

gain cognitive skills such as symbolic play, reduce disruptive

behavior, and generalize learned skills by applying them to new

situations. Several model programs have been developed, which in

practice often overlap and share many features, including:

- early intervention that does not wait for a definitive diagnosis;

- intense intervention, at least 25 hours per week, 12 months per year;

- low student/teacher ratio;

- family involvement, including training of parents;

- interaction with neurotypical peers;

- social stories, ABA and other visually based training;

- structure that includes predictable routine and clear physical boundaries to lessen distraction; and

- ongoing measurement of a systematically planned intervention, resulting in adjustments as needed.

Several educational intervention methods are available, as discussed

below. They can take place at home, at school, or at a center devoted to

autism treatment; they can be done by parents, teachers, speech and language therapists, and occupational therapists. A 2007 study found that augmenting a center-based program with weekly home visits by a special education teacher improved cognitive development and behavior.

Studies of interventions have methodological problems that prevent definitive conclusions about efficacy. Although many psychosocial

interventions have some positive evidence, suggesting that some form of

treatment is preferable to no treatment, the methodological quality of systematic reviews

of these studies has generally been poor, their clinical results are

mostly tentative, and there is little evidence for the relative

effectiveness of treatment options.

Concerns about outcome measures, such as their inconsistent use, most

greatly affect how the results of scientific studies are interpreted.

A 2009 Minnesota study found that parents follow behavioral treatment

recommendations significantly less often than they follow medical

recommendations, and that they adhere more often to reinforcement than

to punishment recommendations.

Intensive, sustained special education programs and behavior therapy

early in life can help children acquire self-care, social, and job

skills, and often improve functioning and decrease symptom severity and maladaptive behaviors; claims that intervention by around age three years is crucial are not substantiated.

Applied behavior analysis

Applied behavior analysis (ABA) is the applied research field of the science of behavior analysis, and it underpins a wide range of techniques used to treat autism and many other behaviors and diagnoses, including those who are patients in rehab or in whom a behavior change is desired

. ABA-based interventions focus on teaching tasks one-on-one using the behaviorist principles of stimulus, response and reward, and on reliable measurement and objective evaluation of observed behavior. Applied Behavior Analysis is the only empirically proven method of treatment. There is wide variation in the professional practice of behavior analysis and among the assessments and interventions used in school-based ABA programs.

Conversely, various major figures within the autistic community

have written biographies detailing the harm caused by the provision of

ABA, including restraint, sometimes used with mild self stimulatory

behaviors such as hand flapping, and verbal abuse. The Autistic Self Advocacy Network campaigns against the use of ABA in autism

- punishment procedures are very rarely used within the field today.

These procedures were once used in the 70s and 80s however now there are

ethical guidelines in place to prohibit the use.

Discrete trial training

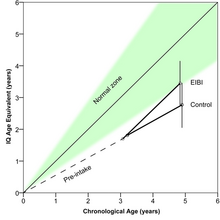

Developmental

trajectories (as measured with IQ-tests) of children with autism

receiving either early and intensive behavioral intervention (n=195) or

control treatment (n = 135)

Many intensive behavioral interventions rely heavily on discrete

trial teaching (DTT) methods, which use stimulus-response-reward

techniques to teach foundational skills such as attention, compliance,

and imitation. However, children have problems using DTT-taught skills in natural environments.

These students are also taught with naturalistic teaching procedures to

help generalize these skills. In functional assessment, a common

technique, a teacher formulates a clear description of a problem

behavior, identifies antecedents, consequences, and other environmental

factors that influence and maintain the behavior, develops hypotheses

about what occasions and maintains the behavior, and collects

observations to support the hypotheses. A few more-comprehensive ABA programs use multiple assessment and intervention methods individually and dynamically.

ABA-based techniques have demonstrated effectiveness in several

controlled studies: children have been shown to make sustained gains in

academic performance, adaptive behavior, and language, with outcomes significantly better than control groups.

A 2009 review of educational interventions for children, whose mean age

was six years or less at intake, found that the higher-quality studies

all assessed ABA, that ABA is well-established and no other educational

treatment is considered probably efficacious, and that intensive ABA

treatment, carried out by trained therapists, is demonstrated effective

in enhancing global functioning in pre-school children. These gains maybe complicated by initial IQ.

A 2008 evidence-based review of comprehensive treatment approaches

found that ABA is well established for improving intellectual

performance of young children with ASD.

A 2009 comprehensive synthesis of early intensive behavioral

intervention (EIBI), a form of ABA treatment, found that EIBI produces

strong effects, suggesting that it can be effective for some children

with autism; it also found that the large effects might be an artifact

of comparison groups with treatments that have yet to be empirically

validated, and that no comparisons between EIBI and other widely

recognized treatment programs have been published.

A 2009 systematic review came to the same principal conclusion that

EIBI is effective for some but not all children, with wide variability

in response to treatment; it also suggested that any gains are likely to

be greatest in the first year of intervention. A 2009 meta-analysis concluded that EIBI has a large effect on full-scale intelligence and a moderate effect on adaptive behavior.

However, a 2009 systematic review and meta-analysis found that applied

behavior intervention (ABI), another name for EIBI, did not

significantly improve outcomes compared with standard care of preschool

children with ASD in the areas of cognitive outcome, expressive

language, receptive language, and adaptive behavior.

Applied behavior analysis is cost effective for administrators.

Recently behavior analysts have built comprehensive models of child development to generate models for prevention as well as treatment for autism.

Pivotal response training

Pivotal response treatment (PRT) is a naturalistic intervention

derived from ABA principles. Instead of individual behaviors, it targets

pivotal areas of a child's development, such as motivation,

responsivity to multiple cues, self-management, and social initiations;

it aims for widespread improvements in areas that are not specifically

targeted. The child determines activities and objects that will be used

in a PRT exchange. Intended attempts at the target behavior are rewarded

with a natural reinforcer: for example, if a child attempts a request

for a stuffed animal, the child receives the animal, not a piece of

candy or other unrelated reinforcer.

Aversive therapy

The Judge Rotenberg Educational Center uses aversion therapy, notably contingent shock (electric shock

delivered to the skin for a few seconds), to control the behavior of

its patients, many of whom are autistic. The practice is controversial and has not been popular or used elsewhere since the 1990s.

Communication interventions

The inability to communicate, verbally or non-verbally, is a core

deficit in autism. Children with autism are often engaged in repetitive

activity or other behaviors because they cannot convey their intent any

other way. They do not know how to communicate their ideas to caregivers

or others. Helping a child with autism learn to communicate their needs

and ideas is absolutely core to any intervention. Communication can

either be verbal or non-verbal. Children with autism require intensive

intervention to learn how to communicate their intent.

Communication interventions fall into two major categories.

First, many autistic children do not speak, or have little speech, or

have difficulties in effective use of language. Social skills have been shown to be effective in treating children with autism.

Interventions that attempt to improve communication are commonly

conducted by speech and language therapists, and work on joint

attention, communicative intent, and alternative or augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) methods such as visual methods, for example visual schedules. AAC methods do not appear to impede speech and may result in modest gains. A 2006 study reported benefits both for joint attention intervention and for symbolic play intervention,

and a 2007 study found that joint attention intervention is more likely

than symbolic play intervention to cause children to engage later in

shared interactions.

Second, social skills treatment attempts to increase social and

communicative skills of autistic individuals, addressing a core deficit

of autism. A wide range of intervention approaches is available,

including modeling and reinforcement, adult and peer mediation

strategies, peer tutoring, social games and stories, self-management, pivotal response therapy, video modeling, direct instruction, visual cuing, Circle of Friends and social-skills groups.

A 2007 meta-analysis of 55 studies of school-based social skills

intervention found that they were minimally effective for children and

adolescents with ASD, and a 2007 review found that social skills training has minimal empirical support for children with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism.

SCERTS

The SCERTS model

is an educational model for working with children with autism spectrum

disorder (ASD). It was designed to help families, educators and

therapists work cooperatively together to maximize progress in

supporting the child.

The acronym refers to the focus on:

- SC – social communication – the development of functional communication and emotional expression.

- ER – emotional regulation – the development of well-regulated emotions and ability to cope with stress.

- TS – transactional support – the implementation of supports to help families, educators and therapists respond to children's needs, adapt the environment and provide tools to enhance learning.

The evidence base for the efficacy of the SCERTS Model Practice in

the SCERTS model is based on evidence from multiple sources. Efficacy of

implementation of practices in the SCERTS Model is supported by

empirical evidence from contemporary treatment research in ASD and

related disabilities. Currently, federally funded, large sample research

has been published and longitudinal studies continue that specifically

addresses the effectiveness of SCERTS as a comprehensive treatment

framework. The emphasis of current research is to demonstrate the

effectiveness of SCERTS for infants, toddlers and school age students in

home, school and community settings. This body of research is

summarized below. Second, it is rooted in research on child development

as well as research addressing the core challenges of ASD. Third, it

incorporates the documentation of meaningful change through the

collection of clinical and educational data, and programmatic decisions

are made based on objective measurement of change. Finally, given that

it is not an exclusive model, evidence-based practices (i.e., focused

intervention strategies) from other approaches are easily infused in a

program plan for an individual.

Empirical Research on the Efficacy of The SCERTS Model

In recent years a number of studies have been published that

highlight the efficacy of the SCERTS model. Two randomized controlled

trials have been published demonstrating the efficacy of the SCERTS

Model in the home and classroom settings. The first randomized trial

adapted the SCERTS framework for delivery within early intervention

settings (Wetherby et al., 2014). Specifically, this study examined the

effectiveness of the model when implemented by parents for toddlers with

autism within natural settings. Eighty-two autistic children aged 19

months (SD = 1.93 mos) participated in a 9-month longitudinal study with

their primary caregiver. Children were randomized into two groups – an

individual coaching format and a group coaching format, both focused on

teaching parents how to support active engagement within natural

contexts using the SCERTS framework. Individual coaching consisted of

in-home support from an interventionist 2-3 times weekly using a

collaborative coaching model to build parent capacity and independence

in implementation of supports within natural routines geared at

facilitating SC and ER development. Parents in this condition were

encouraged to deliver intervention by embedding evidence-based

strategies for their child’s SC and ER targets in everyday activities

for at least 25 hours. This is consistent with the SCERTS Model

recommendations. Results found individual coaching was more efficacious

than the group-based format. Outcomes for social communication,

receptive language, and adaptive behavior reached statistical

significance (Wetherby et al., 2014).

The efficacy of the SCERTS Model in classrooms was the focus of

another large longitudinal randomized control trial. Morgan et al.

(2018) conducted a cluster randomized controlled trial for 197 diverse

students with ASD in 129 classrooms across 66 schools in the US. Mean

age of the students was 6.76 years (SD = 1.05years). Classrooms were

randomly assigned to the Classroom SCERTS Intervention (CSI) or Autism

Training Modules (ATM) condition. Special education and general

education teachers assigned to the CSI condition in this study were

trained on the model and provided coaching throughout the school year.

ATM teachers engaged in usual school-based educational practices and had

access to online training resources related to autism treatment

practices. Notably, in this study active engagement was used as an

outcome measure and was measured by the Classroom Measure of Active

Engagement (CMAE; Morgan, Wetherby & Holland, 2010). Additional

outcome measures examining adaptive behavior, social skills, and ratings

of executive functioning were also used.

Results of Morgan et al. (2018) revealed that students in the CSI

condition showed statistically significant better outcomes on observed

measures of adaptive communication, social skills and executive

functioning than students within the ATM condition. These data

demonstrate the positive impact of SCERTS within a natural environment,

that is, the classroom setting, for a heterogeneous sample of students

with ASD (Morgan et al., 2018). This study was chosen by the

Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee in the US for their 2018

Summary of Advances in Autism Spectrum Disorder Research Report as a key

study addressing the question “Which treatments and interventions will

help?” In their review, the Committee highlighted that 70 percent of

teachers trained in CSI implemented with fidelity indicating scalability

of the model and also reflecting feasibility with teacher commitment to

the model. They also acknowledged that this is one of the largest

studies to measure the effect of school-based active engagement

intervention in children with ASD and that the results appear

generalizable to a diverse population (Interagency Autism Coordinating

Committee (IACC), 2019).

The prioritization of active engagement as a measure of

effectiveness for educational programs for students with ASD aligns with

work by Sparapani and colleagues (2015) that identifies the challenges

students diagnosed with autism face in terms of maintaining active

engagement and the resulting impact on learning and educational

outcomes. In fact, results suggest typically students with autism

actively engage less than half of the time in the classroom (Sparapani,

Morgan, Reinhardt, Schatschneider, & Wetherby, 2015). Consideration

of this finding in the context of additional research suggests that

increasing active engagement is critical to positive educational

outcomes in ASD and reveals a clear need for approaches such as SCERTS

that focus on active engagement (National Research Council, 2001).

The SCERTS Model has also been the object of international study.

A pilot study was implemented in Hong Kong examining the effectiveness

of the SCERTS® Model for children with ASD (Yu & Zhu, 2018). This

study examined the implementation of SCERTS® for 2 different durations

(5 months versus 10 months) for children with an average age of 53

months in preschool settings. Special education teachers, occupational

therapists, speech pathologists, and physiotherapists were recruited

from 10 special child care centers in Hong Kong. Participating

professionals received initial training and then were provided coaching

throughout the school year. Each participating special education teacher

taught 5-7 children. Results showed that participating children

improved significantly in their social communication and emotional

behavior after intervention.

The SCERTS Model has also been the subject of a multiple case

study design (O’Neill et al., 2010). Implementation of SCERTS in this

study followed a multi-disciplinary team training for the teams of four

pupils. All four pupils made progress in Joint Attention, Symbol Use,

Mutual Regulation, and Self-Regulation as well as in other measures of

receptive communication, expressive communication, play, and coping

skills. Qualitative methods were used to gain insights from the staff

related to their experiences in implementing SCERTS. Central findings

from the focus groups with the multidisciplinary team members revealed

increased understanding of emotional regulation as a developmental

construct, as well as increased clarity of team member roles in

supporting children when dysregulated.

Researchers in the United Kingdom (Molteni, Guldberg, &

Logan, 2013) also examined the feasibility of implementing SCERTS as an

ecologically valid model in an independent residential school. This

study aimed to understand how teams work together while learning to

implement the SCERTS Model. At the conclusion of the study, 89% of the

team members said they felt comfortable using SCERTS and 78% said the

framework improved teamwork in collaborating with colleagues.

Specifically, teams highlighted that the quality and accuracy of

assessment improved collaboration and understanding of students and

their environment.

Summary

The SCERTS Model meets criteria for evidence-based practice and

offers a framework to directly address the core challenges of ASD,

focusing on building an individual’s capacity to initiate communication

with a conventional symbolic system and to be actively engaged in

emotionally satisfying relationships based on effective reciprocal

communication. Emotional regulation goals focus on capacities to

regulate attention, arousal and emotional state to cope with everyday

stresses in life, and therefore, to be most available for learning and

engaging. Transactional supports are identified, developed and

implemented to support individuals of all ages in social engagement and

learning, to promote generalization of acquired abilities, and to

support their caregivers service providers. The model provides a

roadmap for individualized education and treatment based on a person’s

strengths and needs guided by research on child and human development.

The SCERTS Model was designed to motivate professionals and families to

focus their efforts on enhancing quality of life by addressing the core

challenges faced by autistic children, adults and their caregivers, and

therefore, to move the field to a new generation of more integrated,

comprehensive programs.

Disley, B. Weston, B., Kolandai-Matchett, K., Vermillion Peirce,

P. (2011). Evaluation of the use of the Social Communication, Emotional

Regulation and Transactional Support (SCERTS) Framework in New Zealand.

Prepared for: Warwick Phillips Professional Practice Unit, Special

Education Ministry of Education. Cognition Education Limited 2011. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1467-8578.12030/abstract

Fukuzawa, Y. (2017). Enhancing the active engagement of students with

special needs through emotional regulation : The SCERTS Model in special

needs school. Study Report: Shizuoka University.

Harrison, P. (2015, May). Classroom-Based intervention improves core

autism deficits; summary of classroom SCERTS intervention (CSI) data

presented at IMFAR in May 2015; Medscape. Accessible via: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/844530

Molteni, P., Guldberg, K., and Logan, N. (2013). Autism and

multidisciplinary teamwork through the SCERTS Model, British Journal of

Special Education. DOI: 10.1111/1467-8578.12030. Accessible via: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1467-8578.12030/abstract

Morgan L, Hooker JL, Sparapani N, et al., (2018) Cluster randomized

trial of the classroom SCERTS intervention for elementary students with

autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology.

J86(7):631-644.

O’Neill, J., Bergstrand, L., Bowman, K., Elliott, K., Mavin, L.,

Stephenson, S., Wayman, C. (2010). The SCERTS model: Implementation and

evaluation in a primary special school. Good Autism Practice (GAP),

11,1, 2010. Accessible on the Autism Education Trust website at: http://www.aettraininghubs.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/31.1-ONeill-Evaluating-practice.pdf

Sparapani, N, Morgan, L., Reinhardt, V., Schatschneider, C., &

Wetherby, A.M. (2015). Evaluation of Classroom Active Engagement in

Elementary Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and

Developmental Disorders,

Wetherby, A,M., Guthrie, W., Woods, J., Schatschneider, C., Holland, R.,

Morgan, L. & Lord, C. (2014). Parent-Implemented Social

Intervention for Toddlers With Autism: An RCT. Pediatrics

Yu, L., and Zhu, X. (2018). Effectiveness of a SCERTS Model-based

intervention for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in Hong

Kong: A pilot study, Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders,

1-14.

Computer-assisted therapy for reasoning about communicative actions

Many

remediation strategies have not taken into account that people with

autism suffer from difficulties in learning social rules from examples.

Computer-assisted autism therapy has been proposed to teach not simply

via examples but to teach the rule along with it.

A reasoning rehabilitation strategy, based on playing with a computer

based mental simulator that is capable of modeling mental and emotional

states of the real world, has been subject to short-term and long-term

evaluations. The simulator performs the reasoning in the framework of belief-desire-intention model.

Learning starts from the basic concepts of knowledge and intention and

proceeds to more complex communicative actions such as explaining,

agreeing, and pretending.

Relationship based, developmental models

Relationship

based models give importance to the relationships that help children

reach and master early developmental milestones. These are often missed

or not mastered in children with ASD. Examples of these early milestones

are engagement and interest in the world, intimacy with a caregiver,

intentionality of action.

Relationship Development Intervention

Relationship development intervention

is a family-based treatment program for children with autism spectrum

disorder (ASD). This program is based on the belief that the development

of dynamic intelligence (the ability to think flexibly, take different

perspectives, cope with change and process information simultaneously)

is key to improving the quality of life of children with autism.

Floortime/DIR

The Floortime/DIR (Developmental, Individual Differences based,

Relationship based ) approach is a developmental intervention to autism

developed by Stanley Greenspan and Serena Weider. This approach is based on the idea that the core deficits in autism are individual differences in the sensory system, motor planning

problems, difficulties in communication and relation to others, and the

inability to connect ones desire to intentional action and

communication. When addressed through a combination of sensory support

and DIR/Floortime techniques, the facilitator is playfully obstructive

to redirect the child to play and relate to their therapist. The primary

goal of Floortime is to improve the child's cognitive, language, and

social abilities.

However, these claims should be regarded with some scepticism, owing to

a lack of independent scientific research into the efficacy of the

floortime approach.

The DIR model is based on the model of a developmental 'tree',

the central notion being that Autistic children have yet to master

certain early developmental milestones, or 'branches' of the tree, which

are as follows:

- Stage One: Regulation and Interest in the World: Being calm and feeling well enough to attend to a caregiver and surroundings. Have shared attention.

- Stage Two: Engagement and Relating: Interest in another person and in the world, developing a special bond with preferred caregivers. Distinguishing inanimate objects from people.

- Stage Three: Two way intentional communication: Simple back and forth interactions between child and caregiver. Smiles, tickles, anticipatory play.

- Stage Four: Social Problem solving: Using gestures, interaction, babble to indicate needs, wants, pleasure, upset. Get a caregiver to help with a problem. Using pre-language skills to show intention.

- Stage Five: Symbolic Play: Using words, pictures, symbols to communicate an intention, idea. Communicate ideas and thoughts, not just wants and needs.

- Stage Six: Bridging Ideas: This stage is the foundation of logic, reasoning, emotional thinking and a sense of reality.

Exponents of the floortime approach argue that children with ASD

struggle with or have missed some of these vital developmental stages.

An introduction to DIR/Floortime can be found in the book - Engaging

Autism: Using the Floortime Approach to Help Children Relate,

Communicate, and Think, by Stanley Greenspan, M.D. and Serena Wieder, PhD.

The PLAY Project

The PLAY Project (an acronym for PLAY and Language for Autistic Youngsters) is a community-based, national autism training and early childhood intervention program established in 2001 by Richard Solomon. Based on the DIR (Developmental, Individualized, Relationship-based) theory of Stanley Greenspan MD,

the program is designed to train parents and professionals to implement

intensive, developmental interventions for young children (18 months to

6 years) with autism. The program is operating in nearly 100 agencies

worldwide including 25 states and in 5 countries outside of the U.S.

(Australia, Canada, England, Ireland, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and

China). The PLAY Project has been operating since 2001 from its headquarters in Ann Arbor, MI.

Some preliminary research on the program was published by the peer-reviewed British journal, Autism (May, 2007).

Son-Rise

Son-Rise is a home-based program that emphasizes on implementing a

color- and sensory-free playroom. Before implementing the home-based

program, an institute trains the parents how to accept their child

without judgment through a series of dialogue sessions. Like Floortime,

parents join their child's ritualistic behavior for

relationship-building. To gain the child's "willing engagement", the

facilitator continues to join them only this time through parallel play.

Proponents claim that children will become non-autistic after parents

accept them for who they are and engage them in play. The program was

started by the parents of Raun Kaufman, who is claimed to have gone from being autistic to normal via the treatment in the early 1970s.

No independent study has tested the efficacy of the program, but a 2003

study found that involvement with the program led to more drawbacks

than benefits for the involved families over time,

and a 2006 study found that the program is not always implemented as it

is typically described in the literature, which suggests it will be

difficult to evaluate its efficacy.

TEACCH

Treatment and Education of Autistic and Related Communication

Handicapped Children (TEACCH), which has come to be called "structured

teaching", emphasises structure by using organized physical

environments, predictably sequenced activities, visual schedules and

visually structured activities, and structured work/activity systems

where each child can practice various tasks.

Parents are taught to implement the treatment at home. A 1998

controlled trial found that children treated with a TEACCH-based home

program improved significantly more than a control group.

A 2013 meta-analysis compiling all the clinical trials of TEACCH

indicated that it has small or no effects on perceptual, motor, verbal,

cognitive, and motor functioning, communication skills, and activities

of daily living. There were positive effects in social and maladaptive

behavior, but these required further replication due to the

methodological limitations of the pool of studies analysed.

Sensory integration

Unusual responses to sensory stimuli

are more common and prominent in children with autism, although there

is not good evidence that sensory symptoms differentiate autism from

other developmental disorders. Several therapies have been developed to treat Sensory processing disorder. Some of these treatments (for example, sensorimotor

handling) have a questionable rationale and have no empirical evidence.

Other treatments have been studied, with small positive outcomes, but

few conclusions can be drawn due to methodological problems with the

studies. These treatments include prism lenses, physical exercise, auditory integration training,

and sensory stimulation or inhibition techniques such as "deep

pressure"—firm touch pressure applied either manually or via an

apparatus such as a hug machine or a pressure garment.

Weighted vests, a popular deep-pressure therapy, have only a limited

amount of scientific research available, which on balance indicates that

the therapy is ineffective.

Although replicable treatments have been described and valid outcome

measures are known, gaps exist in knowledge related to Sensory

processing disorder and therapy.

In a 2011 Cochrane review, no evidence was found to support the use of

auditory integration training as an ASD treatment method. Because empirical support is limited, systematic evaluation is needed if these interventions are used.

The term multisensory integration in simple terms means the ability to use all of ones senses to accomplish a task. Occupational therapists

sometimes prescribe sensory treatments for children with Autism however

in general there has been little or no scientific evidence of

effectiveness.

Animal-assisted therapy

Animal-assisted therapy,

where an animal such as a dog or a horse becomes a basic part of a

person's treatment, is a controversial treatment for some symptoms. A

2007 meta-analysis found that animal-assisted therapy is associated with a moderate improvement in autism spectrum symptoms. Reviews of published dolphin-assisted

therapy (DAT) studies have found important methodological flaws and

have concluded that there is no compelling scientific evidence that DAT

is a legitimate therapy or that it affords any more than fleeting

improvements in mood.

Neurofeedback

Neurofeedback

attempts to train individuals to regulate their brainwave patterns by

letting them observe their brain activity more directly. In its most

traditional form, the output of EEG electrodes is fed into a computer

that controls a game-like audiovisual display. Neurofeedback has been

evaluated with positive results for ASD, but studies have lacked random

assignment to controls.

Patterning

Patterning

is a set of exercises that attempts to improve the organization of a

child's neurologic impairments. It has been used for decades to treat

children with several unrelated neurologic disorders, including autism.

The method, taught at The Institutes for the Achievement of Human Potential, is based on oversimplified theories and is not supported by carefully designed research studies.

Packing

In

packing, children are wrapped tightly for up to an hour in wet sheets

that have been refrigerated, with only their heads left free. The

treatment is repeated several times a week, and can continue for years.

It is intended as treatment for autistic children who harm themselves;

most of these children cannot speak. Similar envelopment techniques have

been used for centuries, such as to calm violent patients in Germany in

the 19th century; its modern use in France began in the 1960s, based on

psychoanalytic theories such as the theory of the refrigerator mother.

Packing is currently used in hundreds of French clinics. There is no

scientific evidence for the effectiveness of packing, and some concern

about risk of adverse health effects.

Other methods

There

are many simple methods such as priming, prompt delivery, picture

schedules, peer tutoring, and cooperative learning, that have been

proven to help autistic students to prepare for class and to understand

the material better. Priming is done by allowing the students to see the

assignment or material before they are shown in class. Prompt delivery

consists of giving prompts to the autistic children in order to elicit a

response to the academic material. Picture schedules are used to

outline the progression of a class and are visual cues to allow autistic

children to know when changes in the activity are coming up. This

method has proven to be very useful in helping the students follow the

activities. Peer tutoring and cooperative learning are ways in which an

autistic student and a nonhandicapped student are paired together in the

learning process. This has shown be very effective for “increasing both

academic success and social interaction.” There are more specific strategies that have been shown to improve an autistic’s education, such as LEAP, Treatment and Education of Autistic and Related Communication Handicapped Children,

and Non-Model-Specific Special Education Programs for preschoolers.

LEAP is “an intensive 12-month program that focuses on providing a

highly structured and safe environment that helps students to

participate in and derive benefit from educational programming” and

focuses on children from 5-21 who have a more severe case of autism.

The goal of the program is to develop functional independence through

academic instruction, vocational/translational curriculum,

speech/language services, and other services personalized for each

student.

While LEAP, TEACCH, and Non-Model Specific Special Education Programs

are all different strategies, there has been no evidence that one is

more effective than the other.

Societal aspects

Martha

Nussbaum discusses how education is one of the fertile functions that

is important for the development of a person and their ability to

achieve a multitude of other capabilities within society.

Autism causes many symptoms that interfere with a child’s ability to

receive a proper education such as deficits in imitation, observational

learning, and receptive and expressive communication. Of all

disabilities affecting the population, autism ranks third lowest in

acceptance into a postsecondary education institution.

In a study funded by the National Institute of Health, Shattuck et al.

found that only 35% of autistics are enrolled in a 2 or 4 year college

within the first two years after leaving high school compared to 40% of

children who have a learning disability.

Due to the growing need for a college education to obtain a job, this

statistic shows how autistics are at a disadvantage in gaining many of

the capabilities that Nussbaum discusses and makes education more than

just a type of therapy for those with autism.

According to the study by Shattuck, only 55% of children with autism

participated in any paid employment within the first two years after

high school. Furthermore, those with autism that come from low income

families tend to have lower success in postsecondary schooling. Due to these issues, education has become more than just an issue of therapy for those with autism but also a social issue.

Disadvantages

Oftentimes,

schools simply lack the resources to create an optimal classroom

setting for those in need of special education. In the United States, it

can cost between $6595 to $10,421 extra to educate a child with autism.

In the 2011-2012 school year, the average cost of education for a

public school student was $12,401. In some cases, the extra cost

required to educate a child with autism nearly doubles the average cost

to educate the average public school student.

As the range of those with autism can widely vary, it is very difficult

to create an autism program that is well suited to the entire

population of autistics as well as those with other disabilities. In the

United States, many school districts are requiring schools to meet the

needs of disabled students, regardless of the number of children with

disabilities there are in the school.

This combined with a shortage of licensed special education teachers

has created a deficiency in the special education system. The shortage

has caused some states to give temporary special education licenses to

teachers with the caveat that they receive a license within a few years.

Policies

In

the United States, there have been three major policies addressing

special education in the United States. These policies were the Education for All Handicapped Children Act in 1975, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act in 1997, and the No Child Left Behind

in 2001. The development of these policies showed increased guidelines

for special education and requirements; such as requiring states to fund

special education, equality of opportunities, help with transitions

after secondary schooling, requiring extra qualifications for special

education teachers, and creating a more specific class setting for those

with disabilities. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act,

specifically had a large impact on special education as public schools

were then required to employ high qualified staff. For one to be a

Certified Autism Specialist, one must have a master's degree, two years

of career experience working with the autism population, earn 14

continuing education hours in autism every two years, and register with

the International Institute of Education.

In 1993, Mexico passed an education law that called for the inclusion

of those with disabilities. This law was very important for Mexico

education, however, there have been issues in implementing it due to a

lack of resources.

There have also been multiple international groups that have

issued reports addressing issues in special education. The United

Nations on “International Norms and Standards relating to Disability” in

1998. This report cites multiple conventions, statements, declarations,

and other reports such as: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights,

The Salamanca Statement, the Sundberg Declaration, the Copenhagen

Declaration and Programme of Action, and many others. One main point

that the report emphasizes is the necessity for education to be a human

right. The report also states that the “quality of education should be

equal to that of persons without disabilities.” The other main points

brought up by the report discuss integrated education, special education

classes as supplementary, teacher training, and equality for vocational education.

The United Nations also releases a report by the Special Rapporteur

that has a focus on persons with disabilities. In 2015, a report titled

“Report of the Special Rapporteur to the 52nd Session of the Commission

for Social Development: Note by the Secretary-General on Monitoring of

the implementation of the Standard Rules on the Equalization of

Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities” was released. This report

focused on looking at how the many countries involved, with a focus on

Africa, have handled policy regarding persons with disabilities. In this

discussion, the author also focuses on the importance of education for

persons with disabilities as well as policies that could help improve

the education system such as a move towards a more inclusive approach.

The World Health Organization has also published a report addressing

people with disabilities and within this there is a discussion on

education in their “World Report on Disability” in 201. Other organizations that have issued reports discussing the topic are UNESCO, UNICEF, and the World Bank.

Environmental enrichment

Environmental enrichment is concerned with how the brain is affected by the stimulation of its information processing

provided by its surroundings (including the opportunity to interact

socially). Brains in richer, more-stimulating environments, have

increased numbers of synapses, and the dendrite arbors upon which they reside are more complex. This effect happens particularly during neurodevelopment,

but also to a lesser degree in adulthood. With extra synapses there is

also increased synapse activity and so increased size and number of glial energy-support cells. Capillary vasculation also is greater to provide the neurons and glial cells with extra energy. The neuropil

(neurons, glial cells, capillaries, combined together) expands making

the cortex thicker. There may also exist (at least in rodents) more neurons.

Research on nonhuman animals finds that more-stimulating

environments could aid the treatment and recovery of a diverse variety

of brain-related dysfunctions, including Alzheimer's disease and those connected to aging, whereas a lack of stimulation might impair cognitive development.

Research on humans suggests that lack of stimulation

(deprivation—such as in old-style orphanages) delays and impairs

cognitive development. Research also finds that higher levels of

education (which is both cognitively stimulating in itself, and

associates with people engaging in more challenging cognitive

activities) results in greater resilience (cognitive reserve) to the effects of aging and dementia.

Massage therapy

A review of massage therapy

as a symptomatic treatment of autism found limited evidence of benefit.

There were few high quality studies, and due to the risk of bias found in the studies analyzed, no firm conclusions about the efficacy of massage therapy could be drawn.

Music

Music therapy

uses the elements of music to let people express their feelings and

communicate. A 2014 review found that music therapy may help in social

interactions and communication.

Music therapy can involve various techniques depending on where the subject is sitting on the ASD scale.

Somebody who may be considered as 'low-functioning' would require

vastly different treatment to somebody on the ASD scale who is

'high-functioning'. Examples of these types of therapeutic techniques

include:

- Free improvisation - No boundaries or skills required

- Structured improvisation - Some established parameters within the music

- Performing or recreating music - Reproducing a pre-composed piece of music or song with associated activities

- Composing music - Creating music that caters to the specific needs of that person using instruments or the voice

- Listening - Engaging in specific musical listening base exercises

Improvisational Music Therapy (IMT), is increasing in popularity as a

therapeutic technique being applied to children with ASD. The process

of IMT occurs when the client and therapist make up music, through the

use of various instruments, song and movement. The specific needs of

each child or client need to be taken into consideration. Some children

with ASD find their different environments chaotic and confusing,

therefore, IMT sessions require the presence of a certain routine and be

predictable in nature, within their interactions and surroundings.

Music can provide all of this, it can be very predicable, it is highly

repetitious with its melodies and sounds, but easily varied with

phrasing, rhythm and dynamics giving it a controlled flexibility. The

allowance of parents or caregivers to sessions can put the child at ease

and allow for activities to be incorporated into everyday life.

Sensory enrichment therapy

In

all interventions for autistic children, the main strategy is to aim

towards the improvement on sensitivity in all senses. Autistic children

suffer from a lack of the ability to derive and sort out their senses as

well as the feelings and moods of the people around them. Many children with autism suffer from this Sensory Processing Disorder.

In sensory-based interventions, there have been signs of progress in

children responding with an appropriate response when given a stimulus

after being in sensory-based therapies for a period of time. However, at

this time, there is no concrete evidence that these therapies are

effective for children with Autism.

Autism is a very complex disorder and differs from child to child. This

makes the effectiveness of each type of therapy and even therapy

activity vary.

The purpose of these differentiated interventions are to

intervene at the neurological level of the brain in hopes to develop

appropriate responses to the different sensations from one's body and

also to outside stimuli in one's environment. Scientist have used music

therapies, massage therapies, occupational therapies and more. With the

Autistic Spectrum being so diverse and widespread, each case or scenario

is different.

Parent mediated interventions

Parent mediated interventions offer support and practical advice to parents of autistic children. A 2002 Cochrane Review

found only two relevant studies, with small numbers of participants,

and no clinical recommendations could be made due to these limitations.

A very small number of randomized and controlled studies suggest that

parent training can lead to reduced maternal depression, improved

maternal knowledge of autism and communication style, and improved child

communicative behavior, but due to the design and number of studies

available, definitive evidence of effectiveness is not available.

Early detection of ASD in children can often occur before a child

reaches the age of three years old. Methods that target early behavior

can influence the quality of life for a child with ASD. Parents can

learn methods of interaction and behavior management to best assist

their child's development. A 2013 Cochrance review concluded that there

were some improvements when parent intervention was used.

Medical management

Drugs,

supplements, or diets are often used to alter physiology in an attempt

to relieve common autistic symptoms such as seizures, sleep

disturbances, irritability, and hyperactivity that can interfere with

education or social adaptation or (more rarely) cause autistic

individuals to harm themselves or others.

There is plenty of anecdotal evidence to support medical treatment;

many parents who try one or more therapies report some progress, and

there are a few well-publicized reports of children who are able to

return to mainstream education after treatment, with dramatic

improvements in health and well-being. However, this evidence may be

confounded by improvements seen in autistic children who grow up without

treatment, by the difficulty of verifying reports of improvements, and

by the lack of reporting of treatments' negative outcomes. Only a very few medical treatments are well supported by scientific evidence using controlled experiments.

Prescription medication

Many medications are used to treat problems associated with ASD. More than half of U.S. children diagnosed with ASD are prescribed psychoactive drugs or anticonvulsants, with the most common drug classes being antidepressants, stimulants, and antipsychotics. Only the antipsychotics have clearly demonstrated efficacy.

Research has focused on atypical antipsychotics, especially risperidone,

which has the largest amount of evidence that consistently shows

improvements in irritability, self-injury, aggression, and tantrums

associated with ASD. Risperidone is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating symptomatic irritability in autistic children and adolescents. In short-term trials (up to six months) most adverse events were mild to moderate, with weight gain, drowsiness, and high blood sugar requiring monitoring; long term efficacy and safety have not been fully determined. It is unclear whether risperidone improves autism's core social and communication deficits.

The FDA's decision was based in part on a study of autistic children

with severe and enduring problems of tantrums, aggression, and

self-injury; risperidone is not recommended for autistic children with

mild aggression and explosive behavior without an enduring pattern.

Other drugs are prescribed off-label in the U.S., which means they have not been approved for treating ASD. Large placebo-controlled studies of olanzapine and aripiprazole were underway in early 2008.

Aripiprazole may be effective for treating autism in the short term,

but is also associated with side effects, such as weight gain and

sedation. Some selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and dopamine blockers can reduce some maladaptive behaviors associated with ASD. Although SSRIs reduce levels of repetitive behavior in autistic adults, a 2009 multisite randomized controlled study found no benefit and some adverse effects in children from the SSRI citalopram, raising doubts whether SSRIs are effective for treating repetitive behavior in autistic children.

A further study of related medical reviews determined that the

prescription of SSRI antidepressants for treating autistic spectrum

disorders in children lacked any evidence, and could not be recommended. Reviews of evidence found that the psychostimulant methylphenidate

may be efficacious against hyperactivity and possibly impulsivity

associated with ASD, although the findings were limited by low quality

evidence.

There was no evidence that methylphenidate "has a negative impact on

the core symptoms of ASD, or that it improves social interaction,

stereotypical behaviours, or overall ASD."

Of the many medications studied for treatment of aggressive and

self-injurious behavior in children and adolescents with autism, only

risperidone and methylphenidate demonstrate results that have been

replicated. A 1998 study of the hormone secretin reported improved symptoms and generated tremendous interest, but several controlled studies since have found no benefit. Oxytocin may play a role in autism and may be an effective treatment for repetitive and affiliative behaviors;

two related studies in adults found that oxytocin decreased repetitive

behaviors and improved interpretation of emotions, but these preliminary

results do not necessarily apply to children. An experimental drug STX107 has stopped overproduction of metabotropic glutamate receptor 5

in rodents, and it has been hypothesized that this may help in about 5%

of autism cases, but this hypothesis has not been tested in humans.

Aside from antipsychotics, there is scant reliable research about the effectiveness or safety of drug treatments for adolescents and adults with ASD. Results of the handful of randomized controlled trials that have been performed suggest that risperidone, the SSRI fluvoxamine, and the typical antipsychotic haloperidol may be effective in reducing some behaviors, that haloperidol may be more effective than the tricyclic antidepressant clomipramine, and that the opioid antagonist naltrexone hydrochloride is not effective. In small studies, memantine has been shown to significantly improve language function and social behavior in children with autism. Research is underway on the effects of memantine in adults with autism spectrum disorders. A person with ASD may respond atypically to medications and the medications can have adverse side effects.

Prosthetics

Unlike conventional neuromotor prostheses,

neurocognitive prostheses would sense or modulate neural function in

order to physically reconstitute cognitive processes such as executive function

and language. No neurocognitive prostheses are currently available but

the development of implantable neurocognitive brain-computer interfaces

has been proposed to help treat conditions such as autism.

Affective computing

devices, typically with image or voice recognition capabilities, have

been proposed to help autistic individuals improve their social

communication skills. These devices are still under development. Robots have also been proposed as educational aids for autistic children.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

Transcranial magnetic stimulation, which is a somewhat well established treatment for depression, has been proposed, and used, as a treatment for autism. A review published in 2013 found insufficient evidence to support its widespread use for autism spectrum disorders. A 2015 review found tentative but insufficient evidence to justify its use outside of clinical studies.

Alternative medicine

Acupuncture has not been found to be helpful. A number of naturopathic practitioners claim that CEASE therapy,

a mixture of homeopathy, supplements and 'vaccine detoxing', can help

people with autism however no robust evidence is available for this. A

podiatrist in East Preston, West Sussex was reported to be suggesting the administration of chlorine dioxide, orally and through an enema, to cure children of autism in January 2020. Chlorine dioxide is toxic.

Emerging evidence for mindfulness-based

interventions for improving mental health in adults with autism has

support through a recent systematic review. This includes evidence for

decreasing stress, anxiety, ruminating thoughts, anger, and aggression.

Hyperbaric Oxygen

A boy with ASD, and his father, in a hyperbaric oxygen chamber.

One small 2009 double-blind study of autistic children found that 40

hourly treatments of 24% oxygen at 1.3 atmospheres provided significant

improvement in the children's behavior immediately after treatment

sessions but this study has not been independently confirmed.

More recent, relatively large-scale controlled studies have also

investigated HBOT using treatments of 24% oxygen at 1.3 atmospheres and

have found less promising results. A 2010 double-blind study compared

HBOT to a placebo treatment in children with autistic disorder. Both

direct observational measures of behavioral symptoms and standardized

psychological assessments were used to evaluate the treatment. No

differences were found between the HBOT group and the placebo group on

any of the outcome measures.

A second 2011 single-subject design study also investigated the effects

of 40 HBOT treatments of 24% oxygen at 1.3 atmospheres on directly

observed behaviors using multiple baselines across 16 participants.

Again, no consistent outcomes were observed across any group and

further, no significant improvements were observed within any individual

participant.

Together these studies suggest that HBOT at 24% oxygen at 1.3

atmospheric pressure does not result in a clinically significant

improvement of the behavioral symptoms of autistic disorder.

Nonetheless, news reports and related blogs indicate that HBOT is used

for many cases of children with autism. HBOT can cost up to $150 per

hour with individuals using anywhere from 40 to 120 hours as a part of

their integrated treatment programs. In addition, purchasing (at

$8,495–27,995) and renting ($1,395 per month) of the HBOT chambers is

another option some families use.

When considering the financial and time investments required in order

to participate in this treatment and the inconsistency of the present

findings, HBOT seems to be a riskier and thus, often less favorable

alternative treatment for autism. Further studies are needed in order

for practitioners and families to make more conclusive and valid

decisions concerning HBOT treatments.

Chiropractic

Chiropractic

is an alternative medical practice whose main hypothesis is that

mechanical disorders of the spine affect general health via the nervous

system, and whose main treatment is spinal manipulation. A significant portion of the profession rejects vaccination, as traditional chiropractic philosophy equates vaccines to poison. Most chiropractic writings on vaccination focus on its negative aspects, claiming that it is hazardous, ineffective, and unnecessary, and in some cases suggesting that vaccination causes autism or that chiropractors should be the primary contact for treatment of autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders. Chiropractic treatment has not been shown to be effective for medical conditions other than back pain, and there is insufficient scientific evidence to make conclusions about chiropractic care for autism.

Craniosacral therapy

Craniosacral therapy is an alternative medical practice whose main hypothesis is that restrictions at cranial sutures of the skull affect rhythmic impulses conveyed via cerebrospinal fluid,

and that gentle pressure on external areas can improve the flow and

balance of the supply of this fluid to the brain, relieving symptoms of

many conditions. There is no scientific support for major elements of the underlying model,

there is little scientific evidence to support the therapy, and

research methods that could conclusively evaluate the therapy's

effectiveness have not been applied. No published studies are available on the use of this therapy for autism.

Chelation therapy

Based on the speculation that heavy metal poisoning

may trigger the symptoms of autism, particularly in small subsets of

individuals who cannot excrete toxins effectively, some parents have

turned to alternative medicine practitioners who provide detoxification treatments via chelation therapy. However, evidence to support this practice has been anecdotal and not rigorous. Strong epidemiological evidence refutes links between environmental triggers, in particular thiomersal-containing vaccines,

and the onset of autistic symptoms. No scientific data supports the

claim that the mercury in the vaccine preservative thiomersal causes

autism or its symptoms, and there is no scientific support for chelation therapy as a treatment for autism.

Thiamine

tetrahydrofurfuryl disulfide (TTFD) is hypothesized to act as a

chelating agent in children with autism. A 2002 pilot study administered

TTFD rectally to ten autism spectrum children, and found beneficial clinical effect.

This study has not been replicated, and a 2006 review of thiamine by

the same author did not mention thiamine's possible effect on autism. There is not sufficient evidence to support the use of thiamine (vitamin B1) to treat autism.

Dietary supplements

Many parents give their children dietary supplements

in an attempt to treat autism or to alleviate its symptoms. The range

of supplements given is wide; few are supported by scientific data, but

most have relatively mild side effects.

A review found some low-quality evidence to support the use of vitamin B6 in combination with magnesium at high doses, but the evidence was equivocal and the review noted the possible danger of fatal hypermagnesemia. A Cochrane Review

of the evidence for the use of B6 and magnesium found that "[d]ue to

the small number of studies, the methodological quality of studies, and

small sample sizes, no recommendation can be advanced regarding the use

of B6-Mg as a treatment for autism."

Dimethylglycine (DMG) is hypothesized to improve speech and reduce autistic behaviors, and is a commonly used supplement. Two double-blind, placebo-controlled studies found no statistically significant effect on autistic behaviors, and reported few side effects. No peer-reviewed studies have addressed treatment with the related compound trimethylglycine.

Vitamin C decreased stereotyped behavior in a small 1993 study.

The study has not been replicated, and vitamin C has limited popularity

as an autism treatment. High doses might cause kidney stones or

gastrointestinal upset such as diarrhea.

Probiotics containing potentially beneficial bacteria are hypothesized to relieve some symptoms of autism by minimizing yeast overgrowth in the colon. The hypothesized yeast overgrowth has not been confirmed by endoscopy,

the mechanism connecting yeast overgrowth to autism is only

hypothetical, and no clinical trials to date have been published in the

peer-reviewed literature. No negative side effects have been reported.

Melatonin

is sometimes used to manage sleep problems in developmental disorders.

Adverse effects are generally reported to be mild, including drowsiness,

headache, dizziness, and nausea; however, an increase in seizure

frequency is reported among susceptible children.

Several small RCTs have indicated that melatonin is effective in

treating insomnia in autistic children, but further large studies are

needed.

A 2013 literature review found 20 studies that reported improvements

in sleep parameters as a result of melatonin supplementation, and

concluded that "the administration of exogenous melatonin for abnormal

sleep parameters in ASD is evidence-based."

Although omega-3 fatty acids, which are polyunsaturated fatty acids

(PUFA), are a popular treatment for children with ASD, there is very

little high-quality scientific evidence supporting their effectiveness, and further research is needed.

Several other supplements have been hypothesized to relieve autism symptoms, including BDTH2, carnosine, cholesterol, cyproheptadine, D-cycloserine, folic acid, glutathione, metallothionein promoters, other PUFA such as omega-6 fatty acids, tryptophan, tyrosine, thiamine (see Chelation therapy), vitamin B12, and zinc. These lack reliable scientific evidence of efficacy or safety in treatment of autism.

Diets

Atypical eating behavior occurs in about three-quarters of children

with ASD, to the extent that it was formerly a diagnostic indicator.

Selectivity is the most common problem, although eating rituals and food

refusal also occur; this does not appear to result in malnutrition. Although some children with autism also have gastrointestinal

(GI) symptoms, there is a lack of published rigorous data to support

the theory that autistic children have more or different GI symptoms

than usual; studies report conflicting results, and the relationship between GI problems and ASD is unclear.

In the early 1990s, it was hypothesized that autism can be caused or aggravated by opioid peptides like casomorphine that are metabolic products of gluten and casein.

Based on this hypothesis, diets that eliminate foods containing either

gluten or casein, or both, are widely promoted, and many testimonials

can be found describing benefits in autism-related symptoms, notably

social engagement and verbal skills. Studies supporting these claims

have had significant flaws, so these data are inadequate to guide

treatment recommendations.

Other elimination diets have also been proposed, targeting salicylates, food dyes, yeast,

and simple sugars. No scientific evidence has established the efficacy

of such diets in treating autism in children. An elimination diet may

create nutritional deficiencies that harm overall health unless care is

taken to assure proper nutrition.

For example, a 2008 study found that autistic boys on casein-free diets

have significantly thinner bones than usual, presumably because the

diets contribute to calcium and vitamin D deficiencies.

Electroconvulsive therapy

Studies indicate that 12–17% of adolescents and young adults with autism satisfy diagnostic criteria for catatonia, which is loss of or hyperactive motor activity. Electroconvulsive therapy

(ECT) has been used to treat cases of catatonia and related conditions

in people with autism. However, no controlled trials have been performed

of ECT in autism, and there are serious ethical and legal obstacles to

its use.

Stem cell therapy

Mesenchymal stem cells and cord blood CD34+ cells have been proposed to treat autism, but this proposal has not been tested. They may represent a future treatment.

Since immune system deregulation has been implicated in autism,

mesenchymal stem cells show the greatest promise as treatment for the

disorder. Changes in the innate and adaptive immune system have been

observed. Those with autism show an imbalance in CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ T

cells, as well as in NK cells. In addition, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) overproduce IL-1β. MSC mediated immune suppressive activity could restore this immune imbalance.

Religious interventions

The Table Talk of Martin Luther contains the story of a twelve-year-old boy who some believe was severely autistic. According to Luther's notetaker Mathesius, Luther thought the boy was a soulless mass of flesh possessed by the devil, and suggested that he be suffocated. In 2003, an autistic boy in Wisconsin suffocated during an exorcism by an Evangelical minister in which he was wrapped in sheets.

Ultraorthodox Jewish parents sometimes use spiritual and mystical

interventions such as prayers, blessings, recitations of religious

text, amulets, changing the child's name, and exorcism.

One study has suggested that spirituality and not religious activities involving the mothers of autistic children were associated with better outcomes for the child.

Anti-cure perspective

The exact cause of autism

is unclear, yet some organizations advocate researching a cure. Some

autism rights organizations view autism as a way of life rather than as a

mental disorder and thus advocate acceptance over a search for a cure.

Historical approach

Before

autism was well understood, children in Britain and America would often

be put in institutions on the instruction of doctors and the parents

told to forget about them. Observer journalist Christopher Stevens,

father of an autistic child, reports how a British doctor told him that

after a child was admitted, usually "nature would take its course" and

the child would die due to the prevalence of tuberculosis.

Research

Environmental enrichment has found to be useful in animal models of autism. Two human trials also found benefit in some children.

Between the 1950s and 1970s LSD was studied, however, has not been studied since.