Prior to European colonization of the Americas, indigenous peoples used controlled burns to modify the landscape. The controlled fires were part of the environmental cycles and maintenance of wildlife habitats that sustained the cultures and economies of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. What was initially perceived by colonists as "untouched, pristine" wilderness in North America was actually the cumulative result of those occasional managed fires creating an intentional mosaic of grasslands and forests across North America, sustained and managed by the original Peoples of the landbase.

Radical disruption of Indigenous burning practices occurred with European colonization and forced relocation of those who had historically maintained the landscape. Some colonists understood the traditional use and potential benefits of low-intensity broadcast burns ("Indian-type" fires), but others feared and suppressed them. In the 1880s, impacts of colonization had devastated indigenous populations, and fire exclusion had become more widespread. By the early 20th century, fire suppression had become the official US federal policy. Understanding pre-colonization land management and the traditional knowledge held by the Indigenous peoples who practiced it provides an important basis for current re-engagement with the landscape and is critical for the correct interpretation of the ecological basis for vegetation distribution.

Human-shaped landscape

Authors such as William Henry Hudson, Longfellow, Francis Parkman, and Thoreau contributed to the widespread myth that pre-Columbian North America was a pristine, natural wilderness, "a world of barely perceptible human disturbance.” At the time of these writings, however, enormous tracts of land had already been allowed to succeed to climax due to the reduction in anthropogenic fires after the depopulation of Native peoples from epidemics of diseases introduced by Europeans in the 16th century, forced relocation, and warfare. Prior to the arrival of Europeans, Native Americans had played a major role in determining the diversity of their ecosystems.

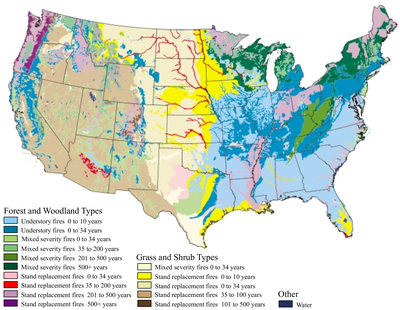

The most significant type of environmental change brought about by Precolumbian human activity was the modification of vegetation. [...] Vegetation was primarily altered by the clearing of forest and by intentional burning. Natural fires certainly occurred but varied in frequency and strength in different habitats. Anthropogenic fires, for which there is ample documentation, tended to be more frequent but weaker, with a different seasonality than natural fires, and thus had a different type of influence on vegetation. The result of clearing and burning was, in many regions, the conversion of forest to grassland, savanna, scrub, open woodland, and forest with grassy openings. (William M. Denevan)

Fire was used to keep large areas of forest and mountains free of undergrowth for hunting or travel, or to create berry patches.

Grasslands and savannas

When first encountered by Europeans, many ecosystems were the result of repeated fires every one to three years, resulting in the replacement of forests with grassland or savanna, or opening up the forest by removing undergrowth. Terra preta soils, created by slow burning, are found mainly in the Amazon basin, where estimates of the area covered range from 0.1 to 0.3%, or 6,300 to 18,900 km² of low forested Amazonia to 1.0% or more.

There is some argument about the effect of human-caused burning when compared to lightning in western North America. As Emily Russell (1983) has pointed out, “There is no strong evidence that Indians purposely burned large areas....The presence of Indians did, however, undoubtedly increase the frequency of fires above the low numbers caused by lightning.” As might be expected, Indian fire use had its greatest impact “in local areas near Indian habitations.”

Reasons for and benefits of burning

Reasons given for controlled burns in pre-contact ecosystems are numerous and well thought out. They include:

- Facilitating agriculture by rapidly recycling mineral-rich ash and biomass.

- Increasing nut production in wild/wildcrafted orchards by darkening the soil layer with carbonized leaf litter, decreasing localized albedo, and increasing the average temperature in spring, when nut flowers and buds would be sensitive to late frosts.

- Promoting the regrowth of fire-adapted food and utility plants by initiating seed germination or coppicing – shrub species like osier, willow, hazel, Rubus, and others have their lifespan extended and productivity increased through controlled cutting (burning) of branch stems.

- Facilitating hunting by clearing underbrush and fallen limbs, allowing for more silent passage and stalking through the forest, as well as increasing visibility of game and clear avenues for projectiles.

- Facilitating travel by reducing impassible brambles, underbrush and thickets.

- Decreasing the risk of larger scale, catastrophic fires which consume decades of built-up fuel.

- Increasing population of game animals by creating habitat in grasslands or increasing understory habitat of fire-adapted grass forage (in other words, wildcrafted pasturage) for deer, lagomorphs, bison, extinct grazing megafauna like mammoths, rhinoceros, camelids and others, the nearly extinct prairie chicken; and the populations of nut-consuming species like rodents, turkey and bear and notably the passenger pigeon through increased nut production (above); as well as the populations of their predators, i.e. mountain lions, lynx, bobcats, wolves, etc.

- Increasing the frequency of regrowth of beneficial food and medicine plants, like clearing-adapted species like cherry, plum, and others.

- Decreasing tick and biting insect populations by destroying overwintering instars and eggs.

- Smoke density cools river temperatures and decreases evapotranspiration by plants, which increases river flow.

- Rivers cooled by smoke density alert salmon that they may begin upstream migration.

Impacts of European settlement

By the time that European explorers first arrived in North America, millions of acres of "natural" landscapes were already manipulated and maintained for human use. Fires indicated the presence of humans to many European explorers and settlers arriving on ship. In San Pedro Bay in 1542, chaparral fires provided that signal to Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, and later to others across all of what would be named California.

In the American west, it is estimated that 184,737 hectares (465,495 aces) burned annually pre-settlement in what is now Oregon and Washington.

By the 17th century, native populations were on the verge of collapse due to the genocidal structure of settler colonialism. Many colonists often either deliberately set wildfires and/or allowed out of control fires to "run free." Also, sheep and cattle owners, as well as shepherds and cowboys, often set the alpine meadows and prairies on fire at the end of the grazing season to burn the dried grasses, reduce brush, and kill young trees, as well as encourage the growth of new grasses for the following summer and fall grazing season. Changes in management regimes had subsequent changes in Native American diets, along with the introduction of alcohol has also had profound negative effects on indigenous communities. As Native people were forced off their traditional landbases or killed, traditional land management practices were abandoned and were eventually made illegal by settler governance.

By the 19th century, many Indigenous nations had been forced to sign treaties with the federal government and relocate to reservations, which were sometimes hundreds of miles away from their ancestral homelands. In addition to violent and forced removal, fire suppression would become part of colonial methods of removal and genocide. As sociologist Kari Norgaard has shown, "Fire suppression was mandated by the very first session of the California Legislature in 1850 during the apex of genocide in the northern part of the state." For example, the Karuk peoples of Northern California "burn [the forest] to enhance the quality of forest food species like elk, deer, acorns, mushrooms, and lilies, as well as basketry materials such as hazel and willow, but also keep travel routes open.” When such relationships to their environment were made illegal through fire suppression, it would have dramatic consequences on their methods of relating to one another, their environment, their food sources, and their educational practices. Thus, many scholars have argued that fire suppression can be seen as a form of "Colonial Ecological Violence," "which results in particular risks and harms experienced by Native peoples and communities."

Through the turn of the 20th century, settlers continued to use fire to clear the land of brush and trees in order to make new farm land for crops and new pastures for grazing animals – the North American variation of slash and burn technology – while others deliberately burned to reduce the threat of major fires – the so‑called "light burning" technique. Light burning is also been called "Paiute forestry," a direct but derogatory reference to southwestern tribal burning habits. The ecological impacts of settler fires were vastly different than those of their Native American predecessors, and further, Native fire practices were largely made illegal at the beginning of the 20th Century with the passage of the Weeks Act in 1911.

Altered fire regimes

Removal of indigenous populations and their controlled burning practices have resulted in major ecological changes, including increased severity of wild fires, especially in combination with Climate change. Attitudes towards Native American-type burning have shifted in recent times, and Tribal agencies and organizations, now with fewer restrictions placed on them by the colonists, have resumed their traditional use of fire practices in a modern context by reintroducing fire to fire-adapted ecosystems, on and adjacent to, tribal lands. Many foresters and ecologists have also recognized the importance of Native fire practices. They are now learning from traditional fire practitioners and using controlled burns to reduce fuel accumulations, change species composition, and manage vegetation structure and density for healthier forests and rangelands.