The Medieval Warm Period (MWP), also known as the Medieval Climate Optimum or the Medieval Climatic Anomaly, was a time of warm climate in the North Atlantic region that lasted from c. 950 to c. 1250. Climate proxy records show peak warmth occurred at different times for different regions, which indicate that the MWP was not a globally uniform event. Some refer to the MWP as the Medieval Climatic Anomaly to emphasize that climatic effects other than temperature were also important.

The MWP was followed by a regionally cooler period in the North Atlantic and elsewhere, which is sometimes called the Little Ice Age (LIA).

Possible causes of the MWP include increased solar activity, decreased volcanic activity, and changes in ocean circulation.

Research

The Medieval Warm Period (MWP) is generally thought to have occurred from c. 950 – c. 1250, during the European Middle Ages. In 1965, Hubert Lamb, one of the first paleoclimatologists, published research based on data from botany, historical document research, and meteorology, combined with records indicating prevailing temperature and rainfall in England around c. 1200 and around c. 1600. He proposed, "Evidence has been accumulating in many fields of investigation pointing to a notably warm climate in many parts of the world, that lasted a few centuries around c. 1000 – c. 1200 AD, and was followed by a decline of temperature levels till between c. 1500 and c. 1700 the coldest phase since the last ice age occurred."

The era of warmer temperatures became known as the Medieval Warm Period and the subsequent cold period the Little Ice Age (LIA). However, the view that the MWP was a global event was challenged by other researchers. The IPCC First Assessment Report of 1990 discussed the "Medieval Warm Period around 1000 AD (which may not have been global) and the Little Ice Age which ended only in the middle to late nineteenth century." It stated that temperatures in the "late tenth to early thirteenth centuries (about AD 950–1250) appear to have been exceptionally warm in western Europe, Iceland and Greenland." The IPCC Third Assessment Report from 2001 summarized newer research: "evidence does not support globally synchronous periods of anomalous cold or warmth over this time frame, and the conventional terms of 'Little Ice Age' and 'Medieval Warm Period' are chiefly documented in describing northern hemisphere trends in hemispheric or global mean temperature changes in past centuries."

Global temperature records taken from ice cores, tree rings, and lake deposits have shown that the Earth may have been slightly cooler globally (by 0.03 °C) than in the early and the mid-20th century.

Palaeoclimatologists developing region-specific climate reconstructions of past centuries conventionally label their coldest interval as "LIA" and their warmest interval as the "MWP". Others follow the convention, and when a significant climate event is found in the "LIA" or "MWP" timeframes, they associate their events to the period. Some "MWP" events are thus wet events or cold events, rather than strictly warm events, particularly in central Antarctica, where climate patterns that are opposite to those of the North Atlantic have been noticed.

Global climate during the Medieval Warm Period

In 2019, by using an extended proxy data set, the Pages-2k consortium confirmed that the Medieval Climate Anomaly was not a globally synchronous event. The warmest 51-year period within the MWP did not occur at the same time in different regions. They argue for a regional instead of global framing of climate variability in the preindustrial Common Era to aid in understanding.

North Atlantic

Lloyd D. Keigwin's 1996 study of radiocarbon-dated box core data from marine sediments in the Sargasso Sea found that its sea surface temperature was approximately 1 °C (1.8 °F) cooler approximately 400 years ago, during the LIA, and 1700 years ago and was approximately 1 °C warmer 1000 years ago, during the MWP.

Using sediment samples from Puerto Rico, the Gulf Coast, and the Atlantic Coast from Florida to New England, Mann et al. (2009) found consistent evidence of a peak in North Atlantic tropical cyclone activity during the MWP, which was followed by a subsequent lull in activity.

Iceland

Iceland was first settled between about 865 and 930, during a time believed to be warm enough for sailing and farming. By retrieval and isotope analysis of marine cores and from examination of mollusc growth patterns from Iceland, Patterson et al. reconstructed a stable oxygen (δ18 O) and carbon (δ13 C) isotope record at a decadal resolution from the Roman Warm Period to the MWP and the LIA. Patterson et al. conclude that the summer temperature stayed high but winter temperature decreased after the initial settlement of Iceland.

Greenland

The 2009 Mann et al. study found warmth exceeding 1961–1990 levels in southern Greenland and parts of North America during the MWP, which the study defines as from 950 to 1250, with warmth in some regions exceeding temperatures of the 1990–2010 period. Much of the Northern Hemisphere showed a significant cooling during the LIA, which the study defines as from 1400 to 1700, but Labrador and isolated parts of the United States appeared to be approximately as warm as during the 1961–1990 period.

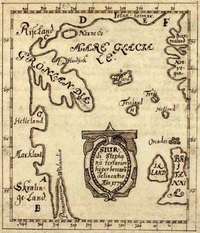

The Norse colonization of the Americas has been associated with warmer periods. The common theory is that Norsemen took advantage of ice-free seas to colonize areas in Greenland and other outlying lands of the far north. However, a study from Columbia University suggests that Greenland was not colonized in warmer weather, but the warming effect in fact lasted for only very briefly. c. 1000AD, the climate was sufficiently warm for the Vikings to journey to Newfoundland and to establish a short-lived outpost there.

In around 985, Vikings founded the Eastern and Western Settlements, both near the southern tip of Greenland. In the colony's early stages, they kept cattle, sheep, and goats, with around a quarter of their diet from seafood. After the climate became colder and stormier around 1250, their diet steadily shifted towards ocean sources. By around 1300, seal hunting provided over three quarters of their food.

By 1350, there was reduced demand for their exports, and trade with Europe fell away. The last document from the settlements dates from 1412, and over the following decades, the remaining Europeans left in what seems to have been a gradual withdrawal, which was caused mainly by economic factors such as increased availability of farms in Scandinavian countries.

Europe

Substantial glacial retreat in southern Europe was experienced during the MWP. While several smaller glaciers experienced complete deglaciation, larger glaciers in the region survived and now provide insight into the region’s climate history. In addition to warming induced glacial melt, sedimentary records reveal a period of increased flooding, coinciding with the MWP, in eastern Europe that is attributed to enhanced precipitation from a positive phase North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). Other impacts of climate change can be less apparent such as a changing landscape. Preceding the MWP, a coastal region in western Sardinia was abandoned by the Romans. The coastal area was able to substantially expand into the lagoon without the influence of human populations and a high stand during the MWP. When human populations returned to the region, they encountered a land altered by climate change and had to reestablish ports.

Other regions

North America

In Chesapeake Bay (now in Maryland and Virginia, United States), researchers found large temperature excursions (changes from the mean temperature of that time) during the MWP (about 950–1250) and the Little Ice Age (about 1400–1700, with cold periods persisting into the early 20th century), which are possibly related to changes in the strength of North Atlantic thermohaline circulation. Sediments in Piermont Marsh of the lower Hudson Valley show a dry MWP from 800 to 1300.

Prolonged droughts affected many parts of what is now the Western United States, especially eastern California and the west of Great Basin. Alaska experienced three intervals of comparable warmth: 1–300, 850–1200, and since 1800. Knowledge of the MWP in North America has been useful in dating occupancy periods of certain Native American habitation sites, especially in arid parts of the Western United States. Droughts in the MWP may have impacted Native American settlements also in the Eastern United States, such as at Cahokia. Review of more recent archaeological research shows that as the search for signs of unusual cultural changes has broadened, some of the early patterns (such as violence and health problems) have been found to be more complicated and regionally varied than had been previously thought. Other patterns, such as settlement disruption, deterioration of long-distance trade, and population movements, have been further corroborated.

Africa

The climate in equatorial eastern Africa has alternated between being drier than today and relatively wet. The climate was drier during the MWP (1000–1270). Off the coast of Africa, Isotopic analysis of bones from the Canary Islands’ inhabitants during the MWP to LIA transition reveal the region experienced a 5 °C decrease in air temperature. Over this period, the diet of inhabitants did not appreciably change, which suggests they were remarkably resilient to climate change.

Antarctica

A sediment core from the eastern Bransfield Basin, in the Antarctic Peninsula, preserves climatic events from both the LIA and the MWP. The authors noted, "The late Holocene records clearly identify Neoglacial events of the LIA and Medieval Warm Period (MWP)." Some Antarctic regions were atypically cold, but others were atypically warm between 1000 and 1200.

Pacific Ocean

Corals in the tropical Pacific Ocean suggest that relatively cool and dry conditions may have persisted early in the millennium, which is consistent with a La Niña-like configuration of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation patterns.

In 2013, a study from three US universities was published in Science magazine and showed that the water temperature in the Pacific Ocean was 0.9 degrees warmer during the MWP than during the LIA and 0.65 degrees warmer than the decades before the study.

South America

The MWP has been noted in Chile in a 1500-year lake bed sediment core, as well as in the Eastern Cordillera of Ecuador.

A reconstruction, based on ice cores, found that the MWP could be distinguished in tropical South America from about 1050 to 1300 and was followed in the 15th century by the LIA. Peak temperatures did not rise as to the level of the late 20th century, which were unprecedented in the area during the study period of 1600 years.

Asia

Adhikari and Kumon (2001), investigating sediments in Lake Nakatsuna, in central Japan, found a warm period from 900 to 1200 that corresponded to the MWP and three cool phases, two of which could be related to the LIA. Other research in northeastern Japan showed that there was one warm and humid interval, from 750 to 1200, and two cold and dry intervals, from 1 to 750 and from 1200 to now. Ge et al. studied temperatures in China for the past 2000 years and found high uncertainty prior to the 16th century but good consistency over the last 500 years highlighted by the two cold periods, 1620s–1710s and 1800s–1860s, and the 20th-century warming. They also found that the warming from the 10th to the 14th centuries in some regions might be comparable in magnitude to the warming of the last few decades of the 20th century, which was unprecedented within the past 500 years. Generally, a warming period was identified in China, coinciding with the MWP, using multi-proxy data for temperature. However, the warming was inconsistent across China. Significant temperature change, from the MWP to LIA, was found for northeast and central-east China but not for northwest China and the Tibetan Plateau. Alongside an overall warmer climate, areas in Asia experienced wetter conditions in the MWP southeastern China, India, and far eastern Russia. Peat cores from peatland in southeast China suggest changes in the East Asian Summer Monsoon (EASM) and El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) are responsible for increased precipitation in the region during the MWP. The Indian Summer Monsoon (ISM) was also enhanced during the MWP with a temperature driven change to the Atlantic Multi-decadal Oscillation (AMO), bringing more precipitation to India. In far eastern Russia, continental regions experienced severe floods during the MWP while nearby islands experienced less precipitation leading to a decrease in peatland. Pollen data from this region indicates an expansion of warm climate vegetation with an increasing number of broadleaf and decreasing number of coniferous forests.

Oceania

There is an extreme scarcity of data from Australia for both the MWP and the LIA. However, evidence from wave-built shingle terraces for a permanently-full Lake Eyre during the 9th and the 10th centuries is consistent with a La Niña-like configuration, but the data are insufficient to show how lake levels varied from year to year or what climatic conditions elsewhere in Australia were like.

A 1979 study from the University of Waikato found, "Temperatures derived from an 18O/16O profile through a stalagmite found in a New Zealand cave (40.67°S, 172.43°E) suggested the Medieval Warm Period to have occurred between AD c. 1050 and c. 1400 and to have been 0.75 °C warmer than the Current Warm Period." More evidence in New Zealand is from an 1100-year tree-ring record.