From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A space elevator is conceived as a cable fixed to the equator and reaching into space. A counterweight at the upper end keeps the center of mass well above geostationary orbit level. This produces enough upward centrifugal force from Earth's rotation to fully counter the downward gravity, keeping the cable upright and taut. Climbers carry cargo up and down the cable.

A space elevator is a proposed type of space transportation system.[1] Its main component is a ribbon-like cable (also called a tether) anchored to the surface and extending into space. It is designed to permit vehicle transport along the cable from a planetary surface, such as the Earth's, directly into space or orbit, without the use of large rockets. An Earth-based space elevator would consist of a cable with one end attached to the surface near the equator and the other end in space beyond geostationary orbit (35,800 km altitude). The competing forces of gravity, which is stronger at the lower end, and the outward/upward centrifugal force, which is stronger at the upper end, would result in the cable being held up, under tension, and stationary over a single position on Earth. Once deployed, the tether would be ascended repeatedly by mechanical means to orbit, and descended to return to the surface from orbit.[2]

The concept of a space elevator was first published in 1895 by Konstantin Tsiolkovsky.[3] His proposal was for a free-standing tower reaching from the surface of Earth to the height of geostationary orbit. Like all buildings, Tsiolkovsky's structure would be under compression, supporting its weight from below. Since 1959, most ideas for space elevators have focused on purely tensile structures, with the weight of the system held up from above. In the tensile concepts, a space tether reaches from a large mass (the counterweight) beyond geostationary orbit to the ground. This structure is held in tension between Earth and the counterweight like an upside-down plumb bob.

On Earth, with its relatively strong gravity, current technology is not capable of manufacturing tether materials that are sufficiently strong and light to build a space elevator. However, recent concepts for a space elevator are notable for their plans to use materials based on carbon nanotube or boron nitride nanotube as the tensile element in the tether design. The measured strengths of those nanotube molecules are high compared to their linear densities. They hold promise as materials to make an Earth-based space elevator possible.[2]

The concept is also applicable to other planets and celestial bodies. For locations in the solar system with weaker gravity than Earth's (such as the Moon or Mars), the strength-to-density requirements are not as great for tether materials. Currently available materials (such as Kevlar) are strong and light enough that they could be used as the tether material for elevators there.[4]

History

Early concepts

The key concept of the space elevator appeared in 1895 when Russian scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky was inspired by the Eiffel Tower in Paris. He considered a similar tower that reached all the way into space and was built from the ground up to the altitude of 35,790 kilometers, the height of geostationary orbit.[5] He noted that the top of such a tower would be circling Earth as in a geostationary orbit. Objects would attain horizontal velocity as they rode up the tower, and an object released at the tower's top would have enough horizontal velocity to remain there in geostationary orbit. Tsiolkovsky's conceptual tower was a compression structure, while modern concepts call for a tensile structure (or "tether").

20th century

Building a compression structure from the ground up proved an unrealistic task as there was no material in existence with enough compressive strength to support its own weight under such conditions.[6] In 1959 another Russian scientist, Yuri N. Artsutanov, suggested a more feasible proposal. Artsutanov suggested using a geostationary satellite as the base from which to deploy the structure downward. By using a counterweight, a cable would be lowered from geostationary orbit to the surface of Earth, while the counterweight was extended from the satellite away from Earth, keeping the cable constantly over the same spot on the surface of the Earth. Artsutanov's idea was introduced to the Russian-speaking public in an interview published in the Sunday supplement of Komsomolskaya Pravda in 1960,[7] but was not available in English until much later. He also proposed tapering the cable thickness so that the stress in the cable was constant. This gives a thinner cable at ground level that becomes thicker up towards GSO.Both the tower and cable ideas were proposed in the quasi-humorous Ariadne column in New Scientist, December 24, 1964.

In 1966, Isaacs, Vine, Bradner and Bachus, four American engineers, reinvented the concept, naming it a "Sky-Hook," and published their analysis in the journal Science.[8] They decided to determine what type of material would be required to build a space elevator, assuming it would be a straight cable with no variations in its cross section, and found that the strength required would be twice that of any then-existing material including graphite, quartz, and diamond.

In 1975 an American scientist, Jerome Pearson, reinvented the concept yet again, publishing his analysis in the journal Acta Astronautica. He designed[9] a tapered cross section that would be better suited to building the elevator. The completed cable would be thickest at the geostationary orbit, where the tension was greatest, and would be narrowest at the tips to reduce the amount of weight per unit area of cross section that any point on the cable would have to bear. He suggested using a counterweight that would be slowly extended out to 144,000 kilometers (89,000 miles), almost half the distance to the Moon as the lower section of the elevator was built. Without a large counterweight, the upper portion of the cable would have to be longer than the lower due to the way gravitational and centrifugal forces change with distance from Earth. His analysis included disturbances such as the gravitation of the Moon, wind and moving payloads up and down the cable.

The weight of the material needed to build the elevator would have required thousands of Space Shuttle trips, although part of the material could be transported up the elevator when a minimum strength strand reached the ground or be manufactured in space from asteroidal or lunar ore.

In 1979, space elevators were introduced to a broader audience with the simultaneous publication of Arthur C. Clarke's novel, The Fountains of Paradise, in which engineers construct a space elevator on top of a mountain peak in the fictional island country of Taprobane (loosely based on Sri Lanka, albeit moved south to the Equator), and Charles Sheffield's first novel, The Web Between the Worlds, also featuring the building of a space elevator. Three years later, in Robert A. Heinlein's 1982 novel Friday the principal character makes use of the "Nairobi Beanstalk" in the course of her travels. In Kim Stanley Robinson's 1993 novel Red Mars, colonists build a space elevator on Mars that allows both for more colonists to arrive and also for natural resources mined there to be able to leave for Earth. In David Gerrold's 2000 novel, Jumping Off The Planet, a family excursion up the Ecuador "beanstalk" is actually a child-custody kidnapping. Gerrold's book also examines some of the industrial applications of a mature elevator technology. In a biological version, Joan Slonczewski's novel The Highest Frontier depicts a college student ascending a space elevator constructed of self-healing cables of anthrax bacilli. The engineered bacteria can regrow the cables when severed by space debris.

After the development of carbon nanotubes in the 1990s, engineer David Smitherman of NASA/Marshall's Advanced Projects Office realized that the high strength of these materials might make the concept of a space elevator feasible, and put together a workshop at the Marshall Space Flight Center, inviting many scientists and engineers to discuss concepts and compile plans for an elevator to turn the concept into a reality.

In 2000, another American scientist, Bradley C. Edwards, suggested creating a 100,000 km (62,000 mi) long paper-thin ribbon using a carbon nanotube composite material.[10] He chose the wide-thin ribbon-like cross-section shape rather than earlier circular cross-section concepts because that shape would stand a greater chance of surviving impacts by meteoroids. The ribbon cross-section shape also provided large surface area for climbers to climb with simple rollers. Supported by the NASA Institute for Advanced Concepts, Edwards' work was expanded to cover the deployment scenario, climber design, power delivery system, orbital debris avoidance, anchor system, surviving atomic oxygen, avoiding lightning and hurricanes by locating the anchor in the western equatorial Pacific, construction costs, construction schedule, and environmental hazards.[2][11][12][13]

21st century

To speed space elevator development, proponents have organized several competitions, similar to the Ansari X Prize, for relevant technologies.[14][15] Among them are Elevator:2010, which organized annual competitions for climbers, ribbons and power-beaming systems from 2005 to 2009, the Robogames Space Elevator Ribbon Climbing competition,[16] as well as NASA's Centennial Challenges program, which, in March 2005, announced a partnership with the Spaceward Foundation (the operator of Elevator:2010), raising the total value of prizes to US$400,000.[17][18] The first European Space Elevator Challenge (EuSEC) to establish a climber structure took place in August 2011.[19]In 2005, "the LiftPort Group of space elevator companies announced that it will be building a carbon nanotube manufacturing plant in Millville, New Jersey, to supply various glass, plastic and metal companies with these strong materials. Although LiftPort hopes to eventually use carbon nanotubes in the construction of a 100,000 km (62,000 mi) space elevator, this move will allow it to make money in the short term and conduct research and development into new production methods."[20] Their announced goal was a space elevator launch in 2010. On February 13, 2006 the LiftPort Group announced that, earlier the same month, they had tested a mile of "space-elevator tether" made of carbon-fiber composite strings and fiberglass tape measuring 5 cm (2.0 in) wide and 1 mm (approx. 13 sheets of paper) thick, lifted with balloons.[21]

In 2007, Elevator:2010 held the 2007 Space Elevator games, which featured US$500,000 awards for each of the two competitions, (US$1,000,000 total) as well as an additional US$4,000,000 to be awarded over the next five years for space elevator related technologies.[22] No teams won the competition, but a team from MIT entered the first 2-gram (0.07 oz), 100-percent carbon nanotube entry into the competition.[23] Japan held an international conference in November 2008 to draw up a timetable for building the elevator.[24]

In 2008 the book Leaving the Planet by Space Elevator by Dr. Brad Edwards and Philip Ragan was published in Japanese and entered the Japanese best-seller list.[25] This led to Shuichi Ono, chairman of the Japan Space Elevator Association, unveiled a space-elevator plan, putting what observers considered an extremely low cost estimate of a trillion yen (£5 billion/ $8 billion) to build one.[24]

In 2012, the Obayashi Corporation announced that in 38 years it could build a space elevator using carbon nanotube technology.[26] At 200 kilometers per hour, the design's 30-passenger climber would be able to reach the GEO level after a 7.5 day trip.[27] No cost estimates, finance plans, or other specifics were made. This, along with timing and other factors, hinted that the announcement was made largely to provide publicity for the opening of one of the company's other projects in Tokyo.[28]

Google said in April 2014 that it has considered designing a space elevator, but that the project was not then feasible.[29]

Physics of space elevators

Apparent gravitational field

A space elevator cable rotates along with the rotation of the Earth. Therefore, objects attached to the cable will experience upward centrifugal force in the direction opposing the downward gravitational force. The higher up the cable the object is located, the less the gravitational pull of the Earth, and the stronger the upward centrifugal force due to the rotation, so that more centrifugal force opposes less gravity. The centrifugal force and the gravity are balanced at GEO. Above GEO, the centrifugal force is stronger than gravity, causing objects attached to the cable there to pull upward on it.The net force for objects attached to the cable is called the apparent gravitational field. The apparent gravitational field for attached objects is the (downward) gravity minus the (upward) centrifugal force. The apparent gravity experienced by an object on the cable is zero at GEO, downward below GEO, and upward above GEO.

The apparent gravitational field can be represented this way:

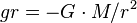

- The downward force of actual gravity decreases with height:

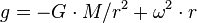

- The upward centrifugal force due to the planet's rotation increases with height:

- Together, the apparent gravitational field is the sum of the two:

- g is the acceleration of apparent gravity, pointing down (negative) or up (positive) along the vertical cable (m s−2),

- gr is the gravitational acceleration due to Earth's pull, pointing down (negative)(m s−2),

- a is the centrifugal acceleration, pointing up (positive) along the vertical cable (m s−2),

- G is the gravitational constant (m3 s−2 kg−1)

- M is the mass of the Earth (kg)

- r is the distance from that point to Earth's center (m),

- ω is Earth's rotation speed (radian/s).

On the cable below geostationary orbit, downward gravity is greater than the upward centrifugal force, so the apparent gravity pulls objects attached to the cable downward. Any object released from the cable below that level will initially accelerate downward along the cable. Then gradually it will deflect eastward from the cable. On the cable above the level of stationary orbit, upward centrifugal force is greater than downward gravity, so the apparent gravity pulls objects attached to the cable upward. Any object released from the cable above the geosynchronous level will initially accelerate upward along the cable. Then gradually it will deflect westward from the cable.

Cable section

Historically, the main technical problem has been considered the ability of the cable to hold up, with tension, the weight of itself below any given point. The greatest tension on a space elevator cable is at the point of geostationary orbit, 35,786 km (22,236 mi) above the Earth's equator. This means that the cable material, combined with its design, must be strong enough to hold up its own weight from the surface up to 35,786 km (22,236 mi). A cable which is thicker in cross section at that height than at the surface could better hold up its own weight over a longer length. How the cross section area tapers from the maximum at 35,786 km (22,236 mi) to the minimum at the surface is therefore an important design factor for a space elevator cable.To maximize the usable excess strength for a given amount of cable material, the cable's cross section area will need to be designed for the most part in such a way that the stress (i.e., the tension per unit of cross sectional area) is constant along the length of the cable.[30][31] The constant-stress criterion is a starting point in the design of the cable cross section as it changes with altitude. Other factors considered in more detailed designs include thickening at altitudes where more space junk is present, consideration of the point stresses imposed by climbers, and the use of varied materials.[32] To account for these and other factors, modern detailed cross section designs seek to achieve the largest safety margin possible, with as little variation over altitude and time as possible.[32] In simple starting-point designs, that equates to constant-stress.

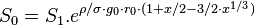

In the constant-stress case, the cross-section follows this differential equation:

or

: Ref[30] equation 6

: Ref[30] equation 6

- g is the acceleration along the radius (m·s−2),

- S is the cross-section area of the cable at any given point r, (m2) and dS its variation (m2 as well),

- ρ is the density of the material used for the cable (kg·m−3).

- σ is the stress the cross-section area can bear without yielding (N·m−2=kg·m−1·s−2), its elastic limit.

![\Delta\left[ \ln (S)\right]{}_{r_0}^{r_1} = -\rho/\sigma \cdot \Delta\left[ G \cdot M/r + \omega^2 \cdot r^2/2 \right]{}_{r_0}^{r_1}](//upload.wikimedia.org/math/4/b/5/4b5e77fa1980d888cd567af02e0ab5f7.png) ,

,

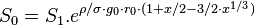

Between these two points, this quantity can be expressed as:

![\Delta\left[ \ln (S)\right] = \rho/\sigma \cdot g_0 \cdot r_0 \cdot ( 1 + x/2 - 3/2 \cdot x^{1/3} )](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/6/3/7/63768d5eb7a064a9c5a773031dab6ecc.png) , or

, or : Ref[30] equation 7

: Ref[30] equation 7

is the ratio between the centrifugal force on the equator and the gravitational force.[30]

is the ratio between the centrifugal force on the equator and the gravitational force.[30]Cable material

The free breaking length can be used to compare materials: it is the length of an un-tapered cylindrical cable at which it will break under its own weight under constant gravity. For a given material, that length is σ/ρ/g0. The free breaking length needed is given by the equation![\Delta\left[ \ln (S)\right] = \rho/\sigma \cdot g_0 \cdot r_0 \cdot ( 1 + x/2 - 3/2 \cdot x^{1/3} )](//upload.wikimedia.org/math/6/3/7/63768d5eb7a064a9c5a773031dab6ecc.png) , where

, where

Structure

There are a variety of space elevator designs. Almost every design includes a base station, a cable, climbers, and a counterweight. Earth's rotation creates upward centrifugal force on the counterweight. The counterweight is held down by the cable while the cable is held up and taut by the counterweight. The base station anchors the whole system to the surface of the Earth. Climbers climb up and down the cable with cargo.

Base station

Modern concepts for the base station/anchor are typically mobile stations, large oceangoing vessels or other mobile platforms. Mobile base stations have the advantage over the earlier stationary concepts (with land-based anchors) by being able to maneuver to avoid high winds, storms, and space debris. Oceanic anchor points are also typically in international waters, simplifying and reducing cost of negotiating territory use for the base station.[2]Stationary land based platforms have simpler and less costly logistical access to the base. They also have an advantage of being able to be at high altitude, such as on top of mountains, or even potentially on high towers. This reduces influence from the atmosphere and how deep down into the Earth's gravity field the cable needs to extend, and so fractionally reduces the critical strength-to-density requirements for the cable material, all other design factors being equal.[6]

Cable

A space elevator cable must carry its own weight as well as the additional weight of climbers. The required strength of the cable will vary along its length. This is because at various points it has to carry the weight of the cable below, or provide a downward force to retain the cable and counterweight above. Maximum tension on a space elevator cable is at geosynchronous altitude so the cable must be thickest there and taper carefully as it approaches Earth. Any potential cable design may be characterized by the taper factor – the ratio between the cable's radius at geosynchronous altitude and at the Earth's surface.[33]

The cable must be made of a material with a large tensile strength/density ratio. For example, the Edwards space elevator design assumes a cable material with a specific strength of at least 100,000 kN/(kg/m).[2] This value takes into consideration the entire weight of the space elevator. An untapered space elevator cable would need a material capable of sustaining a length of 4,960 kilometers (3,080 mi) of its own weight at sea level to reach a geostationary altitude of 35,786 km (22,236 mi) without yielding.[34] Therefore, a material with very high strength and lightness is needed.

For comparison, metals like titanium, steel or aluminium alloys have breaking lengths of only 20–30 km. Modern fibre materials such as kevlar, fibreglass and carbon/graphite fibre have breaking lengths of 100–400 km. Nanoengineered materials such as carbon nanotubes and, more recently discovered, graphene ribbons (perfect two-dimensional sheets of carbon) are expected to have breaking lengths of 5000–6000 km at sea level, and also are able to conduct electrical power.[citation needed]

For high specific strength, carbon has advantages because it is only the 6th element in the periodic table. Carbon has comparatively few of the protons and neutrons which contribute most of the dead weight of any material. Most of the interatomic bonding forces of any element are contributed by only the outer few electrons. For carbon, the strength and stability of those bonds is high compared to the mass of the atom. The challenge in using carbon nanotubes remains to extend to macroscopic sizes the production of such material that are still perfect on the microscopic scale (as microscopic defects are most responsible for material weakness). [35] [36] [37] [38] As of 2014, carbon nanotube technology allowed growing tubes up to a few tenths of meters.[39]

Climbers

A space elevator cannot be an elevator in the typical sense (with moving cables) due to the need for the cable to be significantly wider at the center than at the tips. While various designs employing moving cables have been proposed, most cable designs call for the "elevator" to climb up a stationary cable.

Climbers cover a wide range of designs. On elevator designs whose cables are planar ribbons, most propose to use pairs of rollers to hold the cable with friction.

Climbers must be paced at optimal timings so as to minimize cable stress and oscillations and to maximize throughput. Lighter climbers can be sent up more often, with several going up at the same time. This increases throughput somewhat, but lowers the mass of each individual payload.[40]

The horizontal speed, i.e. due to orbital rotation, of each part of the cable increases with altitude, proportional to distance from the center of the Earth, reaching low orbital speed at a point approximately 66 percent of the height between the surface and geostationary orbit (a height of about 23,400 km). A payload released at this point will go into a highly eccentric elliptical orbit, staying just barely clear from atmospheric reentry, with the periapsis at the same altitude as LEO and the apoapsis at the release height. With increasing release height the orbit becomes less eccentric as both periapsis and apoapsis increase, becoming circular at geostationary level.[41][42] When the payload has reached GEO, the horizontal speed is exactly the speed of a circular orbit at that level, so that if released, it would remain adjacent to that point on the cable. The payload can also continue climbing further up the cable beyond GEO, allowing it to obtain higher speed at jettison. If released from 100,000 km, the payload would have enough speed to reach the asteroid belt.[32]

As a payload is lifted up a space elevator, it gains not only altitude, but horizontal speed (angular momentum) as well. The angular momentum is taken from the Earth's rotation. As the climber ascends, it is initially moving slower than each successive part of cable it is moving on to. This is the coriolis force: the climber "drags" (Westward) on the cable, as it climbs, and slightly decreases the Earth's rotation speed. The opposite process occurs for descending payloads: the cable is tilted eastwards, thus slightly increasing Earth's rotation speed.

The overall effect of the centrifugal force acting on the cable causes it to constantly try to return to the energetically favorable vertical orientation, so after an object has been lifted on the cable the counterweight will swing back towards the vertical like an inverted pendulum.[40] Space elevators and their loads will be designed so that the center of mass is always well-enough above the level of geostationary orbit[43] to hold up the whole system. Lift and descent operations must be carefully planned so as to keep the pendulum-like motion of the counterweight around the tether point under control.[44]

Climber speed is limited by the Coriolis force, available power, and by the need to ensure the climber's accelerating force does not break the cable. Climbers also need to maintain a minimum average speed in order to move material up and down economically and expeditiously.[citation needed] At the speed of a very fast car or train of 300 km/h (190 mph) it will take about 5 days to climb to geosynchronous orbit.[45]

Powering climbers

Both power and energy are significant issues for climbers—the climbers need to gain a large amount of potential energy as quickly as possible to clear the cable for the next payload.Various methods have been proposed to get that energy to the climber:

- Transfer the energy to the climber through wireless energy transfer while it is climbing.

- Transfer the energy to the climber through some material structure while it is climbing.

- Store the energy in the climber before it starts – requires an extremely high specific energy such as nuclear energy.

- Solar power – power compared to the weight of panels limits the speed of climb.[46]

Yoshio Aoki, a professor of precision machinery engineering at Nihon University and director of the Japan Space Elevator Association, suggested including a second cable and using the conductivity of carbon nanotubes to provide power.[24]

Counterweight

Several solutions have been proposed to act as a counterweight:- a heavy, captured asteroid;[5]

- a space dock, space station or spaceport positioned past geostationary orbit; or

- a further upward extension of the cable itself so that the net upward pull is the same as an equivalent counterweight;

- parked spent climbers that had been used to thicken the cable during construction, other junk, and material lifted up the cable for the purpose of increasing the counterweight.[32]

Launching into deep space

An object attached to a space elevator at a radius of approximately 53,100 km will be at escape velocity when released. Transfer orbits to the L1 and L2 Lagrangian points can be attained by release at 50,630 and 51,240 km, respectively, and transfer to lunar orbit from 50,960 km.[47]At the end of Pearson's 144,000 km (89,000 mi) cable, the tangential velocity is 10.93 kilometers per second (6.79 mi/s). That is more than enough to escape Earth's gravitational field and send probes at least as far out as Jupiter. Once at Jupiter, a gravitational assist maneuver permits solar escape velocity to be reached.[30]

Extraterrestrial elevators

A space elevator could also be constructed on other planets, asteroids and moons.A Martian tether could be much shorter than one on Earth. Mars' surface gravity is 38 percent of Earth's, while it rotates around its axis in about the same time as Earth. Because of this, Martian stationary orbit is much closer to the surface, and hence the elevator would be much shorter. Current materials are already sufficiently strong to construct such an elevator.[48] Building a Martian elevator would be complicated by the Martian moon Phobos, which is in a low orbit and intersects the Equator regularly (twice every orbital period of 11 h 6 min).

On the near side of the Moon, the strength-to-density required of the tether of a lunar space elevator exists in currently available materials. A lunar space elevator would be about 50,000 kilometers (31,000 mi) long. Since the Moon does not rotate fast enough, there is no effective lunar-stationary orbit, but the Lagrangian points could be used. The near side would extend through the Earth-Moon L1 point from an anchor point near the center of the visible part of Earth's Moon.[49]

On the far side of the Moon, a lunar space elevator would need to be very long—more than twice the length of an Earth elevator—but due to the low gravity of the Moon, can also be made of existing engineering materials.[49]

Rapidly spinning asteroids or moons could use cables to eject materials to convenient points, such as Earth orbits;[50] or conversely, to eject materials to send a portion of the mass of the asteroid or moon to Earth orbit or a Lagrangian point. Freeman Dyson, a physicist and mathematician, has suggested[citation needed] using such smaller systems as power generators at points distant from the Sun where solar power is uneconomical.

A space elevator using presently available engineering materials could be constructed between mutually tidally locked worlds, such as Pluto and Charon or the components of binary asteroid Antiope, with no terminus disconnect, according to Francis Graham of Kent State University.[51] However, spooled variable lengths of cable must be used due to ellipticity of the orbits.

Construction

The construction of a space elevator would need reduction of some technical risk. Some advances in engineering, manufacturing and physical technology are required.[2] Once a first space elevator is built, the second one and all others would have the use of the previous ones to assist in construction, making their costs considerably lower. Such follow-on space elevators would also benefit from the great reduction in technical risk achieved by the construction of the first space elevator.[2]Prior to the work of Edwards in 2000[10] most concepts for constructing a space elevator had the cable manufactured in space. That was thought to be necessary for such a large and long object and for such a large counterweight. Manufacturing the cable in space would be done in principle by using an asteroid or Near-Earth object for source material.[52][53] These earlier concepts for construction require a large preexisting space-faring infrastructure to maneuver an asteroid into its needed orbit around Earth. They also require the development of technologies for manufacture in space of large quantities of exacting materials.[54]

Since 2001, most work has focused on simpler methods of construction requiring much smaller space infrastructures. They conceive the launch of a long cable on a large spool, then deployment of it in space.[2][10][54] The spool is initially parked in a geostationary orbit above the planned anchor point. When a long cable is dropped "downward" (toward Earth), it is balanced by a mass being dropped "upward" (away from Earth) for the whole system to remain on the geosynchronous orbit. Earlier designs imagined the balancing mass to be another cable (with counterweight) extending upward, with the main spool remaining at the original geosynchronous orbit level. Most current designs elevate the spool itself as the main cable is paid out, a simpler process. When the lower end of the cable is so long as to reach the Earth (at the equator), it can be anchored. Once anchored, the center of mass is elevated more (by adding mass at the upper end or by paying out more cable). This adds more tension to the whole cable, which can then be used as an elevator cable.

One plan for construction uses conventional rockets to place a "minimum size" initial seed cable of only 19,800 kg.[2] This first very small ribbon would be adequate to support the first 619 kg climber. The first 207 climbers would carry up and attach more cable to the original, increasing its cross section area and widening the initial ribbon to about 160 mm wide at its widest point. The result would be a 750-ton cable with a lift capacity of 20 tons per climber.

Safety issues and construction challenges

For early systems, transit times from the surface to the level of geosynchronous orbit would be about five days. On these early systems, the time spent moving through the Van Allen radiation belts would be enough that passengers would need to be protected from radiation by shielding, which adds mass to the climber and decreases payload.[55]A space elevator would present a navigational hazard, both to aircraft and spacecraft. Aircraft could be diverted by air-traffic control restrictions. All objects in stable orbits that have perigee below the maximum altitude of the cable that are not synchronous with the cable will impact the cable eventually, unless avoiding action is taken. One potential solution proposed by Edwards is to use a movable anchor (a sea anchor) to allow the tether to "dodge" any space debris large enough to track.[2]

Impacts by space objects such as meteoroids, micrometeorites and orbiting man-made debris, pose another design constraint on the cable. A cable would need to be designed to maneuver out of the way of debris, or absorb impacts of small debris without breaking.

Economics

With a space elevator, materials might be sent into orbit at a fraction of the current cost. As of 2000, conventional rocket designs cost about US$25,000 per kilogram (US$11,000 per pound) for transfer to geostationary orbit.[56] Current proposals envision payload prices starting as low as $220 per kilogram ($100 per pound),[57] similar to the $5–$300/kg estimates of the Launch loop, but higher than the $310/ton to 500 km orbit quoted[58] to Dr. Jerry Pournelle for an orbital airship system.Philip Ragan, co-author of the book "Leaving the Planet by Space Elevator", states that "The first country to deploy a space elevator will have a 95 percent cost advantage and could potentially control all space activities."[59]

Related concepts

The conventional current concept of a "Space Elevator" has evolved from a static compressive structure reaching to the level of GEO, to the modern baseline idea of a static tensile structure anchored to the ground and extending to well above the level of GEO. In the current usage by practitioners (and in this article), a "Space Elevator" means the Tsiolkovsky-Artsutanov-Pearson type as considered by the International Space Elevator Consortium. This conventional type is a static structure fixed to the ground and extending into space high enough that cargo can climb the structure up from the ground to a level where simple release will put the cargo into an orbit.[60]Some concepts related to this modern baseline are not usually termed a "Space Elevator", but are similar in some way and are sometimes termed "Space Elevator" by their proponents. For example, Hans Moravec published an article in 1977 called "A Non-Synchronous Orbital Skyhook" describing a concept using a rotating cable.[61] The rotation speed would exactly match the orbital speed in such a way that the tip velocity at the lowest point was zero compared to the object to be "elevated". It would dynamically grapple and then "elevate" high flying objects to orbit or low orbiting objects to higher orbit. Other ideas use very tall compressive towers to reduce the demands on launch vehicles.[62] The vehicle is "elevated" up the tower, which may extend as high as above the atmosphere, and is launched from the top.

The original concept envisioned by Tsiolkovsky was a compression structure, a concept similar to an aerial mast. While such structures might reach space (100 km, 62 mi), they are unlikely to reach geostationary orbit. The concept of a Tsiolkovsky tower combined with a classic space elevator cable (reaching above the level of GEO) has been suggested.[6]

A tall tower[63] to access near-space altitudes of 20 km (12 mi) has been proposed by Canadian researchers. The structure would be pneumatically supported and free standing with control systems guiding the structure's center of mass. Proposed uses include tourism and commerce, communications, wind generation and low-cost space launch.[62]

Other concepts related to a space elevator (or parts of a space elevator) include an orbital ring, a pneumatic space tower,[64][65] a space fountain, a launch loop, a Skyhook, a space tether, and a buoyant "SpaceShaft".[66]

: Ref

: Ref![\Delta\left[ \ln (S)\right]{}_{r_0}^{r_1} = -\rho/\sigma \cdot \Delta\left[ G \cdot M/r + \omega^2 \cdot r^2/2 \right]{}_{r_0}^{r_1}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/4/b/5/4b5e77fa1980d888cd567af02e0ab5f7.png) ,

, : Ref

: Ref