From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Protein design is the

rational design of new

protein molecules to design novel activity, behavior, or purpose, and to advance basic understanding of protein function

[1]. Proteins can be designed from scratch (

de novo design) or by making calculated variants of a known protein structure and its sequence (termed

protein redesign).

Rational protein design

approaches make protein-sequence predictions that will fold to specific

structures. These predicted sequences can then be validated

experimentally through methods such as

peptide synthesis,

site-directed mutagenesis, or

artificial gene synthesis.

Rational protein design dates back to the mid-1970s, although initial

protein design approaches were based mostly on sequence composition and

did not account for specific interactions between side-chains at the

atomic level.

[2] Recently, however, improvements in molecular force fields, protein design algorithms, and

structural bioinformatics, such as

libraries of amino acid conformations,

have enabled the development of advanced computational protein design

tools. These computational tools can make complex calculations on

protein energetics and flexibility, and perform searches over vast

configuration spaces,

which would be unfeasible to perform manually. Due to the development

of computational protein design programs, and important successes in the

field (see

examples below), rational protein design has become one of the most important tools in

protein engineering.

Overview and history

The goal in rational protein design is to predict

amino acid sequences that will

fold

to a specific protein structure. Although the number of possible

protein sequences is vast, growing exponentially with the size of the

protein chain, only a subset of them will fold reliably and quickly to

one

native state. Protein design involves identifying novel sequences within this subset. The native state of a protein is the conformational

free energy

minimum for the chain. Thus, protein design is the search for sequences

that have the chosen structure as a free energy minimum. In a sense, it

is the reverse of

protein structure prediction. In design, a

tertiary structure is specified, and a sequence that will fold to it is identified. Hence, it is also termed

inverse folding.

Protein design is then an optimization problem: using some scoring

criteria, an optimized sequence that will fold to the desired structure

is chosen.

When the first proteins were rationally designed during the 1970s and

1980s, the sequence for these was optimized manually based on analyses

of other known proteins, the sequence composition, amino acid charges,

and the geometry of the desired structure.

[2]

The first designed proteins are attributed to Bernd Gutte, who designed

a reduced version of a known catalyst, bovine ribonuclease, and

tertiary structures consisting of beta-sheets and alpha-helices,

including a binder of

DDT. Urry and colleagues later designed

elastin-like

fibrous

peptides based on rules on sequence composition. Richardson and

coworkers designed a 79-residue protein with no sequence homology to a

known protein.

[2] In the 1990s, the advent of powerful computers,

libraries of amino acid conformations, and force fields developed mainly for

molecular dynamics

simulations enabled the development of structure-based computational

protein design tools. Following the development of these computational

tools, great success has been achieved over the last 30 years in protein

design. The first protein successfully designed completely

de novo was done by

Stephen Mayo and coworkers in 1997,

[3] and, shortly after, in 1999

Peter S. Kim and coworkers designed dimers, trimers, and tetramers of unnatural right-handed

coiled coils.

[4][5] In 2003,

David Baker's laboratory designed a full protein to a fold never seen before in nature.

[6] Later, in 2008, Baker's group computationally designed enzymes for two different reactions.

[7]

In 2010, one of the most powerful broadly neutralizing antibodies was

isolated from patient serum using a computationally designed protein

probe.

[8] Due to these and other successes (e.g., see

examples below), protein design has become one of the most important tools available for

protein engineering. There is great hope that the design of new proteins, small and large, will have uses in

biomedicine and

bioengineering.

Underlying models of protein structure and function

Protein design programs use

computer models of the molecular forces that drive proteins in

in vivo

environments. In order to make the problem tractable, these forces are

simplified by protein design models. Although protein design programs

vary greatly, they have to address four main modeling questions: What is

the target structure of the design, what flexibility is allowed on the

target structure, which sequences are included in the search, and which

force field will be used to score sequences and structures.

Target structure

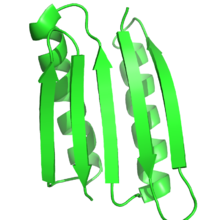

The

Top7 protein was one of the first proteins designed for a fold that had never been seen before in nature

[6]

Protein function is heavily dependent on protein structure, and

rational protein design uses this relationship to design function by

designing proteins that have a target structure or fold. Thus, by

definition, in rational protein design the target structure or ensemble

of structures must be known beforehand. This contrasts with other forms

of protein engineering, such as

directed evolution, where a variety of methods are used to find proteins that achieve a specific function, and with

protein structure prediction where the sequence is known, but the structure is unknown.

Most often, the target structure is based on a known structure of

another protein. However, novel folds not seen in nature have been made

increasingly possible. Peter S. Kim and coworkers designed trimers and

tetramers of unnatural coiled coils, which had not been seen before in

nature.

[4][5] The protein Top7, developed in

David Baker's lab, was designed completely using protein design algorithms, to a completely novel fold.

[6] More recently, Baker and coworkers developed a series of principles to design ideal

globular-protein structures based on

protein folding funnels

that bridge between secondary structure prediction and tertiary

structures. These principles, which build on both protein structure

prediction and protein design, were used to design five different novel

protein topologies.

[9]

Sequence space

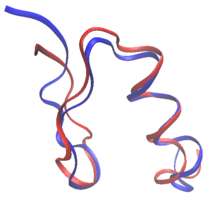

FSD-1 (shown in blue, PDB id: 1FSV) was the first

de novo computational design of a full protein.

[3]

The target fold was that of the zinc finger in residues 33–60 of the

structure of protein Zif268 (shown in red, PDB id: 1ZAA). The designed

sequence had very little sequence identity with any known protein

sequence.

In rational protein design, proteins can be redesigned from the

sequence and structure of a known protein, or completely from scratch in

de novo protein design. In protein redesign, most of the

residues in the sequence are maintained as their wild-type amino-acid

while a few are allowed to mutate. In

de novo design, the entire sequence is designed anew, based on no prior sequence.

Both

de novo designs and protein redesigns can establish rules on the

sequence space:

the specific amino acids that are allowed at each mutable residue

position. For example, the composition of the surface of the

RSC3 probe

to select HIV-broadly neutralizing antibodies was restricted based on

evolutionary data and charge balancing. Many of the earliest attempts on

protein design were heavily based on empiric

rules on the sequence space.

[2] Moreover, the

design of fibrous proteins usually follows strict rules on the sequence space.

Collagen-based designed proteins, for example, are often composed of Gly-Pro-X repeating patterns.

[2] The advent of computational techniques allows designing proteins with no human intervention in sequence selection.

[3]

Structural flexibility

Common protein design programs use rotamer libraries to simplify the

conformational space of protein side chains. This animation loops

through all the rotamers of the isoleucine amino acid based on the

Penultimate Rotamer Library.

[10]

In protein design, the target structure (or structures) of the

protein are known. However, a rational protein design approach must

model some

flexibility on the target structure in order to

increase the number of sequences that can be designed for that structure

and to minimize the chance of a sequence folding to a different

structure. For example, in a protein redesign of one small amino acid

(such as alanine) in the tightly packed core of a protein, very few

mutants would be predicted by a rational design approach to fold to the

target structure, if the surrounding side-chains are not allowed to be

repacked.

Thus, an essential parameter of any design process is the amount of

flexibility allowed for both the side-chains and the backbone. In the

simplest models, the protein backbone is kept rigid while some of the

protein side-chains are allowed to change conformations. However,

side-chains can have many degrees of freedom in their bond lengths, bond

angles, and

χ dihedral angles.

To simplify this space, protein design methods use rotamer libraries

that assume ideal values for bond lengths and bond angles, while

restricting

χ dihedral angles to a few oft-observed low-energy conformations termed

rotamers.

Rotamer libraries describe rotamers based on an analysis of many

protein structures. Backbone-independent rotamer libraries describe all

rotamers.

[10]

Backbone-dependent rotamer libraries, in contrast, describe the

rotamers as how likely they are to appear depending on the protein

backbone arrangement around the side chain.

[11]

The rotamers described by rotamer libraries are usually regions in

space. Most protein design programs use one conformation (e.g., the

modal value for rotamer dihedrals in space) or several points in the

region described by the rotamer; the

OSPREY protein design program, in contrast, models the entire continuous region.

[12]

Although rational protein design must preserve the general backbone

fold a protein, allowing some backbone flexibility can significantly

increase the number of sequences that fold to the structure while

maintaining the general fold of the protein.

[13]

Backbone flexibility is especially important in protein redesign

because sequence mutations often result in small changes to the backbone

structure. Moreover, backbone flexibility can be essential for more

advanced applications of protein design, such as binding prediction and

enzyme design. Some models of protein design backbone flexibility

include small and continuous global backbone movements, discrete

backbone samples around the target fold, backrub motions, and protein

loop flexibility.

[13][14]

Energy function

Comparison of various potential energy functions. The most accurate

energy are those that use quantum mechanical calculations, but these are

too slow for protein design. On the other extreme, heuristic energy

functions, are based on statistical terms and are very fast. In the

middle are molecular mechanics energy functions that are

physically-based but are not as computationally expensive as quantum

mechanical simulations.

[15]

Rational protein design techniques must be able to discriminate

sequences that will be stable under the target fold from those that

would prefer other low-energy competing states. Thus, protein design

requires accurate

energy functions

that can rank and score sequences by how well they fold to the target

structure. At the same time, however, these energy functions must

consider the computational

challenges

behind protein design. One of the most challenging requirements for

successful design is an energy function that is both accurate and simple

for computational calculations.

The most accurate energy functions are those based on quantum

mechanical simulations. However, such simulations are too slow and

typically impractical for protein design. Instead, many protein design

algorithms use either physics-based energy functions adapted from

molecular mechanics simulation programs,

knowledge based energy-functions, or a hybrid mix of both. The trend has been toward using more physics-based potential energy functions.

[15]

Physics-based energy functions, such as

AMBER and

CHARMM,

are typically derived from quantum mechanical simulations, and

experimental data from thermodynamics, crystallography, and

spectroscopy.

[16]

These energy functions typically simplify physical energy function and

make them pairwise decomposable, meaning that the total energy of a

protein conformation can be calculated by adding the pairwise energy

between each atom pair, which makes them attractive for optimization

algorithms. Physics-based energy functions typically model an

attractive-repulsive

Lennard-Jones term between atoms and a pairwise

electrostatics coulombic term

[17] between non-bonded atoms.

Water-mediated hydrogen bonds play a key role in protein–protein

binding. One such interaction is shown between residues D457, S365 in

the heavy chain of the HIV-broadly-neutralizing antibody VRC01 (green)

and residues N58 and Y59 in the HIV envelope protein GP120 (purple).

[18]

Statistical potentials, in contrast to physics-based potentials, have

the advantage of being fast to compute, of accounting implicitly of

complex effects and being less sensitive to small changes in the protein

structure.

[19] These energy functions are

based on deriving energy values from frequency of appearance on a structural database.

Protein design, however, has requirements that can sometimes be

limited in molecular mechanics force-fields. Molecular mechanics

force-fields, which have been used mostly in molecular dynamics

simulations, are optimized for the simulation of single sequences, but

protein design searches through many conformations of many sequences.

Thus, molecular mechanics force-fields must be tailored for protein

design. In practice, protein design energy functions often incorporate

both statistical terms and physics-based terms. For example, the Rosetta

energy function, one of the most-used energy functions, incorporates

physics-based energy terms originating in the CHARMM energy function,

and statistical energy terms, such as rotamer probability and

knowledge-based electrostatics. Typically, energy functions are highly

customized between laboratories, and specifically tailored for every

design.

[16]

Challenges for effective design energy functions

Water

makes up most of the molecules surrounding proteins and is the main

driver of protein structure. Thus, modeling the interaction between

water and protein is vital in protein design. The number of water

molecules that interact with a protein at any given time is huge and

each one has a large number of degrees of freedom and interaction

partners. Instead, protein design programs model most of such water

molecules as a continuum, modeling both the hydrophobic effect and

solvation polarization.

[16]

Individual water molecules can sometimes have a crucial structural

role in the core of proteins, and in protein–protein or protein–ligand

interactions. Failing to model such waters can result in mispredictions

of the optimal sequence of a protein–protein interface. As an

alternative, water molecules can be added to rotamers.

As an optimization problem

This animation illustrates the complexity of a protein design search,

which typically compares all the rotamer-conformations from all possible

mutations at all residues. In this example, the residues Phe36 and His

106 are allowed to mutate to, respectively, the amino acids Tyr and Asn.

Phe and Tyr have 4 rotamers each in the rotamer library, while Asn and

His have 7 and 8 rotamers, respectively, in the rotamer library (from

the Richardson's penultimate rotamer library

[10]).

The animation loops through all (4 + 4) x (7 + 8) = 120 possibilities.

The structure shown is that of myoglobin, PDB id: 1mbn.

The goal of protein design is to find a protein sequence that will

fold to a target structure. A protein design algorithm must, thus,

search all the conformations of each sequence, with respect to the

target fold, and rank sequences according to the lowest-energy

conformation of each one, as determined by the protein design energy

function. Thus, a typical input to the protein design algorithm is the

target fold, the sequence space, the structural flexibility, and the

energy function, while the output is one or more sequences that are

predicted to fold stably to the target structure.

The number of candidate protein sequences, however, grows

exponentially with the number of protein residues; for example, there

are 20

100 protein sequences of length 100. Furthermore, even if amino acid side-chain conformations are limited to a few rotamers (see

Structural flexibility),

this results in an exponential number of conformations for each

sequence. Thus, in our 100 residue protein, and assuming that each amino

acid has exactly 10 rotamers, a search algorithm that searches this

space will have to search over 200

100 protein conformations.

The most common energy functions can be decomposed into pairwise

terms between rotamers and amino acid types, which casts the problem as a

combinatorial one, and powerful optimization algorithms can be used to

solve it. In those cases, the total energy of each conformation

belonging to each sequence can be formulated as a sum of individual and

pairwise terms between residue positions. If a designer is interested

only in the best sequence, the protein design algorithm only requires

the lowest-energy conformation of the lowest-energy sequence. In these

cases, the amino acid identity of each rotamer can be ignored and all

rotamers belonging to different amino acids can be treated the same. Let

ri be a rotamer at residue position

i in the protein chain, and

E(r

i) the potential energy between the internal atoms of the rotamer. Let

E(

ri,

rj) be the potential energy between

ri and rotamer

rj at residue position

j. Then, we define the optimization problem as one of finding the conformation of minimum energy (

ET):

![\min E_{{T}}=\sum _{{i}}{\Big [}E_{i}(r_{i})+\sum _{{i\neq j}}E_{{ij}}(r_{i},r_{j}){\Big ]}\,](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3332d826843218136390cef20e4ee8e3694fc477)

|

|

(1)

|

The problem of minimizing

ET is an

NP-hard problem.

[14][20][21]

Even though the class of problems is NP-hard, in practice many

instances of protein design can be solved exactly or optimized

satisfactorily through heuristic methods.

Algorithms

Several

algorithms have been developed specifically for the protein design

problem. These algorithms can be divided into two broad classes: exact

algorithms, such as

dead-end elimination, that lack

runtime guarantees but guarantee the quality of the solution; and

heuristic

algorithms, such as Monte Carlo, that are faster than exact algorithms

but have no guarantees on the optimality of the results. Exact

algorithms guarantee that the optimization process produced the optimal

according to the protein design model. Thus, if the predictions of exact

algorithms fail when these are experimentally validated, then the

source of error can be attributed to the energy function, the allowed

flexibility, the sequence space or the target structure.

Some protein design algorithms are listed below. Although these

algorithms address only the most basic formulation of the protein design

problem, Equation (

1),

when the optimization goal changes because designers introduce

improvements and extensions to the protein design model, such as

improvements to the structural flexibility allowed (e.g., protein

backbone flexibility) or including sophisticated energy terms, many of

the extensions on protein design that improve modeling are built atop

these algorithms. For example, Rosetta Design incorporates sophisticated

energy terms, and backbone flexibility using Monte Carlo as the

underlying optimizing algorithm. OSPREY's algorithms build on the

dead-end elimination algorithm and A* to incorporate continuous backbone

and side-chain movements. Thus, these algorithms provide a good

perspective on the different kinds of algorithms available for protein

design.

With mathematical guarantees

Dead-end elimination

The dead-end elimination (DEE) algorithm reduces the search space of

the problem iteratively by removing rotamers that can be provably shown

to be not part of the global lowest energy conformation (GMEC). On each

iteration, the dead-end elimination algorithm compares all possible

pairs of rotamers at each residue position, and removes each rotamer

r′i that can be shown to always be of higher energy than another rotamer

ri and is thus not part of the GMEC:

Other powerful extensions to the dead-end elimination algorithm include the

pairs elimination criterion, and the

generalized dead-end elimination criterion. This algorithm has also been extended to handle continuous rotamers with provable guarantees.

Although the Dead-end elimination algorithm runs in polynomial time

on each iteration, it cannot guarantee convergence. If, after a certain

number of iterations, the dead-end elimination algorithm does not prune

any more rotamers, then either rotamers have to be merged or another

search algorithm must be used to search the remaining search space. In

such cases, the dead-end elimination acts as a pre-filtering algorithm

to reduce the search space, while other algorithms, such as A*, Monte

Carlo, Linear Programming, or FASTER are used to search the remaining

search space.

[14]

Branch and bound

The protein design conformational space can be represented as a

tree, where the protein residues are ordered in an arbitrary way, and the tree branches at each of the rotamers in a residue.

Branch and bound algorithms use this representation to efficiently explore the conformation tree: At each

branching, branch and bound algorithms

bound the conformation space and explore only the promising branches.

[14][23][24]

A popular search algorithm for protein design is the

A* search algorithm.

[14][24]

A* computes a lower-bound score on each partial tree path that lower

bounds (with guarantees) the energy of each of the expanded rotamers.

Each partial conformation is added to a priority queue and at each

iteration the partial path with the lowest lower bound is popped from

the queue and expanded. The algorithm stops once a full conformation has

been enumerated and guarantees that the conformation is the optimal.

The A* score

f in protein design consists of two parts,

f=g+h.

g is the exact energy of the rotamers that have already been assigned in the partial conformation.

h is a lower bound on the energy of the rotamers that have not yet been assigned. Each is designed as follows, where

d is the index of the last assigned residue in the partial conformation.

![h=\sum _{{j=d+1}}^{n}[\min _{{r_{j}}}(E(r_{j})+\sum _{{i=1}}^{d}E(r_{i},r_{j})+\sum _{{k=j+1}}^{n}\min _{{r_{k}}}E(r_{j},r_{k}))]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e143d714d94f81766d65c1ab49da42eeeed08b4a)

Integer linear programming

The problem of optimizing

ET (Equation (

1)) can be easily formulated as an

integer linear program (ILP).

[25]

One of the most powerful formulations uses binary variables to

represent the presence of a rotamer and edges in the final solution, and

constraints the solution to have exactly one rotamer for each residue

and one pairwise interaction for each pair of residues:

s.t.

ILP solvers, such as

CPLEX, can compute the exact optimal solution for large instances of protein design problems. These solvers use a

linear programming relaxation of the problem, where

qi and

qij are allowed to take continuous values, in combination with a

branch and cut

algorithm to search only a small portion of the conformation space for

the optimal solution. ILP solvers have been shown to solve many

instances of the side-chain placement problem.

[25]

Message-passing based approximations to the linear programming dual

ILP solvers depend on linear programming (LP) algorithms, such as the

Simplex or

barrier-based

methods to perform the LP relaxation at each branch. These LP

algorithms were developed as general-purpose optimization methods and

are not optimized for the protein design problem (Equation (

1)). In consequence, the LP relaxation becomes the bottleneck of ILP solvers when the problem size is large.

[26] Recently, several alternatives based on

message-passing algorithms

have been designed specifically for the optimization of the LP

relaxation of the protein design problem. These algorithms can

approximate both the

dual or the

primal

instances of the integer programming, but in order to maintain

guarantees on optimality, they are most useful when used to approximate

the dual of the protein design problem, because approximating the dual

guarantees that no solutions are missed. Message-passing based

approximations include the

tree reweighted max-product message passing algorithm,

[27][28] and the

message passing linear programming algorithm.

[29]

Optimization algorithms without guarantees

Monte Carlo and simulated annealing

Monte

Carlo is one of the most widely used algorithms for protein design. In

its simplest form, a Monte Carlo algorithm selects a residue at random,

and in that residue a randomly chosen rotamer (of any amino acid) is

evaluated.

[21] The new energy of the protein,

Enew is compared against the old energy

Eold and the new rotamer is

accepted with a probability of:

where

β is the

Boltzmann constant and the temperature

T can be chosen such that in the initial rounds it is high and it is slowly

annealed to overcome local minima.

[12]

FASTER

The

FASTER algorithm uses a combination of deterministic and stochastic

criteria to optimize amino acid sequences. FASTER first uses DEE to

eliminate rotamers that are not part of the optimal solution. Then, a

series of iterative steps optimize the rotamer assignment.

[30][31]

Belief propagation

In

belief propagation for protein design, the algorithm exchanges messages that describe the

belief

that each residue has about the probability of each rotamer in

neighboring residues. The algorithm updates messages on every iteration

and iterates until convergence or until a fixed number of iterations.

Convergence is not guaranteed in protein design. The message

mi→ j(rj that a residue

i sends to every rotamer

(rj at neighboring residue

j is defined as:

Both max-product and sum-product belief propagation have been used to optimize protein design.

Applications and examples of designed proteins

Enzyme design

The design of new

enzymes

is a use of protein design with huge bioengineering and biomedical

applications. In general, designing a protein structure can be different

from designing an enzyme, because the design of enzymes must consider

many states involved in the

catalytic mechanism. However protein design is a prerequisite of

de novo

enzyme design because, at the very least, the design of catalysts

requires a scaffold in which the catalytic mechanism can be inserted.

[32]

Great progress in

de novo enzyme design, and redesign, was

made in the first decade of the 21st century. In three major studies,

David Baker and coworkers

de novo designed enzymes for the retro-

aldol reaction,

[33] a Kemp-elimination reaction,

[34] and for the

Diels-Alder reaction.

[35]

Furthermore, Stephen Mayo and coworkers developed an iterative method

to design the most efficient known enzyme for the Kemp-elimination

reaction.

[36] Also, in the laboratory of

Bruce Donald, computational protein design was used to switch the specificity of one of the

protein domains of the

nonribosomal peptide synthetase that produces

Gramicidin S, from its natural substrate

phenylalanine

to other noncognate substrates including charged amino acids; the

redesigned enzymes had activities close to those of the wild-type.

[37]

Design for affinity

Protein–protein interactions are involved in most biotic processes. Many of the hardest-to-treat diseases, such as

Alzheimer's, many forms of

cancer (e.g.,

TP53), and human immunodeficiency virus (

HIV)

infection involve protein–protein interactions. Thus, to treat such

diseases, it is desirable to design protein or protein-like therapeutics

that bind one of the partners of the interaction and, thus, disrupt the

disease-causing interaction. This requires designing

protein-therapeutics for

affinity toward its partner.

Protein–protein interactions can be designed using protein design

algorithms because the principles that rule protein stability also rule

protein–protein binding. Protein–protein interaction design, however,

presents challenges not commonly present in protein design. One of the

most important challenges is that, in general, the interfaces between

proteins are more polar than protein cores, and binding involves a

tradeoff between desolvation and hydrogen bond formation.

[38]

To overcome this challenge, Bruce Tidor and coworkers developed a

method to improve the affinity of antibodies by focusing on

electrostatic contributions. They found that, for the antibodies

designed in the study, reducing the desolvation costs of the residues in

the interface increased the affinity of the binding pair.

[38][39][40]

Scoring binding predictions

Protein

design energy functions must be adapted to score binding predictions

because binding involves a trade-off between the lowest-

energy conformations of the free proteins (

EP and

EL) and the lowest-energy conformation of the bound complex (

EPL):

.

The K* algorithm approximates the binding constant of the algorithm

by including conformational entropy into the free energy calculation.

The K* algorithm considers only the lowest-energy conformations of the

free and bound complexes (denoted by the sets

P,

L, and

PL) to approximate the partition functions of each complex:

[14]

Design for specificity

The

design of protein–protein interactions must be highly specific because

proteins can interact with a large number of proteins; successful design

requires selective binders. Thus, protein design algorithms must be

able to distinguish between on-target (or

positive design) and off-target binding (or

negative design).

[2][38] One of the most prominent examples of design for specificity is the design of specific

bZIP-binding

peptides by Amy Keating and coworkers for 19 out of the 20 bZIP

families; 8 of these peptides were specific for their intended partner

over competing peptides.

[38][41][42] Further, positive and negative design was also used by Anderson and

coworkers to predict mutations in the active site of a drug target that

conferred resistance to a new drug; positive design was used to maintain

wild-type activity, while negative design was used to disrupt binding

of the drug.

[43] Recent computational redesign by Costas Maranas and coworkers was also capable of experimentally switching the

cofactor specificity of

Candida boidinii xylose reductase from

NADPH to

NADH.

[44]

Protein resurfacing

Protein

resurfacing consists of designing a protein's surface while preserving

the overall fold, core, and boundary regions of the protein intact.

Protein resurfacing is especially useful to alter the binding of a

protein to other proteins. One of the most important applications of

protein resurfacing was the design of the RSC3 probe to select broadly

neutralizing HIV antibodies at the NIH Vaccine Research Center. First,

residues outside of the binding interface between the gp120 HIV envelope

protein and the formerly discovered b12-antibody were selected to be

designed. Then, the sequence spaced was selected based on evolutionary

information, solubility, similarity with the wild-type, and other

considerations. Then the RosettaDesign software was used to find optimal

sequences in the selected sequence space. RSC3 was later used to

discover the broadly neutralizing antibody VRC01 in the serum of a

long-term HIV-infected non-progressor individual.

[45]

Design of globular proteins

Globular proteins

are proteins that contain a hydrophobic core and a hydrophilic surface.

Globular proteins often assume a stable structure, unlike

fibrous proteins,

which have multiple conformations. The three-dimensional structure of

globular proteins is typically easier to determine through

X-ray crystallography and

nuclear magnetic resonance than both fibrous proteins and

membrane proteins,

which makes globular proteins more attractive for protein design than

the other types of proteins. Most successful protein designs have

involved globular proteins. Both

RSD-1, and

Top7 were

de novo

designs of globular proteins. Five more protein structures were

designed, synthesized, and verified in 2012 by the Baker group. These

new proteins serve no biotic function, but the structures are intended

to act as building-blocks that can be expanded to incorporate functional

active sites. The structures were found computationally by using new

heuristics based on analyzing the connecting loops between parts of the

sequence that specify secondary structures.

[46]

Design of transmembrane proteins

Membrane

proteins are inherently hard to design, in large part because it is

hard to validate the designs experimentally for several reasons.

Membrane proteins are hard to purify. Their structure is hard to

characterize because they adopt their native conformation only in the

presence of a membrane. Crystallization is inherently hard, and NMR

studies of membrane proteins can fail because of their size.

Design of fibrous proteins

Fibrous proteins, such as

elastin or

collagen,

typically have no one structure. However, such proteins likely lack

random folds, and instead have folds defined within an ensemble of

structures. This ensemble defines their behavior. Thus, in theory it is

possible to rationally design fibrous proteins by selecting a sequence

that will populate a specific ensemble.

Other applications

One of the most desirable uses for protein design is for

biosensors,

proteins that will sense the presence of specific compounds. Some

attempts in the design of biosensors include sensors for unnatural

molecules including

TNT.

[47] More recently, Kuhlman and coworkers designed a biosensor of the

PAK1.

[48]

![\min E_{{T}}=\sum _{{i}}{\Big [}E_{i}(r_{i})+\sum _{{i\neq j}}E_{{ij}}(r_{i},r_{j}){\Big ]}\,](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3332d826843218136390cef20e4ee8e3694fc477)