War is a state of armed conflict between states, governments, societies and informal paramilitary groups, such as mercenaries, insurgents and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, aggression, destruction, and mortality, using regular or irregular military forces. Warfare refers to the common activities and characteristics of types of war, or of wars in general. Total war is warfare that is not restricted to purely legitimate military targets, and can result in massive civilian or other non-combatant suffering and casualties.

While some scholars see war as a universal and ancestral aspect of human nature,[2] others argue it is a result of specific socio-cultural or ecological circumstances.[3]

The deadliest war in history, in terms of the cumulative number of deaths since its start, is World War II, from 1939 to 1945, with 60–85 million deaths, followed by the Mongol conquests[4] at up to 60 million. As concerns a belligerent's losses in proportion to its prewar population, the most destructive war in modern history may have been the Paraguayan War (see Paraguayan War casualties). In 2013 war resulted in 31,000 deaths, down from 72,000 deaths in 1990.[5] In 2003, Richard Smalley identified war as the sixth biggest problem (out of ten) facing humanity for the next fifty years.[6] War usually results in significant deterioration of infrastructure and the ecosystem, a decrease in social spending, famine, large-scale emigration from the war zone, and often the mistreatment of prisoners of war or civilians.[7][8][9] For instance, of the nine million people who were on the territory of the Byelorussian SSR in 1941, some 1.6 million were killed by the Germans in actions away from battlefields, including about 700,000 prisoners of war, 500,000 Jews, and 320,000 people counted as partisans (the vast majority of whom were unarmed civilians).[10] Another byproduct of some wars is the prevalence of propaganda by some or all parties in the conflict,[11] and increased revenues by weapons manufacturers.[12]

Etymology

Mural of War (1896), by Gari Melchers

The English word war derives from the late Old English (circa.1050) words wyrre and werre, from Old French werre (also guerre as in modern French), in turn from the Frankish *werra, ultimately deriving from the Proto-Germanic *werzō 'mixture, confusion'. The word is related to the Old Saxon werran, Old High German werran, and the German verwirren, meaning “to confuse”, “to perplex”, and “to bring into confusion”.[13] In German, the equivalent is Krieg (from Proto-Germanic *krīganą 'to strive, be stubborn'); the Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian term for "war" is guerra, derived like the Old French term from the Germanic word.[14]

The scholarly study of war is sometimes called polemology (/ˌpɒləˈmɒlədʒi/ POL-ə-MOL-ə-jee), from the Greek polemos, meaning "war", and -logy, meaning "the study of".

Types

War must entail some degree of confrontation using weapons and other military technology and equipment by armed forces employing military tactics and operational art within a broad military strategy subject to military logistics. Studies of war by military theorists throughout military history have sought to identify the philosophy of war, and to reduce it to a military science. Modern military science considers several factors before a national defence policy is created to allow a war to commence: the environment in the area(s) of combat operations, the posture national forces will adopt on the commencement of a war, and the type of warfare troops will be engaged in.- Asymmetric warfare is a conflict between belligerents of drastically different levels of military capability and/or size.

- Biological warfare, or germ warfare, is the use of weaponized biological toxins or infectious agents such as bacteria, viruses, and fungi.

- Chemical warfare involves the use of weaponized chemicals in combat. Poison gas as a chemical weapon was principally used during World War I, and resulted in over a million estimated casualties, including more than 100,000 civilians.[15]

Ruins of Guernica (1937). The Spanish Civil War was one of Europe's bloodiest and most brutal civil wars.

- Civil war is a war between forces belonging to the same nation or political entity.

- Conventional warfare is declared war between states in which nuclear, biological, or chemical weapons are not used or see limited deployment.

- Cyberwarfare involves the actions by a nation-state or international organization to attack and attempt to damage another nation's information systems.

- Insurgency is a rebellion against authority, when those taking part in the rebellion are not recognized as belligerents (lawful combatants). An insurgency can be fought via counter-insurgency warfare, and may also be opposed by measures to protect the population, and by political and economic actions of various kinds aimed at undermining the insurgents' claims against the incumbent regime.

- Information warfare is the application of destructive force on a large scale against information assets and systems, against the computers and networks that support the four critical infrastructures (the power grid, communications, financial, and transportation).[16]

- Nuclear warfare is warfare in which nuclear weapons are the primary, or a major, method of achieving capitulation.

- Total war is warfare by any means possible, disregarding the laws of war, placing no limits on legitimate military targets, using weapons and tactics resulting in significant civilian casualties, or demanding a war effort requiring significant sacrifices by the friendly civilian population.

- Unconventional warfare, the opposite of conventional warfare, is an attempt to achieve military victory through acquiescence, capitulation, or clandestine support for one side of an existing conflict.

- War of aggression is a war for conquest or gain rather than self-defense; this can be the basis of war crimes under customary international law.

- War of liberation, Wars of national liberation or national liberation revolutions are conflicts fought by nations to gain independence. The term is used in conjunction with wars against foreign powers (or at least those perceived as foreign) to establish separate sovereign states for the rebelling nationality. From a different point of view, these wars are called insurgencies, rebellions, or wars of independence.

History

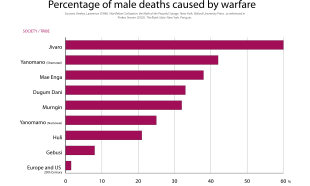

The

percentages of men killed in war in eight tribal societies, and Europe

and the U.S. in the 20th century. (Lawrence H. Keeley, archeologist)

The earliest recorded evidence of war belongs to the Mesolithic cemetery Site 117, which has been determined to be approximately 14,000 years old. About forty-five percent of the skeletons there displayed signs of violent death.[17] Since the rise of the state some 5,000 years ago,[18] military activity has occurred over much of the globe. The advent of gunpowder and the acceleration of technological advances led to modern warfare. According to Conway W. Henderson, "One source claims that 14,500 wars have taken place between 3500 BC and the late 20th century, costing 3.5 billion lives, leaving only 300 years of peace (Beer 1981: 20)."[19] An unfavorable review of this estimate[20] mentions the following regarding one of the proponents of this estimate: "In addition, perhaps feeling that the war casualties figure was improbably high, he changed "approximately 3,640,000,000 human beings have been killed by war or the diseases produced by war" to "approximately 1,240,000,000 human beings...&c."" The lower figure is more plausible,[21] but could also be on the high side, considering that the 100 deadliest acts of mass violence between 480 BCE and 2002 CE (wars and other man-made disasters with at least 300,000 and up to 66 million victims) claimed about 455 million human lives in total.[22] Primitive warfare is estimated to have accounted for 15.1 % of deaths and claimed 400 million victims.[23] Added to the aforementioned (and perhaps too high) figure of 1,240 million between 3500 BC and the late 20th century, this would mean a total of 1,640,000,000 people killed by war (including deaths from famine and disease caused by war) throughout the history and pre-history of mankind. For comparison, an estimated 1,680,000,000 people died from infectious diseases in the 20th century.[24] Nuclear warfare breaking out in August 1988, when nuclear arsenals were at peak level, and the aftermath thereof, could have reduced human population from 5,150,000,000 by 1,850,000,000 to 3,300,000,000 within a period of about one year, according to a projection that did not consider "the most severe predictions concerning nuclear winter".[25] This would have been a proportional reduction of the world’s population exceeding the reduction caused in the 14th century by the Black Death, and comparable in proportional terms with the plague’s impact on Europe's population in 1346–53.

In War Before Civilization, Lawrence H. Keeley, a professor at the University of Illinois, says approximately 90–95% of known societies throughout history engaged in at least occasional warfare,[26] and many fought constantly.[27]

Keeley describes several styles of primitive combat such as small raids, large raids, and massacres. All of these forms of warfare were used by primitive societies, a finding supported by other researchers.[28] Keeley explains that early war raids were not well organized, as the participants did not have any formal training. Scarcity of resources meant defensive works were not a cost effective way to protect the society against enemy raids.[29]

William Rubinstein wrote "Pre-literate societies, even those organised in a relatively advanced way, were renowned for their studied cruelty...'archaeology yields evidence of prehistoric massacres more severe than any recounted in ethnography [i.e., after the coming of the Europeans].'"

In Western Europe, since the late 18th century, more than 150 conflicts and about 600 battles have taken place.[31] During the 20th century, war resulted in a dramatic intensification of the pace of social changes, and was a crucial catalyst for the emergence of the Left as a force to be reckoned with.[32]

Recent rapid increases in the technologies of war, and therefore in its destructiveness (see mutual assured destruction), have caused widespread public concern, and have in all probability forestalled, and may altogether prevent the outbreak of a nuclear World War III. At the end of each of the last two World Wars, concerted and popular efforts were made to come to a greater understanding of the underlying dynamics of war and to thereby hopefully reduce or even eliminate it altogether. These efforts materialized in the forms of the League of Nations, and its successor, the United Nations.

According to the U.S. Bureau of the Census (1894), the Indian Wars of the 19th century cost the lives of about 50,000.[33]

In 1947, in view of the rapidly increasingly destructive consequences of modern warfare, and with a particular concern for the consequences and costs of the newly developed atom bomb, Albert Einstein famously stated, "I know not with what weapons World War III will be fought, but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones."[34]

Mao Zedong urged the socialist camp not to fear nuclear war with the United States since, even if "half of mankind died, the other half would remain while imperialism would be razed to the ground and the whole world would become socialist."[35]

The Human Security Report 2005 documented a significant decline in the number and severity of armed conflicts since the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s. However, the evidence examined in the 2008 edition of the Center for International Development and Conflict Management's "Peace and Conflict" study indicated the overall decline in conflicts had stalled.[36]

Largest by death toll

Three of the ten most costly wars, in terms of loss of life, have been waged in the last century. These are the two World Wars, followed by the Second Sino-Japanese War (which is sometimes considered part of World War II, or as overlapping). Most of the others involved China or neighboring peoples. The death toll of World War II, being over 60 million, surpasses all other war-death-tolls.| Deaths (millions) |

Date | War |

|---|---|---|

| 60.7–84.6 | 1939–1945 | World War II (see World War II casualties) |

| 60 | 13th century | Mongol Conquests (see Mongol invasions and Tatar invasions) |

| 40 | 1850–1864 | Taiping Rebellion (see Dungan revolt) |

| 39 | 1914–1918 | World War I (see World War I casualties) |

| 36 | 755–763 | An Shi Rebellion (death toll uncertain) |

| 25 | 1616–1662 | Qing dynasty conquest of Ming dynasty |

| 20 | 1937–1945 | Second Sino-Japanese War |

| 20 | 1370–1405 | Conquests of Tamerlane |

| 16 | 1862–1877 | Dungan revolt |

| 5–9 | 1917–1922 | Russian Civil War and Foreign Intervention |

Effects

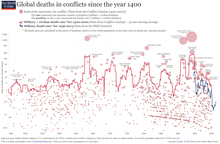

Global deaths in conflicts since the year 1400.[50]

Military and civilian casualties in recent human history

Human history had numerous wars coming and going, but the average number of people dying from war has fluctuated relatively little, being about 1 to 10 people dying per 100,000. However, major wars over shorter periods have resulted in much higher casualty rates, with 100-200 casualties per 100,000 over a few years. While conventional wisdom holds that casualties have increased in recent times due to technological improvements in warfare, this is not generally true. For instance, the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648) had about the same number of casualties per capita as World War I, although it was higher during World War II (WWII). That said, overall the number of casualties from war has not significantly increased in recent times. Quite to the contrary, on a global scale the time since WWII has been unusually peaceful.[52]

On military personnel

Military personnel subject to combat in war often suffer mental and physical injuries, including depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, disease, injury, and death.In every war in which American soldiers have fought in, the chances of becoming a psychiatric casualty – of being debilitated for some period of time as a consequence of the stresses of military life – were greater than the chances of being killed by enemy fire.During World War II, research conducted by US Army Brigadier General S.L.A. Marshall found, on average, 15% to 20% of American riflemen in WWII combat fired at the enemy.[53] In Civil War Collector’s Encyclopedia, F.A. Lord notes that of the 27,574 discarded muskets found on the Gettysburg battlefield, nearly 90% were loaded, with 12,000 loaded more than once and 6,000 loaded 3 to 10 times. These studies suggest most military personnel resist firing their weapons in combat, that – as some theorists argue – human beings have an inherent resistance to killing their fellow human beings.[53] Swank and Marchand’s WWII study found that after sixty days of continuous combat, 98% of all surviving military personnel will become psychiatric casualties. Psychiatric casualties manifest themselves in fatigue cases, confusional states, conversion hysteria, anxiety, obsessional and compulsive states, and character disorders.[53]

— No More Heroes, Richard Gabriel[31]

One-tenth of mobilised American men were hospitalised for mental disturbances between 1942 and 1945, and after thirty-five days of uninterrupted combat, 98% of them manifested psychiatric disturbances in varying degrees.

— 14–18: Understanding the Great War, Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau, Annette Becker[31]

The Apotheosis of War (1871) by Vasily Vereshchagin

Additionally, it has been estimated anywhere from 18% to 54% of Vietnam war veterans suffered from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.[53]

Based on 1860 census figures, 8% of all white American males aged 13 to 43 died in the American Civil War, including about 6% in the North and approximately 18% in the South.[54] The war remains the deadliest conflict in American history, resulting in the deaths of 620,000 military personnel. United States military casualties of war since 1775 have totaled over two million. Of the 60 million European military personnel who were mobilized in World War I, 8 million were killed, 7 million were permanently disabled, and 15 million were seriously injured.

The remains of dead Crow Indians killed and scalped by Sioux c. 1874

During Napoleon's retreat from Moscow, more French military personnel died of typhus than were killed by the Russians.[56] Of the 450,000 soldiers who crossed the Neman on 25 June 1812, less than 40,000 returned. More military personnel were killed from 1500–1914 by typhus than from military action.[57] In addition, if it were not for modern medical advances there would be thousands more dead from disease and infection. For instance, during the Seven Years' War, the Royal Navy reported it conscripted 184,899 sailors, of whom 133,708 died of disease or were 'missing'.[58]

It is estimated that between 1985 and 1994, 378,000 people per year died due to war.[59]

On civilians

Les Grandes Misères de la guerre depict the destruction unleashed on civilians during the Thirty Years' War.

Most wars have resulted in significant loss of life, along with destruction of infrastructure and resources (which may lead to famine, disease, and death in the civilian population). During the Thirty Years' War in Europe, the population of the Holy Roman Empire was reduced by 15 to 40 percent.[60][61] Civilians in war zones may also be subject to war atrocities such as genocide, while survivors may suffer the psychological aftereffects of witnessing the destruction of war.

Most estimates of World War II casualties indicate around 60 million people died, 40 million of which were civilians.[62] Deaths in the Soviet Union were around 27 million.[63] Since a high proportion of those killed were young men who had not yet fathered any children, population growth in the postwar Soviet Union was much lower than it otherwise would have been.[64]

On the economy

Once a war has ended, losing nations are sometimes required to pay war reparations to the victorious nations. In certain cases, land is ceded to the victorious nations. For example, the territory of Alsace-Lorraine has been traded between France and Germany on three different occasions.[citation needed]Typically, war becomes intertwined with the economy and many wars are partially or entirely based on economic reasons. Some economists[who?] believe war can stimulate a country's economy (high government spending for World War II is often credited with bringing the U.S. out of the Great Depression by most Keynesian economists) but in many cases, such as the wars of Louis XIV, the Franco-Prussian War, and World War I, warfare primarily results in damage the economy of the countries involved. For example, Russia's involvement in World War I took such a toll on the Russian economy that it almost collapsed and greatly contributed to the start of the Russian Revolution of 1917.[65]

World War II

Ruins of Warsaw's Napoleon Square in the aftermath of World War II

World War II was the most financially costly conflict in history; its belligerents cumulatively spent about a trillion U.S. dollars on the war effort (as adjusted to 1940 prices).[66][67] The Great Depression of the 1930s ended as nations increased their production of war materials.[68]

By the end of the war, 70% of European industrial infrastructure was destroyed.[69] Property damage in the Soviet Union inflicted by the Axis invasion was estimated at a value of 679 billion rubles. The combined damage consisted of complete or partial destruction of 1,710 cities and towns, 70,000 villages/hamlets, 2,508 church buildings, 31,850 industrial establishments, 40,000 mi (64,374 km) of railroad, 4100 railroad stations, 40,000 hospitals, 84,000 schools, and 43,000 public libraries.[70]

On the arts

War leads to forced migration causing potentially large displacements of population. Among forced migrants there are usually relatively large shares of artists and other types of creative people, causing so the war effects to be particularly harmful for the country’s creative potential in the long-run.[71] War also has a negative effect on an artists’ individual life-cycle output.[72]In war, cultural institutions, such as libraries, can become "targets in themselves; their elimination was a way to denigrate and demoralize the enemy population." The impact such destruction can have on a society is important because "in an era in which competing ideologies fuel internal and international conflict, the destruction of libraries and other items of cultural significance is neither random nor irrelevant. Preserving the world’s repositories of knowledge is crucial to ensuring that the darkest moments of history do not endlessly repeat themselves."[73]

Aims

Entities deliberately contemplating going to war and entities considering whether to end a war may formulate war aims as an evaluation/propaganda tool. War aims may stand as a proxy for national-military resolve.[74]Definition

Fried defines war aims as "the desired territorial, economic, military or other benefits expected following successful conclusion of a war".[75]Classification

Tangible/intangible aims:- Tangible war aims may involve (for example) the acquisition of territory (as in the German goal of Lebensraum in the first half of the 20th century) or the recognition of economic concessions (as in the Anglo-Dutch Wars).

- Intangible war aims – like the accumulation of credibility or reputation[76] – may have more tangible expression ("conquest restores prestige, annexation increases power").[77]

- Explicit war aims may involve published policy decisions.

- Implicit war aims[78] can take the form of minutes of discussion, memoranda and instructions.[79]

- "Positive war aims" cover tangible outcomes.

- "Negative war aims" forestall or prevent undesired outcomes.[80]

Ongoing conflicts

There are currently dozens of ongoing armed conflicts around the world, the deadliest of which is the Syrian Civil War.Limiting and stopping

Anti-war rally in Washington, D.C., March 15, 2003

Religious groups have long formally opposed or sought to limit war as in the Second Vatican Council document Gaudiem et Spes: "Any act of war aimed indiscriminately at the destruction of entire cities of extensive areas along with their population is a crime against God and man himself. It merits unequivocal and unhesitating condemnation."[82]

Anti-war movements have existed for every major war in the 20th century, including, most prominently, World War I, World War II, and the Vietnam War. In the 21st century, worldwide anti-war movements occurred in response to the United States invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq. Protests opposing the War in Afghanistan occurred in Europe, Asia, and the United States. Organizations like Stop the War Coalition, based in the United Kingdom, worked on campaigning against the war.[83]

The Mexican Drug War, with estimated casualties of 40,000 since December 2006, has recently faced fundamental opposition.[84] In 2011, the movement for peace and justice has started a popular middle-class movement against the war. It won the recognition of President Calderon, who began war.[85]

Theories for motivation

The Ottoman campaign for territorial expansion in Europe in 1566

There is no scholarly agreement on which are the most common motivations for war.[86] Carl von Clausewitz said, 'Every age had its own kind of war, its own limiting conditions, and its own peculiar preconceptions.'[87]

Psychoanalytic psychology

Dutch psychoanalyst Joost Meerloo held that, "War is often...a mass discharge of accumulated internal rage (where)...the inner fears of mankind are discharged in mass destruction."[88] Thus war can sometimes be a means by which man's own frustration at his inability to master his own self is expressed and temporarily relieved via his unleashing of destructive behavior upon others. In this destructive scenario, these others are made to serve as the scapegoat of unspoken and subconscious frustrations and fears.Other psychoanalysts such as E.F.M. Durban and John Bowlby have argued human beings are inherently violent.[89] This aggressiveness is fueled by displacement and projection where a person transfers his or her grievances into bias and hatred against other races, religions, nations or ideologies. By this theory, the nation state preserves order in the local society while creating an outlet for aggression through warfare.

The Italian psychoanalyst Franco Fornari, a follower of Melanie Klein, thought war was the paranoid or projective “elaboration” of mourning.[90] Fornari thought war and violence develop out of our “love need”: our wish to preserve and defend the sacred object to which we are attached, namely our early mother and our fusion with her. For the adult, nations are the sacred objects that generate warfare. Fornari focused upon sacrifice as the essence of war: the astonishing willingness of human beings to die for their country, to give over their bodies to their nation.

Despite Fornari's theory that man's altruistic desire for self-sacrifice for a noble cause is a contributing factor towards war,few wars have originated from a desire for war among the general populace.[91] Far more often the general population has been reluctantly drawn into war by its rulers. One psychological theory that looks at the leaders is advanced by Maurice Walsh.[92] He argues the general populace is more neutral towards war and wars occur when leaders with a psychologically abnormal disregard for human life are placed into power. War is caused by leaders who seek war such as Napoleon and Hitler. Such leaders most often come to power in times of crisis when the populace opts for a decisive leader, who then leads the nation to war.

Naturally, the common people don't want war; neither in Russia nor in England nor in America, nor for that matter in Germany. That is understood. But, after all, it is the leaders of the country who determine the policy and it is always a simple matter to drag the people along, whether it is a democracy or a fascist dictatorship or a Parliament or a Communist dictatorship. ... the people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders. That is easy. All you have to do is tell them they are being attacked and denounce the pacifists for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same way in any country.

— Hermann Göring at the Nuremberg trials, April 18, 1946[93]

Evolutionary

Women and priests retrieve the dead bodies of Swabian soldiers just outside the city gates of Constance after the battle of Schwaderloh. (Luzerner Schilling)

Several theories concern the evolutionary origins of warfare. There are two main schools: One sees organized warfare as emerging in or after the Mesolithic as a result of complex social organization and greater population density and competition over resources; the other sees human warfare as a more ancient practice derived from common animal tendencies, such as territoriality and sexual competition.[94]

The latter school argues that since warlike behavior patterns are found in many primate species such as chimpanzees,[95] as well as in many ant species,[96] group conflict may be a general feature of animal social behavior. Some proponents of the idea argue that war, while innate, has been intensified greatly by developments of technology and social organization such as weaponry and states.[97]

Psychologist and linguist Steven Pinker argued that war-related behaviors may have been naturally selected in the ancestral environment due to the benefits of victory. He also argued that in order to have credible deterrence against other groups (as well as on an individual level), it was important to have a reputation for retaliation, causing humans to develop instincts for revenge as well as for protecting a group's (or an individual's) reputation ("honor").

Increasing population and constant warfare among the Maya city-states over resources may have contributed to the eventual collapse of the Maya civilization by AD 900.

Crofoot and Wrangham have argued that warfare, if defined as group interactions in which "coalitions attempt to aggressively dominate or kill members of other groups", is a characteristic of most human societies. Those in which it has been lacking "tend to be societies that were politically dominated by their neighbors".[99]

Ashley Montagu strongly denied universalistic instinctual arguments, arguing that social factors and childhood socialization are important in determining the nature and presence of warfare. Thus, he argues, warfare is not a universal human occurrence and appears to have been a historical invention, associated with certain types of human societies.[100] Montagu's argument is supported by ethnographic research conducted in societies where the concept of aggression seems to be entirely absent, e.g. the Chewong and Semai of the Malay peninsula.[101] Bobbi S. Low has observed correlation between warfare and education, noting societies where warfare is commonplace encourage their children to be more aggressive.[102]

Agner Fog finds that non-modern social groups are either warlike or peaceful, depending on the environment. War is common where neighbor groups depend on the same resources, where food and other important resources are concentrated in defendable patches (contest competition), and where traveling to enemy territory is easy. Peaceful groups are found where war is prevented by geographical barriers, where food sources are sparse and not defendable (scramble competition), and where a group has specialized into a unique ecological niche that other groups are unable to penetrate. These living conditions affect the psychology of the populations in such a way that warlike groups develop a hierarchical and authoritarian social organization (called regal), while the peaceful groups develop egalitarian social structures and a tolerant culture (called kungic).[103]

Economic

War can be seen as a growth of economic competition in a competitive international system. In this view wars begin as a pursuit of markets for natural resources and for wealth. War has also been linked to economic development by economic historians and development economists studying state-building and fiscal capacity.[104] While this theory has been applied to many conflicts, such counter arguments become less valid as the increasing mobility of capital and information level the distributions of wealth worldwide, or when considering that it is relative, not absolute, wealth differences that may fuel wars. There are those on the extreme right of the political spectrum who provide support, fascists in particular, by asserting a natural right of a strong nation to whatever the weak cannot hold by force.[105][106] Some centrist, capitalist, world leaders, including Presidents of the United States and U.S. Generals, expressed support for an economic view of war.

Marxist

The Marxist theory of war is quasi-economic in that it states all modern wars are caused by competition for resources and markets between great (imperialist) powers, claiming these wars are a natural result of the free market and class system. Part of the theory is that war will disappear once a world revolution, over-throwing free markets and class systems, has occurred. Marxist philosopher Rosa Luxemburg theorized that imperialism was the result of capitalist countries needing new markets. Expansion of the means of production is only possible if there is a corresponding growth in consumer demand. Since the workers in a capitalist economy would be unable to fill the demand, producers must expand into non-capitalist markets to find consumers for their goods, hence driving imperialism.[107]Demographic

Demographic theories can be grouped into two classes, Malthusian and youth bulge theories:Malthusian

U.S. Marine helicopter on patrol in Somalia as part of the Unified Task Force, 1992

Malthusian theories see expanding population and scarce resources as a source of violent conflict.

Pope Urban II in 1095, on the eve of the First Crusade, spoke:

For this land which you now inhabit, shut in on all sides by the sea and the mountain peaks, is too narrow for your large population; it scarcely furnishes food enough for its cultivators. Hence it is that you murder and devour one another, that you wage wars, and that many among you perish in civil strife. Let hatred, therefore, depart from among you; let your quarrels end. Enter upon the road to the Holy Sepulchre; wrest that land from a wicked race, and subject it to yourselves.[108]This is one of the earliest expressions of what has come to be called the Malthusian theory of war, in which wars are caused by expanding populations and limited resources. Thomas Malthus (1766–1834) wrote that populations always increase until they are limited by war, disease, or famine.[109]

Youth bulge

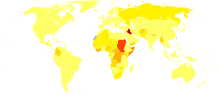

Median age by country. War reduces life expectancy. A youth bulge is evident for Africa, and to a lesser extent in some countries in West Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia and Central America.

According to Heinsohn, who proposed youth bulge theory in its most generalized form, a youth bulge occurs when 30 to 40 percent of the males of a nation belong to the "fighting age" cohorts from 15 to 29 years of age. It will follow periods with total fertility rates as high as 4–8 children per woman with a 15–29-year delay.

Heinsohn saw both past "Christianist" European colonialism and imperialism, as well as today's Islamist civil unrest and terrorism as results of high birth rates producing youth bulges.[112] Among prominent historical events that have been attributed to youth bulges are the role played by the historically large youth cohorts in the rebellion and revolution waves of early modern Europe, including the French Revolution of 1789,[113] and the effect of economic depression upon the largest German youth cohorts ever in explaining the rise of Nazism in Germany in the 1930s.[114] The 1994 Rwandan Genocide has also been analyzed as following a massive youth bulge.[115]

Youth bulge theory has been subjected to statistical analysis by the World Bank,[116] Population Action International,[117] and the Berlin Institute for Population and Development.[118] Youth bulge theories have been criticized as leading to racial, gender and age discrimination.[119]

Rationalist

U.S. soldiers directing artillery on enemy trucks in A Shau Valley, April 1968

Rationalism is an international relations theory or framework. Rationalism (and Neorealism (international relations)) operate under the assumption that states or international actors are rational, seek the best possible outcomes for themselves, and desire to avoid the costs of war.[120] Under a game theory approach, rationalist theories posit all actors can bargain, would be better off if war did not occur, and likewise seek to understand why war nonetheless reoccurs. In "Rationalist Explanations for War", James Fearon examined three rationalist explanations for why some countries engage in war:

- Issue indivisibilities

- Incentives to misrepresent or information asymmetry

- Commitment problems[120]

U.S. Marines direct a concentration of fire at the enemy, Vietnam, 8 May 1968

"Information asymmetry with incentives to misrepresent" occurs when two countries have secrets about their individual capabilities, and do not agree on either: who would win a war between them, or the magnitude of state's victory or loss. For instance, Geoffrey Blainey argues that war is a result of miscalculation of strength. He cites historical examples of war and demonstrates, "war is usually the outcome of a diplomatic crisis which cannot be solved because both sides have conflicting estimates of their bargaining power."[121] Thirdly, bargaining may fail due to the states' inability to make credible commitments.[122]

Within the rationalist tradition, some theorists have suggested that individuals engaged in war suffer a normal level of cognitive bias,[123] but are still "as rational as you and me".[124] According to philosopher Iain King, "Most instigators of conflict overrate their chances of success, while most participants underrate their chances of injury...."[125] King asserts that "Most catastrophic military decisions are rooted in GroupThink" which is faulty, but still rational.[126]

The rationalist theory focused around bargaining is currently under debate. The Iraq War proved to be an anomaly that undercuts the validity of applying rationalist theory to some wars.[127]

Political science

The statistical analysis of war was pioneered by Lewis Fry Richardson following World War I. More recent databases of wars and armed conflict have been assembled by the Correlates of War Project, Peter Brecke and the Uppsala Conflict Data Program.[citation needed]The following subsections consider causes of war from system, societal, and individual levels of analysis. This kind of division was first proposed by Kenneth Waltz in Man, the State, and War and has been often used by political scientists since then.[128]:143

System-level theories

There are several different international relations theory schools. Supporters of realism in international relations argue that the motivation of states is the quest for security, and conflicts can arise from the inability to distinguish defense from offense, which is called the security dilemma.[128]:145Within the realist school as represented by scholars such as Henry Kissinger and Hans Morgenthau, and the neorealist school represented by scholars such as Kenneth Waltz and John Mearsheimer, two main sub-theories are:

- Balance of power theory: States have the goal of preventing a single state from becoming a hegemon, and war is the result of the would-be hegemon's persistent attempts at power acquisition. In this view, an international system with more equal distribution of power is more stable, and "movements toward unipolarity are destabilizing."[128]:147 However, evidence has shown power polarity is not actually a major factor in the occurrence of wars.[128]:147–48

- Power transition theory: Hegemons impose stabilizing conditions on the world order, but they eventually decline, and war occurs when a declining hegemon is challenged by another rising power or aims to preemptively suppress them.[128]:148 On this view, unlike for balance-of-power theory, wars become more probable when power is more equally distributed. This "power preponderance" hypothesis has empirical support.[128]:148

Liberalism as it relates to international relations emphasizes factors such as trade, and its role in disincentivizing conflict which will damage economic relations. Realists[who?] respond that military force may sometimes be at least as effective as trade at achieving economic benefits, especially historically if not as much today.[128]:149 Furthermore, trade relations which result in a high level of dependency may escalate tensions and lead to conflict.[128]:150 Empirical data on the relationship of trade to peace are mixed, and moreover, some evidence suggests countries at war don't necessarily trade less with each other.[128]:150

Societal-level theories

- Diversionary theory, also known as the "scapegoat hypothesis", suggests the politically powerful may use war to as a diversion or to rally domestic popular support.[128]:152 This is supported by literature showing out-group hostility enhances in-group bonding, and a significant domestic "rally effect" has been demonstrated when conflicts begin.[128]:152–13 However, studies examining the increased use of force as a function of need for internal political support are more mixed.[128]:152–53 U.S. war-time presidential popularity surveys taken during the presidencies of several recent U.S. leaders have supported diversionary theory.[129]

Individual-level theories

These theories suggest differences in people's personalities, decision-making, emotions, belief systems, and biases are important in determining whether conflicts get out of hand.[128]:157 For instance, it has been proposed that conflict is modulated by bounded rationality and various cognitive biases,[128]:157 such as prospect theory.[130]Ethics

Morning after the Battle of Waterloo, by John Heaviside Clark, 1816

The morality of war has been the subject of debate for thousands of years.[131]

The two principal aspects of ethics in war, according to the just war theory, are jus ad bellum and Jus in bello.[132]

Jus ad bellum (right to war), dictates which unfriendly acts and circumstances justify a proper authority in declaring war on another nation. There are six main criteria for the declaration of a just war: first, any just war must be declared by a lawful authority; second, it must be a just and righteous cause, with sufficient gravity to merit large-scale violence; third, the just belligerent must have rightful intentions – namely, that they seek to advance good and curtail evil; fourth, a just belligerent must have a reasonable chance of success; fifth, the war must be a last resort; and sixth, the ends being sought must be proportional to means being used.[133][134]

Jus in bello (right in war), is the set of ethical rules when conducting war. The two main principles are proportionality and discrimination. Proportionality regards how much force is necessary and morally appropriate to the ends being sought and the injustice suffered.[135] The principle of discrimination determines who are the legitimate targets in a war, and specifically makes a separation between combatants, who it is permissible to kill, and non-combatants, who it is not.[135] Failure to follow these rules can result in the loss of legitimacy for the just-war-belligerent.

In besieged Leningrad.

"Hitler ordered that Moscow and Leningrad were to be razed to the

ground; their inhabitants were to be annihilated or driven out by

starvation. These intentions were part of the 'General Plan East'." – The Oxford Companion to World War II.[137]

The just war theory was foundational in the creation of the United Nations and in International Law's regulations on legitimate war.[131]

Fascism, and the ideals it encompasses, such as Pragmatism, racism, and social Darwinism, hold that violence is good.[138][139] Pragmatism holds that war and violence can be good if it serves the ends of the people, without regard for universal morality. Racism holds that violence is good so that a master race can be established, or to purge an inferior race from the earth, or both. Social Darwinism asserts that violence is sometimes necessary to weed the unfit from society so civilization can flourish. These are broad archetypes for the general position that the ends justify the means. Lewis Coser, U.S. conflict theorist and sociologist, argued conflict provides a function and a process whereby a succession of new equilibriums are created. Thus, the struggle of opposing forces, rather than being disruptive, may be a means of balancing and maintaining a social structure or society.