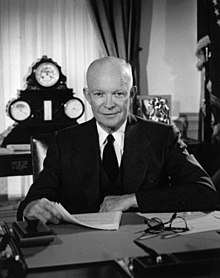

President Dwight D. Eisenhower famously warned U.S. citizens about the "military–industrial complex" in his farewell address.

The military–industrial complex (MIC) is an informal alliance between a nation's military and the defense industry which supplies it, seen together as a vested interest which influences public policy. A driving factor behind this relationship between the government and defense-minded corporations is that both sides benefit—one side from obtaining war weapons, and the other from being paid to supply them. The term is most often used in reference to the system behind the military of the United States, where it is most prevalent and gained popularity after its use in the farewell address of President Dwight D. Eisenhower on January 17, 1961. In 2011, the United States spent more (in absolute numbers) on its military than the next 13 nations combined.

In a U.S. context, the appellation given to it sometimes is extended to military–industrial–congressional complex (MICC), adding the U.S. Congress to form a three-sided relationship termed an iron triangle.[10] These relationships include political contributions, political approval for military spending, lobbying to support bureaucracies, and oversight of the industry; or more broadly to include the entire network of contracts and flows of money and resources among individuals as well as corporations and institutions of the defense contractors, private military contractors, The Pentagon, the Congress and executive branch.[11]

A similar thesis was originally expressed by Daniel Guérin, in his 1936 book Fascism and Big Business, about the fascist government support to heavy industry. It can be defined as, "an informal and changing coalition of groups with vested psychological, moral, and material interests in the continuous development and maintenance of high levels of weaponry, in preservation of colonial markets and in military-strategic conceptions of internal affairs."[12] An exhibit of the trend was made in Franz Leopold Neumann's book Behemoth: The Structure and Practice of National Socialism in 1942, a study of how Nazism came into a position of power in a democratic state.

Such type of complex, in the First World War had taken US to the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917.[vague]

Etymology

Eisenhower's farewell address, January 17, 1961. The term military–industrial complex is used at 8:16. Length: 15:30.

President of the United States (and five-star general during World War II) Dwight D. Eisenhower used the term in his Farewell Address to the Nation on January 17, 1961:

A vital element in keeping the peace is our military establishment. Our arms must be mighty, ready for instant action, so that no potential aggressor may be tempted to risk his own destruction...The phrase was thought to have been "war-based" industrial complex before becoming "military" in later drafts of Eisenhower's speech, a claim passed on only by oral history.[13] Geoffrey Perret, in his biography of Eisenhower, claims that, in one draft of the speech, the phrase was "military–industrial–congressional complex", indicating the essential role that the United States Congress plays in the propagation of the military industry, but the word "congressional" was dropped from the final version to appease the then-currently elected officials.[14] James Ledbetter calls this a "stubborn misconception" not supported by any evidence; likewise a claim by Douglas Brinkley that it was originally "military–industrial–scientific complex".[14][15] Additionally, Henry Giroux claims that it was originally "military–industrial–academic complex".[16] The actual authors of the speech were Eisenhower's speechwriters Ralph E. Williams and Malcolm Moos.[17]

This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence—economic, political, even spiritual—is felt in every city, every statehouse, every office of the federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society. In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military–industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists, and will persist. We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals so that security and liberty may prosper together. [emphasis added]

Attempts to conceptualize something similar to a modern "military–industrial complex" existed before Eisenhower's address. Ledbetter finds the precise term used in 1947 in close to its later meaning in an article in Foreign Affairs by Winfield W. Riefler.[14][18] In 1956, sociologist C. Wright Mills had claimed in his book The Power Elite that a class of military, business, and political leaders, driven by mutual interests, were the real leaders of the state, and were effectively beyond democratic control. Friedrich Hayek mentions in his 1944 book The Road to Serfdom the danger of a support of monopolistic organization of industry from World War II political remnants:

Another element which after this war is likely to strengthen the tendencies in this direction will be some of the men who during the war have tasted the powers of coercive control and will find it difficult to reconcile themselves with the humbler roles they will then have to play [in peaceful times]."[19]Vietnam War–era activists, such as Seymour Melman, referred frequently to the concept, and use continued throughout the Cold War: George F. Kennan wrote in his preface to Norman Cousins's 1987 book The Pathology of Power, "Were the Soviet Union to sink tomorrow under the waters of the ocean, the American military–industrial complex would have to remain, substantially unchanged, until some other adversary could be invented. Anything else would be an unacceptable shock to the American economy."[20]

U.S. military presence around the world in 2007. As of 2018, the U.S. still had many bases and troops stationed globally.

In the late 1990s James Kurth asserted, "By the mid-1980s ... the term had largely fallen out of public discussion." He went on to argue that "[w]hatever the power of arguments about the influence of the military–industrial complex on weapons procurement during the Cold War, they are much less relevant to the current era".[21]

Contemporary students and critics of American militarism continue to refer to and employ the term, however. For example, historian Chalmers Johnson uses words from the second, third, and fourth paragraphs quoted above from Eisenhower's address as an epigraph to Chapter Two ("The Roots of American Militarism") of a recent volume[22] on this subject. P. W. Singer's book concerning private military companies illustrates contemporary ways in which industry, particularly an information-based one, still interacts with the U.S. federal and the Pentagon.[23]

The expressions permanent war economy and war corporatism are related concepts that have also been used in association with this term. The term is also used to describe comparable collusion in other political entities such as the German Empire (prior to and through the first world war), Britain, France, and (post-Soviet) Russia.[citation needed]

Linguist and anarchist theorist Noam Chomsky has suggested that "military–industrial complex" is a misnomer because (as he considers it) the phenomenon in question "is not specifically military."[24] He asserts, "There is no military–industrial complex: it's just the industrial system operating under one or another pretext (defense was a pretext for a long time)."[25]

Post-Cold War

U.S. Defense Spending 2001–2017

United States defense contractors bewailed what they called declining government weapons spending at the end of the Cold War.[26][27] They saw escalation of tensions, such as with Russia over Ukraine, as new opportunities for increased weapons sales, and have pushed the political system, both directly and through industry lobby groups such as the National Defense Industrial Association, to spend more on military hardware. Pentagon contractor-funded American think tanks such as the Lexington Institute and the Atlantic Council have also demanded increased spending in view of the perceived Russian threat.[27][28] Independent Western observers such as William Hartung, director of the Arms & Security Project at the Center for International Policy, noted that "Russian saber-rattling has additional benefits for weapons makers because it has become a standard part of the argument for higher Pentagon spending—even though the Pentagon already has more than enough money to address any actual threat to the United States."[27][29]

Current applications

According to SIPRI, total world spending on military expenses in 2009 was $1.531 trillion U.S. dollars. 46.5% of this total, roughly $712 billion U.S. dollars, was spent by the United States.[31] The privatization of the production and invention of military technology also leads to a complicated relationship with significant research and development of many technologies. The military budget of the United States for the 2009 fiscal year was $515.4 billion. Adding emergency discretionary spending and supplemental spending, brings the sum to $651.2 billion.[32] This does not include many military-related items that are outside of the Defense Department budget. Overall the U.S. federal government is spending about $1 trillion annually on defense-related purposes.[33]

In a 2012 story, Salon reported, "Despite a decline in global arms sales in 2010 due to recessionary pressures, the U.S. increased its market share, accounting for a whopping 53 percent of the trade that year. Last year saw the U.S. on pace to deliver more than $46 billion in foreign arms sales."[34] The defense industry also tends to contribute heavily to incumbent members of Congress.[35]

The concept of a military–industrial complex has been expanded to include the entertainment and creative[36] industries. For an example in practice, Matthew Brummer describes Japan's Manga Military and how the Ministry of Defense uses popular culture and the moe that it engenders to shape domestic and international perceptions.