Nativism is the political policy of promoting the interests of native inhabitants against those of immigrants, including by supporting immigration-restriction measures.

In scholarly studies nativism is a standard technical

term. Those who hold this political view, however, do not typically

accept the label. Dindar (2009) wrote, "nativists... do not consider

themselves as nativists. For them it is a negative term and they rather

consider themselves as 'Patriots'".

Arguments for immigration restriction

Immigration restrictionist sentiment is typically justified with one or more of the following arguments and claims about immigrants:

- Government expense: Government expenses may exceed tax revenue relating to new immigrants;

- Language: Isolate themselves in their own communities and refuse to learn the local language;

- Employment: Acquire jobs that would have otherwise been available to native citizens, depressing native employment; create an oversupply of labor, depressing wages;

- Patriotism: Damage a sense of community and nationality;

- Environment: Increase the consumption of scarce resources; their move from low- to high-pollution economies increases pollution;

- Welfare: Make heavy use of social welfare systems;

- Overpopulation: May overpopulate countries;

- Culture: Can swamp a native population and replace its culture with their own;

- Housing: Increase in housing costs: migrant families can reduce vacancies and cause rent increases.

By country

Australia

Many Australians opposed the influx of Chinese immigrants at time of the nineteenth-century gold rushes. When the separate Australian colonies formed the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901, the new nation adopted "White Australia" as one of its founding principles. Under the White Australia policy, entry of Chinese and other Asians remained controversial until well after World War II, although the country remained home to many long-established Chinese families dating from before the adoption of White Australia. By contrast, most Pacific Islanders were deported soon after the policy was adopted, while the remainder were forced out of the canefields where they had worked for decades.Hostility of native-born white Australians toward British and Irish immigrants in the late 19th century was manifested in a new party, the Australian Natives' Association.

Since early 2000, opposition has mounted to asylum seekers arriving in boats from Indonesia.

Brazil

The Brazilian elite desired the racial whitening of the country, similarly to Argentina and Uruguay. The country encouraged European immigration, but non-white immigration always faced considerable backlash. On July 28, 1921, representatives Andrade Bezerra and Cincinato Braga proposed a law whose Article 1 provided: "The immigration of individuals from the black race to Brazil is prohibited." On October 22, 1923, representative Fidélis Reis produced another bill on the entry of immigrants, whose fifth article was as follows: "The entry of settlers from the black race into Brazil is prohibited. For Asian [immigrants] there will be allowed each year a number equal to 5% of those residing in the country.(...)".In the 19th and 20th centuries, there were negative feelings toward the communities of German, Italian, Japanese, and Jewish immigrants, who conserved their language and culture instead of adopting Portuguese and Brazilian habit (so that nowadays Brazil has the biggest communities in the Americas of speakers of German and Venetian), were seen as particularly tendentious to form ghettos, had high rates of endogamy (in Brazil, it is regarded as usual for people of different backgrounds to miscegenate), among other concerns.

It affected more harshly the Japanese, because they were Asian, and thus seen as an obstacle of the whitening of Brazil. Oliveira Viana, a Brazilian jurist, historian and sociologist described the Japanese immigrants as follows: "They (Japanese) are like sulfur: insoluble". The Brazilian magazine "O Malho" in its edition of December 5, 1908 issued a charge of Japanese immigrants with the following legend: "The government of São Paulo is stubborn. After the failure of the first Japanese immigration, it contracted 3,000 yellow people. It insists on giving Brazil a race diametrically opposite to ours". In 1941, the Brazilian Minister of Justice, Francisco Campos, defended the ban on admission of 400 Japanese immigrants in São Paulo and wrote: "their despicable standard of living is a brutal competition with the country's worker; their selfishness, their bad faith, their refractory character, make them a huge ethnic and cultural cyst located in the richest regions of Brazil".

Some years before World War II, the government of President Getúlio Vargas initiated a process of forced assimilation of people of immigrant origin in Brazil. The Constitution of 1934 had a legal provision about the subject: "The concentration of immigrants anywhere in the country is prohibited; the law should govern the selection, location and assimilation of the alien". The assimilationist project affected mainly German, Italian, Japanese and Jewish immigrants and their descendants.

During World War II they were seen as more loyal to their countries of origin than to Brazil. In fact, there were violent revolts in the Japanese community of the states of São Paulo and Paraná when Emperor Hirohito declared that Japan surrendered and he was not a deity, which was thought as a conspiracy trying to hurt Japanese honor and strength. Nevertheless, it followed hostility from the government. The Japanese Brazilian community was strongly marked by restrictive measures when Brazil declared war against Japan in August 1942. Japanese Brazilians could not travel the country without safe conduct issued by the police; over 200 Japanese schools were closed and radio equipment was seized to prevent transmissions on short wave from Japan. The goods of Japanese companies were confiscated and several companies of Japanese origin had interventions, including the newly founded Banco América do Sul. Japanese Brazilians were prohibited from driving motor vehicles (even if they were taxi drivers), buses or trucks on their property. The drivers employed by Japanese had to have permission from the police. Thousands of Japanese immigrants were arrested or expelled from Brazil on suspicion of espionage. There were many anonymous denunciations because of "activities against national security" arising from disagreements between neighbours, recovery of debts and even fights between children. Japanese Brazilians were arrested for "suspicious activity" when they were in artistic meetings or picnics. On July 10, 1943, approximately 10,000 Japanese and German immigrants who lived in Santos had 24 hours to close their homes and businesses and move away from the Brazilian coast. The police acted without any notice. About 90% of people displaced were Japanese. To reside in Baixada Santista, the Japanese had to have a safe conduct. In 1942, the Japanese community who introduced the cultivation of pepper in Tomé-Açu, in Pará, was virtually turned into a "concentration camp" (expression of the time) from which no Japanese could leave. This time, the Brazilian ambassador in Washington, D.C., Carlos Martins Pereira e Sousa, encouraged the government of Brazil to transfer all the Japanese Brazilians to "internment camps" without the need for legal support, in the same manner as was done with the Japanese residents in the United States. No single suspicion of activities of Japanese against "national security" was confirmed.

Nowadays, nativism in Brazil affects primarily migrants from elsewhere in the Third World, such as the new wave of Levantine Arabs (this time, mostly Muslim from Palestine instead of overwhelmingly Christian from Syria and Lebanon), South and East Asians (primarily Mainland Chinese), Spanish-speakers and Amerindians from neighboring South American countries and, especially, West Africans and Haitians. Following the 2010 Haiti earthquake and considerable illegal immigration to northern Brazil and São Paulo, a subsequent debate in the population was concerned with the reasons why Brazil has such lax laws and enforcement concerning illegal immigration.

According to the 1988's Brazilian Constitution, it is an unbailable crime to address someone in an offensive racist way, and it is illegal to discriminate someone on the basis of his or her race, skin color, national or regional origin or nationality (for more, see anti-discrimination laws in Brazil), thus nativism and opposition to multiculturalism would be too much of a polemic and delicate topic to be openly discussed as a basic ideology of even the most right-leaning modern political parties.

Canada

Nativism was common in Canada (though the term originated in the U.S.). It took several forms. Hostility to the Chinese and other Asians was intense, and involved provincial laws that hindered immigration of Chinese and Japanese and blocked their economic mobility. In 1942 Japanese Canadians were forced into detention camps in response to Japanese aggression in World War II.Throughout the 19th century, well into the 20th, the Orange Order in Canada attacked and tried to politically defeat the Irish Catholics. The Ku Klux Klan spread in the mid-1920s from the U.S. to parts of Canada, especially Saskatchewan, where it helped topple the Liberal government. The Klan creed was, historian Martin Robin argues, in the mainstream of Protestant Canadian sentiment, for it was based on "Protestantism, separation of Church and State, pure patriotism, restrictive and selective immigration, one national public school, one flag and one language—English."

In World War I, Canadian naturalized citizens of German or Austrian origins were stripped of their right to vote, and tens of thousands of Ukrainians (who were born in the Austro-Hungarian Empire) were rounded up and put in internment camps.

Hostility of native-born Canadians to competition from English immigrants in the early 20th century was expressed in signs that read, "No English Need Apply!" The resentment came because the immigrants identified more with England than with Canada.

In the British Empire, traditions of anti-Catholicism in Britain led to fears that Catholics were a threat to the national (British) values. In Canada, the Orange Order (of Irish Protestants) campaigned vigorously against the Catholics throughout the 19th century, often with violent confrontations. Both sides were immigrants from Ireland and neither side claimed loyalty to Canada. The Orange Order was much less influential in the U.S., especially after a major riot in New York City in 1871.

Hong Kong

Nativism in Hong Kong is often used as a synonymy with localism, which strives for the autonomy of Hong Kong and resist China's authorities influence in the city. In addition to their strong anti-communist and pro-democracy tendency, It often holds a strong anti-mainland sentiments, especially the influx of the mainland tourists and immigrants, seeing them as a threat to Hong Kong identity and culture.European countries

For the Poles in the mining districts of western Germany before 1914, it was nationalism (on both the German and the Polish sides), which kept Polish workers, who had established an associational structure approaching institutional completeness (churches, voluntary associations, press, even unions), separate from the host German society. Lucassen found that religiosity and nationalism were more fundamental in generating nativism and inter-group hostility than the labor antagonism.Once Italian workers in France had understood the benefit of unionism and French unions were willing to overcome their fear of Italians as strikebreakers, integration was open for most Italian immigrants. The French state, which was always more of an immigration state than Prussia, Germany or Great Britain, fostered and supported family-based immigration and thus helped Italians on their immigration trajectory with minimal nativism.

Many observers see the post-1950s wave of immigration in Europe was fundamentally different from the pre-1914 patterns. They debate the role of cultural differences, ghettos, race, Muslim fundamentalism, poor education and poverty play in creating nativism among the hosts and a caste-type underclass, more similar to white-black tensions in the US. Algerian migration to France has generated nativism, characterized by the prominence of Jean-Marie Le Pen and his National Front.

Pakistan

The Pakistani province of Sindh has seen nativist movements, promoting control for the Sindhi people over their homeland. After the 1947 Partition of India, large numbers of Muhajir people migrating from India entered the province, becoming a majority in the provincial capital city of Karachi, which formerly had an ethnically Sindhi majority. Sindhis have also voiced opposition to the promotion of Urdu, as opposed to their native tongue, Sindhi.These nativist movements are expressed through Sindhi nationalism and the Sindhudesh separatist movement. Nativist and nationalist sentiments increased greatly after the independence of Bangladesh from Pakistan in 1971.

Taiwan

Nativism flourished in Taiwan in the 1970s as a reaction against the influx of mainland Chinese to the island after the Kuomintang's defeat in 1949. Nativists felt that the political influence of mainland Chinese was disproportionately large. The term is especially found in the field of literature, where nativist literature was more traditionally minded than the modernist literature written largely by mainland Chinese.United Kingdom

London was notorious for its xenophobia in the 16th century, and conditions worsened in the 1580s. Many immigrants became disillusioned by routine threats of violence and molestation, attempts at expulsion of foreigners, and the great difficulty in acquiring English citizenship. Dutch cities proved more hospitable, and many left London permanently.Regarding the Irish in 20th-century Great Britain, Lucassen argues that the deep religious divide between the Protestants and Catholics was at the core of the ongoing estrangement of the Irish in British society.

United States

Early Republic

Nativism was a political factor in the 1790s and in the 1830s-1850s. There was little nativism in the colonial era, but for a while Benjamin Franklin was hostile to German Americans in colonial Pennsylvania; He called them "Palatine Boors." However, he reversed himself and became a supporter.Nativism became a major issue in the late 1790s, when the Federalist Party expressed its strong opposition to the French Revolution by trying to strictly limit immigration, and stretching the time to 14 years for citizenship. At the time of the Quasi-War with France in 1798, the Federalists and Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, including the Alien Act, the Naturalization Act and the Sedition Act. The movement was led by Alexander Hamilton, despite his own status as an immigrant from a small Island. Phillip Magness argues that “Hamilton’s political career might legitimately be characterized as a sustained drift into nationalistic xenophobia.” Thomas Jefferson and James Madison fought by drafting the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions. The two laws against aliens were motivated by fears of a growing Irish radical presence in Philadelphia, where they supported Jefferson. However, they were not actually enforced. President John Adams annoyed his fellow Federalists by making peace with France, and splitting his party in 1800. Jefferson was elected president, and reversed most of the hostile legislation.

1830-1860

The term "nativism" was first used by 1844: "Thousands were Naturalized expressly to oppose Nativism, and voted the Polk ticket mainly to that end."Nativism gained its name from the "Native American" parties of the 1840s and 1850s. In this context "Native" does not mean indigenous Americans or American Indians but rather those descended from the inhabitants of the original Thirteen Colonies. It impacted politics in the mid-19th century because of the large inflows of immigrants after 1845 from cultures that were different from the existing American culture. Nativists objected primarily to Irish Roman Catholics because of their loyalty to the Pope and also because of their supposed rejection of republicanism as an American ideal.

Nativist movements included the Know Nothing or American Party of the 1850s, the Immigration Restriction League of the 1890s, the anti-Asian movements in the West, resulting in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the "Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907" by which Japan's government stopped emigration to the United States. Labor unions were strong supporters of Chinese exclusion and limits on immigration, because of fears that they would lower wages and make it harder for workers to organize unions.

Historian Eric Kaufmann has suggested that American nativism has been explained primarily in psychological and economic terms due to the neglect of a crucial cultural and ethnic dimension. Furthermore, Kauffman claims that American nativism cannot be understood without reference to an American ethnic group which took shape prior to the large-scale immigration of the mid-eighteenth century.

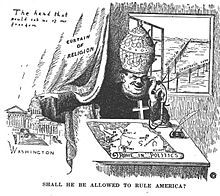

Guardians of Liberty, 1943, by Bishop Alma White

Nativist outbursts occurred in the Northeast from the 1830s to the 1850s, primarily in response to a surge of Irish Catholic immigration. In 1836, Samuel Morse ran unsuccessfully for Mayor of New York City on a Nativist ticket, receiving 1,496 votes. In New York City, an Order of United Americans was founded as a nativist fraternity, following the Philadelphia Nativist Riots of the preceding spring and summer, in December, 1844.

The Nativists went public in 1854 when they formed the 'American Party', which was especially hostile to the immigration of Irish Catholics and campaigned for laws to require longer wait time between immigration and naturalization. (The laws never passed.) It was at this time that the term "nativist" first appears, opponents denounced them as "bigoted nativists." Former President Millard Fillmore ran on the American Party ticket for the Presidency in 1856. The American Party also included many ex-Whigs who ignored nativism, and included (in the South) a few Catholics whose families had long lived in America. Conversely, much of the opposition to Catholics came from Protestant Irish immigrants and German Lutheran immigrants who were not native at all and can hardly be called "nativists."

This form of nationalism is often identified with xenophobia and anti-Catholic sentiment (anti-Papism). In Charlestown, Massachusetts, a nativist mob attacked and burned down a Catholic convent in 1834 (no one was injured). In the 1840s, small scale riots between Catholics and nativists took place in several American cities. In Philadelphia in 1844, for example, a series of nativist assaults on Catholic churches and community centers resulted in the loss of lives and the professionalization of the police force. In Louisville, Kentucky, election-day rioters killed at least 22 people in attacks on German and Irish Catholics on Aug. 6, 1855, in what became known as "Bloody Monday."

The new Republican Party kept its nativist element quiet during the 1860s, since immigrants were urgently needed for the Union Army. Immigrants from England, Scotland and Scandinavia favored the Republicans during the Third Party System, 1854-1896, while others were usually Democratic. Hostility toward Asians was very strong from the 1860s to the 1940s. Nativism experienced a revival in the 1890s, led by Protestant Irish immigrants hostile to Catholic immigration, especially the American Protective Association.

Anti-German nativism

From the 1840s to 1920 German Americans were distrusted because of their separatist social structure, their German-language schools, their attachment to their native tongue over English, and their neutrality during World War I.The Bennett Law caused a political uproar in Wisconsin in 1890, as the state government passed a law that threatened to close down hundreds of German-language elementary schools. Catholic and Lutheran Germans rallied to defeat Governor William D. Hoard. Hoard attacked German American culture and religion:

- We must fight alienism and selfish ecclesiasticism.... The parents, the pastors and the church have entered into a conspiracy to darken the understanding of the children, who are denied by cupidity and bigotry the privilege of even the free schools of the state.

In 1917–1918, a wave of nativist sentiment led to the suppression of German cultural activities in the United States, Canada and Australia. There was little violence, but many places and streets had their names changed (The city of "Berlin" in Ontario was renamed "Kitchener" after a British hero), churches switched to English for their services, and German Americans were forced to buy war bonds to show their patriotism. In Australia thousands of Germans were put into internment camps.

Anti-Chinese nativism

In the 1870s in the western states Irish Americans targeted violence against Chinese workers, driving them out of smaller towns. Denis Kearney, an immigrant from Ireland, led a mass movement in San Francisco in the 1870s that incited attacks on the Chinese there and threatened public officials and railroad owners. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was the first of many nativist acts of Congress which attempted to limit the flow of immigrants into the U.S.. The Chinese responded to it by filing false claims of American birth, enabling thousands of them to immigrate to California. The exclusion of the Chinese caused the western railroads to begin importing Mexican railroad workers in greater numbers ("traqueros").20th century

In the 1890s–1920s era nativists and labor unions campaigned for immigration restriction. A favorite plan was the literacy test to exclude workers who could not read or write their own foreign language. Congress passed literacy tests, but presidents—responding to business needs for workers—vetoed them. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge argued need for literacy tests and its implication on the new immigrants:- It is found, in the first place, that the illiteracy test will bear most heavily upon the Italians, Russians, Poles, Hungarians, Greeks, and Asiatics, and lightly, or not at all, upon English-speaking emigrants, or Germans, Scandinavians, and French. In other words, the races most affected by the illiteracy test are those whose emigration to this country has begun within the last twenty years and swelled rapidly to enormous proportions, races with which the English speaking people have never hitherto assimilated, and who are most alien to the great body of the people of the United States.

Following World War I, nativists in the twenties focused their attention on Catholics, Jews, and south-eastern Europeans and realigned their beliefs behind racial and religious nativism. The racial concern of the anti-immigration movement was linked closely to the eugenics movement that was sweeping the United States in the twenties. Led by Madison Grant's book, The Passing of the Great Race nativists grew more concerned with the racial purity of the United States. In his book, Grant argued that the American racial stock was being diluted by the influx of new immigrants from the Mediterranean, the Balkans, and the ghettos. The Passing of the Great Race reached wide popularity among Americans and influenced immigration policy in the twenties. In the 1920s a wide national consensus sharply restricted the overall inflow of immigrants, especially those from southern and eastern Europe. The second Ku Klux Klan, which flourished in the U.S. in the 1920s, used strong nativist rhetoric, but the Catholics led a counterattack.

After intense lobbying from the nativist movement the United States Congress passed the Emergency Quota Act in 1921. This bill was the first to place numerical quotas on immigration. It capped the inflow of immigrations to 357,803 for those arriving outside of the western hemisphere. However, this bill was only temporary as Congress began debating a more permanent bill.

The Emergency Quota Act was followed with the Immigration Act of 1924, a more permanent resolution. This law reduced the number of immigrants able to arrive from 357,803, the number established in the Emergency Quota Act, to 164,687. Though this bill did not fully restrict immigration, it considerably curbed the flow of immigration into the United States, especially from Southern and Eastern Europe. During the late twenties an average of 270,000 immigrants were allowed to arrive mainly because of the exemption of Canada and Latin American countries.

Fear of low-skilled immigrants flooding the labor market was an issue in the 1920s (focused on immigrants from Italy and Poland), and in the first decade of the 21st century (focused on immigrants from Mexico and Central America).

An immigration reductionism movement formed in the 1970s and continues to the present day. Prominent members often press for massive, sometimes total, reductions in immigration levels.

American nativist sentiment experienced a resurgence in the late 20th century, this time directed at undocumented workers, largely Mexican resulting in the passage of new penalties against illegal immigration in 1996.

Most immigration reductionists see Illegal immigration, principally from across the United States–Mexico border, as the more pressing concern. Authors such as Samuel Huntington have also seen recent Hispanic immigration as creating a national identity crisis and presenting insurmountable problems for US social institutions.

Noting the large-scale Mexican immigration in the Southwest, the Cold-war diplomat George F. Kennan in 2002 saw "unmistakable evidences of a growing differentiation between the cultures, respectively, of large southern and southwestern regions of this country, on the one hand", and those of "some northern regions". In the former, he warned:

- the very culture of the bulk of the population of these regions will tend to be primarily Latin-American in nature rather than what is inherited from earlier American traditions ... Could it really be that there was so little of merit [in America] that it deserves to be recklessly trashed in favor of a polyglot mix-mash?

21st century

By late 2014, the "Tea Party movement" had turned its focus away from economic issues, spending, and Obamacare, and towards President Barack Obama's immigration policies, which it saw as threatening to transform American society. It planned to defeat leading Republicans who supported immigration programs, such as Senator John McCain. A typical slogan appeared in the Tea Party Tribune: “Amnesty for Millions, Tyranny for All.” The New York Times reported:- What started five years ago as a groundswell of conservatives committed to curtailing the reach of the federal government, cutting the deficit and countering the Wall Street wing of the Republican Party has become a movement largely against immigration overhaul. The politicians, intellectual leaders and activists who consider themselves part of the Tea Party have redirected their energy from fiscal austerity and small government to stopping any changes that would legitimize people who are here illegally, either through granting them citizenship or legal status.

- Trump has been drawing on a base of alienated white working-class and middle-class voters, seeking to remake the G.O.P. into a more populist, nativist, avowedly protectionist, and semi-isolationist party that is skeptical of immigration, free trade, and military interventionism.

- Donald Trump’s nativism is a fundamental corruption of the founding principles of the Republican Party. Nativists champion the purported interests of American citizens over those of immigrants, justifying their hostility to immigrants by the use of derogatory stereotypes: Mexicans are rapists; Muslims are terrorists.

Language

Sticker sold in Colorado

American nativists have promoted English and deprecated the use of German and Spanish. English Only proponents in the late 20th century proposed an English Language Amendment (ELA), a Constitutional Amendment making English the official language of the United States, but it received limited political support.