Eco-capitalism, also known as environmental capitalism or green capitalism, is the view that capital exists in nature as "natural capital" (ecosystems that have ecological yield) on which all wealth depends, and therefore, market-based government policy instruments (such as a carbon tax) should be used to resolve environmental problems.

The term "Blue Greens" is often applied to those who espouse eco-capitalism. It is considered as the right-wing equivalent to Red Greens.

History

The roots of eco-capitalism can be traced back to the late 1960s. The "Tragedy of the Commons", an essay published in 1968 in Science by Garrett Hardin, claimed the inevitability of malthusian catastrophe

due to liberal or democratic government's policies to leave family size

matters to the family, and enabling the welfare state to willingly care

for potential human overpopulation.

Hardin argued that if families were given freedom of choice in the

matter, but were removed from a welfare state, parents choosing to

overbear would not have the resources to provide for their "litter",

thus solving the problem of overpopulation. This represents an early

argument made from an eco-capitalist standpoint: overpopulation would

technically be solved by a free market. John Baden, a collaborator with Garrett Hardin on other works including Managing the Commons, founded the Political Economy Research Center (now called the Property and Environment Research Center

) in 1982. As one of the first eco-capitalist organizations created,

PERC's ongoing mission is "improving environmental quality through

property rights and markets". The most popular eco-capitalist idea was emissions trading, or more commonly, cap and trade.

Emissions trading, a market-based approach that allows polluting

entities to purchase or be allocated permits, began being researched in

the late 1960s. International emissions trading was significantly

popularized in the 1990s when the United Nations adopted the Kyoto Protocol in 1997.

Eco-capitalist theorists

- Terry L. Anderson is a graduate of the University of Montana, and received his Ph.D from Washington University. Anderson is currently serving as the co-chair of the Hoover Institution's Property Rights, Freedom and Prosperity task force. Anderson advocates that free markets can be both economically beneficial and environmentally protective. Anderson specializes in how markets impact Native American communities and their economies.

- Bruce Yandle, a graduate of Mercer University, attended Georgia State University where he earned a MBA and PhD. Yandle is currently serving as dean emeritus of Clemson University's college of business. Yandle is prominent in the field of eco-capitalism for his story of the "Bootlegger and the Baptist". Yandle's theory of the Bootlegger and the Baptist posits that ethical groups, religious institutions and business captains can align their organizations in the interest of regulation and economic growth.

- Paul Hawken decided at a young age to dedicate his life to making business eco-friendlier. Hawken's is the architect of the United States first natural foods company, Erewhon Trading Company where all products were organically composed. Hawken's continued to make an impact on the business world by founding the research organization, Natural Capital Institute, and developed, Wiser Earth, a program focused on providing a platform for all to communicate about the environment. Not only has Paul Hawken set a good example for how to transform economy into eco-capitalism, but also has authored hundreds of publications, including four best selling books. In his writings, Hawken stresses that many smart ecological options are out there for businesses that will help save the environment, while also continuing to bring economic profit. One idea discussed in his book, Natural Capitalism: Creating the Next Industrial Revolution, is the possibility of developing lightweight, electricity-powered cars as an alternative to our current transportation issue. Hawken attributes the hesitancy of adopting these options to lack of knowledge of these alternatives and high initial costs. Paul Hawken is now the head of OneSun, Inc., an energy corporation concentrated on low-cost solar.

- Lester Brown began his career as a tomato farmer in New Jersey, until earning his degree at Rutgers University and traveling to a rural India for a six-month study of the country's food and population crisis. From this point on, Brown's focus was mostly on finding alternatives that would solve the world’s population and resources problem. With financial support from Rockefeller Brothers Fund, Brown created the Worldwatch Institute, the first dedicated to researching global environmental problems. In 2001, Brown found the Earth Policy Institute, an organization that outlined a vision for creating an environmentally sustainable economy. Over the course of his career, Lester Brown has authored over 50 books and received 25 honorary degrees. In his publications, Brown discusses how the key to an eco-friendly economy is an honest market and replacing harmful aspects of the environment, like fossil fuels with renewable energy. On June 2015, Lester Brown retired from Earth Policy and closed the institute.

Transition to eco-capitalism

The ideology of eco-capitalism was adopted to satisfy two competing needs:

- the desire for generating profit by businesses in a capitalist society and

- the urgency for proper actions to address a struggling environment negatively impacted by human activity.

Under the doctrine of eco-capitalism, businesses commodify the act of addressing environmental issues.

The following are common principles in the transition to eco-capitalism.

Externalities: Correcting of a free market failure

A central part of eco-capitalism is to correct for the market failure seen in the externalization of pollution. By treating the issue of pollution as an externality

it has allowed the market to minimize the degree of accountability. To

correct for this market failure eco-capitalism would have to internalize

this cost. A prime example of this shift towards internalizing

externalities is seen in the adoption of a system for carbon trading. In a system like this people are forced to factor the pollution cost into their expenses.

This system as well as other systems of internalization function on

large and small scales(often times both are tightly connected). On a

corporate scale, the government can regulate carbon emissions

and other polluting factors in business practices forcing companies to

either reduce their pollution levels, externalize these costs onto their

consumers by raising the cost of their goods/services, and/or a

combination of the two.

These kinds of systems can also be effective in indirectly creating a

more environmentally conscious consumer base. As the companies who are

creating the most pollution face falling profit levels and rising prices

their consumers and investors are inclined to take their business

elsewhere. This migration of investment and revenue would then be

expected to make its way to business who have already incorporated the

minimization of pollution into their business model thus allowing them

to provide lower prices and higher profit margins attracting the

migrating consumers and investors.

Green consumption

At the conception of the ideology, major theorists of eco-capitalism,

Paul Hawken, Lester Brown, and Francis Cairncross, saw an opportunity

to establish a different approach to environmentalism in a capitalist

society.

These theorists thought that not only producers but also consumers

could shoulder the social responsibility of environmental restoration if

"green technology, green taxes, green labeling, and eco-conscious

shopping" existed.

The resulting "shopping our way to sustainability" mentality encouraged

the development of organic farming, renewable energy, green

certifications as well as other eco-friendly practices.

A 2015 report from Nielsen lends credence to this theory.

According to the report, consumers have more brand loyalty and are

willing to pay higher prices for a product that is perceived as being

sustainable. This is especially true among Millenials and Generation Z. These generations currently make up 48% of the global marketplace

and still haven't hit their peak spending levels. As these generations'

preferences continue to shape how businesses operate and market

themselves, they could drive a continued shift toward green consumption.

According to the Annual Review of Environmental Resources, "the

focus of policy makers, businesses, and researchers has mostly been on

the latter (consuming differently), with relatively little attention

paid to consuming less".

A review of how to encourage sustainable consumption from the

University of Surrey shows that, "Government policies send important

signals to consumers about institutional goals

and national priorities." Governments can pull a variety of levers to signal this including product, trading, building, media, and marketing standards.

Carbon trading

Creating perhaps the first major eco-capitalist endorsement, many

political and economic institutions support a system of pollution

credits. Such a system, which assigns property rights to emissions, is

considered to be the most "efficient and effective" way for regulating greenhouse gas emissions in the current neoliberal global economy.

Especially in the case of tradable pollution credits, the resulting

market-based system of emissions regulation is believed to motivate

businesses to invest in technology that reduce greenhouse gas emissions

using positive reinforcement (i.e. ability to trade unused credits) and punishment (i.e. the need to buy more credits).

Full cost accounting

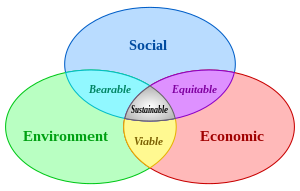

Environmental full-cost accounting

explains corporate actions on the basis of the triple bottom line,

which is best summarized as "people, planet, and profit". As a concept

of corporate social responsibility, full cost accounting not only

considers social and economic costs and benefits but also the

environmental implications of specific corporate actions.

A breakdown of accounting methodologies by what they include.

While there has been progress in measuring the cost of harm to the health of individuals and the environment,

the interaction of environmental, social, and health effects makes

measurement difficult. Measurement attempts can be broadly categorized

as either behavioral in nature, like hedonic pricing, or dose-response which looks at indirect effects. A standardized measurement of these costs has yet to emerge.

This should not be confused with the full-cost method used by

organizations searching for oil and gas that "does not differentiate

between operating expenses associated with successful and unsuccessful

exploration projects".

Genuine progress indicator

The

current standard of using the gross domestic product (GDP) as an

indicator of welfare is criticized for being inaccurate. An alternative

to GDP, the genuine progress indicator

compensates for the shortcomings of the GDP as a welfare indicator by

accounting for environmental harms as well as other factors that affect

consumption, such as crime and income inequality.

Criticisms

Majority of the criticism from traditionally unregulated capitalism

is due to eco-capitalism's increased regulation. Pollution credits (as a

means for regulating greenhouse gas emissions) is traditionally at odds

with economically conservative ideologies. Elements of unregulated

capitalism prefer environmental issues to be addressed by individuals

who may allocate their own income and wealth, oppose the commodification

of by-products like carbon emissions, and emphasize positive incentives

to maintain resources through free-market competition and

entrepreneurship.

Proponents of eco-capitalism view environmental reform like

pollution credits as a more transformative and progressive system.

According to these Proponents, since free market capitalism as

inherently expansionist in tendency, ignoring environmental

responsibility is a danger to the environment. Approximately 36% of Americans are deeply concerned about climate issues. Proponents of Eco Capitalism typically favor political environmentalism,

which emphasizes negative incentives like regulation and taxes to

encourage the conservation of resources and prevent environmental harm.

Political theorist, Antonio Gramsci, cites theories of common sense,

which suggests that, in general, free market capitalism absent of

environmental reform, is ingrained in the minds of its members as the

only viable and successful form of economic organization through cultural hegemony.

Therefore, the proposal of any alternate economic system, like

eco-capitalism, must overcome the predominant common sense and economic

status quo in order to develop opposing theories. Nonetheless, movements

in the United States and abroad have continued to push for reforms to

protect the environment in current capitalistic systems.

Another political theorist, Daniel Tanuro, explains, in his book

"Green Capitalism: Why it Can't Work", that for green capitalism to be

successful, it would have to replace current mainstream capitalism with

Eco-socialist methods, while defying corporate interests:

If by ‘green capitalism’ we understand a system in which the qualitative, social and ecological parameters are taken in account by the numerous competing capitals, that is to say even within economic activity as an endogenous mechanism, then we are completely deluded. In fact, we would be talking about a form of capitalism in which the law of value was no longer in operation, which is a contradiction in terms

However, Tanuro adds that social and economical change to the current

capitalist systems is necessary, because technology will invariably

increase emissions as manufacturing processes and distribution systems

progress. Tanuro argues for changes in three areas:

- Use of transportation methods

- Agriculture and dietary changes

- Overall consumer lifestyle and market spending

Despite this argument, critics still claim that green consumption,

sustainable behavior on the part of the consumer, is not enough to be

instituted as a socio-environmental solution. In accordance with hegemony,

capitalism agrees that the government has little control over market

and buyers, sellers, and consumers ultimately drive the market. In

contrast, in green capitalism, the government would have more control

therefore; consumers do not have direct power over the market, and

should not be held accountable. Thus, going against the established monetary system of capitalism in the U.S. and spread throughout the globally.

Environmental Scholar Bill McKibben proposes "full scale climate mobilization" to address environmental decay.

During World War II, vehicle manufacturers and general goods

manufacturers shifted to producing weapons, military vehicles and war

time goods. McKibben argues that, to combat environmental change, the

American Military Industrial Complex and other national arms producers

could shift to producing solar panels, wind turbines and other

environmental products in an Eco-Capitalist system.

Scholar Elliot Sperber counters McKibben's argument, citing that

industrial environmental mobilization favoring eco-capitalism would

exacerbate socioeconomic stratification.

Sperber counters the notion that "full scale climate mobilization" and

the production it implies is the best immediate solution for addressing

climate change. Because Eco Capitalism is still capitalistic, it relies

on production of goods. Sperber argues for the production of fewer goods

(i.e. fewer plastics, fewer vehicles) to minimize carbon footprints.

Apparent criticisms have risen concerns and need for social and

economical transformation on both ends of the political and theoretical

divide. Nonetheless, they have shaped the way the majority public has

viewed and contributed to capitalism and continue to both actively

change the innate structure of the economic system and enhance it for

further economic stability.

Appeal of renewable energy in the capitalist market

Tom

Randall, a correspondent specializing in renewable energy for

Bloomberg, calls to attention that wind and solar (energy sources) are

"outperforming" fossil fuels.

In terms of investments, clean energy outperforms both gas and coal by a

2-1 margin. This positive margin may be attributed to the consistently

falling price of renewable energy production. Renewable energy sources

hold assertive advantages over fossil fuels because they exist as

technologies, not fuels. As time proceeds, renewable energy becomes

inevitably more efficient as technology adapts. Technologies for

extracting fuels may change, but the fuels remain as constants. Both the

solar and wind industries have proven growth over time: Over the last

15 years, the solar industry has doubled seven times and the wind

industry has doubled four times.

In contrast, the fossil fuel industry has declined over the last 15

years. America's coal industry has lost 75 percent of its value within

the past few years.

Renewable energy sources also gain advantages over the fossil fuel industry through international governmental support. Globally, governments implement subsidies to boost the renewable energy industry. Concurrently, various global efforts fight against fossil fuel production and use.

The demand for renewable energy sources has skyrocketed in the last 15

years, while fossil fuels have drastically fallen in demand (in

capitalist societies).

The worldwide concern of climate change (also known as global warming) is notably the largest contributor to the green energy industry's rapid acceleration, just as it is largely responsible for the decline of the fossil fuel industry.

The overwhelming scientific consensus of climate change's reality and

its potential catastrophic effects have caused a large part of the

world's population to respond with panic and immediate action. While the

world's response has been strong, environmentalists and climate

scientists do not believe the response has been strong enough to counter

climate change's effects, and that the transition from fossil fuels to

renewable energy sources is moving far too slowly.

The global efforts and concerns of both governments and

individuals to take action regarding implementing and transforming a

society's energy sources from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources

show the enormous potential of the green energy market. This potential

is seen in the countless renewable energy projects under way. Currently,

there are over 4,000 major solar projects being implemented. These, and all renewable energy projects, set goals of long-term economic benefit.

The Global Apollo Programme,

set up by both economists and scientists, has a goal of creating a

solar capability that can stand as a cheaper alternative to coal-fueled

power plants by 2025. In capitalist markets, solar energy has the very real potential of becoming a direct competitor to coal plants in less than a decade.

Barriers to transition

While

there can be many barriers to the transition to a eco-capitalist

system, one of the most daunting and forgotten is the systemic barrier

that can be created by former models. Dimitri Zenghelis explores the

idea of path dependence and the how continuing to build infrastructure

without foresight seriously impedes the implementation and benefits of

future innovations.

Zenghelis uses the term “locked-in” to describe situations where the

full implementation of a new innovation cannot be seen because an

earlier infrastructure prevents it from functioning well. This barrier

is exemplified in older cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco and New

York where the infrastructure was designed around urban sprawl to

accommodate private vehicles. The sprawl has been researched with the

results returning that the moving forward mega-cities need to be

constructed as eco-cities if the hope of curving emission levels down is

going to have any hope.