Historically, the second law was an empirical finding that was accepted as an axiom of thermodynamic theory. Statistical mechanics, classical or quantum, explains the microscopic origin of the law.

The second law has been expressed in many ways. Its first formulation is credited to the French scientist Sadi Carnot, who in 1824 showed that there is an upper limit to the efficiency of conversion of heat to work, in a heat engine.

The second law has been expressed in many ways. Its first formulation is credited to the French scientist Sadi Carnot, who in 1824 showed that there is an upper limit to the efficiency of conversion of heat to work, in a heat engine.

Introduction

Heat flow from hot water to cold water.

The first law of thermodynamics provides the basic definition of internal energy, associated with all thermodynamic systems, and states the rule of conservation of energy. The second law is concerned with the direction of natural processes.

It asserts that a natural process runs only in one sense, and is not

reversible. For example, heat always flows spontaneously from hotter to

colder bodies, and never the reverse, unless external work is performed

on the system. The explanation of the phenomena was given in terms of entropy. Total entropy (S)

can never decrease over time for an isolated system because the entropy

of an isolated system spontaneously evolves toward thermodynamic

equilibrium: the entropy should stay the same or increase.

In a fictive reversible process, an infinitesimal increment in the entropy (dS) of a system is defined to result from an infinitesimal transfer of heat (δQ) to a closed system (which allows the entry or exit of energy – but not mass transfer) divided by the common temperature (T) of the system in equilibrium and the surroundings which supply the heat:

Different notations are used for infinitesimal amounts of heat (δ) and infinitesimal amounts of entropy (d) because entropy is a function of state,

while heat, like work, is not. For an actually possible infinitesimal

process without exchange of mass with the surroundings, the second law

requires that the increment in system entropy fulfills the inequality

This is because a general process for this case may include work

being done on the system by its surroundings, which can have frictional

or viscous effects inside the system, because a chemical reaction may be

in progress, or because heat transfer actually occurs only

irreversibly, driven by a finite difference between the system

temperature (T) and the temperature of the surroundings (Tsurr). Note that the equality still applies for pure heat flow,

which is the basis of the accurate determination of the absolute

entropy of pure substances from measured heat capacity curves and

entropy changes at phase transitions, i.e. by calorimetry. Introducing a set of internal variables to describe the deviation of a thermodynamic system in physical equilibrium (with the required well-defined uniform pressure P and temperature T) from the chemical equilibrium state, one can record the equality

The second term represents work of internal variables that can be

perturbed by external influences, but the system cannot perform any

positive work via internal variables. This statement introduces the

impossibility of the reversion of evolution of the thermodynamic system

in time and can be considered as a formulation of the second principle of thermodynamics – the formulation, which is, of course, equivalent to the formulation of the principle in terms of entropy.

The zeroth law of thermodynamics in its usual short statement allows recognition that two bodies in a relation of thermal equilibrium have the same temperature, especially that a test body has the same temperature as a reference thermometric body. For a body in thermal equilibrium with another, there are indefinitely many empirical temperature scales, in general respectively depending on the properties of a particular reference thermometric body. The second law allows a distinguished temperature scale, which defines an absolute, thermodynamic temperature, independent of the properties of any particular reference thermometric body.

Various statements of the law

The second law of thermodynamics may be expressed in many specific ways, the most prominent classical statements being the statement by Rudolf Clausius (1854), the statement by Lord Kelvin (1851), and the statement in axiomatic thermodynamics by Constantin Carathéodory

(1909). These statements cast the law in general physical terms citing

the impossibility of certain processes. The Clausius and the Kelvin

statements have been shown to be equivalent.

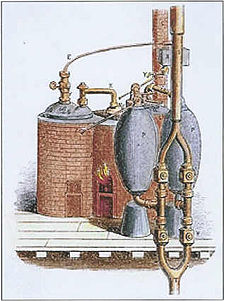

Carnot's principle

The historical origin of the second law of thermodynamics was in Carnot's principle. It refers to a cycle of a Carnot heat engine,

fictively operated in the limiting mode of extreme slowness known as

quasi-static, so that the heat and work transfers are between subsystems

that are always in their own internal states of thermodynamic

equilibrium. The Carnot engine is an idealized device of special

interest to engineers who are concerned with the efficiency of heat

engines. Carnot's principle was recognized by Carnot at a time when the caloric theory of heat was seriously considered, before the recognition of the first law of thermodynamics,

and before the mathematical expression of the concept of entropy.

Interpreted in the light of the first law, it is physically equivalent

to the second law of thermodynamics, and remains valid today. It states

The efficiency of a quasi-static or reversible Carnot cycle depends only on the temperatures of the two heat reservoirs, and is the same, whatever the working substance. A Carnot engine operated in this way is the most efficient possible heat engine using those two temperatures.

Clausius statement

The German scientist Rudolf Clausius laid the foundation for the second law of thermodynamics in 1850 by examining the relation between heat transfer and work. His formulation of the second law, which was published in German in 1854, is known as the Clausius statement:

Heat can never pass from a colder to a warmer body without some other change, connected therewith, occurring at the same time.

The statement by Clausius uses the concept of 'passage of heat'. As

is usual in thermodynamic discussions, this means 'net transfer of

energy as heat', and does not refer to contributory transfers one way

and the other.

Heat cannot spontaneously flow from cold regions to hot regions

without external work being performed on the system, which is evident

from ordinary experience of refrigeration, for example. In a

refrigerator, heat flows from cold to hot, but only when forced by an

external agent, the refrigeration system.

Kelvin statement

Lord Kelvin expressed the second law as

It is impossible, by means of inanimate material agency, to derive mechanical effect from any portion of matter by cooling it below the temperature of the coldest of the surrounding objects.

Equivalence of the Clausius and the Kelvin statements

Derive Kelvin Statement from Clausius Statement

Suppose there is an engine violating the Kelvin statement: i.e., one

that drains heat and converts it completely into work in a cyclic

fashion without any other result. Now pair it with a reversed Carnot engine

as shown by the figure. The net and sole effect of this newly created

engine consisting of the two engines mentioned is transferring heat from the cooler reservoir to the hotter one, which violates the Clausius statement(This is a consequence of the first law of thermodynamics, as for the total system's energy to remain the same, , so therefore

). Thus a violation of the Kelvin statement implies a violation of the

Clausius statement, i.e. the Clausius statement implies the Kelvin

statement. We can prove in a similar manner that the Kelvin statement

implies the Clausius statement, and hence the two are equivalent.

Planck's proposition

Planck

offered the following proposition as derived directly from experience.

This is sometimes regarded as his statement of the second law, but he

regarded it as a starting point for the derivation of the second law.

It is impossible to construct an engine which will work in a complete cycle, and produce no effect except the raising of a weight and cooling of a heat reservoir.

Relation between Kelvin's statement and Planck's proposition

It is almost customary in textbooks to speak of the "Kelvin-Planck statement" of the law, as for example in the text by ter Haar and Wergeland.

The Kelvin–Planck statement (or the heat engine statement) of the second law of thermodynamics states that

It is impossible to devise a cyclically operating device, the sole effect of which is to absorb energy in the form of heat from a single thermal reservoir and to deliver an equivalent amount of work.

Planck's statement

Planck stated the second law as follows.

Every process occurring in nature proceeds in the sense in which the sum of the entropies of all bodies taking part in the process is increased. In the limit, i.e. for reversible processes, the sum of the entropies remains unchanged.

Rather like Planck's statement is that of Uhlenbeck and Ford for irreversible phenomena.

... in an irreversible or spontaneous change from one equilibrium state to another (as for example the equalization of temperature of two bodies A and B, when brought in contact) the entropy always increases.

Principle of Carathéodory

Constantin Carathéodory

formulated thermodynamics on a purely mathematical axiomatic

foundation. His statement of the second law is known as the Principle of

Carathéodory, which may be formulated as follows:

In every neighborhood of any state S of an adiabatically enclosed system there are states inaccessible from S.

With this formulation, he described the concept of adiabatic accessibility for the first time and provided the foundation for a new subfield of classical thermodynamics, often called geometrical thermodynamics. It follows from Carathéodory's principle that quantity of energy quasi-statically transferred as heat is a holonomic process function, in other words, .

Though it is almost customary in textbooks to say that

Carathéodory's principle expresses the second law and to treat it as

equivalent to the Clausius or to the Kelvin-Planck statements, such is

not the case. To get all the content of the second law, Carathéodory's

principle needs to be supplemented by Planck's principle, that isochoric

work always increases the internal energy of a closed system that was

initially in its own internal thermodynamic equilibrium.

Planck's principle

In 1926, Max Planck wrote an important paper on the basics of thermodynamics. He indicated the principle

The internal energy of a closed system is increased by an adiabatic process, throughout the duration of which, the volume of the system remains constant.

This formulation does not mention heat and does not mention

temperature, nor even entropy, and does not necessarily implicitly rely

on those concepts, but it implies the content of the second law. A

closely related statement is that "Frictional pressure never does

positive work." Using a now-obsolete form of words, Planck himself wrote: "The production of heat by friction is irreversible."

Not mentioning entropy, this principle of Planck is stated in

physical terms. It is very closely related to the Kelvin statement given

just above. It is relevant that for a system at constant volume and mole numbers,

the entropy is a monotonic function of the internal energy.

Nevertheless, this principle of Planck is not actually Planck's

preferred statement of the second law, which is quoted above, in a

previous sub-section of the present section of this present article, and

relies on the concept of entropy.

A statement that in a sense is complementary to Planck's

principle is made by Borgnakke and Sonntag. They do not offer it as a

full statement of the second law:

... there is only one way in which the entropy of a [closed] system can be decreased, and that is to transfer heat from the system.

Differing from Planck's just foregoing principle, this one is

explicitly in terms of entropy change. Removal of matter from a system

can also decrease its entropy.

Statement for a system that has a known expression of its internal energy as a function of its extensive state variables

The second law has been shown to be equivalent to the internal energy U being a weakly convex function, when written as a function of extensive properties (mass, volume, entropy, ...).

Corollaries

Perpetual motion of the second kind

Before the establishment of the second law, many people who were

interested in inventing a perpetual motion machine had tried to

circumvent the restrictions of first law of thermodynamics

by extracting the massive internal energy of the environment as the

power of the machine. Such a machine is called a "perpetual motion

machine of the second kind". The second law declared the impossibility

of such machines.

Carnot theorem

Carnot's theorem

(1824) is a principle that limits the maximum efficiency for any

possible engine. The efficiency solely depends on the temperature

difference between the hot and cold thermal reservoirs. Carnot's theorem

states:

- All irreversible heat engines between two heat reservoirs are less efficient than a Carnot engine operating between the same reservoirs.

- All reversible heat engines between two heat reservoirs are equally efficient with a Carnot engine operating between the same reservoirs.

In his ideal model, the heat of caloric converted into work could be

reinstated by reversing the motion of the cycle, a concept subsequently

known as thermodynamic reversibility.

Carnot, however, further postulated that some caloric is lost, not

being converted to mechanical work. Hence, no real heat engine could

realise the Carnot cycle's reversibility and was condemned to be less efficient.

Though formulated in terms of caloric, rather than entropy, this was an early insight into the second law.

Clausius inequality

The Clausius theorem (1854) states that in a cyclic process

The equality holds in the reversible case and the strict inequality holds in the irreversible case. The reversible case is used to introduce the state function entropy. This is because in cyclic processes the variation of a state function is zero from state functionality.

Thermodynamic temperature

For an arbitrary heat engine, the efficiency is:

- ,

where Wn is for the net work done per cycle. Thus the efficiency depends only on qC/qH.

Carnot's theorem states that all reversible engines operating between the same heat reservoirs are equally efficient.

Thus, any reversible heat engine operating between temperatures T1 and T2 must have the same efficiency, that is to say, the efficiency is the function of temperatures only:

In addition, a reversible heat engine operating between temperatures T1 and T3 must have the same efficiency as one consisting of two cycles, one between T1 and another (intermediate) temperature T2, and the second between T2 andT3. This can only be the case if

Now consider the case where is a fixed reference temperature: the temperature of the triple point of water. Then for any T2 and T3,

Therefore, if thermodynamic temperature is defined by

- ,

then the function f, viewed as a function of thermodynamic temperature, is simply

and the reference temperature T1 will have the

value 273.16. (Any reference temperature and any positive numerical

value could be used – the choice here corresponds to the Kelvin scale.)

Entropy

According to the Clausius equality, for a reversible process

- .

That means the line integral is path independent for reversible processes. So we can define a state function S called entropy, which for a reversible process or for pure heat transfer satisfies

- .

With this we can only obtain the difference of entropy by integrating

the above formula. To obtain the absolute value, we need the third law of thermodynamics, which states that S = 0 at absolute zero for perfect crystals.

For any irreversible process, since entropy is a state function,

we can always connect the initial and terminal states with an imaginary

reversible process and integrating on that path to calculate the

difference in entropy.

Now reverse the reversible process and combine it with the said irreversible process. Applying the Clausius inequality on this loop,

- .

Thus,

- ,

where the equality holds if the transformation is reversible.

Energy, available useful work

An important and revealing idealized special case is to consider

applying the Second Law to the scenario of an isolated system (called

the total system or universe), made up of two parts: a sub-system of

interest, and the sub-system's surroundings. These surroundings are

imagined to be so large that they can be considered as an unlimited heat reservoir at temperature TR and pressure PR – so that no matter how much heat is transferred to (or from) the sub-system, the temperature of the surroundings will remain TR; and no matter how much the volume of the sub-system expands (or contracts), the pressure of the surroundings will remain PR.

Whatever changes to dS and dSR occur in the entropies of the sub-system and the surroundings individually, according to the Second Law the entropy Stot of the isolated total system must not decrease:

- .

According to the first law of thermodynamics, the change dU in the internal energy of the sub-system is the sum of the heat δq added to the sub-system, less any work δw done by the sub-system, plus any net chemical energy entering the sub-system d ∑μiRNi, so that:

- ,

where μiR are the chemical potentials of chemical species in the external surroundings. Now the heat leaving the reservoir and entering the sub-system is

- ,

where we have first used the definition of entropy in classical

thermodynamics (alternatively, in statistical thermodynamics, the

relation between entropy change, temperature and absorbed heat can be

derived); and then the Second Law inequality from above.

It therefore follows that any net work δw done by the sub-system must obey

- .

It is useful to separate the work δw done by the subsystem into the useful work δwu that can be done by the sub-system, over and beyond the work pR dV

done merely by the sub-system expanding against the surrounding

external pressure, giving the following relation for the useful work

(exergy) that can be done:

- .

It is convenient to define the right-hand-side as the exact derivative of a thermodynamic potential, called the availability or exergy E of the subsystem,

- .

The Second Law therefore implies that for any process which can be

considered as divided simply into a subsystem, and an unlimited

temperature and pressure reservoir with which it is in contact,

- ,

i.e. the change in the subsystem's exergy plus the useful work done by the subsystem (or, the change in the subsystem's exergy less any work, additional to that done by the pressure reservoir, done on the system) must be less than or equal to zero.

In sum, if a proper infinite-reservoir-like reference state is chosen as the system surroundings in the real world, then the Second Law predicts a decrease in E for an irreversible process and no change for a reversible process.

- Is equivalent to .

This expression together with the associated reference state permits a design engineer working at the macroscopic scale (above the thermodynamic limit) to utilize the Second Law without directly measuring or considering entropy change in a total isolated system. Those changes have already been considered by the assumption that the

system under consideration can reach equilibrium with the reference

state without altering the reference state. An efficiency for a process

or collection of processes that compares it to the reversible ideal may

also be found.

This approach to the Second Law is widely utilized in engineering practice, environmental accounting, systems ecology, and other disciplines.

The second law in chemical thermodynamics

For a spontaneous chemical process in a closed system at constant temperature and pressure without non-PV work, the Clausius inequality ΔS > Q/Tsurr transforms into a condition for the change in Gibbs free energy

- ,

or dG < 0. For a similar process at constant temperature and volume, the change in Helmholtz free energy must be negative, .

Thus, a negative value of the change in free energy (G or A) is a

necessary condition for a process to be spontaneous. This is the most

useful form of the second law of thermodynamics in chemistry, where

free-energy changes can be calculated from tabulated enthalpies of

formation and standard molar entropies of reactants and products. The chemical equilibrium condition at constant T and p without electrical work is dG = 0.

History

Nicolas Léonard Sadi Carnot in the traditional uniform of a student of the École Polytechnique.

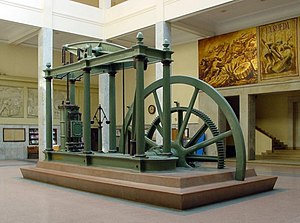

The first theory of the conversion of heat into mechanical work is due to Nicolas Léonard Sadi Carnot

in 1824. He was the first to realize correctly that the efficiency of

this conversion depends on the difference of temperature between an

engine and its environment.

Recognizing the significance of James Prescott Joule's work on the conservation of energy, Rudolf Clausius was the first to formulate the second law during 1850, in this form: heat does not flow spontaneously from cold to hot bodies. While common knowledge now, this was contrary to the caloric theory

of heat popular at the time, which considered heat as a fluid. From

there he was able to infer the principle of Sadi Carnot and the

definition of entropy (1865).

Established during the 19th century, the Kelvin-Planck statement of the Second Law says, "It is impossible for any device that operates on a cycle to receive heat from a single reservoir and produce a net amount of work." This was shown to be equivalent to the statement of Clausius.

The ergodic hypothesis is also important for the Boltzmann

approach. It says that, over long periods of time, the time spent in

some region of the phase space of microstates with the same energy is

proportional to the volume of this region, i.e. that all accessible

microstates are equally probable over a long period of time.

Equivalently, it says that time average and average over the statistical

ensemble are the same.

There is a traditional doctrine, starting with Clausius, that

entropy can be understood in terms of molecular 'disorder' within a macroscopic system. This doctrine is obsolescent.

Account given by Clausius

Rudolf Clausius

In 1856, the German physicist Rudolf Clausius stated what he called the "second fundamental theorem in the mechanical theory of heat" in the following form:

- ,

where Q is heat, T is temperature and N is the

"equivalence-value" of all uncompensated transformations involved in a

cyclical process. Later, in 1865, Clausius would come to define

"equivalence-value" as entropy. On the heels of this definition, that

same year, the most famous version of the second law was read in a

presentation at the Philosophical Society of Zurich on April 24, in

which, in the end of his presentation, Clausius concludes:

The entropy of the universe tends to a maximum.

This statement is the best-known phrasing of the second law. Because of the looseness of its language, e.g. universe,

as well as lack of specific conditions, e.g. open, closed, or isolated,

many people take this simple statement to mean that the second law of

thermodynamics applies virtually to every subject imaginable. This is

not true; this statement is only a simplified version of a more extended

and precise description.

In terms of time variation, the mathematical statement of the second law for an isolated system undergoing an arbitrary transformation is:

- ,

where

- S is the entropy of the system and

- t is time.

The equality sign applies after equilibration. An alternative way of formulating of the second law for isolated systems is:

- with ,

with the sum of the rate of entropy production by all processes inside the system. The advantage of this formulation is that it shows the effect of the entropy production.

The rate of entropy production is a very important concept since it

determines (limits) the efficiency of thermal machines. Multiplied with

ambient temperature it gives the so-called dissipated energy .

The expression of the second law for closed systems (so, allowing

heat exchange and moving boundaries, but not exchange of matter) is:

- with .

Here

- is the heat flow into the system

- is the temperature at the point where the heat enters the system.

The equality sign holds in the case that only reversible processes

take place inside the system. If irreversible processes take place

(which is the case in real systems in operation) the >-sign holds.

If heat is supplied to the system at several places we have to take the

algebraic sum of the corresponding terms.

For open systems (also allowing exchange of matter):

- with .

Here

is the flow of entropy into the system associated with the flow of

matter entering the system. It should not be confused with the time

derivative of the entropy. If matter is supplied at several places we

have to take the algebraic sum of these contributions.

Statistical mechanics

Statistical mechanics

gives an explanation for the second law by postulating that a material

is composed of atoms and molecules which are in constant motion. A

particular set of positions and velocities for each particle in the

system is called a microstate

of the system and because of the constant motion, the system is

constantly changing its microstate. Statistical mechanics postulates

that, in equilibrium, each microstate that the system might be in is

equally likely to occur, and when this assumption is made, it leads

directly to the conclusion that the second law must hold in a

statistical sense. That is, the second law will hold on average, with a

statistical variation on the order of 1/√N where N

is the number of particles in the system. For everyday (macroscopic)

situations, the probability that the second law will be violated is

practically zero. However, for systems with a small number of particles,

thermodynamic parameters, including the entropy, may show significant

statistical deviations from that predicted by the second law. Classical

thermodynamic theory does not deal with these statistical variations.

Derivation from statistical mechanics

The first mechanical argument of the Kinetic theory of gases that molecular collisions entail an equalization of temperatures and hence a tendency towards equilibrium was due to James Clerk Maxwell in 1860; Ludwig Boltzmann with his H-theorem of 1872 also argued that due to collisions gases should over time tend toward the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution.

Due to Loschmidt's paradox, derivations of the Second Law have to make an assumption regarding the past, namely that the system is uncorrelated at some time in the past; this allows for simple probabilistic treatment. This assumption is usually thought as a boundary condition,

and thus the second Law is ultimately a consequence of the initial

conditions somewhere in the past, probably at the beginning of the

universe (the Big Bang), though other scenarios have also been suggested.

Given these assumptions, in statistical mechanics, the Second Law is not a postulate, rather it is a consequence of the fundamental postulate,

also known as the equal prior probability postulate, so long as one is

clear that simple probability arguments are applied only to the future,

while for the past there are auxiliary sources of information which tell

us that it was low entropy.

The first part of the second law, which states that the entropy of a

thermally isolated system can only increase, is a trivial consequence of

the equal prior probability postulate, if we restrict the notion of the

entropy to systems in thermal equilibrium. The entropy of an isolated

system in thermal equilibrium containing an amount of energy of is:

- ,

where is the number of quantum states in a small interval between and . Here

is a macroscopically small energy interval that is kept fixed. Strictly

speaking this means that the entropy depends on the choice of .

However, in the thermodynamic limit (i.e. in the limit of infinitely

large system size), the specific entropy (entropy per unit volume or per

unit mass) does not depend on .

Suppose we have an isolated system whose macroscopic state is

specified by a number of variables. These macroscopic variables can,

e.g., refer to the total volume, the positions of pistons in the system,

etc. Then

will depend on the values of these variables. If a variable is not

fixed, (e.g. we do not clamp a piston in a certain position), then

because all the accessible states are equally likely in equilibrium, the

free variable in equilibrium will be such that is maximized as that is the most probable situation in equilibrium.

If the variable was initially fixed to some value then upon

release and when the new equilibrium has been reached, the fact the

variable will adjust itself so that

is maximized, implies that the entropy will have increased or it will

have stayed the same (if the value at which the variable was fixed

happened to be the equilibrium value).

Suppose we start from an equilibrium situation and we suddenly remove a

constraint on a variable. Then right after we do this, there are a

number

of accessible microstates, but equilibrium has not yet been reached, so

the actual probabilities of the system being in some accessible state

are not yet equal to the prior probability of .

We have already seen that in the final equilibrium state, the entropy

will have increased or have stayed the same relative to the previous

equilibrium state. Boltzmann's H-theorem, however, proves that the quantity H increases monotonically as a function of time during the intermediate out of equilibrium state.

Derivation of the entropy change for reversible processes

The second part of the Second Law states that the entropy change of a system undergoing a reversible process is given by:

- ,

where the temperature is defined as:

- .

Suppose that the system has

some external parameter, x, that can be changed. In general, the energy

eigenstates of the system will depend on x. According to the adiabatic theorem

of quantum mechanics, in the limit of an infinitely slow change of the

system's Hamiltonian, the system will stay in the same energy eigenstate

and thus change its energy according to the change in energy of the

energy eigenstate it is in.

The generalized force, X, corresponding to the external variable x is defined such that

is the work performed by the system if x is increased by an amount dx.

E.g., if x is the volume, then X is the pressure. The generalized force

for a system known to be in energy eigenstate is given by:

- .

Since the system can be in any energy eigenstate within an interval of , we define the generalized force for the system as the expectation value of the above expression:

- .

To evaluate the average, we partition the energy eigenstates by counting how many of them have a value for within a range between and . Calling this number , we have:

- .

The average defining the generalized force can now be written:

- .

We can relate this to the derivative of the entropy with respect to x

at constant energy E as follows. Suppose we change x to x + dx. Then will change because the energy eigenstates depend on x, causing energy eigenstates to move into or out of the range between and . Let's focus again on the energy eigenstates for which lies within the range between and .

Since these energy eigenstates increase in energy by Y dx, all such

energy eigenstates that are in the interval ranging from E – Y dx to E

move from below E to above E. There are

such energy eigenstates. If , all these energy eigenstates will move into the range between and and contribute to an increase in . The number of energy eigenstates that move from below to above is given by . The difference

is thus the net contribution to the increase in . Note that if Y dx is larger than there will be the energy eigenstates that move from below E to above . They are counted in both and , therefore the above expression is also valid in that case.

Expressing the above expression as a derivative with respect to E and summing over Y yields the expression:

- .

The logarithmic derivative of with respect to x is thus given by:

- .

The first term is intensive, i.e. it does not scale with system size.

In contrast, the last term scales as the inverse system size and will

thus vanishes in the thermodynamic limit. We have thus found that:

- .

Combining this with

gives:

- .

Derivation for systems described by the canonical ensemble

If

a system is in thermal contact with a heat bath at some temperature T

then, in equilibrium, the probability distribution over the energy

eigenvalues are given by the canonical ensemble:

- .

Here Z is a factor that normalizes the sum of all the probabilities to 1, this function is known as the partition function.

We now consider an infinitesimal reversible change in the temperature

and in the external parameters on which the energy levels depend. It

follows from the general formula for the entropy:

- ,

that

- .

Inserting the formula for for the canonical ensemble in here gives:

- .

Living organisms

There

are two principal ways of formulating thermodynamics, (a) through

passages from one state of thermodynamic equilibrium to another, and (b)

through cyclic processes, by which the system is left unchanged, while

the total entropy of the surroundings is increased. These two ways help

to understand the processes of life. This topic is mostly beyond the

scope of this present article, but has been considered by several

authors, such as Erwin Schrödinger, Léon Brillouin and Isaac Asimov. It is also the topic of current research.

To a fair approximation, living organisms may be considered as

examples of (b). Approximately, an animal's physical state cycles by the

day, leaving the animal nearly unchanged. Animals take in food, water,

and oxygen, and, as a result of metabolism, give out breakdown products and heat. Plants take in radiative energy

from the sun, which may be regarded as heat, and carbon dioxide and

water. They give out oxygen. In this way they grow. Eventually they die,

and their remains rot away, turning mostly back into carbon dioxide and

water. This can be regarded as a cyclic process. Overall, the sunlight

is from a high temperature source, the sun, and its energy is passed to a

lower temperature sink, i.e. radiated into space. This is an increase

of entropy of the surroundings of the plant. Thus animals and plants

obey the second law of thermodynamics, considered in terms of cyclic

processes. Simple concepts of efficiency of heat engines are hardly

applicable to this problem because they assume closed systems.

From the thermodynamic viewpoint that considers (a), passages

from one equilibrium state to another, only a roughly approximate

picture appears, because living organisms are never in states of

thermodynamic equilibrium. Living organisms must often be considered as

open systems, because they take in nutrients and give out waste

products. Thermodynamics of open systems is currently often considered

in terms of passages from one state of thermodynamic equilibrium to

another, or in terms of flows in the approximation of local

thermodynamic equilibrium. The problem for living organisms may be

further simplified by the approximation of assuming a steady state with

unchanging flows. General principles of entropy production for such

approximations are subject to unsettled current debate or research. Nevertheless, ideas derived from this viewpoint on the second law of thermodynamics are enlightening about living creatures.

Gravitational systems

In systems that do not require for their descriptions the general theory of relativity, bodies always have positive heat capacity,

meaning that the temperature rises with energy. Therefore, when energy

flows from a high-temperature object to a low-temperature object, the

source temperature is decreased while the sink temperature is increased;

hence temperature differences tend to diminish over time. This is not

always the case for systems in which the gravitational force is

important and the general theory of relativity is required. Such systems

can spontaneously change towards uneven spread of mass and energy. This

applies to the universe in large scale, and consequently it may be

difficult or impossible to apply the second law to it.

Beyond this, the thermodynamics of systems described by the general

theory of relativity is beyond the scope of the present article.

Non-equilibrium states

The theory of classical or equilibrium thermodynamics

is idealized. A main postulate or assumption, often not even explicitly

stated, is the existence of systems in their own internal states of

thermodynamic equilibrium. In general, a region of space containing a

physical system at a given time, that may be found in nature, is not in

thermodynamic equilibrium, read in the most stringent terms. In looser

terms, nothing in the entire universe is or has ever been truly in exact

thermodynamic equilibrium.

For purposes of physical analysis, it is often enough convenient to make an assumption of thermodynamic equilibrium.

Such an assumption may rely on trial and error for its justification.

If the assumption is justified, it can often be very valuable and useful

because it makes available the theory of thermodynamics. Elements of

the equilibrium assumption are that a system is observed to be

unchanging over an indefinitely long time, and that there are so many

particles in a system, that its particulate nature can be entirely

ignored. Under such an equilibrium assumption, in general, there are no

macroscopically detectable fluctuations. There is an exception, the case of critical states, which exhibit to the naked eye the phenomenon of critical opalescence. For laboratory studies of critical states, exceptionally long observation times are needed.

In all cases, the assumption of thermodynamic equilibrium, once made, implies as a consequence that no putative candidate "fluctuation" alters the entropy of the system.

It can easily happen that a physical system exhibits internal

macroscopic changes that are fast enough to invalidate the assumption of

the constancy of the entropy. Or that a physical system has so few

particles that the particulate nature is manifest in observable

fluctuations. Then the assumption of thermodynamic equilibrium is to be

abandoned. There is no unqualified general definition of entropy for

non-equilibrium states.

There are intermediate cases, in which the assumption of local thermodynamic equilibrium is a very good approximation,

but strictly speaking it is still an approximation, not theoretically

ideal. For non-equilibrium situations in general, it may be useful to

consider statistical mechanical definitions of other quantities that may

be conveniently called 'entropy', but they should not be confused or

conflated with thermodynamic entropy properly defined for the second

law. These other quantities indeed belong to statistical mechanics, not

to thermodynamics, the primary realm of the second law.

Even though the applicability of the second law of thermodynamics

is limited for non-equilibrium systems, the laws governing such systems

are still being discussed. One of the guiding principles for systems

which are far from equilibrium is the maximum entropy production

principle.

It states that a system away from equilibrium evolves in such a way as

to maximize entropy production, given present constraints.

The physics of macroscopically observable fluctuations is beyond the scope of this article.

Arrow of time

The second law of thermodynamics is a physical law that is not

symmetric to reversal of the time direction. This does not conflict with

notions that have been observed of the fundamental laws of physics,

namely CPT symmetry, since the second law applies statistically, it is hypothesized, on time-asymmetric boundary conditions.

The second law has been proposed to supply a partial explanation

of the difference between moving forward and backwards in time, such as

why the cause precedes the effect.

Irreversibility

Irreversibility in thermodynamic processes

is a consequence of the asymmetric character of thermodynamic

operations, and not of any internally irreversible microscopic

properties of the bodies. Thermodynamic operations are macroscopic

external interventions imposed on the participating bodies, not derived

from their internal properties. There are reputed "paradoxes" that arise

from failure to recognize this.

Loschmidt's paradox

Loschmidt's paradox,

also known as the reversibility paradox, is the objection that it

should not be possible to deduce an irreversible process from the

time-symmetric dynamics that describe the microscopic evolution of a

macroscopic system.

In the opinion of Schrödinger,

"It is now quite obvious in what manner you have to reformulate the law

of entropy – or for that matter, all other irreversible statements – so

that they be capable of being derived from reversible models. You must

not speak of one isolated system but at least of two, which you may for

the moment consider isolated from the rest of the world, but not always

from each other."

The two systems are isolated from each other by the wall, until it is

removed by the thermodynamic operation, as envisaged by the law. The

thermodynamic operation is externally imposed, not subject to the

reversible microscopic dynamical laws that govern the constituents of

the systems. It is the cause of the irreversibility. The statement of

the law in this present article complies with Schrödinger's advice. The

cause–effect relation is logically prior to the second law, not derived

from it.

Poincaré recurrence theorem

The Poincaré recurrence theorem

considers a theoretical microscopic description of an isolated physical

system. This may be considered as a model of a thermodynamic system

after a thermodynamic operation has removed an internal wall. The system

will, after a sufficiently long time, return to a microscopically

defined state very close to the initial one. The Poincaré recurrence

time is the length of time elapsed until the return. It is exceedingly

long, likely longer than the life of the universe, and depends

sensitively on the geometry of the wall that was removed by the

thermodynamic operation. The recurrence theorem may be perceived as

apparently contradicting the second law of thermodynamics. More

obviously, however, it is simply a microscopic model of thermodynamic

equilibrium in an isolated system formed by removal of a wall between

two systems. For a typical thermodynamical system, the recurrence time

is so large (many many times longer than the lifetime of the universe)

that, for all practical purposes, one cannot observe the recurrence. One

might wish, nevertheless, to imagine that one could wait for the

Poincaré recurrence, and then re-insert the wall that was removed by the

thermodynamic operation. It is then evident that the appearance of

irreversibility is due to the utter unpredictability of the Poincaré

recurrence given only that the initial state was one of thermodynamic

equilibrium, as is the case in macroscopic thermodynamics. Even if one

could wait for it, one has no practical possibility of picking the right

instant at which to re-insert the wall. The Poincaré recurrence theorem

provides a solution to Loschmidt's paradox. If an isolated

thermodynamic system could be monitored over increasingly many multiples

of the average Poincaré recurrence time, the thermodynamic behavior of

the system would become invariant under time reversal.

James Clerk Maxwell

Maxwell's demon

James Clerk Maxwell imagined one container divided into two parts, A and B. Both parts are filled with the same gas at equal temperatures and placed next to each other, separated by a wall. Observing the molecules on both sides, an imaginary demon guards a microscopic trapdoor in the wall. When a faster-than-average molecule from A flies towards the trapdoor, the demon opens it, and the molecule will fly from A to B. The average speed of the molecules in B will have increased while in A they will have slowed down on average. Since average molecular speed corresponds to temperature, the temperature decreases in A and increases in B, contrary to the second law of thermodynamics.

One response to this question was suggested in 1929 by Leó Szilárd and later by Léon Brillouin.

Szilárd pointed out that a real-life Maxwell's demon would need to have

some means of measuring molecular speed, and that the act of acquiring

information would require an expenditure of energy.

Maxwell's 'demon' repeatedly alters the permeability of the wall between A and B. It is therefore performing thermodynamic operations on a microscopic scale, not just observing ordinary spontaneous or natural macroscopic thermodynamic processes.

Quotations

The law that entropy always increases holds, I think, the supreme position among the laws of Nature. If someone points out to you that your pet theory of the universe is in disagreement with Maxwell's equations – then so much the worse for Maxwell's equations. If it is found to be contradicted by observation – well, these experimentalists do bungle things sometimes. But if your theory is found to be against the second law of thermodynamics I can give you no hope; there is nothing for it but to collapse in deepest humiliation.

— Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington, The Nature of the Physical World (1927)

There have been nearly as many formulations of the second law as there have been discussions of it.

— Philosopher / Physicist P.W. Bridgman, (1941)

Clausius is the author of the sibyllic utterance, "The energy of the universe is constant; the entropy of the universe tends to a maximum." The objectives of continuum thermomechanics stop far short of explaining the "universe", but within that theory we may easily derive an explicit statement in some ways reminiscent of Clausius, but referring only to a modest object: an isolated body of finite size.— Truesdell, C., Muncaster, R.G. (1980). Fundamentals of Maxwell's Kinetic Theory of a Simple Monatomic Gas, Treated as a Branch of Rational Mechanics, Academic Press, New York, ISBN 0-12-701350-4, p. 17.

,

,

,

,

.

.

.

. .

. ,

,

.

. ,

, ,

, .

. .

. .

. ,

,

.

. ,

,

,

, ,

,

,

,

![S = k_{\mathrm B} \ln\left[\Omega\left(E\right)\right]\,](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bb924dffe4f5c2c580cd40461cf5bfc5159ac881) ,

,

,

,![\frac{1}{k_{\mathrm B} T}\equiv\beta\equiv\frac{d\ln\left[\Omega\left(E\right)\right]}{dE}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e720432da60639a2f9cdcefb4ac56845da4f36b0) .

.

.

. .

.

.

. .

.

.

. .

.

.

. ,

, .

.