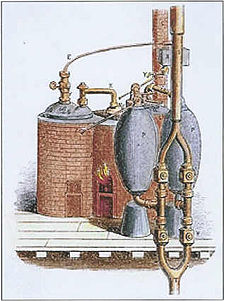

The 1698 Savery Engine – the world's first commercially useful steam engine: built by Thomas Savery

The history of thermodynamics is a fundamental strand in the history of physics, the history of chemistry, and the history of science in general. Owing to the relevance of thermodynamics in much of science and technology, its history is finely woven with the developments of classical mechanics, quantum mechanics, magnetism, and chemical kinetics, to more distant applied fields such as meteorology, information theory, and biology (physiology), and to technological developments such as the steam engine, internal combustion engine, cryogenics and electricity generation. The development of thermodynamics both drove and was driven by atomic theory. It also, albeit in a subtle manner, motivated new directions in probability and statistics.

History

Contributions from antiquity

The ancients viewed heat as that related to fire. In 3000 BC, the ancient Egyptians viewed heat as related to origin mythologies.

In the Western philosophical tradition, after much debate about the primal element among earlier pre-Socratic philosophers, Empedocles proposed a four-element theory, in which all substances derive from earth, water, air, and fire. The Empedoclean element of fire is perhaps the principal ancestor of later concepts such as phlogin and caloric. Around 500 BC, the Greek philosopher Heraclitus

became famous as the "flux and fire" philosopher for his proverbial

utterance: "All things are flowing." Heraclitus argued that the three principal elements in nature were fire, earth, and water.

Heating a body, such as a segment of protein alpha helix (above), tends to cause its atoms to vibrate more, and to expand or change phase, if heating is continued; an axiom of nature noted by Herman Boerhaave in the 1700s.

Atomism is a central part of today's relationship between thermodynamics and statistical mechanics. Ancient thinkers such as Leucippus and Democritus, and later the Epicureans, by advancing atomism, laid the foundations for the later atomic theory. Until experimental proof of atoms

was later provided in the 20th century, the atomic theory was driven

largely by philosophical considerations and scientific intuition.

The 5th century BC, Greek philosopher Parmenides, in his only known work, a poem conventionally titled On Nature, uses verbal reasoning to postulate that a void, essentially what is now known as a vacuum, in nature could not occur. This view was supported by the arguments of Aristotle, but was criticized by Leucippus and Hero of Alexandria.

From antiquity to the Middle Ages various arguments were put forward

to prove or disapprove the existence of a vacuum and several attempts

were made to construct a vacuum but all proved unsuccessful.

The European scientists Cornelius Drebbel, Robert Fludd, Galileo Galilei and Santorio Santorio in the 16th and 17th centuries were able to gauge the relative "coldness" or "hotness" of air, using a rudimentary air thermometer (or thermoscope). This may have been influenced by an earlier device which could expand and contract the air constructed by Philo of Byzantium and Hero of Alexandria.

Around 1600, the English philosopher and scientist Francis Bacon surmised: "Heat itself, its essence and quiddity is motion and nothing else." In 1643, Galileo Galilei, while generally accepting the 'sucking' explanation of horror vacui

proposed by Aristotle, believed that nature's vacuum-abhorrence is

limited. Pumps operating in mines had already proven that nature would

only fill a vacuum with water up to a height of ~30 feet. Knowing this

curious fact, Galileo encouraged his former pupil Evangelista Torricelli to investigate these supposed limitations. Torricelli did not believe that vacuum-abhorrence (Horror vacui)

in the sense of Aristotle's 'sucking' perspective, was responsible for

raising the water. Rather, he reasoned, it was the result of the

pressure exerted on the liquid by the surrounding air.

To prove this theory, he filled a long glass tube (sealed at one

end) with mercury and upended it into a dish also containing mercury.

Only a portion of the tube emptied (as shown adjacent); ~30 inches of

the liquid remained. As the mercury emptied, and a partial vacuum was created at the top of the tube. The gravitational force on the heavy element Mercury prevented it from filling the vacuum.

Transition from chemistry to thermochemistry

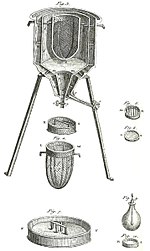

The world's first ice-calorimeter, used in the winter of 1782-83, by Antoine Lavoisier and Pierre-Simon Laplace, to determine the heat evolved in various chemical changes; calculations which were based on Joseph Black's prior discovery of latent heat. These experiments mark the foundation of thermochemistry.

The theory of phlogiston arose in the 17th century, late in the period of alchemy. Its replacement by caloric theory

in the 18th century is one of the historical markers of the transition

from alchemy to chemistry. Phlogiston was a hypothetical substance that

was presumed to be liberated from combustible substances during burning, and from metals during the process of rusting.

Caloric, like phlogiston, was also presumed to be the "substance" of

heat that would flow from a hotter body to a cooler body, thus warming

it.

The first substantial experimental challenges to caloric theory arose in Rumford's 1798 work, when he showed that boring cast iron cannons produced great amounts of heat which he ascribed to friction, and his work was among the first to undermine the caloric theory. The development of the steam engine also focused attention on calorimetry and the amount of heat produced from different types of coal. The first quantitative research on the heat changes during chemical reactions was initiated by Lavoisier using an ice calorimeter following research by Joseph Black on the latent heat of water.

More quantitative studies by James Prescott Joule in 1843 onwards provided soundly reproducible phenomena, and helped to place the subject of thermodynamics on a solid footing. William Thomson,

for example, was still trying to explain Joule's observations within a

caloric framework as late as 1850. The utility and explanatory power of kinetic theory, however, soon started to displace caloric and it was largely obsolete by the end of the 19th century. Joseph Black and Lavoisier made important contributions in the precise measurement of heat changes using the calorimeter, a subject which became known as thermochemistry.

Phenomenological thermodynamics

Robert Boyle. 1627-1691

- Boyle's law (1662)

- Charles's law was first published by Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac in 1802, but he referenced unpublished work by Jacques Charles from around 1787. The relationship had been anticipated by the work of Guillaume Amontons in 1702.

- Gay-Lussac's law (1802)

Birth of thermodynamics as a science

Irish physicist and chemist Robert Boyle in 1656, in coordination with English scientist Robert Hooke,

built an air pump. Using this pump, Boyle and Hooke noticed the

pressure-volume correlation: P.V=constant. In that time, air was assumed

to be a system of motionless particles, and not interpreted as a system

of moving molecules. The concept of thermal motion came two centuries

later. Therefore, Boyle's publication in 1660 speaks about a mechanical

concept: the air spring. Later, after the invention of the thermometer, the property temperature could be quantified. This tool gave Gay-Lussac the opportunity to derive his law, which led shortly later to the ideal gas law. But, already before the establishment of the ideal gas law, an associate of Boyle's named Denis Papin

built in 1679 a bone digester, which is a closed vessel with a tightly

fitting lid that confines steam until a high pressure is generated.

Later designs implemented a steam release valve to keep the

machine from exploding. By watching the valve rhythmically move up and

down, Papin conceived of the idea of a piston and cylinder engine. He

did not however follow through with his design. Nevertheless, in 1697,

based on Papin's designs, engineer Thomas Savery

built the first engine. Although these early engines were crude and

inefficient, they attracted the attention of the leading scientists of

the time. One such scientist was Sadi Carnot, the "father of thermodynamics", who in 1824 published Reflections on the Motive Power of Fire, a discourse on heat, power, and engine efficiency. This marks the start of thermodynamics as a modern science.

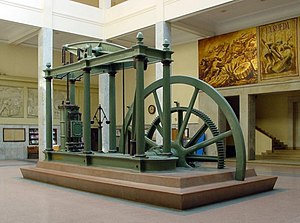

A Watt steam engine, the steam engine that propelled the Industrial Revolution in Britain and the world

Hence, prior to 1698 and the invention of the Savery Engine,

horses were used to power pulleys, attached to buckets, which lifted

water out of flooded salt mines in England. In the years to follow, more

variations of steam engines were built, such as the Newcomen Engine, and later the Watt Engine.

In time, these early engines would eventually be utilized in place of

horses. Thus, each engine began to be associated with a certain amount

of "horse power" depending upon how many horses it had replaced. The

main problem with these first engines was that they were slow and

clumsy, converting less than 2% of the input fuel

into useful work. In other words, large quantities of coal (or wood)

had to be burned to yield only a small fraction of work output. Hence

the need for a new science of engine dynamics was born.

Sadi Carnot (1796-1832): the "father" of thermodynamics

Most cite Sadi Carnot's 1824 book Reflections on the Motive Power of Fire as the starting point for thermodynamics as a modern science. Carnot defined "motive power" to be the expression of the useful effect that a motor is capable of producing. Herein, Carnot introduced us to the first modern day definition of "work": weight lifted through a height. The desire to understand, via formulation, this useful effect in relation to "work" is at the core of all modern day thermodynamics.

In 1843, James Joule experimentally found the mechanical equivalent of heat.

In 1845, Joule reported his best-known experiment, involving the use of

a falling weight to spin a paddle-wheel in a barrel of water, which

allowed him to estimate a mechanical equivalent of heat of

819 ft·lbf/Btu (4.41 J/cal). This led to the theory of conservation of energy and explained why heat can do work.

In 1850, the famed mathematical physicist Rudolf Clausius coined the term "entropy" (das Wärmegewicht, symbolized S) to denote heat lost or turned into waste. ("Wärmegewicht" translates literally as "heat-weight"; the corresponding English term stems from the Greek τρέπω, "I turn".)

The name "thermodynamics", however, did not arrive until 1854, when the British mathematician and physicist William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) coined the term thermo-dynamics in his paper On the Dynamical Theory of Heat.

In association with Clausius, in 1871, the Scottish mathematician and physicist James Clerk Maxwell formulated a new branch of thermodynamics called Statistical Thermodynamics, which functions to analyze large numbers of particles at equilibrium, i.e., systems where no changes are occurring, such that only their average properties as temperature T, pressure P, and volume V become important.

Soon thereafter, in 1875, the Austrian physicist Ludwig Boltzmann formulated a precise connection between entropy S and molecular motion:

being defined in terms of the number of possible states [W] such motion could occupy, where k is the Boltzmann's constant.

The following year, 1876, chemical engineer Willard Gibbs published an obscure 300-page paper titled: On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances, wherein he formulated one grand equality, the Gibbs free energy

equation, which suggested a measure of the amount of "useful work"

attainable in reacting systems. Gibbs also originated the concept we

now know as enthalpy H, calling it "a heat function for constant pressure".

The modern word enthalpy would be coined many years later by Heike Kamerlingh Onnes,

who based it on the Greek word enthalpein meaning to warm.

Building on these foundations, those as Lars Onsager, Erwin Schrödinger, and Ilya Prigogine, and others, functioned to bring these engine "concepts" into the thoroughfare of almost every modern-day branch of science.

Kinetic theory

The idea that heat is a form of motion is perhaps an ancient one and is certainly discussed by Francis Bacon in 1620 in his Novum Organum. The first written scientific reflection on the microscopic nature of heat is probably to be found in a work by Mikhail Lomonosov, in which he wrote:

- (..) movement should not be denied based on the fact it is not seen. Who would deny that the leaves of trees move when rustled by a wind, despite it being unobservable from large distances? Just as in this case motion remains hidden due to perspective, it remains hidden in warm bodies due to the extremely small sizes of the moving particles. In both cases, the viewing angle is so small that neither the object nor their movement can be seen.

During the same years, Daniel Bernoulli published his book Hydrodynamics

(1738), in which he derived an equation for the pressure of a gas

considering the collisions of its atoms with the walls of a container.

He proves that this pressure is two thirds the average kinetic energy of

the gas in a unit volume. Bernoulli's ideas, however, made little impact on the dominant caloric culture. Bernoulli made a connection with Gottfried Leibniz's vis viva principle, an early formulation of the principle of conservation of energy,

and the two theories became intimately entwined throughout their

history. Though Benjamin Thompson suggested that heat was a form of

motion as a result of his experiments in 1798, no attempt was made to

reconcile theoretical and experimental approaches, and it is unlikely

that he was thinking of the vis viva principle.

John Herapath later independently formulated a kinetic theory in 1820, but mistakenly associated temperature with momentum rather than vis viva or kinetic energy. His work ultimately failed peer review and was neglected. John James Waterston

in 1843 provided a largely accurate account, again independently, but

his work received the same reception, failing peer review even from

someone as well-disposed to the kinetic principle as Davy.

Further progress in kinetic theory started only in the middle of the 19th century, with the works of Rudolf Clausius, James Clerk Maxwell, and Ludwig Boltzmann. In his 1857 work On the nature of the motion called heat,

Clausius for the first time clearly states that heat is the average

kinetic energy of molecules. This interested Maxwell, who in 1859

derived the momentum distribution later named after him. Boltzmann

subsequently generalized his distribution for the case of gases in

external fields.

Boltzmann is perhaps the most significant contributor to kinetic

theory, as he introduced many of the fundamental concepts in the theory.

Besides the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution mentioned above, he also associated the kinetic energy of particles with their degrees of freedom. The Boltzmann equation

for the distribution function of a gas in non-equilibrium states is

still the most effective equation for studying transport phenomena in

gases and metals. By introducing the concept of thermodynamic probability as the number of microstates corresponding to the current macrostate, he showed that its logarithm is proportional to entropy.

Branches of thermodynamics

The following list gives a rough outline as to when the major branches of thermodynamics came into inception:

- Thermochemistry - 1780s

- Classical thermodynamics - 1824

- Chemical thermodynamics - 1876

- Statistical mechanics - c. 1880s

- Equilibrium thermodynamics

- Engineering thermodynamics

- Chemical engineering thermodynamics - c. 1940s

- Non-equilibrium thermodynamics - 1941

- Small systems thermodynamics - 1960s

- Biological thermodynamics - 1957

- Ecosystem thermodynamics - 1959

- Relativistic thermodynamics - 1965

- Rational thermodynamics - 1960s

- Quantum thermodynamics - 1968

- Black hole thermodynamics - c. 1970s

- Geological thermodynamics - c. 1970s

- Biological evolution thermodynamics - 1978

- Geochemical thermodynamics - c. 1980s

- Atmospheric thermodynamics - c. 1980s

- Natural systems thermodynamics - 1990s

- Supramolecular thermodynamics - 1990s

- Earthquake thermodynamics - 2000

- Drug-receptor thermodynamics - 2001

- Pharmaceutical systems thermodynamics – 2002

Ideas from thermodynamics have also been applied in other fields, for example:

- Thermoeconomics - c. 1970s

Entropy and the second law

Even though he was working with the caloric theory, Sadi Carnot

in 1824 suggested that some of the caloric available for generating

useful work is lost in any real process. In March 1851, while grappling

to come to terms with the work of James Prescott Joule, Lord Kelvin

started to speculate that there was an inevitable loss of useful heat

in all processes. The idea was framed even more dramatically by Hermann von Helmholtz in 1854, giving birth to the spectre of the heat death of the universe.

In 1854, William John Macquorn Rankine started to make use in calculation of what he called his thermodynamic function. This has subsequently been shown to be identical to the concept of entropy formulated by Rudolf Clausius in 1865. Clausius used the concept to develop his classic statement of the second law of thermodynamics the same year.

Heat transfer

The phenomenon of heat conduction is immediately grasped in everyday life. In 1701, Sir Isaac Newton published his law of cooling.

However, in the 17th century, it came to be believed that all materials

had an identical conductivity and that differences in sensation arose

from their different heat capacities.

Suggestions that this might not be the case came from the new science of electricity in which it was easily apparent that some materials were good electrical conductors while others were effective insulators. Jan Ingen-Housz in 1785-9 made some of the earliest measurements, as did Benjamin Thompson during the same period.

The fact that warm air rises and the importance of the phenomenon to meteorology was first realised by Edmund Halley in 1686. Sir John Leslie observed that the cooling effect of a stream of air increased with its speed, in 1804.

Carl Wilhelm Scheele distinguished heat transfer by thermal radiation (radiant heat) from that by convection and conduction in 1777. In 1791, Pierre Prévost

showed that all bodies radiate heat, no matter how hot or cold they

are. In 1804, Leslie observed that a matte black surface radiates heat

more effectively than a polished surface, suggesting the importance of black body radiation. Though it had become to be suspected even from Scheele's work, in 1831 Macedonio Melloni demonstrated that black body radiation could be reflected, refracted and polarised in the same way as light.

James Clerk Maxwell's 1862 insight that both light and radiant heat were forms of electromagnetic wave led to the start of the quantitative analysis of thermal radiation. In 1879, Jožef Stefan observed that the total radiant flux from a blackbody is proportional to the fourth power of its temperature and stated the Stefan–Boltzmann law. The law was derived theoretically by Ludwig Boltzmann in 1884.

Absolute Zero

In 1702 Guillaume Amontons introduced the concept of absolute zero based on observations of gases.

In 1810, Sir John Leslie froze water to ice artificially. The idea of

absolute zero was generalized in 1848 by Lord Kelvin. In 1906, Walther Nernst stated the third law of thermodynamics.