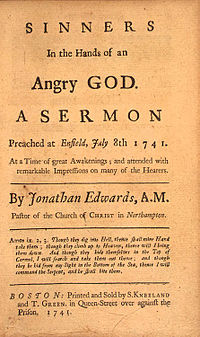

Edwards, Rev. Jonathan (July 8, 1741), Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God, A Sermon Preached at Enfield

The First Great Awakening (sometimes Great Awakening) or the Evangelical Revival was a series of Christian revivals that swept Britain and its Thirteen Colonies between the 1730s and 1740s. The revival movement permanently affected Protestantism as adherents strove to renew individual piety and religious devotion. The Great Awakening marked the emergence of Anglo-American evangelicalism as a transdenominational movement within the Protestant churches. In the United States, the term Great Awakening is most often used, while in the United Kingdom, it is referred to as the Evangelical Revival.

Building on the foundations of older traditions—Puritanism, pietism and Presbyterianism—major leaders of the revival such as George Whitefield, John Wesley and Jonathan Edwards articulated a theology of revival and salvation

that transcended denominational boundaries and helped create a common

evangelical identity. Revivalists added to the doctrinal imperatives of Reformation Protestantism an emphasis on providential outpourings of the Holy Spirit. Extemporaneous preaching gave listeners a sense of deep personal conviction of their need of salvation by Jesus Christ

and fostered introspection and commitment to a new standard of personal

morality. Revival theology stressed that religious conversion was not

only intellectual assent to correct Christian doctrine but had to be a "new birth" experienced in the heart. Revivalists also taught that receiving assurance of salvation was a normal expectation in the Christian life.

While the Evangelical Revival united evangelicals across various

denominations around shared beliefs, it also led to division in existing

churches between those who supported the revivals and those who did

not. Opponents accused the revivals of fostering disorder and fanaticism

within the churches by enabling uneducated, itinerant preachers and encouraging religious enthusiasm. In England, evangelical Anglicans would grow into an important constituency within the Church of England, and Methodism would develop out of the ministries of Whitefield and Wesley. In the American colonies, the Awakening caused the Congregational and Presbyterian churches to split, while it strengthened both the Methodist and Baptist denominations. It had little impact on most Lutherans, Quakers, and non-Protestants.

Evangelical preachers "sought to include every person in conversion, regardless of gender, race, and status." Throughout the colonies, especially in the South, the revival movement increased the number of African slaves and free blacks who were exposed to and subsequently converted to Christianity. It also inspired the creation of new missionary societies, such as the Baptist Missionary Society in 1792.

Events in continental Europe

Historian Sydney E. Ahlstrom sees the Great Awakening as part of a "great international Protestant upheaval" that also created pietism in the Lutheran and Reformed churches of continental Europe. Pietism emphasized heartfelt religious faith in reaction to an overly intellectual Protestant scholasticism

perceived as spiritually dry. Significantly, the pietists placed less

emphasis on traditional doctrinal divisions between Protestant churches,

focusing rather on religious experience and affections.

Pietism prepared Europe for revival, and it usually occurred in

areas where pietism was strong. The most important leader of the

Awakening in central Europe was Nicolaus Zinzendorf, a Saxon noble who studied under pietist leader August Hermann Francke at Halle University. In 1722, Zinzendorf invited members of the Moravian Church to live and worship on his estates, establishing a community at Herrnhut.

The Moravians came to Herrnhut as refugees, but under Zinzendorf's

guidance, the group enjoyed a religious revival. Soon, the community

became a refuge for other Protestants as well, including German

Lutherans, Reformed Christians and Anabaptists. The church began to

grow, and Moravian societies would be established in England where they

would help foster the Evangelical Revival as well.

Events in Britain

While known as the Great Awakening in the United States, the movement is referred to as the Evangelical Revival in Britain. The revivalist tradition had existed in Scottish Presbyterianism since the 1620s. The Evangelical Revival, however, first broke out in Wales. In 1735, Howell Harris and Daniel Rowland experienced a religious conversion and began preaching to large crowds throughout South Wales. Their preaching initiated the Welsh Methodist revival.

In England, the major leaders of the Evangelical Revival were brothers John and Charles Wesley and their friend George Whitefield, who would become the founders of Methodism. They had been members of a religious society at Oxford University called the Holy Club and "Methodists" due to their methodical piety. This society was modeled on the collegia pietatis (cell groups) used by pietists for Bible study, prayer and accountability. All three men experienced a spiritual crisis in which they sought true conversion and assurance of faith.

Whitefield joined the Holy Club in 1733 and, under the influence of Charles Wesley, read German pietist August Hermann Francke's Against the Fear of Man and Scottish theologian Henry Scougal's The Life of God in the Soul of Man.

Whitefield wrote that he "never knew what true religion was" until he

read Scougal, who said that it consisted of becoming a "new creature".

From that point on, Whitefield sought the new birth. After a period of

spiritual struggle, Whitefield experienced conversion during Lent in 1735. Afterwards, he was ordained a priest in the Church of England,

but he always maintained a willingness to work with evangelicals from

other denominations. In 1737, Whitefield began preaching in Bristol and

London, and he became well known for his dramatic sermons, which were

reported on by the press.

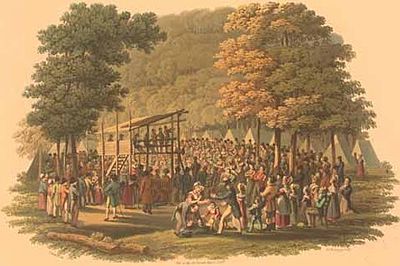

In February 1739, Whitefield began open-air field preaching in the mining community of Kingswood,

near Bristol. He learned this method from Howell Harris, who had been

successfully field preaching in Wales. Within a week, he was preaching

to crowds of 10,000. By May, he was preaching in London to crowds of

50,000. While enjoying success, his itinerant preaching was controversial. Many Anglican

pulpits were closed to him, and he had to struggle against Anglicans

who opposed the Methodists and the "doctrine of the New Birth".

Whitefield wrote of his opponents, "I am fully convinced there is a

fundamental difference between us and them. They believe only an outward

Christ, we further believe that He must be inwardly formed in our

hearts also. But the natural man receiveth not the things of the Spirit

of God." In August 1739, Whitefield left England to begin his preaching

tour in the American colonies.

In 1736, John Wesley was returning to England from a failed

Anglican mission in Georgia when he came into contact with members of

the Moravian Church led by August Gottlieb Spangenberg.

The Moravians' faith and piety deeply impressed Wesley, especially

their belief that it was a normal part of Christian life to have an

assurance of one's salvation.

Despite being an Anglican priest, his encounters with the Moravians led

him to conclude that he was in need of conversion himself. He developed

further contacts with the Moravians in London and became friends with

Moravian minister Peter Boehler who convinced him to join a Moravian small group called the Fetter Lane Society.

In May 1738, Wesley attended a Moravian meeting on Aldersgate

Street in London where he felt spiritually transformed during a reading

of Martin Luther's preface to the Epistle to the Romans.

Wesley recounted that "I felt my heart strangely warmed. I felt I did

trust in Christ, Christ alone for salvation, and an assurance was given

me that he had taken away my sins, even mine, and saved me from the law of sin and death."

Wesley understood his "Aldersgate experience" to be an evangelical

conversion, and it provided him with the assurance of his salvation that

he had been seeking. Afterwards, he traveled to Herrnhut and met

Zinzendorf in person.

By March 1739, Whitefield was ready to launch his preaching tour

in the 13 Colonies but wanted someone to continue the revival preaching

at Bristol. He turned to Wesley who was at first uneasy about preaching

outdoors, which violated his high-church

sense of decency. Eventually, however, Wesley changed his mind and, in

his own words, "submitted to be more vile, and proclaimed in the

highways the glad tidings of salvation". On April 2, 1739, Wesley

preached to about 3,000 people near Bristol.

Scotland

The origins of revivalism in Scotland stretch back to the 1620s. The attempts by the Stuart Kings to impose bishops on the Church of Scotland led to national protests in the form of the Covenanters. In addition, radical Presbyterian clergy held outdoor conventicles throughout southern and western Scotland centering on the communion season. These revivals would also spread to Ulster and featured "marathon extemporaneous preaching and excessive popular enthusiasm."

In the 18th century, the Evangelical Revival was led by ministers such as Ebenezer Erskine, William M'Culloch (the minister who presided over the Cambuslang Work of 1742), and James Robe (minister at Kilsyth). A substantial number of Church of Scotland ministers held evangelical views.

Events in America

Early revivals

In the early 18th century, the 13 Colonies were religiously diverse. In New England, the Congregational churches were the established religion; whereas in the religiously tolerant Middle Colonies, the Quakers, Dutch Reformed, Anglican, Presbyterian, Lutheran, Congregational, and Baptist churches all competed with each other on equal terms. In the Southern colonies, the Anglican church was officially established, though there were significant numbers of Baptists, Quakers and Presbyterians. At the same time, church membership was low from having failed to keep up with population growth, and the influence of Enlightenment rationalism was leading many people to turn to atheism, Deism, Unitarianism and Universalism.

The churches in New England had fallen into a "staid and routine

formalism in which experiential faith had been a reality to only a

scattered few."

In response to these trends, ministers influenced by New England Puritanism, Scots-Irish Presbyterianism, and European Pietism began calling for a revival of religion and piety. The blending of these three traditions would produce an evangelical Protestantism that placed greater importance "on seasons of revival, or outpourings of the Holy Spirit, and on converted sinners experiencing God's love personally." In the 1710s and 1720s, revivals became more frequent among New England Congregationalists. These early revivals, however, remained local affairs due to the lack of coverage in print media.

The first revival to receive widespread publicity was that precipitated

by an earthquake in 1727. As they began to be publicized more widely,

revivals transformed from merely local to regional and transatlantic

events.

In the 1720s and 1730s, an evangelical party took shape in the Presbyterian churches of the Middle Colonies led by William Tennent, Sr., of Neshaminy, Pennsylvania. He established a seminary called the Log College where he trained nearly 20 Presbyterian revivalists for the ministry, including his three sons and Samuel Blair. Within the Synod of Philadelphia, these ministers would gravitate towards the anti-subscriptionist party led by Jonathan Dickinson. This faction opposed requiring ministers to subscribe to the Westminster Confession of Faith,

believing that the Bible itself was a sufficient rule of faith and

practice and that the church's purity could best be guaranteed by

closely examining the religious experiences of ordination candidates and disciplining scandalous ministers.

While pastoring a church in New Brunswick, New Jersey, Gilbert Tennent became acquainted with Dutch Reformed minister Theodorus Jacobus Frelinghuysen. Historian Sydney Ahlstrom described Frelinghuysen as "an important herald, if not the father of the Great Awakening".

An advocate of Reformed pietism, Frelinghuysen believed in the

necessity of personal conversion and living a holy life. The revivals he

led in the Raritan Valley were "forerunners" of the Great Awakening in

the Middle Colonies. Under Frelinghuysen's influence, Tennent came to

believe that a definite conversion experience followed by assurance of

salvation was the key mark of a Christian. By 1729, Tennent was seeing

signs of revival in the Presbyterian churches of New Brunswick and

Staten Island. At the same time, Gilbert's brothers, William and John,

oversaw a revival at Freehold, New Jersey.

Northampton revival

Monument in Enfield, Connecticut commemorating the location where Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God was preached

The most influential evangelical revival was the Northampton revival

of 1734–1735 under the leadership of Congregational minister Jonathan Edwards. In the fall of 1734, Edwards preached a sermon series on justification by faith alone, and the community's response was extraordinary. Signs of religious commitment among the laity

increased, especially among the town's young people. Edwards wrote to

Boston minister Benjamin Colman that the town "never was so full of

Love, nor so full of Joy, nor so full of distress as it has lately

been. ... I never saw the Christian spirit in Love to Enemies so

exemplified, in all my Life as I have seen it within this half-year."

The revival ultimately spread to 25 communities in western

Massachusetts and central Connecticut until it began to wane in 1737.

At a time when Enlightenment rationalism and Arminian

theology was popular among some Congregational clergy, Edwards held to

traditional Calvinist doctrine. He understood conversion to be the

experience of moving from spiritual deadness to joy in the knowledge of one's election

(that one had been chosen by God for salvation). While a Christian

might have several conversion moments as part of this process, Edwards

believed there was a single point in time when God regenerated an individual, even if the exact moment could not be pinpointed.

The Northampton revival featured instances of what critics called enthusiasm but what supporters believed were signs of the Holy Spirit. Services became more emotional and some people had visions and mystical

experiences. Edwards cautiously defended these experiences as long as

they led individuals to a greater belief in God's glory rather than in

self-glorification. Similar experiences would appear in most of the

major revivals of the 18th century.

Edwards wrote an account of the Northampton revival, A Faithful Narrative, which was published in England through the efforts of prominent evangelicals John Guyse and Isaac Watts.

The publication of his account made Edwards a celebrity in Britain and

influenced the growing revival movement in that nation. A Faithful Narrative would become a model on which other revivals would be conducted.

Whitefield, Tennent and Davenport

George Whitefield first came to America in 1738 to preach in Georgia and found Bethesda Orphanage. Whitefield returned to the Colonies in November 1739. His first stop was in Philadelphia where he initially preached at Christ Church,

Philadelphia's Anglican church, and then preached to a large outdoor

crowd from the courthouse steps. He then preached in many Presbyterian

churches.

From Philadelphia, Whitefield traveled to New York and then to the

South. In the Middle Colonies, he was popular in the Dutch and German

communities as well as among the British. Lutheran pastor Henry Muhlenberg

told of a German woman who heard Whitefield preach and, though she

spoke no English, later said she had never before been so edified.

As revivalism spread through the Presbyterian churches, the old

disputes between the subscription and anti-subscription parties were

recast into conflict between the anti-revival "Old Side" and pro-revival

"New Side", respectively. At issue was the place of revivalism in

American Presbyterianism, specifically the "relation between doctrinal

orthodoxy and experimental knowledge of Christ."

The New Side, led by Gilbert Tennent and Jonathan Dickinson, believed

that strict adherence to orthodoxy was meaningless if one lacked a

personal religious experience, a sentiment expressed in Tennent's 1739

sermon "The Danger of an Unconverted Ministry". Whitefield's tour had

helped the revival party grow and only worsened the Old Side–New Side Controversy. When the Synod of Philadelphia met in May 1741, the Old Side expelled the New Side, which then reorganized itself into the Synod of New York.

In 1740, Whitefield began touring New England. He landed in Newport, Rhode Island,

on September 14, 1740, and preached several times in the Anglican

church. He then moved on to Boston, Massachusetts, where he spent a

week. There were prayers at King's Chapel (at the time an Anglican church) and preaching at Brattle Street Church and South Church. On September 20, Whitefield preached in First Church

and then outside of it to about 8,000 people who could not gain

entrance. The next day, he preached outdoors again to about 15,000

people. On Tuesday, he preached at Second Church and on Wednesday at Harvard University.

After traveling as far as Portsmouth, New Hampshire, he returned to

Boston on October 12 to preach to 30,000 people before continuing his

tour.

Whitefield then traveled to Northampton at the invitation of

Jonathan Edwards. He preached twice in the parish church while Edwards

was so moved that he wept. He then spent time in New Haven, Connecticut,

where he preached at Yale University. From there he traveled down the

coast, reaching New York on October 29. Whitefield's assessment of New

England's churches and clergy prior to his intervention was negative. "I

am verily persuaded," he wrote, "the Generality of Preachers talk of an

unknown, unfelt Christ. And the Reason why Congregations have been so

dead, is because dead Men preach to them."

Whitefield met Gilbert Tennent on Staten Island and asked him to

preach in Boston to continue the revival there. Tennent accepted and in

December began a three-month long preaching tour throughout New England.

Besides Boston, Tennent preached in towns throughout Massachusetts,

Rhode Island and Connecticut. Like Whitefield's, Tennent's preaching

produced large crowds, many conversions and much controversy. While

antirevivalists such as Timothy Cutler heavily criticized Tennent's preaching, most of Boston's ministers were supportive.

Tennent was followed in the summer of 1741 by itinerant minister James Davenport,

who proved to be more controversial than either Tennent or Whitefield.

His rants and attacks against "unconverted" ministers inspired much

opposition, and he was arrested in Connecticut for violating a law

against itinerant preaching. At his trial, he was found mentally ill and

deported to Long Island. Soon after, he arrived in Boston and resumed

his fanatical preaching only to once again be declared insane and

expelled. The last of Davenport's radical episodes took place in March

1743 in New London when he ordered his followers to burn wigs, cloaks,

rings and other vanities. He also ordered the burning of books by religious authors such as John Flavel and Increase Mather. Following the intervention of two pro-revival "New Light" ministers, Davenport's mental state apparently improved, and he published a retraction of his earlier excesses.

Whitefield, Tennent and Davenport would be followed by a number

of both clerical and lay itinerants. However, the Awakening in New

England was primarily sustained by the efforts of parish ministers. Sometimes revival would be initiated by regular preaching or the customary pulpit

exchanges between two ministers. Through their efforts, New England

experienced a "great and general Awakening" between 1740 and 1743

characterized by a greater interest in religious experience, widespread

emotional preaching, and intense emotional reactions accompanying

conversion, including fainting and weeping.

There was a greater emphasis on prayer and devotional reading, and the

Puritan ideal of a converted church membership was revived. It is

estimated that between 20,000 to 50,000 new members were admitted to New

England's Congregational churches even as expectations for members

increased.

By 1745, the Awakening had begun to wane. Revivals would continue

to spread to the southern back country and slave communities in the

1750s and 1760s.

Old and New Lights

Philadelphia's Second Presbyterian Church, ministered by New Light Gilbert Tennent, was built between 1750 and 1753 after the split between Old and New Side Presbyterians.

The Great Awakening aggravated existing conflicts within the Protestant churches, often leading to schisms between supporters of revival, known as "New Lights", and opponents of revival, known as "Old Lights". Old Lights saw the religious enthusiasm and itinerant preaching

unleashed by the Awakening as disruptive to church order, preferring

formal worship and a settled, university-educated ministry. They mocked

revivalists as being ignorant, heterodox or con artists.

New Lights accused Old Lights of being more concerned with social

status than with saving souls and even questioned whether some Old Light

ministers were even converted. They also supported itinerant ministers

who disregarded parish boundaries.

Congregationalists in New England experienced 98 schisms, which

in Connecticut also affected which group would be considered "official"

for tax purposes. It is estimated in New England that in the churches

there were about one-third each of New Lights, Old Lights, and those who

saw both sides as valid. The Awakening aroused a wave of separatist

feeling within the Congregational churches of New England. Around 100

Separatist congregations were organized throughout the region by Strict Congregationalists. Objecting to the Halfway Covenant, Strict Congregationalists required evidence of conversion for church membership and also objected to the semi–presbyterian Saybrook Platform,

which they felt infringed on congregational autonomy. Because they

threatened Congregationalist uniformity, the Separatists were persecuted

and in Connecticut they were denied the same legal toleration enjoyed

by Baptists, Quakers and Anglicans.

The Baptists benefited the most from the Great Awakening.

Numerically small before the outbreak of revival, Baptist churches

experienced growth during the last half of the 18th century. By 1804,

there were over 300 Baptist churches in New England. This growth was

primarily due to an influx of former New Light Congregationalists who

became convinced of Baptist doctrines, such as believer's baptism. In some cases, entire Separatist congregations accepted Baptist beliefs as a body.

As revivalism spread through the Presbyterian churches, the old

disputes between the subscription and anti-subscription parties were

recast into conflict between the anti-revival "Old Side" and pro-revival

"New Side", respectively. At issue was the place of revivalism in

American Presbyterianism, specifically the "relation between doctrinal

orthodoxy and experimental knowledge of Christ."

The New Side, led by Gilbert Tennent and Jonathan Dickinson, believed

that strict adherence to orthodoxy was meaningless if one lacked a

personal religious experience, a sentiment expressed in Tennent's 1739

sermon "The Danger of an Unconverted Ministry". Whitefield's tour had

helped the revival party grow and only worsened the Old Side–New Side Controversy. When the Synod of Philadelphia met in May 1741, the Old Side expelled the New Side, which then reorganized itself into the Synod of New York.

Aftermath

Historian John Howard Smith noted that the Great Awakening made sectarianism an essential characteristic of American Christianity.

While the Awakening divided many Protestant churches between Old and

New Lights, it also unleashed a strong impulse towards

interdenominational unity among the various Protestant denominations.

Evangelicals considered the new birth to be "a bond of fellowship that

transcended disagreements on fine points of doctrine and polity",

allowing Anglicans, Presbyterians, Congregationalists and others to

cooperate across denominational lines.

While divisions between Old and New Lights remained, New Lights

became less radical over time and evangelicalism became more mainstream.

By 1758, the Old Side–New Side split in the Presbyterian Church had

been healed and the two factions reunited. In part, this was due to the

growth of the New Side and the numerical decline of the Old Side. In

1741, the pro-revival party had around 22 ministers, but this number had

increased to 73 by 1758.

While the fervor of the Awakening would fade, the acceptance of

revivalism and insistence on personal conversion would remain recurring

features in 18th and 19th-century Presbyterianism.

The Great Awakening inspired the creation of evangelical

educational institutions. In 1746, New Side Presbyterians founded what

would become Princeton University. In 1754, the efforts of Eleazar Wheelock led to what would become Dartmouth College, originally established to train Native American boys for missionary work among their own people.

While initially resistant, well-established Yale University came to

embrace the revivalism and played a leading role in American

evangelicalism for the next century.

Revival theology

The Great Awakening was not the first time that Protestant churches

had experienced revival; however, it was the first time a common evangelical identity had emerged based on a fairly uniform understanding of salvation, preaching the gospel and conversion. Revival theology focused on the way of salvation, the stages by which a person receives Christian faith and then expresses that faith in the way they live.

The major figures of the Great Awakening, such as George Whitefield, Jonathan Edwards, Gilbert Tennent, Jonathan Dickinson and Samuel Davies, were moderate evangelicals who preached a pietistic form of Calvinism heavily influenced by the Puritan tradition, which held that religion was not only an intellectual exercise but also had to be felt and experienced in the heart. This moderate revival theology consisted of a three stage process. The first stage was conviction of sin, which was spiritual preparation for faith by God's law and the means of grace. The second stage was conversion, in which a person experienced spiritual illumination, repentance and faith. The third stage was consolation, which was searching and receiving assurance of salvation. This process generally took place over an extended time.

Conviction of sin

Conviction of sin was the stage that prepared someone to receive salvation, and this stage often lasted weeks or months. When under conviction, nonbelievers realized they were guilty of sin and under divine condemnation and subsequently faced feelings of sorrow and anguish. When revivalists preached, they emphasized God's moral law to highlight the holiness of God and to spark conviction in the unconverted. Jonathan Edwards' sermon "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God" is an example of such preaching.

As Calvinists, revivalists also preached the doctrines of original sin and unconditional election. Due to the fall of man,

humans are naturally inclined to rebel against God and unable to

initiate or merit salvation, according to the doctrine of original sin.

Unconditional election relates to the doctrine of predestination—that before the creation

of the world God determined who would be saved (the elect) on the basis

of his own choosing. The preaching of these doctrines resulted in the

convicted feeling both guilty and totally helpless, since God was in

complete control over whether they would be saved or not.

Revivalists counseled those under conviction to apply the means

of grace to their lives. These were spiritual disciplines such as prayer, Bible

study, church attendance and personal moral improvement. While no human

action could produce saving faith, revivalists taught that the means of

grace might make conversion more likely.

An issue that had to be addressed were the intense physical and

emotional reactions to conviction experienced during the Awakening. Samuel Blair described such responses to his preaching in 1740, "Several would be overcome and fainting;

others deeply sobbing, hardly able to contain, others crying in a most

dolorous manner, many others more silently weeping. ... And sometimes

the soul exercises of some, thought comparatively but very few, would so

far affect their bodies, as to occasion some strange, unusual bodily

motions."

Moderate evangelicals took a cautious approach to this issue, neither

encouraging or discouraging these responses, but they recognized that

people might express their conviction in different ways.

Conversion

The conviction stage lasted so long because potential converts were waiting to find evidence of regeneration

within their lives. The revivalists believed regeneration or the new

birth was not simply an outward profession of faith or conformity to

Christianity. They believed it was an instantaneous, supernatural work

of the Holy Spirit providing someone with "a new awareness of the beauty

of Christ, new desires to love God, and a firm commitment to follow

God's holy law."

The reality of regeneration was discerned through self-examination, and

while it occurred instantaneously, a convert might only gradually

realize it had occurred.

Regeneration was always accompanied by saving faith, repentance

and love for God—all aspects of the conversion experience, which

typically lasted several days or weeks under the guidance of a trained

pastor.

True conversion began when the mind opened to a new awareness and love

of the gospel message. Following this illumination, converts placed

their faith in Christ, depending on him alone for salvation. At the same

time, a hatred of sin and a commitment to eliminate it from the heart

would take hold, setting the foundation for a life of repentance or

turning away from sin. Revivalists distinguished true conversion (which

was motivated by love of God and hatred of sin) from false conversion

(which was motivated by fear of hell).

Consolation

True

conversion meant that a person was among the elect, but even a person

with saving faith might doubt his election and salvation. Revivalists

taught that assurance of salvation was the product of Christian maturity

and sanctification. Converts were encouraged to seek assurance through self-examination of their own spiritual progress. The treatise Religious Affections

by Jonathan Edwards was written to help converts examine themselves for

the presence of genuine "religious affections" or spiritual desires,

such as selfless love of God, certitude in the divine inspiration of the gospel, and other Christian virtues.

It was not enough, however, to simply reflect on past

experiences. Revivalists taught that assurance could only be gained

through actively seeking to grow in grace and holiness through moritification of sin and utilizing the means of grace. In Religious Affections,

the last sign addressed by Edwards was "Christian practice", and it was

this sign to which he gave the most space in his treatise. The search

for assurance required conscious effort on the part of a convert and

took months or even years to achieve.

Impact on individuals

The new style sermons and the way in which people practiced their faith breathed new life into religion in America.

Participants became passionately and emotionally involved in their

religion, rather than passively listening to intellectual discourse in a

detached manner. Ministers who used this new style of preaching were

generally called "new lights", while the preachers who remained

unemotional were referred to as "old lights". People affected by the

revival began to study the Bible at home. This effectively decentralized

the means of informing the public on religious matters and was akin to

the individualistic trends present in Europe during the Protestant

Reformation.

Women

The Awakening played a major role in the lives of women, though they were rarely allowed to preach or take leadership roles.

A deep sense of religious enthusiasm encouraged women, especially to

analyze their feelings, share them with other women, and write about

them. They became more independent in their decisions, as in the choice

of a husband.

This introspection led many women to keep diaries or write memoirs. The

autobiography of Hannah Heaton (1721–94), a farm wife of North Haven, Connecticut, tells of her experiences in the Great Awakening, her encounters with Satan, her intellectual and spiritual development, and daily life on the farm.

Phillis Wheatley

was the first published black female poet, and she was converted to

Christianity as a child after she was brought to America. Her beliefs

were overt in her works; she describes the journey of being taken from a

Pagan land to be exposed to Christianity in the colonies in a poem

entitled "On Being Brought from Africa to America."

Wheatley became so influenced by the revivals and especially George

Whitefield that she dedicated a poem to him after his death in which she

referred to him as an "Impartial Saviour".

Sarah Osborn adds another layer to the role of women during the

Awakening. She was a Rhode Island schoolteacher, and her writings offer a

fascinating glimpse into the spiritual and cultural upheaval of the

time period, including a 1743 memoir, various diaries and letters, and

her anonymously published The Nature, Certainty and Evidence of True Christianity (1753).

African Americans

The

First Great Awakening led to changes in Americans' understanding of

God, themselves, the world around them, and religion. In the southern

Tidewater and Low Country, northern Baptist and Methodist

preachers converted both white and black people. Some were enslaved at

their time of conversion while others were free. Caucasians began to

welcome dark-skinned individuals into their churches, taking their

religious experiences seriously, while also admitting them into active

roles in congregations as exhorters, deacons, and even preachers,

although the last was a rarity.

The message of spiritual equality appealed to many slaves, and,

as African religious traditions continued to decline in North America,

black people accepted Christianity in large numbers for the first time.

Evangelical leaders in the southern colonies had to deal with the

issue of slavery much more frequently than those in the North. Still,

many leaders of the revivals proclaimed that slaveholders should educate

their slaves so that they could become literate and be able to read and

study the Bible. Many Africans were finally provided with some sort of

education.

George Whitefield's sermons reiterated an egalitarian message,

but only translated into a spiritual equality for Africans in the

colonies who mostly remained enslaved. Whitefield was known to criticize

slaveholders who treated their slaves cruelly and those who did not

educate them, but he had no intention to abolish slavery. He lobbied to

have slavery reinstated in Georgia and proceeded to become a slave

holder himself.

Whitefield shared a common belief held among evangelicals that, after

conversion, slaves would be granted true equality in Heaven. Despite his

stance on slavery, Whitefield became influential to many Africans.

Samuel Davies was a Presbyterian minister who later became the fourth president of Princeton University.

He was noted for preaching to African slaves who converted to

Christianity in unusually large numbers, and is credited with the first

sustained proselytization of slaves in Virginia.

Davies wrote a letter in 1757 in which he refers to the religious zeal

of an enslaved man whom he had encountered during his journey. "I am a

poor slave, brought into a strange country, where I never expect to

enjoy my liberty. While I lived in my own country, I knew nothing of

that Jesus I have heard you speak so much about. I lived quite careless

what will become of me when I die; but I now see such a life will never

do, and I come to you, Sir, that you may tell me some good things,

concerning Jesus Christ, and my Duty to GOD, for I am resolved not to

live any more as I have done."

Davies became accustomed to hearing such excitement from many

blacks who were exposed to the revivals. He believed that blacks could

attain knowledge equal to whites if given an adequate education, and he

promoted the importance for slaveholders to permit their slaves to

become literate so that they could become more familiar with the

instructions of the Bible.

The emotional worship of the revivals appealed to many Africans,

and African leaders started to emerge from the revivals soon after they

converted in substantial numbers. These figures paved the way for the

establishment of the first black congregations and churches in the

American colonies. Before the American Revolution, the first black Baptist churches were founded in the South in Virginia, South Carolina, and Georgia; two black Baptist churches were founded in Petersburg, Virginia.

Scholarly interpretation

The idea of a "great awakening" has been contested by historian Jon Butler as vague and exaggerated. He suggested that historians abandon the term Great Awakening

because the 18th-century revivals were only regional events that

occurred in only half of the American colonies and their effects on

American religion and society were minimal. Historians have debated whether the Awakening had a political impact on the American Revolution which took place soon after. Professor Alan Heimert sees a major impact, but most historians think it had only a minor impact.