The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival

during the early 19th century in the United States. The movement began

around 1790, gained momentum by 1800 and, after 1820, membership rose

rapidly among Baptist and Methodist congregations whose preachers led the movement. It was past its peak by the late 1850s. The Second Great Awakening reflected Romanticism characterized by enthusiasm, emotion, and an appeal to the supernatural. It rejected the skeptical rationalism and deism of the Enlightenment.

The revivals enrolled millions of new members in existing

evangelical denominations and led to the formation of new denominations.

Many converts believed that the Awakening heralded a new millennial age.

The Second Great Awakening stimulated the establishment of many reform

movements designed to remedy the evils of society before the anticipated

Second Coming of Jesus Christ.

Historians named the Second Great Awakening in the context of the First Great Awakening of the 1730s and 1750s and of the Third Great Awakening

of the late 1850s to early 1900s. These revivals were part of a much

larger Romantic religious movement that was sweeping across Europe at

the time, mainly throughout England, Scotland, and Germany.

Spread of revivals

Background

Like the First Great Awakening a half century earlier, the Second Great Awakening in North America reflected Romanticism characterized by enthusiasm, emotion, and an appeal to the super-natural. It rejected the skepticism, deism, Unitarianism, and rationalism left over from the American Enlightenment, about the same time that similar movements flourished in Europe. Pietism was sweeping Germanic countries and evangelicalism was waxing strong in England.

The Second Great Awakening occurred in several episodes and over

different denominations; however, the revivals were very similar. As the most effective form of evangelizing during this period, revival meetings cut across geographical boundaries. The movement quickly spread throughout Kentucky, Indiana, Tennessee, and southern Ohio,

as well as other regions of the United States and Canada. Each

denomination had assets that allowed it to thrive on the frontier. The

Methodists had an efficient organization that depended on itinerant

ministers, known as circuit riders, who sought out people in remote

frontier locations. The circuit riders came from among the common

people, which helped them establish rapport with the frontier families

they hoped to convert.

Theology

Postmillennialism

theology dominated American Protestantism in the first half of the 19th

century. Postmillennialists believed that Christ will return to earth

after the "millennium", which could entail either a literal 1,000 years

or a figurative "long period" of peace and happiness. Christians thus

had a duty to purify society in preparation for that return. This duty

extended beyond American borders to include Christian Restorationism.

George Fredrickson argues that Postmillennial theology "was an impetus

to the promotion of Progressive reforms, as historians have frequently

pointed out."

During the Second Great Awakening of the 1830s, some diviners expected

the millennium to arrive in a few years. By the 1840s, however, the

great day had receded to the distant future, and postmillennialism

became a more passive religious dimension of the wider middle-class pursuit of reform and progress.

Burned-over district

In the early nineteenth century, western New York State was called the "burned-over district" because of the highly publicized revivals that crisscrossed the region. Charles Finney, a leading revivalist active in the area, coined the term.

Linda K. Pritchard uses statistical data to show that compared to the

rest of New York State, the Ohio River Valley in the lower Midwest, and

the country as a whole, the religiosity of the Burned-over District was

typical rather than exceptional.

West and Tidewater South

On the American Frontier, evangelical denominations, especially Methodists and Baptists,

sent missionary preachers and exhorters to meet the people in the

backcountry in an effort to support the growth of church membership and

the formation of new congregations. Another key component of the revivalists' techniques was the camp meeting. These outdoor religious gatherings originated from field meetings and the Scottish Presbyterians' "Holy Fairs," which were brought to America in the mid-eighteenth century from Ireland, Scotland, and Britain’s border counties. Most of the Scots-Irish immigrants before the American Revolutionary War settled in the back country of Pennsylvania and down the spine of the Appalachian Mountains in present-day Maryland and Virginia,

where Presbyterian emigrants and Baptists held large outdoor gatherings

in the years prior to the war. The Presbyterians and Methodists

sponsored similar gatherings on a regular basis after the Revolution.

The denominations that encouraged the revivals were based on an

interpretation of man's spiritual equality before God, which led them to

recruit members and preachers from a wide range of classes and all

races. Baptists and Methodist revivals were successful in some parts of

the Tidewater South, where an increasing number of common planters, plain folk, and slaves were converted.

West

In the newly settled frontier regions, the revival was implemented

through camp meetings. These often provided the first encounter for some

settlers with organized religion, and they were important as social

venues. The camp meeting was a religious service of several days' length

with preachers. Settlers in thinly populated areas gathered at the camp

meeting for fellowship as well as worship. The sheer exhilaration of

participating in a religious revival with crowds of hundreds and perhaps

thousands of people inspired the dancing, shouting, and singing

associated with these events. The revivals also followed an arc of great

emotional power, with an emphasis on the individual's sins and need to

turn to Christ, and a sense of restoring personal salvation. This

differed from the Calvinists' belief in predestination as outlined in

the Westminster Confession of Faith,

which emphasized the inability of men to save themselves and decreed

that the only way to be saved was by God's electing grace. Upon their return home, most converts joined or created small local churches, which grew rapidly.

The Revival of 1800 in Logan County, Kentucky,

began as a traditional Presbyterian sacramental occasion. The first

informal camp meeting began in June, when people began camping on the

grounds of the Red River Meeting House. Subsequent meetings followed at the nearby Gasper

River and Muddy River congregations. All three of these congregations

were under the ministry of James McGready. A year later, in August 1801,

an even larger sacrament occasion that is generally considered to be

America’s first camp meeting was held at Cane Ridge in Bourbon County, Kentucky, under Barton W. Stone (1772–1844) with numerous Presbyterian,

Baptist, and Methodist ministers participating in the services. The

six-day gathering attracting perhaps as many as 20,000 people, although

the exact number of attendees was not formally recorded. Due to the

efforts of such leaders as Stone and Alexander Campbell

(1788–1866), the camp meeting revival spread religious enthusiasm and

became a major mode of church expansion, especilly for the Methodists

and Baptists.

Presbyterians and Methodists initially worked together to host the

early camp meetings, but the Presbyterians eventually became less

involved because of the noise and often raucous activities that occurred

during the protracted sessions.

As a result of the Revival of 1800, the Cumberland Presbyterian Church emerged in Kentucky and became a strong support of the revivalist movement. Cane Ridge was also instrumental in fostering what became known as the Restoration Movement, which consisted of non-denominational churches committed to what they viewed as the original, fundamental Christianity of the New Testament. Churches with roots in this movement include the Churches of Christ, Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), and the Evangelical Christian Church in Canada. The congregations of these denomination were committed to individuals' achieving a personal relationship with Christ.

Church membership soars

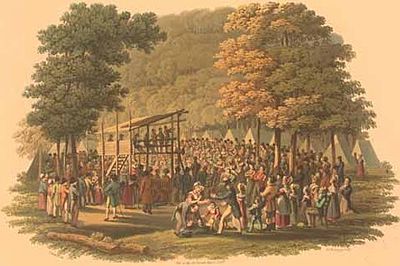

1839 Methodist camp meeting

The Methodist circuit riders and local Baptist preachers made

enormous gains in increasing church membership. To a lesser extent the Presbyterians also gained members, particularly with the Cumberland Presbyterian Church

in sparsely settled areas. As a result, the numerical strength of the

Baptists and Methodists rose relative to that of the denominations

dominant in the colonial period—the Anglicans, Presbyterians,

Congregationalists. Among the new denominations that grew from the

religious ferment of the Second Great Awakening are the Churches of Christ, Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), the Seventh-day Adventist Church, and the Evangelical Christian Church in Canada.

The converts during the Second Great Awakening were predominantly

female. A 1932 source estimated at least three female converts to every

two male converts between 1798 and 1826. Young people (those under 25)

also converted in greater numbers, and were the first to convert.

Subgroups

Adventism

The Advent Movement emerged in the 1830s and 1840s in North America, and was preached by ministers such as William Miller, whose followers became known as Millerites. The name refers to belief in the soon Second Advent of Jesus (popularly known as the Second coming) and resulted in several major religious denominations, including Seventh-day Adventists and Advent Christians.

Holiness movement

Though its roots are in the First Great Awakening and earlier, a re-emphasis on Wesleyan teachings on sanctification emerged during the Second Great Awakening, leading to a distinction between Mainline Methodism and Holiness churches.

Restoration Movement

The idea of restoring a "primitive" form of Christianity grew in popularity in the U.S. after the American Revolution.

This desire to restore a purer form of Christianity without an

elaborate hierarchy contributed to the development of many groups during

the Second Great Awakening, including the Mormons, Baptists and Shakers. Several factors made the restoration sentiment particularly appealing during this time period:

- To immigrants in the early 19th century, the land in the United States seemed pristine, edenic and undefiled – "the perfect place to recover pure, uncorrupted and original Christianity" – and the tradition-bound European churches seemed out of place in this new setting.

- A primitive faith based on the Bible alone promised a way to sidestep the competing claims of the many denominations available and for congregations to find assurance of being right without the security of an established national church.

The Restoration Movement began during, and was greatly influenced by, the Second Great Awakening. While the leaders of one of the two primary groups making up this movement, Thomas Campbell and Alexander Campbell,

resisted what they saw as the spiritual manipulation of the camp

meetings, the revivals contributed to the development of the other major

branch, led by Barton W. Stone.

The Southern phase of the Awakening "was an important matrix of Barton

Stone's reform movement" and shaped the evangelistic techniques used by

both Stone and the Campbells.

Culture and society

Efforts to apply Christian teaching to the resolution of social problems presaged the Social Gospel

of the late 19th century. Converts were taught that to achieve

salvation they needed not just to repent personal sin but also work for

the moral perfection of society, which meant eradicating sin in all its

forms. Thus, evangelical converts were leading figures in a variety of

19th century reform movements.

Congregationalists

set up missionary societies to evangelize the western territory of the

northern tier. Members of these groups acted as apostles for the faith,

and also as educators and exponents of northeastern urban culture. The

Second Great Awakening served as an "organizing process" that created "a

religious and educational infrastructure" across the western frontier

that encompassed social networks, a religious journalism that provided

mass communication, and church-related colleges. Publication and education societies promoted Christian education; most notable among them was the American Bible Society, founded in 1816. Women made up a large part of these voluntary societies.

The Female Missionary Society and the Maternal Association, both active

in Utica, NY, were highly organized and financially sophisticated

women's organizations responsible for many of the evangelical converts

of the New York frontier.

There were also societies that broadened their focus from

traditional religious concerns to larger societal ones. These

organizations were primarily sponsored by affluent women. They did not

stem entirely from the Second Great Awakening, but the revivalist

doctrine and the expectation that one's conversion would lead to

personal action accelerated the role of women's social benevolence work. Social activism influenced abolition groups and supporters of the Temperance movement.

They began efforts to reform prisons and care for the handicapped and

mentally ill. They believed in the perfectibility of people and were

highly moralistic in their endeavors.

Slaves and free Africans

Baptists and Methodists in the South preached to slaveholders and slaves alike. Conversions and congregations started with the First Great Awakening,

resulting in Baptist and Methodist preachers being authorized among

slaves and free African Americans more than a decade before 1800. "Black Harry" Hosier, an illiterate freedman who drove Francis Asbury on his circuits, proved to be able to memorize large passages of the Bible

verbatim and became a cross-over success, as popular among white

audiences as the black ones Asbury had originally intended for him to

minister. His sermon at Thomas Chapel in Chapeltown, Delaware, in 1784 was the first to be delivered by a black preacher directly to a white congregation.

Despite being called the "greatest orator in America" by Benjamin Rush and one of the best in the world by Bishop Thomas Coke, Hosier was repeatedly passed over for ordination and permitted no vote during his attendance at the Christmas Conference that formally established American Methodism. Richard Allen,

the other black attendee, was ordained by the Methodists in 1799, but

his congregation of free African Americans in Philadelphia left the

church there because of its discrimination. They founded the African Methodist Episcopal

Church (AME) in Philadelphia. After first submitting to oversight by

the established Methodist bishops, several AME congregations finally

left to form the first independent African-American denomination in the

United States in 1816. Soon after, the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (AME Zion) was founded as another denomination in New York City.

Early Baptist congregations were formed by slaves and free

African Americans in South Carolina and Virginia. Especially in the

Baptist Church, African Americans were welcomed as members and as

preachers. By the early 19th century, independent African American

congregations numbered in the several hundred in some cities of the

South, such as Charleston, South Carolina, and Richmond and Petersburg, Virginia.

With the growth in congregations and churches, Baptist associations

formed in Virginia, for instance, as well as Kentucky and other states.

The revival also inspired slaves to demand freedom. In 1800, out

of African American revival meetings in Virginia, a plan for slave

rebellion was devised by Gabriel Prosser, although the rebellion was discovered and crushed before it started. Despite white attempts to control independent African American congregations, especially after the Nat Turner

Uprising of 1831, a number of African American congregations managed to

maintain their separation as independent congregations in Baptist

associations. State legislatures passed laws requiring them always to

have a white man present at their worship meetings.

Women

Women, who

made up the majority of converts during the Awakening, played a crucial

role in its development and focus. It is not clear why women converted

in larger numbers than men. Various scholarly theories attribute the

discrepancy to a reaction to the perceived sinfulness of youthful

frivolity, an inherent greater sense of religiosity in women, a communal

reaction to economic insecurity, or an assertion of the self in the

face of patriarchal rule. Husbands, especially in the South, sometimes

disapproved of their wives' conversion, forcing women to choose between

submission to God or their spouses. Church membership and religious

activity gave women peer support and place for meaningful activity

outside the home, providing many women with communal identity and shared

experiences.

Despite the predominance of women in the movement, they were not

formally indoctrinated or given leading ministerial positions. However,

women took other public roles; for example, relaying testimonials about

their conversion experience, or assisting sinners (both male and female)

through the conversion process. Leaders such as Charles Finney saw

women's public prayer as a crucial aspect in preparing a community for

revival and improving their efficacy in conversion.

Women also took crucial roles in the conversion and religious

upbringing of children. During the period of revival, mothers were seen

as the moral and spiritual foundation of the family, and were thus

tasked with instructing children in matters of religion and ethics.

The greatest change in women's roles stemmed from participation

in newly formalized missionary and reform societies. Women's prayer

groups were an early and socially acceptable form of women's

organization. In the 1830s, female moral reform societies rapidly spread

across the North making it the first predominantly female social

movement. Through women's positions in these organizations, women gained influence outside of the private sphere.

Changing demographics of gender also affected religious doctrine.

In an effort to give sermons that would resonate with the congregation,

ministers stressed Christ's humility and forgiveness, in what the

historian Barbara Welter calls a "feminization" of Christianity.

Prominent figures

- Richard Allen, founder, African Methodist Episcopal Church

- Francis Asbury, Methodist, circuit rider and founder of the Methodist Episcopal Church

- Henry Ward Beecher, Congregationalist, son of Lyman Beecher

- Lyman Beecher, Presbyterian

- Antoinette Brown Blackwell, Congregationalist & later Unitarian, the first ordained female minister in the United States

- Alexander Campbell, Presbyterian, and early leader of the Restoration Movement

- Thomas Campbell Presbyterian, then early leader of the Restoration Movement

- Peter Cartwright, Methodist

- Lorenzo Dow, Methodist

- Timothy Dwight IV, Congregationalist

- Charles Finney, Presbyterian & anti-Calvinist

- "Black Harry" Hosier, Methodist, the first African American to preach to a white congregation

- Ann Lee, Shakers

- Jarena Lee, Methodist, a female AME circuit rider

- Robert Matthews, cult following as Matthias the Prophet

- William Miller, Millerism, forerunner of Adventism

- Asahel Nettleton, Reformed

- Benjamin Randall, Free Will Baptist

- Joseph Smith, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- Barton Stone, Presbyterian non-Calvinist, then early leader of the Restoration Movement

- Nathaniel William Taylor, heterodox Calvinist

- Ellen G. White, Seventh-day Adventist Church

Political implications

Revivals

and perfectionist hopes of improving individuals and society continued

to increase from 1840 to 1865 across all major denominations, especially

in urban areas. Evangelists often directly addressed issues such as

slavery, greed, and poverty, laying the groundwork for later reform

movements. The influence of the Awakening continued in the form of more secular movements. In the midst of shifts in theology and church polity, American Christians began progressive movements to reform society during this period. Known commonly as antebellum reform, this phenomenon included reforms in against the consumption of alcohol, for women's rights and abolition of slavery, and a multitude of other issues faced by society.

The religious enthusiasm of the Second Great Awakening was echoed by the new political enthusiasm of the Second Party System.

More active participation in politics by more segments of the

population brought religious and moral issues into the political sphere.

The spirit of evangelical humanitarian reforms was carried on in the

antebellum Whig party.

Historians stress the understanding common among participants of

reform as being a part of God's plan. As a result, local churches saw

their roles in society in purifying the world through the individuals to

whom they could bring salvation, and through changes in the law and the

creation of institutions. Interest in transforming the world was

applied to mainstream political action, as temperance activists,

antislavery advocates, and proponents of other variations of reform

sought to implement their beliefs into national politics. While

Protestant religion had previously played an important role on the

American political scene, the Second Great Awakening strengthened the

role it would play.