Village near the coast of Sumatra

| |

| UTC time | 2004-12-26 00:58:53 |

|---|---|

| ISC event | 7453151 |

| USGS-ANSS | ComCat |

| Local date | 26 December 2004 |

| Local time | |

| Magnitude | 9.1–9.3 Mw |

| Depth | 30 km (19 mi) |

| Epicenter | 3.316°N 95.854°ECoordinates: 3.316°N 95.854°E |

| Type | Megathrust |

| Areas affected | Indian Ocean coastline areas |

| Total damage | US$15 billion |

| Max. intensity | IX (Violent) |

| Tsunami |

|

| Casualties | 227,898 dead |

The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake occurred at 00:58:53 UTC on 26 December, with an epicentre off the west coast of northern Sumatra. It was an undersea megathrust earthquake that registered a magnitude of 9.1–9.3 Mw, reaching a Mercalli intensity up to IX in certain areas. The earthquake was caused by a rupture along the fault between the Burma Plate and the Indian Plate.

A series of large tsunamis up to 30 metres (100 ft) high were created by the underwater seismic activity that became known collectively as the Boxing Day tsunamis. Communities along the surrounding coasts of the Indian Ocean were seriously affected, and the tsunamis killed an estimated 227,898 people in 14 countries. The Indonesian city of Banda Aceh reported the largest number of victims. The earthquake was one of the deadliest natural disasters in recorded history. The direct results caused major disruptions to living conditions and commerce particularly in Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India, and Thailand.

The earthquake was the third largest ever recorded and had the longest duration of faulting ever observed; between eight and ten minutes. It caused the planet to vibrate as much as 1 centimetre (0.4 inches), and it remotely triggered earthquakes as far away as Alaska. Its epicentre was between Simeulue and mainland Sumatra. The plight of the affected people and countries prompted a worldwide humanitarian response, with donations totaling more than US$14 billion. The event is known by the scientific community as the Sumatra–Andaman earthquake.

Earthquake

The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake was initially documented as having a moment magnitude of 8.8. In February 2005, scientists revised the estimate of the magnitude to 9.0. Although the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center has accepted these new numbers, the United States Geological Survey has so far not changed its estimate of 9.1. A 2006 study estimated a magnitude of Mw 9.1–9.3; Hiroo Kanamori of the California Institute of Technology estimates that Mw 9.2 is representative of the earthquake's size.The hypocentre of the main earthquake was approximately 160 km (100 mi) off the western coast of northern Sumatra, in the Indian Ocean just north of Simeulue island at a depth of 30 km (19 mi) below mean sea level (initially reported as 10 km (6.2 mi)). The northern section of the Sunda megathrust ruptured over a length of 1,300 km (810 mi). The earthquake (followed by the tsunami) was felt in Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, Myanmar, Thailand, Sri Lanka and the Maldives. Splay faults, or secondary "pop up faults", caused long, narrow parts of the sea floor to pop up in seconds. This quickly elevated the height and increased the speed of waves, destroying the nearby Indonesian town of Lhoknga.

Indonesia lies between the Pacific Ring of Fire along the north-eastern islands adjacent to New Guinea, and the Alpide belt that runs along the south and west from Sumatra, Java, Bali, Flores to Timor. The 2002 Sumatra earthquake is believed to have been a foreshock, preceding the main event by over two years.

Great earthquakes, such as the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake, are associated with megathrust events in subduction zones. Their seismic moments can account for a significant fraction of the global seismic moment across century-scale time periods. Of all the moment released by earthquakes in the 100 years from 1906 through 2005, roughly one-eighth was due to the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake. This quake, together with the Good Friday earthquake (Alaska, 1964) and the Great Chilean earthquake (1960), account for almost half of the total moment.

Since 1900, the only earthquakes recorded with a greater magnitude were the 1960 Great Chilean earthquake (Magnitude 9.5) and the 1964 Good Friday earthquake in Prince William Sound (Magnitude 9.2). The only other recorded earthquakes of magnitude 9.0 or greater were off Kamchatka, Russia, on 4 November 1952 (magnitude 9.0) and Tōhoku, Japan (magnitude 9.1) in March 2011. Each of these megathrust earthquakes also spawned tsunamis in the Pacific Ocean. However, in comparison to the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake, the death toll from these earthquakes was significantly lower, primarily because of the lower population density along the coasts near affected areas, the much greater distances to more populated coasts, and the superior infrastructure and warning systems in MEDCs (More Economically Developed Countries) such as Japan.

Other very large megathrust earthquakes occurred in 1868 (Peru, Nazca Plate and South American Plate); 1827 (Colombia, Nazca Plate and South American Plate); 1812 (Venezuela, Caribbean Plate and South American Plate) and 1700 (western North America, Juan de Fuca Plate and North American Plate). All of them are believed to be greater than magnitude 9, but no accurate measurements were available at the time.

Tectonic plates

Epicenter and associated aftershocks

The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake was unusually large in geographical

and geological extent. An estimated 1,600 kilometres (1,000 mi) of fault surface slipped (or ruptured) about 15 metres (50 ft) along the subduction zone where the Indian Plate

slides (or subducts) under the overriding Burma Plate. The slip did not

happen instantaneously but took place in two phases over several

minutes:

Seismographic and acoustic data indicate that the first phase involved a

rupture about 400 kilometres (250 mi) long and 100 kilometres (60 mi)

wide, 30 kilometres (19 mi) beneath the sea bed—the largest rupture ever

known to have been caused by an earthquake. The rupture proceeded at

about 2.8 kilometres per second (1.7 miles per second) (10,000 km/h or

6,200 mph), beginning off the coast of Aceh and proceeding north-westerly over about 100 seconds.

After a pause of about another 100 seconds, the rupture continued northwards towards the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

However, the northern rupture occurred more slowly than in the south,

at about 2.1 km/s (1.3 mi/s) (7,500 km/h or 4,700 mph), continuing north

for another five minutes to a plate boundary where the fault type

changes from subduction to strike-slip (the two plates slide past one another in opposite directions).

The Indian Plate is part of the great Indo-Australian Plate, which underlies the Indian Ocean and Bay of Bengal, and is moving north-east at an average of 6 centimetres per year (2.4 inches per year). The India Plate meets the Burma Plate (which is considered a portion of the great Eurasian Plate) at the Sunda Trench.

At this point the India Plate subducts beneath the Burma Plate, which

carries the Nicobar Islands, the Andaman Islands, and northern Sumatra.

The India Plate sinks deeper and deeper beneath the Burma Plate until

the increasing temperature and pressure drive volatiles

out of the subducting plate. These volatiles rise into the overlying

plate, causing partial melting and the formation of magma. The rising

magma intrudes into the crust above and exits the Earth's crust through

volcanoes in the form of a volcanic arc. The volcanic activity that results as the Indo-Australian Plate subducts the Eurasian Plate has created the Sunda Arc.

As well as the sideways movement between the plates, the 2004

Indian Ocean earthquake resulted in a rise of the sea floor by several

metres, displacing an estimated 30 cubic kilometres (7.2 cu mi) of water

and triggering devastating tsunami waves. The waves radiated outwards

along the entire 1,600-kilometre (1,000 mi) length of the rupture

(acting as a line source).

This greatly increased the geographical area over which the waves were

observed, reaching as far as Mexico, Chile, and the Arctic. The raising

of the sea floor significantly reduced the capacity of the Indian Ocean,

producing a permanent rise in the global sea level by an estimated 0.1

millimetres (0.004 in).

Aftershocks and other earthquakes

Initial earthquake and aftershocks measuring greater than 4.0 Mw from 26 December 2004 to 10 January 2005

Numerous aftershocks were reported off the Andaman Islands, the Nicobar Islands and the region of the original epicentre in the hours and days that followed. The magnitude 8.7 2005 Nias–Simeulue earthquake, which originated off the coast of the Sumatran island of Nias, is not considered an aftershock, despite its proximity to the epicenter, and was most likely triggered by stress changes associated with the 2004 event.

The earthquake produced its own aftershocks (some registering a

magnitude of as great as 6.1) and presently ranks as the third largest

earthquake ever recorded on the moment magnitude or Richter magnitude

scale.

Other aftershocks of up to magnitude 6.6 continued to shake the region daily for three or four months.

As well as continuing aftershocks, the energy released by the original

earthquake continued to make its presence felt well after the event. A

week after the earthquake, its reverberations could still be measured,

providing valuable scientific data about the Earth's interior.

The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake came just three days after a

magnitude 8.1 earthquake in an uninhabited region west of New Zealand's

subantarctic Auckland Islands, and north of Australia's Macquarie Island. This is unusual, since earthquakes of magnitude 8 or more occur only about once per year on average. However, the U.S. Geological Survey sees no evidence of a causal relationship between these events.

The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake is thought to have triggered activity in both Leuser Mountain and Mount Talang, volcanoes in Aceh province along the same range of peaks, while the 2005 Nias–Simeulue earthquake had sparked activity in Lake Toba, an ancient crater in Sumatra.

Energy released

The energy released on the Earth's surface (ME, which is the seismic potential for damage) by the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake was estimated at 1.1×1017 joules, or 26 megatons of TNT. This energy is equivalent to over 1,500 times that of the Hiroshima atomic bomb, but less than that of Tsar Bomba, the largest nuclear weapon ever detonated; however, the total physical work done MW (and thus energy) by the quake was 4.0×1022 joules (4.0×1029 ergs), the vast majority underground, which is over 360,000 times more than its ME, equivalent to 9,600 gigatons of TNT equivalent (550 million times that of Hiroshima) or about 370 years of energy use in the United States at 2005 levels of 1.08×1020 J. The only recorded earthquakes with a larger MW were the 1960 Chilean and 1964 Alaskan quakes, with 2.5×1023 joules (250 ZJ) and 7.5×1022 joules (75 ZJ) respectively.

The earthquake generated a seismic oscillation of the Earth's

surface of up to 20–30 cm (8–12 in), equivalent to the effect of the tidal forces caused by the Sun and Moon. The seismic waves of the earthquake were felt across the planet; as far away as the U.S. state of Oklahoma,

where vertical movements of 3 mm (0.12 in) were recorded. By February

2005, the earthquake's effects were still detectable as a 20 μm

(0.02 mm; 0.0008 in) complex harmonic oscillation of the Earth's

surface, which gradually diminished and merged with the incessant free

oscillation of the Earth more than 4 months after the earthquake.

Vertical-component ground motions recorded by the IRIS Consortium

Because of its enormous energy release and shallow rupture depth, the

earthquake generated remarkable seismic ground motions around the

globe, particularly due to huge Rayleigh (surface) elastic waves

that exceeded 1 cm (0.4 in) in vertical amplitude everywhere on Earth.

The record section plot displays vertical displacements of the Earth's

surface recorded by seismometers from the IRIS/USGS Global Seismographic

Network plotted with respect to time (since the earthquake initiation)

on the horizontal axis, and vertical displacements of the Earth on the

vertical axis (note the 1 cm scale bar at the bottom for scale). The

seismograms are arranged vertically by distance from the epicenter in

degrees. The earliest, lower amplitude signal is that of the

compressional (P) wave, which takes about 22 minutes to reach the other

side of the planet (the antipode;

in this case near Ecuador). The largest amplitude signals are seismic

surface waves that reach the antipode after about 100 minutes. The

surface waves can be clearly seen to reinforce near the antipode (with

the closest seismic stations in Ecuador), and to subsequently encircle

the planet to return to the epicentral region after about 200 minutes. A

major aftershock (magnitude 7.1) can be seen at the closest stations

starting just after the 200 minute mark. The aftershock would be

considered a major earthquake under ordinary circumstances but is

dwarfed by the mainshock.

The shift of mass and the massive release of energy slightly

altered the Earth's rotation. The exact amount is not yet known, but

theoretical models suggest the earthquake shortened the length of a day

by 2.68 microseconds, due to a decrease in the oblateness of the Earth. It also caused the Earth to minutely "wobble" on its axis by up to 2.5 cm (1 in) in the direction of 145° east longitude, or perhaps by up to 5 or 6 cm (2.0 or 2.4 in).

However, because of tidal effects of the Moon, the length of a day

increases at an average of 15 microseconds per year, so any rotational

change due to the earthquake will be lost quickly. Similarly, the

natural Chandler wobble

of the Earth, which in some cases can be up to 15 m (50 ft), will

eventually offset the minor wobble produced by the earthquake.

There was 10 m (33 ft) movement laterally and 4–5 m (13–16 ft)

vertically along the fault line. Early speculation was that some of the

smaller islands south-west of Sumatra, which is on the Burma Plate (the southern regions are on the Sunda Plate),

might have moved south-west by up to 36 m (120 ft), but more accurate

data released more than a month after the earthquake found the movement

to be about 20 cm (8 in). Since movement was vertical as well as lateral, some coastal areas may have been moved to below sea level. The Andaman and Nicobar Islands appear to have shifted south-west by around 1.25 m (4 ft 1 in) and to have sunk by 1 m (3 ft 3 in).

Seismic moment release of the largest earthquakes from 1906 to 2005

In February 2005, the Royal Navy vessel HMS Scott

surveyed the seabed around the earthquake zone, which varies in depth

between 1,000 and 5,000 m (550 and 2,730 fathoms; 3,300 and 16,400 ft).

The survey, conducted using a high-resolution, multi-beam sonar system,

revealed that the earthquake had made a huge impact on the topography of

the seabed. 1,500-metre-high (5,000 ft) thrust ridges created by

previous geologic activity along the fault had collapsed, generating

landslides several kilometres wide. One such landslide consisted of a

single block of rock some 100 m high and 2 km long (300 ft by 1.25 mi).

The momentum of the water displaced by tectonic uplift had also dragged

massive slabs of rock, each weighing millions of tons, as far as 10 km

(6 mi) across the seabed. An oceanic trench several kilometres wide was exposed in the earthquake zone.

The TOPEX/Poseidon and Jason-1 satellites happened to pass over the tsunami as it was crossing the ocean.

These satellites carry radars that measure precisely the height of the

water surface; anomalies in the order of 50 cm (20 in) were measured.

Measurements from these satellites may prove invaluable for the

understanding of the earthquake and tsunami. Unlike data from tide gauges

installed on shores, measurements obtained in the middle of the ocean

can be used for computing the parameters of the source earthquake

without having to compensate for the complex ways in which close

proximity to the coast changes the size and shape of a wave.

Tsunami

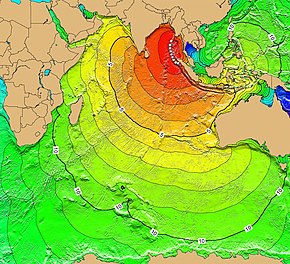

The tsunami's propagation

took 5 hours to reach Western Australia, 7 hours to reach the Arabian

Peninsula, and did not reach the South African coast until nearly

11 hours after the earthquake

The sudden vertical rise of the seabed by several metres during the

earthquake displaced massive volumes of water, resulting in a tsunami

that struck the coasts of the Indian Ocean. A tsunami that causes damage

far away from its source is sometimes called a teletsunami and is much more likely to be produced by vertical motion of the seabed than by horizontal motion.

The tsunami, like all others, behaved differently in deep water

than in shallow water. In deep ocean water, tsunami waves form only a

low, broad hump, barely noticeable and harmless, which generally travels

at a high speed of 500 to 1,000 km/h (310 to 620 mph); in shallow water

near coastlines, a tsunami slows down to only tens of kilometres per

hour but, in doing so, forms large destructive waves. Scientists

investigating the damage in Aceh found evidence that the wave reached a

height of 24 metres (80 ft) when coming ashore along large stretches of

the coastline, rising to 30 metres (100 ft) in some areas when traveling

inland.

Radar satellites recorded the heights of tsunami waves in deep water:

maximum height was at 60 centimetres (2 ft) two hours after the

earthquake, the first such observations ever made.

According to Tad Murty, vice-president of the Tsunami Society, the total energy of the tsunami waves was equivalent to about five megatons of TNT (20 petajoules),

which is more than twice the total explosive energy used during all of

World War II (including the two atomic bombs) but still a couple of orders of magnitude less than the energy released in the earthquake itself. In many places the waves reached as far as 2 km (1.2 mi) inland.

Because the 1,600 km (1,000 mi) fault affected by the earthquake

was in a nearly north-south orientation, the greatest strength of the

tsunami waves was in an east-west direction. Bangladesh, which lies at the northern end of the Bay of Bengal,

had few casualties despite being a low-lying country relatively near

the epicenter. It also benefited from the fact that the earthquake

proceeded more slowly in the northern rupture zone, greatly reducing the

energy of the water displacements in that region.

Maximum height of the waves that hit Indonesia

Coasts that have a landmass between them and the tsunami's location

of origin are usually safe; however, tsunami waves can sometimes diffract around such landmasses. Thus, the state of Kerala

was hit by the tsunami despite being on the western coast of India, and

the western coast of Sri Lanka suffered substantial impacts. Distance

alone was no guarantee of safety, as Somalia was hit harder than

Bangladesh despite being much farther away.

Because of the distances involved, the tsunami took anywhere from fifteen minutes to seven hours to reach the coastlines.

The northern regions of the Indonesian island of Sumatra were hit

quickly, while Sri Lanka and the east coast of India were hit roughly

90 minutes to two hours later. Thailand was struck about two hours later

despite being closer to the epicentre, because the tsunami traveled

more slowly in the shallow Andaman Sea off its western coast.

The tsunami was noticed as far as Struisbaai

in South Africa, about 8,500 km (5,300 mi) away, where a 1.5 m (5 ft)

high tide surged on shore about 16 hours after the earthquake. It took a

relatively long time to reach Struisbaai at the southernmost point of

Africa, probably because of the broad continental shelf off South Africa

and because the tsunami would have followed the South African coast

from east to west. The tsunami also reached Antarctica, where tidal

gauges at Japan's Showa Base recorded oscillations of up to a metre (3 ft 3 in), with disturbances lasting a couple of days.

Some of the tsunami's energy escaped into the Pacific Ocean,

where it produced small but measurable tsunamis along the western coasts

of North and South America, typically around 20 to 40 cm (7.9 to

15.7 in). At Manzanillo, Mexico, a 2.6 m (8 ft 6 in) crest-to-trough tsunami was measured. As well, the tsunami was large enough to be detected in Vancouver,

which puzzled many scientists, as the tsunamis measured in some parts

of South America were larger than those measured in some parts of the

Indian Ocean. It has been theorized that the tsunamis were focused and

directed at long ranges by the mid-ocean ridges which run along the margins of the continental plates.

Early signs and warnings

Maximum recession of tsunami waters at Kata Noi Beach at 10:25 a.m., prior to the third—and strongest—tsunami wave

Despite a delay of up to several hours between the earthquake and the

impact of the tsunami, nearly all of the victims were taken by

surprise. There were no tsunami warning systems in the Indian Ocean to detect tsunamis or to warn the general population living around the ocean.

Tsunami detection is not easy because while a tsunami is in deep water,

it has little height and a network of sensors is needed to detect it.

Setting up the communications infrastructure to issue timely warnings is

an even bigger problem, particularly in a relatively impoverished part

of the world.

Tsunamis are more frequent in the Pacific Ocean

than in other oceans because of earthquakes in the "Ring of Fire".

Although the extreme western edge of the Ring of Fire extends into the

Indian Ocean (the point where the earthquake struck), no warning system

exists in that ocean. Tsunamis there are relatively rare despite

earthquakes being relatively frequent in Indonesia. The last major

tsunami was caused by the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa.

Not every earthquake produces large tsunamis: on 28 March 2005, a

magnitude 8.7 earthquake hit roughly the same area of the Indian Ocean

but did not result in a major tsunami.

The first warning sign of a possible tsunami is the earthquake

itself. However, tsunamis can strike thousands of kilometres away where

the earthquake is felt only weakly or not at all. Also, in the minutes

preceding a tsunami strike, the sea often recedes temporarily from the

coast, something which was observed on the eastern side of the rupture

zone of the earthquake such as around the coastlines of Aceh province, Phuket island, and Khao Lak area in Thailand, Penang island of Malaysia, and the Andaman and Nicobar islands.

Around the Indian Ocean, this rare sight reportedly induced people,

especially children, to visit the coast to investigate and collect

stranded fish on as much as 2.5 km (1.6 mi) of exposed beach, with fatal

results.

However, not all tsunamis cause this "disappearing sea" effect. In some

cases, there are no warning signs at all: the sea will suddenly swell

without retreating, surprising many people and giving them little time

to flee.

Tsunami wave field in the Bay of Bengal an hour after the earthquake

One of the few coastal areas to evacuate ahead of the tsunami was on the Indonesian island of Simeulue, close to the epicentre. Island folklore recounted an earthquake and tsunami in 1907,

and the islanders fled to inland hills after the initial shaking and

before the tsunami struck. These tales and oral folklore from previous

generations may have helped the survival of the inhabitants. On Maikhao Beach in north Phuket City, Thailand, a 10-year-old British tourist named Tilly Smith

had studied tsunamis in geography at school and recognised the warning

signs of the receding ocean and frothing bubbles. She and her parents

warned others on the beach, which was evacuated safely. John Chroston,

a biology teacher from Scotland, also recognised the signs at Kamala

Bay north of Phuket, taking a busload of vacationers and locals to

safety on higher ground.

Anthropologists had initially expected the aboriginal population of the Andaman Islands to be badly affected by the tsunami and even feared the already depopulated Onge tribe could have been wiped out. Many of the aboriginal tribes evacuated and suffered fewer casualties, however.

Oral traditions developed from previous earthquakes helped the

aboriginal tribes escape the tsunami. For example, the folklore of the

Onges talks of "huge shaking of ground followed by high wall of water".

Almost all of the Onge people seemed to have survived the tsunami.

Indonesia

Tsunami inundation height can be seen on a house in Banda Aceh

The tsunami struck the west and north coasts of northern Sumatra, particularly in Aceh Province, Indonesia, during the early morning. At Ulee Lheue in Banda Aceh, a survivor described three waves, with the first wave rising only to the foundation of the buildings.

This was followed by a large withdrawal of the sea before the second and third waves hit.

The tsunami reached shore 15–20 minutes after the earthquake, and the

second wave was bigger than the first. A local resident living at Banda

Aceh stated that the wave was "higher than my house". Another residenton

the outskirt of the city said that the tsunami was "like a wall, very

black" in colour and had a "distinct sound" getting louder as it neared

the coast.

The maximum runup height of the tsunami was measured at a hill between Lhoknga and Leupung, on the west coast of the northern tip of Sumatra, near Banda Aceh, and reached more than 30 m (100 ft).

The tsunami heights in Sumatra:

- 15–30 m (49–98 ft) on the west coast of Aceh;

- 6–12 m (19.7–39.4 ft) on the Banda Aceh coast;

- 6 m (19.7 ft) on the Krueng Raya coast;

- 5 m (16.4 ft) on the Sigli coast;

- 3–6 m (9.8–19.7 ft) on the north coast of Weh Island directly facing the tsunami source

- 3 m (9.8 ft) on the opposite side of the coast of Weh Island facing the tsunami.

The tsunami height on the Banda Aceh coast was lower than half of

that on the west coast. The tsunami height was reduced by half from 12 m

(39.4 ft) at Ulee Lheue to 6 m (19.7 ft) a further 8 km (5.0 miles) to

the northeast. The inundation was observed to lie 3–4 km (1.9–2.5

miles) inland throughout the city. Flow depths over the ground were

observed to be over 9 m (29.5 ft) in the seaside section of Ulee Lheue

and tapered landward.

The level of destruction was more extreme on the northwestern

flank of the city in the areas immediately inland of the aquaculture

ponds. The area toward the sea was wiped clean of nearly every

structure, while closer to the river dense construction in a commercial

district showed the effects of severe flooding. The flow depth was just

at the level of the second floor, and there were large amounts of debris

piled along the streets and in the ground-floor storefronts.

Apung 1, a 2,600 ton vessel, was flung some 2 to 3 km inland

Within 2–3 km (1.2–1.9 miles) of the shoreline, houses, except for

strongly-built reinforced concrete ones with brick walls, which seemed

to have been partially damaged by the earthquake before the tsunami

attack, were swept away or destroyed by the tsunami.

Three small islands: Weh, Breueh, and Nasi, lie just north of the

capital city. The tsunami effects on two of the islands, Breueh and

Nasi were extreme, with a runup of 10–20 m (33–66 ft) on the

west-facing shores. Coastal villages were destroyed by the tsunami

waves. On Pulau Weh, however, the island experienced strong surges in the port of Sabang,

yet there was little damage with a reported runup values of 3–5 m

(9.8–16.4 ft), sheltered from the direct tsunami attack by the islands

to the southwest.

In Lhoknga, a town in Aceh Besar Regency,

Aceh Special Region, on the western side of the island of Sumatra,

13 km (8.08 miles) southwest of Banda Aceh was flattened and destroyed

by the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami, where its population dwindled from 7,500

to 400. Tsunami waves were almost 30 m (98.4 ft) high. Eyewitnesses

reported 10 to 12 waves, the second and third being the highest. The sea

receded ten minutes after the earthquake and the first wave came

rapidly landward from the southwest as a turbulent flow with depths

ranging from 0.5 to 2.5 m (1.64–8.20 ft) high.

The second and third waves were 15–30 m (49.2–98.4 ft) high at

the coast and were described as having an appearance like a surf wave

(cobra-shaped) but "taller than the coconut trees" and "like a

mountain".

The second and third tsunami waves changed appearance from a surfing

waveform to a huge tsunami bore, similar to tsunami witnessed in Khao Lak, Thailand.

Overturned cement carrier in Lhoknga

The second wave was the largest; it came from the west-southwest

within five minutes of the first wave. The tsunami stranded cargo ships

and barges and destroyed a cement factory near the Lampuuk coast.

Areas surveyed by scientists show runup heights of over 20 m (65.6 ft)

on the northwest coast of Sumatra in Aceh Province with a maximum runup

of 51 m (167.3 ft).

In Meulaboh based on survivor testimonies,

the tsunami arrived after the sea receded about 500 m (0.31 miles),

followed by an advancing small tsunami. The second and third destructive

waves arrived later, which exceeded the height of the coconut trees.

The inundation distance is about 5 km (3.1 miles).

Such high and fast waves arising from the epicentre by a megathrust earthquake

were later found to be due to splay faults, secondary faults arising

due to cracking of the sea floor to just upwards in seconds, causing

waves' speed and height to increase. A large slip of 30 m (98.4 ft) was

estimated

on the subfault off the west coast of Aceh Province. Another factor is

subsidence at Banda Aceh (20–60 cm), Peukan Bada (g.t. 20 cm), Lhoknga

and Leupung (g.t. 1.5 m).

Other towns on Aceh's west coast hit by the disaster included Leupung, Lhokruet, Lamno, Patek, Calang, Teunom, and the island of Simeulue. Affected or destroyed towns on the region's north and east coast were Pidie Regency, Samalanga, Panteraja, and Lhokseumawe.

The high fatality rate in the area was mainly due to unpreparedness.

Helicopter surveys showed entire settlements virtually destroyed with

destruction miles inland with only some mosques left standing.

Sri Lanka

Fishing boat stranded in Batticaloa

The tsunami first struck on the eastern coast and subsequently refracted around the southern point of Sri Lanka

(Dondra Head). The refracted tsunami waves inundated the southwestern

part of Sri Lanka after some of its energy reflected from impact with

the Maldives.

Sri Lanka is located 1,700 km (1056.33 miles) from the epicenter and

the tsunami source. The tsunami hit the entire coastline of Sri Lanka

around 2 hours after the earthquake.

The first tsunami waves initially caused a small flood (positive

wave) as it struck the Sri Lankan coastline. Moments later, the ocean

floor was exposed to as much as 1 km (0.62 miles) in places due to

drawback (negative wave), which was followed by a massive second tsunami

wave. The construction of seawalls and breakwaters reduced the power of

waves at some locations.

The largest run-up measured was at 12.5 m (41 ft) with inundation distance of 390 m to 1.5 km (0.242–0.932 miles) in Yala. In Hambantota,

tsunami run-ups measured 11 m (36.1 ft) with the greatest inundation

distance of 2 km (1.24 miles). Tsunami run-up measurements along the Sri

Lankan coasts are at 2.4–11 m (7.87–36.1 ft). Tsunami waves measured on the east coast ranged from 4.5–9 m (14.8–29.5 ft) at Pottuvill to Batticaloa at 2.6–5 m (8.53–16.4 ft) in the northeast around Trincomalee and 4–5 m (13.1–16.4 ft) in the west coast from Moratuwa to Ambalangoda.

Sri Lanka tsunami height survey:

- 9 m (29.5 ft) at Koggala

- 6 m (19.7 ft) at Galle port

- 4.8 m (15.7 ft) around the Galle coast

- 8.7 m (28.6 ft) at Nonagama

- 4.9 m (16.1 ft) at Weligama

- 4 m (13.1 ft) at Dodundawa

- 4.7 m (15.4 ft) at Ambalangoda

- 4.7 m (15.4 ft) at Hikkaduwa Fishery Harbour

- 10 m (33 ft) at Kahawa

- 4.8 m (15.7 ft) at North Beach of Beruwala

- 6 m (19.7 ft) at Paiyagala

A regular passenger train operating between Maradana and Matara was derailed and overturned by the tsunami and claimed at least 1,700 lives, the largest single rail disaster death toll in history.

Estimates based on the state of the shoreline and a high-water mark on a

nearby building place the tsunami 7.5–9 m (24.6 ft to 29.5 ft) above

sea level and 2–3 m (6.6 ft to 9.8 ft) higher than the top of the train.

In Sri Lanka, the civilian casualties were second only to those

in Indonesia. The eastern shores of Sri Lanka were hardest hit since

they face the epicenter of the earthquake. The southwestern shores were

hit later, but the death toll was just as severe. The southwestern

shores are a hotspot for tourists and fishing.

The degradation of the natural environment in Sri Lanka contributed to

the high death tolls. Approximately 90,000 buildings, many wooden

houses, were destroyed.

Thailand

The tsunami hit the southwest coast of southern Thailand,

which was about 500 km (310.69 miles) from the epicenter. The region is

heavily visited by foreigners during the Christmas season. Since the

tsunami hit during high tide, its damage was severe. Approximately 5,400

people were killed and 3,100 people were reported missing. The places

where the tsunami struck were Phang Nga Province, Phuket, the Phi Phi Islands, Ko Racha Yai, Ko Lanta Yai and Ao Nang of Krabi Province, offshore archipelagos like the Surin Islands, the Similan Islands, and coastal areas of Satun, Ranong, and Trang.

Thailand experienced the largest tsunami run-up height outside of Sumatra, at Khao Lak and Takua Pa District that face the Andaman Sea. The tsunami heights recorded:

Thai Navy boat stranded almost 2 km inland

- 6–10 m (19.7–32.8 ft) in Khao Lak

- 3–6 m (9.8–19.7 ft) along the west coast of Phuket island

- 3 m (9.8 ft) along the south coast of Phuket island

- 2 m (6.6 ft) along the east coast of Phuket island

- 4–6 m (13.1–19.7 ft) on the Phi Phi Islands

- 19.6 m (64.3 ft) at Ban Thung Dap

- 5 m (16.4 ft) at Ramson

- 6.8 m (22.3 ft) at Ban Thale Nok

- 5 m (16.4 ft) at Hat Praphat (Ranong Coastal Resources Research Station)

- 6.3 m (20.7 ft) at Thai Mueang District

- 6.8 m (22.3 ft) at Rai Dan

The province of Phang Nga was the most affected area in Thailand. The

northern part of Phang Nga Province is rural, with fishery and

agricultural villages while the central part has several resort hotels.

Khao Lak is in the south of Phang Nga Province with many luxury hotels,

popular with foreign tourists. Khao Lak was hit by the tsunami after

10:00 and had the largest death toll in Thailand.

A maximum inundation of approximately 2 km (1.2 miles) and the

inundated depths were 4–7 m (13–23 ft) in Khao Lak, inundating the third

floor of a resort hotel. Tsunami heights in Khao Lak were much higher

than on Phuket Island. The reason for the difference seems to have been

caused by the local bathymetry

off Khao Lak. According to interviews, the leading wave produced an

initial depression, called a tsunami drawback or "disappearing sea"

effect and the second wave was larger.

Tsunami wave striking the Phuket coast

The highest recorded tsunami run-up measured 19.6 m (64.3 ft) at Ban Thung Dap, on the southwest tip of Ko Phra Thong Island and the second highest at 15.8 m (51.8 ft) at Ban Nam Kim.

At Phuket island, many west coast beaches were affected. At Patong Beach,

a tourist mecca, tsunami heights were 5–6 m (16.4–19.7 ft) and the

inundated depth was about 2 m (6.6 ft). Tsunami heights became lower

from the west coast, the south coast to the east coast of the island. On

Karon Beach on the west coast, the coastal road was built higher than

the shore, protecting a hotel which was behind it. On the east coast of

Phuket Island, the tsunami height was about 2 m (6.6 ft). In one river

mouth, many boats were damaged. The tsunami moved counter-clockwise

around Phuket Island, as was the case at Okushiri Island in the 1993 Hokkaido earthquake. According to interviews, the leading wave produced an initial depression and the second wave was the largest.

The Phi Phi Islands

are a group of small islands that were affected by the tsunami. The

north bay of Phi Phi Don Island opens to the northwest in the direction

of the tsunami. The measured tsunami height on this beach was 5.8 m

(19.0 ft). According to some eyewitness accounts, the tsunami came from

the north and south. The ground level was about 2 m (6.6 ft) above sea

level and there were many cottages and hotels. The south bay opens to

the southeast and faces in the opposite direction from the tsunami.

Further, Phi Phi Le Island shields the port of Phi Phi Don Island. The

measured tsunami height was 4.6 m (15.1 ft) in the port.

India

The tsunami arrived in the states of Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu along the southeast coast of the Indian mainland shortly after 9:00 a.m. At least two hours later, it arrived in the state of Kerala along the southwest coast. Tamil Nadu, the union territory of Pondicherry

and Kerala were extensively damaged, while Andhra Pradesh sustained

moderate damage. There were two to five waves of varying height that

coincided with the local high tide in some areas.

The tsunami run-up was only 1.6 m (5.2 ft) in areas in the state

of Tamil Nadu shielded by the island of Sri Lanka, but was 4–5 m

(13.1–16.4 ft) in coastal districts such as Nagapattinam in Tamil Nadu directly across from Sumatra. On the western coast, the runup elevations were 4.5 m (14.8 ft) at Kanyakumari District in Tamil Nadu, and 3.4 m (11.2 ft) each at Kollam and Ernakulam Districts in Kerala. The time between the waves varied from about 15 minutes to 90 minutes. The tsunami varied in height from 2–10 m (6.6–33 ft) based on survivor's accounts.

Destruction in Chennai

The tsunami runup height measured in mainland India by Ministry of Home Affairs includes:

- 3.4 m (11.2 ft) at Kerala, inundation distance of 0.5–1.5 km (0.31–0.62 miles) with 250 km (155.3 miles) of coastline affected

- 4.5 m (14.8 ft) at southern coastline of Tamil Nadu, inundation distance of 0.2–2.0 km (0.12–1.24 miles) with 100 km (62.1 miles) of coast affected

- 5 m (16.4 ft) at eastern coastline of Tamil Nadu facing tsunami source, inundation distance of 0.4–1.5 km (0.25–0.93 miles) with 800 km (497 miles) of coastline affected

- 4 m (13.1 ft) at Pondicherry, inundation distance of 0.2–2.0 km (0.12–1.24 miles) with 25 km (15.5 miles) of coast affected

- 2.2 m (7.22 ft) at Andhra Pradesh, inundation distance of 0.2–1.0 km (0.12–0.62 miles) with 985 km (612 miles) of coast

The tsunami traveled 2.5 km (1.55 miles) at its maximum inland at Karaikal, Puducherry. The inundation

distance varied between 100–500 m (0.062 miles-0.311 miles) in most

areas, except at river mouths, where it was more than 1 km (0.62 miles).

Areas with dense coconut groves or mangroves had much smaller

inundation distances, and those with river mouths or backwaters saw

larger inundation distances.

Presence of seawalls at the Kerala and Tamil Nadu coasts reduced the

impact of the waves. However, when the seawalls were made of loose

stones, the stones were displaced and carried a few metres inland.

The state of Kerala experienced tsunami-related damage in three southern densely populated districts, Ernakulam, Alappuzha, and Kollam, due to diffraction of the waves around Sri Lanka. The southernmost district of Thiruvananthpuram,

however, escaped damage, possibly due to the wide turn of the

diffracted waves at the peninsular tip. Major damage occurred in two

narrow strips of land bound on the west by the Arabian Sea and on the east by the Kerala backwaters.

The waves receded before the first tsunami with the highest fatality

reported from the densely populated Alappad panchayat (including the

villages of Cheriya Azhikkal and Azhikkal) at Kollam district, caused by

a 4 m (13.1 ft) tsunami.

The worst affected area in Tamil Nadu was Nagapattinam district, with 6,051 fatalities reported by a 5 m (16.4 ft) tsunami, followed by Cuddalore district, with many villages destroyed. The 13 km (8.1 miles) Marina Beach in Chennai

was battered by the tsunami which swept across the beach taking morning

walkers unaware. Besides that, a 10 m (33 ft) black muddy tsunami

ravaged the city of Karaikal, where 492 lives were lost. The city of

Pondicherry, protected by seawalls was relatively unscathed.

Many villages in the state of Andhra Pradesh were destroyed. In

the Krishna district, the tsunami created havoc in Manginapudi and on

Machalipattanam Beach. The most affected was Prakasham District,

recording 35 deaths, with maximum damage at Singraikonda.

Given the enormous power of the tsunami, the fishing industry suffered

the greatest. Moreover, the cost of damage in the transport sector was

reported in the tens of thousands.

The tsunami effects varied greatly across different coastal areas

according to the number of waves experienced, the inundation distance

and height of waves, and the population density of the area, and

topological and geographical features. Besides these factors, the number

of lives lost was influenced by exposure to previous disasters and the

local disaster management capability. Most of the people killed were

members of the fishing community.

The tsunami arrived in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands

minutes after the earthquake causing extensive devastation to the

islands' environment. Specifically, the Andaman Islands were moderately

affected while the island of Little Andaman and the Nicobar Islands were

severely affected by the tsunami. The tsunami survey was carried out in

Little Andaman, South Andaman, mainly in and around Port Blair, Car

Nicobar along the Kankana-Mus sector, and Great Nicobar.

In South Andaman, based on local eyewitnesses, there were three

tsunami waves. Of the three, the third was the most devastating.

Flooding occurred at the coastlines of the islands and low-lying areas

inland, connected to open sea through creeks. Inundation was observed,

along east coast of South Andaman Island, restricted to Chidiyatapu,

Burmanallah, Kodiaghat, Beadnabad, Corbyn's cove and Marina

Park/Aberdeen Jetty areas. Along the west coast, the inundation was

observed around Guptapara, Manjeri, Wandoor, Collinpur and Tirur

regions. Several near shore establishments and numerous infrastructures

such as seawalls and a 20 MW diesel generated power plant at Bamboo Flat

were extensively damaged.

Results of the tsunami survey in South Andaman along Chiriyatapu, Corbyn's Cove and Wandoor beaches:

- 5.0 m (16.4 ft) in maximum tsunami height with a run-up of 4.24 m (13.9 ft) at Chiriyatapu Beach

- 5.5 m (18 ft) in maximum tsunami height and run-up at Corbyn's Cove Beach

- 6.6 m (21.8 ft) in maximum tsunami height and run-up of 4.63 m (15.2 ft) at Wandoor Beach

Meanwhile, in the Little Andaman, tsunami waves impinged on the

eastern shore of this island 25 to 30 minutes after the earthquake in a

four-wave cycle of which the fourth one was most devastating with a wave

height of about 10 m (33 ft). The tsunami water destroyed settlements

at Hut Bay within a range of 1 km from the seashore. Run up level up to

3.3 m (10.8 ft) have been measured.

In Malacca located on the island of Car Nicobar, there were three

tsunami waves. The first wave came 5 minutes after the earthquake,

preceded by recession of the seawater up to 600–700 m (1969–2297 ft).

The second and third waves came in 10 minutes intervals after the first

wave. The third wave was the strongest, with a maximum tsunami wave

height of 11 m (36 ft). Waves nearly 3 stories high devastated the

Indian Air Force base, located just south of Malacca. The maximum

tsunami wave height of 11 m (36 ft).

Inundation limit was found to be up to 1.25 km (4101 ft) inland. The

impact of the waves was so severe that four Oil tankers of IOC were

thrown almost 800 m (2624 ft) from the seashore near Malacca to Air

force colony main gate. In Chuckchucha and Lapati, the tsunami arrived in a three wave cycle with a maximum tsunami wave height of 12 m (39 ft).

In Campbell Bay of Great Nicobar island, the tsunami waves hit

the area three times with an inundation limit of 250–550 m

(820–1804 ft). The first wave came within 5 minutes of the earthquake.

The second and third waves came 10 minute intervals after first. The

second wave was the strongest. Deadly tsunami waves wreaked havoc in

this densely populated Jogindar Nagar area, situated 13 km south of

Campbell Bay. According to local information,

tsunami waves attacked the area three times. The first wave came 5

minutes after the main shock (0629 hrs.) with a marginal drop in sea

level. The second wave came 10 minutes after the first one with a

maximum height of 4.8 m (15.9 ft) and caused the major destruction. The

third wave came within 15 minutes after the second with a lower wave

height. The maximum inundation limit due to tsunami water was about 500 m

(0.5 km).

The worst affected island in the Andaman & Nicobar chain is

Katchall Island with 303 people confirmed dead and 4,354 missing out of a

total population of 5,312.

At Port Blair

the water receded before the first wave, and the third wave was the

tallest and caused the most damage. However, at Hut Bay, Malacca and Campbell Bay—locations

south of Port Blair—the water level rose by about 1–2 m (3.3–6.6 ft)

from the normal sea level before the first wave crashed ashore.

Reports of tsunami wave height:

- 1.5 m (4.9 ft) at Diglipur and Rangat at North Andaman Island

- 8 m (26.2 ft) high at Campbell Bay on Great Nicobar Island

- 10–12 m (32.8–39.4 ft) high at Malacca (in Car Nicobar Island) and at Hut Bay on Little Andaman Island

- 3 m (9.8 ft) high at Port Blair on South Andaman Island

The significant shielding of Port Blair and Campbell Bay by steep

mountainous outcrops contributed to the relatively low wave heights at

these locations, whereas the open terrain along the eastern coast at

Malacca and Hut Bay contributed to the great height of the tsunami waves.

Maldives

The tsunami severely affected the Maldives

at a distance of 2,500 km (1553.4 miles) from the epicenter.

Identically to Sri Lanka, survivors reported three waves with the second

wave being the most powerful. Being rich in coral reefs, the Maldives

provides an opportunity for scientists to assess the impact of a tsunami

on coral atolls. The significantly lower tsunami impact on the Maldives

compared to Sri Lanka is largely due to the topography and bathymetry

of the atoll chain with offshore coral reefs, deep channels separating

individual atolls and its arrival within low tide which decreased the

power of the tsunami. After the tsunami, there were some concern that

the country might be totally submerged and become uninhabitable.

However, this was proven untrue.

The largest tsunami wave measured was 4 m (13.1 ft) at Vilufushi Island

(Thaa Atoll). The tsunami arrived approximately 2 hours after the

earthquake. The greatest tsunami inundation occurred at North Male

Atoll, Male island at 250 m (0.155 miles) along the streets.

The Maldives tsunami wave analysis:

- 1.3–2.4 m (4.27–7.87 ft) at North Male Atoll, Male Island

- 2 m (6.56 ft) at North Male Atoll, Huhule Island

- 1.7–2.8 m (5.58–9.2 ft) at South Male Atoll, Embudhu Finothu

- 2.5–3.3 m (8.2–10.8 ft) at Laamu Atoll, Fonadhoo Island

- 2.2–2.9 m (7.2–9.51 ft) at Laamu Atoll, Gan Island

- 2.3–3.0 m (7.5–9.8 ft) at North Male Atoll, Dhiffushi Island

- 2.2–2.4 m (7.2–7.87 ft) at North Male Atoll, Huraa Island

- more than 1.5 m (4.92 ft) at North Male Atoll, Kuda Huraa Island

Myanmar

In Myanmar,

the tsunami caused only moderate damage, which arrived between 2 and

5.5 hours after the earthquake. Although the country's western Andaman Sea

coastline lies at the proximity of the rupture zone, there were smaller

tsunamis than the neighboring Thai coast, probably because the main

tsunami source did not extend to the Andaman Islands. Another factor is

that some coasts of Taninthayi Division was protected by offshore islands of the Myeik Archipelago.

Based on scientific surveys from Ayeyarwaddy Delta through Taninthayi

Division, it is revealed that tsunami heights along the Myanmar coast

were between 0.4–2.9 m (1.3–9.5 ft). Eyewitnesses often compared the

December tsunami heights with the "rainy season high tide"; although at

most locations, the tsunami height was similar or smaller than the

"rainy season high tide" level.

Tsunami survey heights:

- 0.6–2.3 m (1.97–7.54 ft) around the Ayeyarwady delta

- 0.9–2.9 m (2.95–9.5 ft) at Dawei area

- 0.7–2.2 m (2.3–7.2 ft) around Myeik

- 0.4–2.6 m (1.3–8.5 ft) around Kawthaung

Interviews with local people indicate that they did not feel the earthquake in Taninthayi Division

or in Ayeyarwaddy Delta. The 71 casualties can be attributed to poor

housing infrastructure and additionally, the fact that the coastal

residents in the surveyed areas live on flat land along the coast,

especially in the Ayeyarwaddy Delta, and that there is no higher ground

to evacuate to. The tsunami heights from the 2004 December earthquake

were not more than 3 m (9.8 ft) along the Myanmar coast, the amplitudes

are slightly large off the Ayeyarwaddy Delta, probably because the

shallow delta cause a concentration in tsunami energy.

Somalia

The tsunami travelled 5000 km (3106.86 miles) west across the open ocean before striking the East African country of Somalia. Around 289 fatalities were reported in the Horn of Africa, drowned by four tsunami waves. The hardest hit was a 650 km (403.9 miles) stretch of the Somalia coastline between Garacad (Mudug region) and Xaafuun (Bari region), which forms part of the Puntland Province. Most of the victims were reported along the low-lying Xaafuun Peninsula.

The Puntland coast in northern Somalia was by far the area hardest hit

by the waves to the west of the Indian subcontinent. The waves arrived

around noon local time.

Consequently, tsunami runup heights vary from 5 m (16.4 ft) to

9 m (29.5 ft) with inundation distances varying from 44 m (0.027 miles)

to 704 m (0.44 miles). The maximum runup height of almost 9 m (29.5 ft)

was recorded in Bandarbeyla. An even higher runup point was measured on a

cliff near the town of Eyl, solely on an eyewitness account.

The highest death toll was in Xaafuun, also known as Hafun,

with 19 bodies and 160 people presumed missing out of its 5000

inhabitants, which amounts to the highest number of casualties in a

single African town and the largest tsunami death toll in a single town

to the west of the Indian subcontinent. In Xaafuun, small drawbacks were observed before the third and most powerful tsunami flood the town.

Other locations

Flooding in George Town, Malaysia

The tsunami also reached Malaysia, mainly on the northern states such as Kedah, Perak and Penang and on offshore islands such as Langkawi island. Peninsular Malaysia

was shielded by the full force of the tsunami due to the protection

offered by the island of Sumatra, which lies just off the western coast.

Bangladesh escaped major damage and deaths because the water displaced by the strike-slip fault was relatively little on the northern section of the rupture zone, which ruptured slowly. In Yemen, the tsunami killed 2 people with a maximum runup of 2 m (6.6 ft).

The tsunami was detected in the southern parts of east Africa,

where rough seas were reported, specifically on the eastern and southern

coasts that face the Indian Ocean. A few other African countries also

recorded fatalities; one in Kenya, three in Seychelles, ten in Tanzania, and South Africa, where two were killed as a direct result of tsunami—the furthest from the epicentre.

Tidal surges also occurred along the Western Australian coast that lasted for several hours, resulting in boats losing their moorings and two people needing to be rescued.

Impact

Countries affected

Countries affected

According to the U.S. Geological Survey a total of 227,898 people died. Measured in lives lost, this is one of the ten worst earthquakes in recorded history,

as well as the single worst tsunami in history. Indonesia was the worst

affected area, with most death toll estimates at around 170,000. In an initial report by Siti Fadilah Supari,

the Indonesian Minister of Health at the time, estimated the death

total to be as high as 220,000 in Indonesia alone, giving a total of

280,000 fatalities. However, the estimated number of dead and missing in Indonesia were later reduced by over 50,000. In their report, the Tsunami Evaluation Coalition

stated, "It should be remembered that all such data are subject to

error, as data on missing persons especially are not always as good as

one might wish". A much higher number of deaths has been suggested for Myanmar based on reports from Thailand.

The tsunami caused serious damage and deaths as far as the east

coast of Africa, with the furthest recorded fatality directly attributed

to the tsunami at Rooi-Els, close to Cape Town, 8,000 km (5,000 mi) from the epicenter. In total, eight people in South Africa died due to high sea levels and waves.

Relief agencies reported that one-third of the dead appeared to

be children. This was a result of the high proportion of children in the

populations of many of the affected regions and because children were

the least able to resist being overcome by the surging waters. Oxfam

went on to report that as many as four times more women than men were

killed in some regions because they were waiting on the beach for the

fishermen to return and looking after their children in the houses.

States of emergency were declared in Sri Lanka, Indonesia, and

the Maldives. The United Nations estimated at the outset that the relief

operation would be the costliest in human history. Then-UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan

stated that reconstruction would probably take between five and ten

years. Governments and non-governmental organizations feared that the

final death toll might double as a result of diseases, prompting a

massive humanitarian response.

In addition to a large number of local residents, up to

9,000 foreign tourists (mostly Europeans) enjoying the peak holiday

travel season were among the dead or missing, especially people from the

Nordic countries. The European nation hardest hit was Sweden, with a death toll of 543. Germany was close behind with 539 identified victims.

Economic impact

Chennai's Marina Beach after the tsunami

The level of damage to the economy resulting from the tsunami depends

on the scale examined. While local economies were devastated, the

overall impact to the national economies was minor. The two main

occupations affected by the tsunami were fishing and tourism.

The impact on coastal fishing communities and the people living there,

some of the poorest in the region, has been devastating with high losses

of income earners as well as boats and fishing gear.

In Sri Lanka artisanal fishery, where the use of fish baskets, fishing

traps, and spears are commonly used, is an important source of fish for

local markets; industrial fishery is the major economic activity,

providing direct employment to about 250,000 people. In recent years the

fishery industry has emerged as a dynamic export-oriented sector,

generating substantial foreign exchange earnings. Preliminary estimates

indicate that 66% of the fishing fleet and industrial infrastructure in

coastal regions have been destroyed by the wave surges, which will have

adverse economic effects both at local and national levels.

While the tsunami destroyed many of the boats vital to Sri

Lanka's fishing industry, it also created demand for fiberglass

reinforced plastic catamarans in boatyards of Tamil Nadu.

Since over 51,000 vessels were lost to the tsunami, the industry

boomed. However, the huge demand has led to lower quality in the

process, and some important materials were sacrificed to cut prices for

those who were impoverished by the tsunami.

Some economists believe that damage to the affected national

economies will be minor because losses in the tourism and fishing

industries are a relatively small percentage of the GDP. However, others

caution that damage to infrastructure is an overriding factor. In some

areas drinking water supplies and farm fields may have been contaminated

for years by salt water from the ocean.

Even though only coastal regions were directly affected by the waters

of the tsunami, the indirect effects have spread to inland provinces as

well. Since the media coverage of the event was so extensive, many

tourists cancelled vacations and trips to that part of the world, even

though their travel destinations may not have been affected. This ripple

effect could especially be felt in the inland provinces of Thailand,

such as Krabi, which acted like a starting point for many other tourist

destinations in Thailand.

Both the earthquake and the tsunami may have affected shipping in the Malacca Straits,

which separate Malaysia and the Indonesian island of Sumatra, by

changing the depth of the seabed and by disturbing navigational buoys

and old shipwrecks. In one area of the Strait, water depths were

previously up to 4,000 feet (1,200 m), and are now only 100 feet (30 m)

in some areas, making shipping impossible and dangerous. These problems

also made the delivery of relief aid more challenging. Compiling new

navigational charts may take months or years. However, officials hope

that piracy in the region will drop off as a result of the tsunami.

Countries in the region appealed to tourists to return, pointing

out that most tourist infrastructure is undamaged. However, tourists

were reluctant to do so for psychological reasons. Even beach resorts in

parts of Thailand which were untouched by the tsunami were hit by

cancellations.

Environmental impact

Tsunami inundation in Khao Lak, Thailand

Beyond the heavy toll on human lives, the Indian Ocean earthquake has

caused an enormous environmental impact that will affect the region for

many years to come. It has been reported that severe damage has been

inflicted on ecosystems such as mangroves, coral reefs, forests, coastal wetlands, vegetation, sand dunes and rock formations, animal and plant biodiversity and groundwater. In addition, the spread of solid and liquid waste and industrial chemicals, water pollution and the destruction of sewage

collectors and treatment plants threaten the environment even further,

in untold ways. The environmental impact will take a long time and

significant resources to assess.

According to specialists, the main effect is being caused by

poisoning of the freshwater supplies and of the soil by saltwater

infiltration and a deposit of a salt layer over arable land. It has been

reported that in the Maldives, 16 to 17 coral reef atolls that were

overcome by sea waves are without fresh water and could be rendered

uninhabitable for decades. Uncountable wells that served communities

were invaded by sea, sand, and earth; and aquifers

were invaded through porous rock. Salted-over soil becomes sterile, and

it is difficult and costly to restore for agriculture. It also causes

the death of plants and important soil micro-organisms. Thousands of

rice, mango, and banana plantations in Sri Lanka were destroyed almost

entirely and will take years to recover. On the island's east coast, the

tsunami contaminated wells on which many villagers relied for drinking

water. The Colombo-based International Water Management Institute

monitored the effects of saltwater and concluded that the wells

recovered to pre-tsunami drinking water quality one and a half years

after the event. IWMI developed protocols for cleaning wells contaminated by saltwater; these were subsequently officially endorsed by the World Health Organization as part of its series of Emergency Guidelines.

The United Nations Environment Programme

(UNEP) is working with governments of the region in order to determine

the severity of the ecological impact and how to address it.

UNEP has decided to earmark a US$1,000,000 emergency fund and to

establish a Task Force to respond to requests for technical assistance

from countries affected by the tsunami. In response to a request from the Maldivian Government,

the Australian Government sent ecological experts to help restore

marine environments and coral reefs—the lifeblood of Maldivian tourism.

Much of the ecological expertise has been rendered from work with the Great Barrier Reef, in Australia's northeastern waters.

Historical context

Of the ten strongest Indonesian earthquakes ≥ 8.3 Mw, six occurred near Sumatra

The last major tsunami in the Indian Ocean was about A.D. 1400.

In 2008, a team of scientists working on Phra Thong, a barrier island

along the hard-hit west coast of Thailand, reported evidence of at least

three previous major tsunamis in the preceding 2,800 years, the most

recent from about 700 years ago. A second team found similar evidence of

previous tsunamis in Aceh, a province at the northern tip of Sumatra;

radiocarbon dating of bark fragments in soil below the second sand

layer led the scientists to estimate that the most recent predecessor to

the 2004 tsunami probably occurred between A.D. 1300 and 1450.

The 2004 earthquake and tsunami combined is the world's deadliest natural disaster since the 1976 Tangshan earthquake. The earthquake was the third most powerful earthquake recorded since 1900. The deadliest known earthquake in history occurred in 1556 in Shaanxi, China, with an estimated death toll of 830,000, though figures from this period may not be as reliable.

Before 2004, the tsunami created in both Indian and Pacific Ocean waters by the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa,

thought to have resulted in anywhere from 36,000 to 120,000 deaths, had

probably been the deadliest in the region. In 1782 about 40,000 people

are thought to have been killed by a tsunami (or a cyclone) in the South China Sea. The most deadly tsunami before 2004 was Italy's 1908 Messina earthquake on the Mediterranean Sea where the earthquake and tsunami killed about 123,000.

Other effects

Tsunami aftermath in Aceh, Indonesia

Many health professionals and aid workers have reported widespread

psychological trauma associated with the tsunami. Traditional beliefs in

many of the affected regions state that a relative of the family must

bury the body of the dead, and in many cases, no body remained to be

buried. Women in Aceh required a special approach from foreign aid

agencies, and continue to have unique needs.

The hardest hit area, Aceh, is a religiously conservative Islamic society and has had no tourism nor any Western presence in recent years due to the Insurgency in Aceh between the Indonesian military and Free Aceh Movement.

Some believe that the tsunami was divine punishment for lay Muslims

shirking their daily prayers and/or following a materialistic lifestyle.

Others have said that Allah was angry that there were Muslims killing

other Muslims in an ongoing conflict. Saudi cleric Muhammad Al-Munajjid

attributed it to divine retribution against non-Muslim vacationers "who

used to sprawl all over the beaches and in pubs overflowing with wine"

during Christmas break.

The widespread devastation caused by the tsunami led the Free

Aceh Movement to declare a cease-fire on 28 December 2004 followed by

the Indonesian government, and the two groups resumed long-stalled peace

talks, which resulted in a peace agreement signed 15 August 2005. The

agreement explicitly cites the tsunami as a justification.

In a poll conducted in 27 countries, 15 percent of respondents

named the tsunami the most significant event of the year. Only the Iraq War was named by as many respondents.

The extensive international media coverage of the tsunami, and the role

of mass media and journalists in reconstruction, were discussed by

editors of newspapers and broadcast media in tsunami-affected areas, in

special video-conferences set up by the Asia Pacific Journalism Centre.

The tsunami left both the people and government of India in a

state of heightened alert. On 30 December 2004, four days after the

tsunami, Terra Research notified the India government that its sensors

indicated there was a possibility of 7.9 to 8.1 magnitude tectonic shift

in the next 12 hours between[Sumatra and New Zealand. In response, the Indian Minister of Home Affairs announced that a fresh onslaught of deadly tsunami were likely along the India southern coast and Andaman and Nicobar Islands, even as there was no sign of turbulence in the region.

The announcement generated panic in the Indian Ocean region and caused

thousands to flee their homes, which resulted in jammed roads. The announcement was a false alarm and the Home Affairs minister withdrew their announcement.

On further investigation, the India government learned that the

consulting company Terra Research was run from the home of a

self-described earthquake forecaster who had no telephone listing and maintained a website where he sold copies of his detection system.

Patong Beach in Thailand after the tsunami

The tsunami had a severe humanitarian and political impact in Sweden.

The hardest hit country outside Asia, Sweden, lost 543 tourists, mainly

in Thailand. The Persson Cabinet was heavily criticized for its inaction.

Smith Dharmasaroja, a meteorologist who had predicted that an earthquake and tsunami "is going to occur for sure" way back in 1994,

was assigned the development of the Thai tsunami warning system. The

Indian Ocean Tsunami warning system was formed in early 2005 to provide

an early warning of tsunamis for inhabitants around the Indian Ocean

coasts.

The changes in the distribution of masses inside the Earth due to the earthquake had several consequences. It displaced the North Pole

by 2.5 cm. It also slightly changed the shape of the Earth,

specifically by decreasing Earth's oblateness by about one part in 10

billion, consequentially increasing Earth's rotation a little and thus shortening the length of the day by 2.68 microseconds.

Humanitarian response

German tsunami relief mission visiting Mullaitivu in Sri Lanka's Northern Province

A great deal of humanitarian aid

was needed because of widespread damage of the infrastructure,

shortages of food and water, and economic damage. Epidemics were of

special concern due to the high population density and tropical climate

of the affected areas. The main concern of humanitarian and government

agencies was to provide sanitation facilities and fresh drinking water

to contain the spread of diseases such as cholera, diphtheria, dysentery, typhoid and hepatitis A and hepatitis B.

There was also a great concern that the death toll could increase

as disease and hunger spread. However, because of the initial quick

response, this was minimized.

In the days following the tsunami, significant effort was spent

in burying bodies hurriedly due to fear of disease spreading. However,

the public health risks may have been exaggerated, and therefore this

may not have been the best way to allocate resources. The World Food Programme provided food aid to more than 1.3 million people affected by the tsunami.

Nations all over the world provided over US$14 billion in aid for damaged regions,

with the governments of Australia pledging US$819.9 million (including a

US$760.6-million aid package for Indonesia), Germany offering US$660

million, Japan offering US$500 million, Canada offering US$343 million,

Norway and the Netherlands offering both US$183 million, the United

States offering US$35 million initially (increased to US$350 million),

and the World Bank

offering US$250 million. Also Italy offered US$95 million, increased

later to US$113 million of which US$42 million was donated by the

population using the SMS system.

Memorial dedicated to victims of the tsunami, Batticaloa, eastern Sri Lanka

According to USAID,

the US has pledged additional funds in long-term U.S. support to help

the tsunami victims rebuild their lives. On 9 February 2005, President

Bush asked Congress to increase the U.S. commitment to a total of US$950

million. Officials estimated that billions of dollars would be needed.

Bush also asked his father, former President George H. W. Bush, and

former President Bill Clinton to lead a U.S. effort to provide private

aid to the tsunami victims.

In mid-March the Asian Development Bank

reported that over US$4 billion in aid promised by governments was

behind schedule. Sri Lanka reported that it had received no foreign

government aid, while foreign individuals had been generous.

Many charities were given considerable donations from the public. For

example, in the United Kingdom the public donated roughly £330,000,000

sterling (nearly US$600,000,000). This considerably outweighed the

allocation by the government to disaster relief and reconstruction of

£75,000,000, and came to an average of about £5.50 (US$10) donated by

every citizen.

In August 2006, fifteen local aid staff working on post-tsunami

rebuilding were found executed in northeast Sri Lanka after heavy

fighting, the main umbrella body for aid agencies in the country said.

In popular culture

Film and television

- Children of Tsunami: No More Tears (2005), a 24-minute documentary

- The Wave That Shook The World (2005), educational television-series documentary about the tsunami

- Tsunami: The Aftermath (2006), a two-part television miniseries about its aftermath

- Hereafter (2010), a main character's life is affected after surviving the tsunami while on vacation

- Hafalan Shalat Delisa (2011), an Indonesian movie

- The Impossible (2012), an English-language Spanish film based on the story of María Belón and her family

- Kayal (2014), a Tamil drama film which culminates with the tsunami

Literature

- The Killing Sea (2006), two teenagers struggle to survive in the days after the tsunami

- Wave (2013), a memoir by Sonali Deraniyagala

Music

- "12/26" by Kimya Dawson, about the event and the humanitarian efforts, from the perspective of a victim whose family died in the disaster